Paris Commune Posters

January 30, 2013

Description by Drew Flanagan, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in history

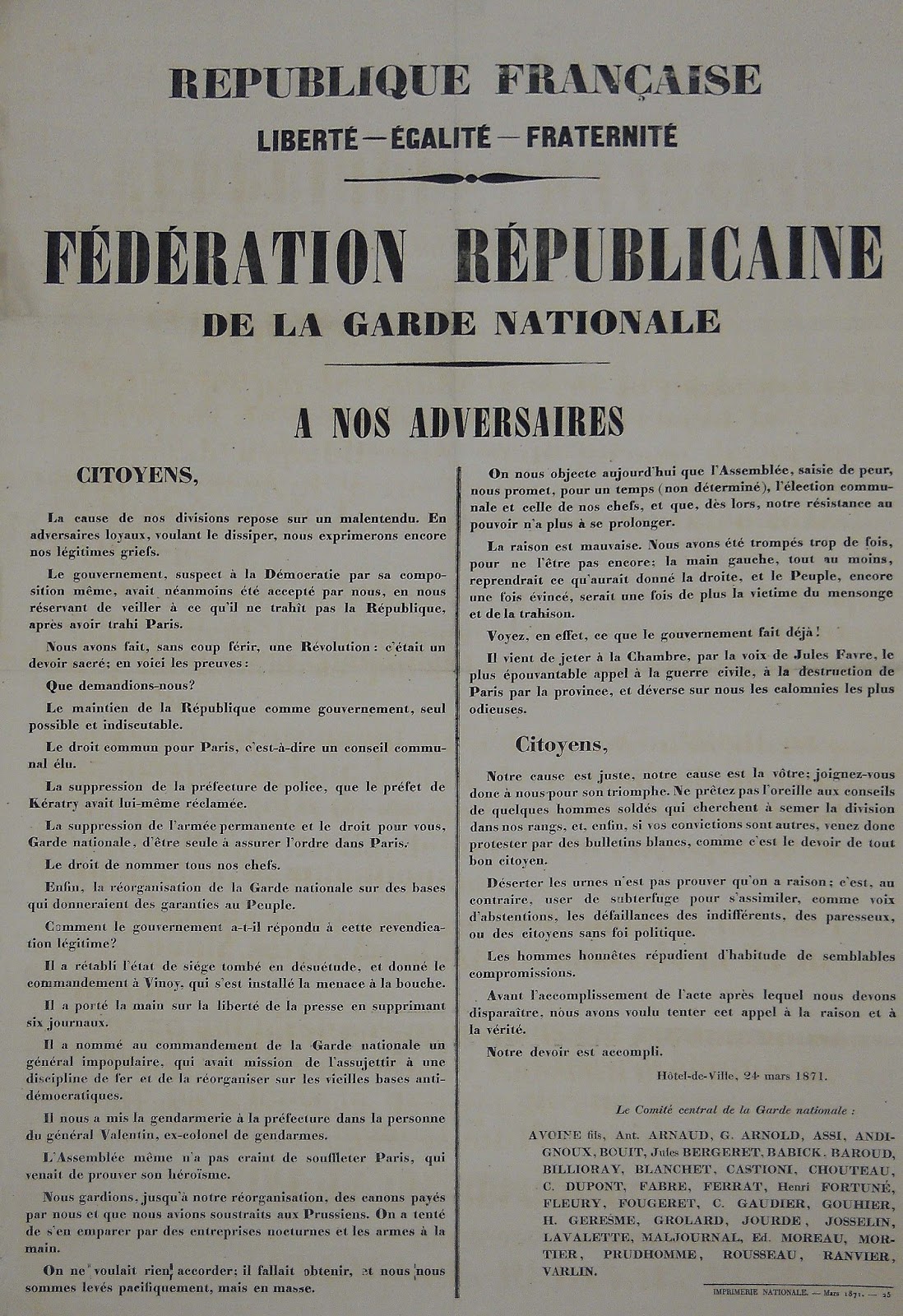

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department has seven posters that were displayed publicly during the events of the 1871 Paris Commune. The collection includes posters published on behalf of both the government at Versailles and the Communards. The posters contain orders and communiqués as well as information and propaganda relating to the military and political events of the uprising.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department has seven posters that were displayed publicly during the events of the 1871 Paris Commune. The collection includes posters published on behalf of both the government at Versailles and the Communards. The posters contain orders and communiqués as well as information and propaganda relating to the military and political events of the uprising.

In September of 1870, Emperor Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (known as Napoleon III) and Marshal Patrice MacMahon led the French army into battle at Sedan. In a day of desperate and bloody fighting, the French forces were badly beaten by a German army led by Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke and Prussian King Wilhelm I. The Germans took many prisoners, most notably the emperor himself, and French Republicans seized the opportunity to depose Louis Napoleon and to bring an end to the Second French Empire. A new republic was declared at Versailles, committed (at least at first) to carrying on the war. German forces occupied a significant proportion of French territory, including the contested border region of Alsace-Lorraine, and laid siege to Paris. The "Government of National Defense" at Versailles soon realized the hopelessness of its situation and renewed armistice talks with the newly declared German Empire.

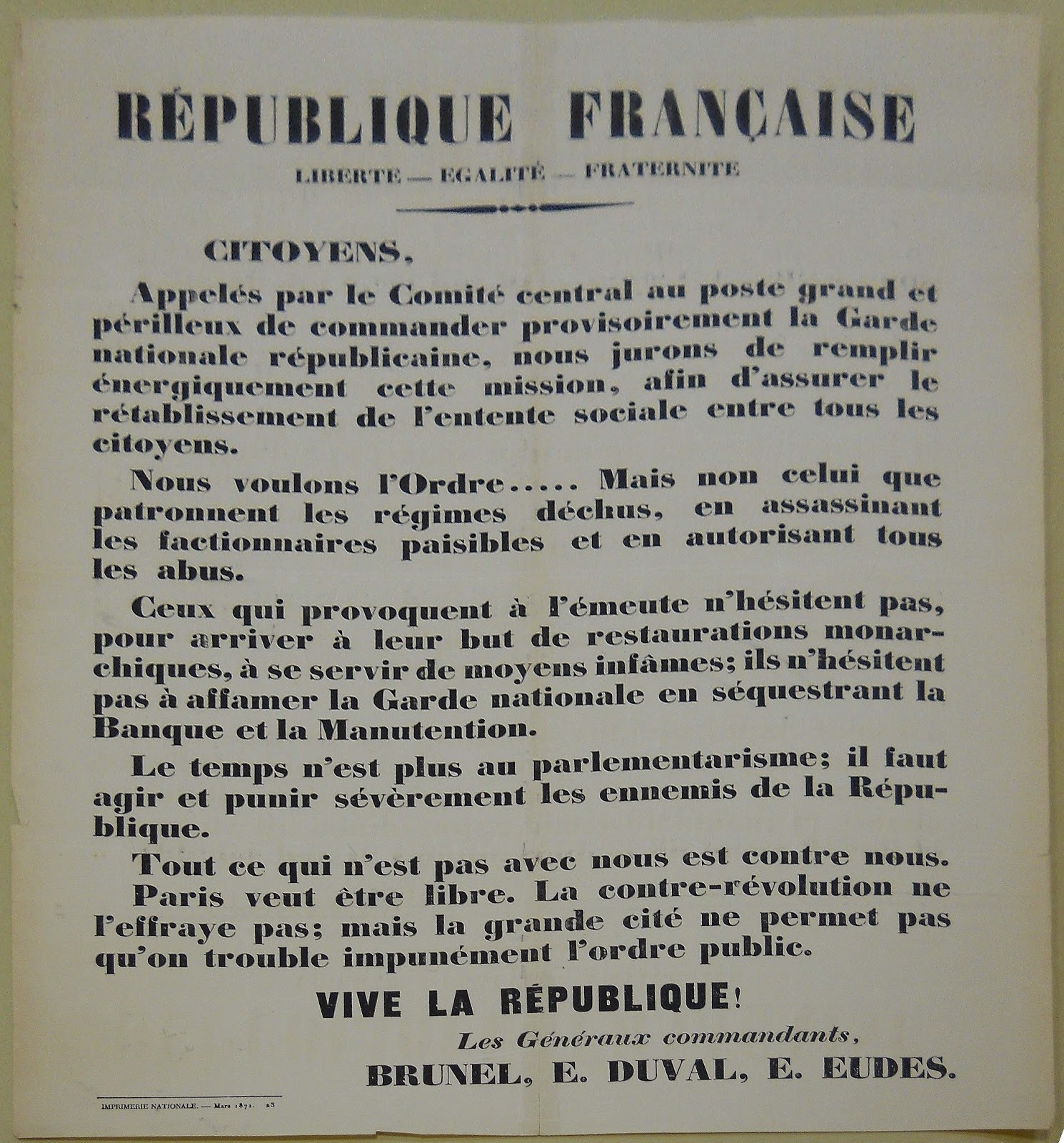

The commanders of the National Guard declare their intention to resist the forces of the counter-revolution: "It is no longer time for parliamentarism: we must act and severely punish the enemies of the Republic."

The commanders of the National Guard declare their intention to resist the forces of the counter-revolution: "It is no longer time for parliamentarism: we must act and severely punish the enemies of the Republic."

As rumors of the negotiations trickled into Paris, left-wing groups, including socialist followers of Louis-Auguste Blanqui and radical Republicans (or Jacobins), began to organize resistance to the planned armistice with the support of the citizen's militia of Paris, the National Guard. Their movements were also influenced by distrust of the Versailles government, which was dominated by monarchists and which was suspected of planning to restore the monarchy. In response to efforts by the Versailles government to disarm the National Guard and pacify Paris, a council calling itself the Central Committee of the National Guard prepared to defend the city. From early April to late May of 1871, the Communards battled troops loyal to the government at Versailles. The bloody repression of the insurrection by government troops and the execution of its leaders followed. The Commune has since occupied a place of special importance for political theorists of the left, perhaps most notably Karl Marx, who viewed it as the first historical example of rule by the working class.

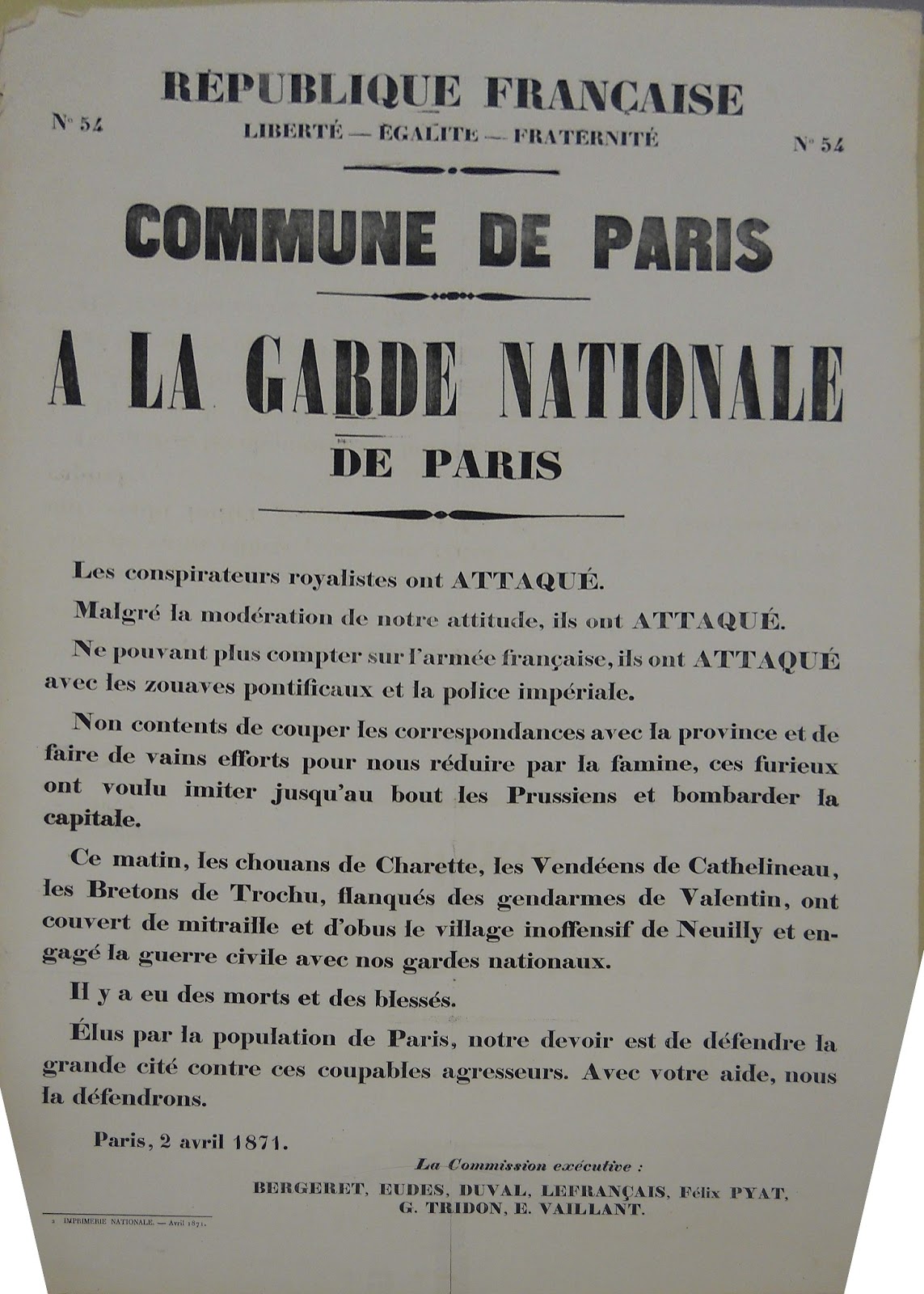

The collection at Brandeis consists of posters associated with notable events in the history of the Commune. One details the first outbreak of violence on April 2, 1871, framing it as an act of aggression by "royalist conspirators," who, "unable to count on the French army, have ATTACKED with Papal zouaves [soldiers] and Imperial police." The poster mentions unspecified casualties as a result of the attacks carried out by "these furious people," who, "not content to cut off communication with the province and to make vain efforts to reduce us through starvation […] wanted to imitate the Prussians to the end and bombard the capital." The message concludes by pledging that, "Elected by the population of Paris, our duty is to defend the great city (la grande cité) against the guilty aggressors. With your help, we will defend it."

The collection at Brandeis consists of posters associated with notable events in the history of the Commune. One details the first outbreak of violence on April 2, 1871, framing it as an act of aggression by "royalist conspirators," who, "unable to count on the French army, have ATTACKED with Papal zouaves [soldiers] and Imperial police." The poster mentions unspecified casualties as a result of the attacks carried out by "these furious people," who, "not content to cut off communication with the province and to make vain efforts to reduce us through starvation […] wanted to imitate the Prussians to the end and bombard the capital." The message concludes by pledging that, "Elected by the population of Paris, our duty is to defend the great city (la grande cité) against the guilty aggressors. With your help, we will defend it."

Another poster, from the last days of the uprising, details the plans of the Commune's leadership to confiscate the home and property of Adolphe Thiers, leader of the Versailles government. The order, carried out on May 13, was accompanied by another order to destroy a chapel that had been erected to commemorate the death of Louis XVI. [1] It identifies Thiers as "the bombardier," who, along with "the rural assembly, his accomplice," brought this treatment upon himself. In six articles, the declaration itemizes what is to be done with Thiers's property:

Article 1:

All of the linen originating from the Thiers house will be put at the disposal of the ambulances.Article 2:

The art objects and precious books will be sent to the national libraries and museums.Article 3:

The furniture will be sold at auction, after public exposition at the guardhouse.Article 4:

The profits from that sale will remain assigned only to pensions and indemnities that must be furnished to the widows and orphans of the victims of the infamous war that the ex-proprietor of the George residence has made upon us.Article 5:

The money that the demolition materials will bring in will go to the same destination.Article 6:

On the grounds of the residence, a public park will be established.

Both the Communards and the Versailles government made use of the official heading and motto of the French Republic, "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity." The Communard posters simply added specification as to which arm of the revolutionary leadership produced a given poster, and noted the date according to the French revolutionary calendar. This collection will be of interest to students of modern French politics and political culture, as well anyone who is interested in the history of the left-wing revolutionary tradition.