Public Sculpture at Brandeis

Numerous large sculptures enliven Brandeis’ physical campus, offering our community and visitors alike a fascinating tour of university history.

Below is a list of selected public sculptures and information about how each came to be part of the campus landscape. The student entries were written for an art history course taught by Professor Emerita of Fine Arts Nancy Scott in 2013.

Use the location links to create a walking tour, or just amble around the campus and enjoy discovering each artwork.

Location: Fellows Garden, on the hill outside the main entrance to Hassenfeld Conference Center

Whether it’s covered in white snow or bathed in glowing sunlight, the iconic statue of Justice Louis Brandeis atop the outcropping in Fellows Garden seems almost alive.

The nine-foot bronze figure, created in 1956 by noted sculptor Robert Berks to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Supreme Court justice’s birth, appears to capture the university’s namesake in mid-stride.

In fact, Berks’ wife, Dorothy, who was Brandeis’ personal assistant for 39 years, donned the justice’s personal robes against a beating wind on New York’s Staten Island Ferry to help the artist envision a sense of motion in his sculpture.

“He leans on his left leg, peacefully parrying the forces of opposition,” said Berks in a 1991 Boston Globe article about the sculpture. “Yet there is no aggression in his face or hands.”

The sculpture has given generations of students and countless campus visitors reason to pause by the outcropping and consider the outsized figure striding headlong into the wind, judicial robes sailing aloft behind him.

— Julian Cardillo ’14

Location: Chapels Field, in the woodsy area just northeast of Harlan Chapel

Maurice Beck Hexter was born in Cincinnati to German immigrants. He was a lifelong leader in social work and philanthropy, serving as director of the Federation of Jewish Charities and as a member of the United Jewish Campaign commission, which examined social conditions in Russia and Eastern Europe. Hexter played a key role in establishing the Heller School of Social Policy and Management at Brandeis and served on the university’s Board of Trustees. He received an honorary doctorate from Brandeis in 1961.

Relatively late in his life, Hexter took up sculpture as a pastime. He also created the distinctive black granite column outside Usdan Campus Center, titled Non-Objective.

— Zoe Messinger ’13

Location: Chapels Field, near Berlin Chapel and the Loop road

Rapaport’s bronze sculpture of the keening Job stands outside the Berlin Chapel in the architectural grouping of three structures honoring three Western religious faiths: Judaism, Catholicism and Protestantism. The chapels’ design was based on the master plan created by the Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, and they were built by the firm of Harrison Abramovitz in 1955.

The figure of Job embodies the weight of his suffering, turning his face toward the sky. In the multiple gathered folds of the cloak, and the clasped hands, Rapaport emphasizes Job’s chaotic disbelief in his abandonment. The sculpture is inscribed with a plaque from the Jewish Holocaust survivors in Boston to honor the memory of those who were sacrificed. The table below the sculpture is inscribed with a verse from Lamentations 3:48: “My eyes shed streams of water over the ruin of my poor people.”

— Nancy Scott, Professor of Fine Arts

From the Collection of the Rose Art Museum

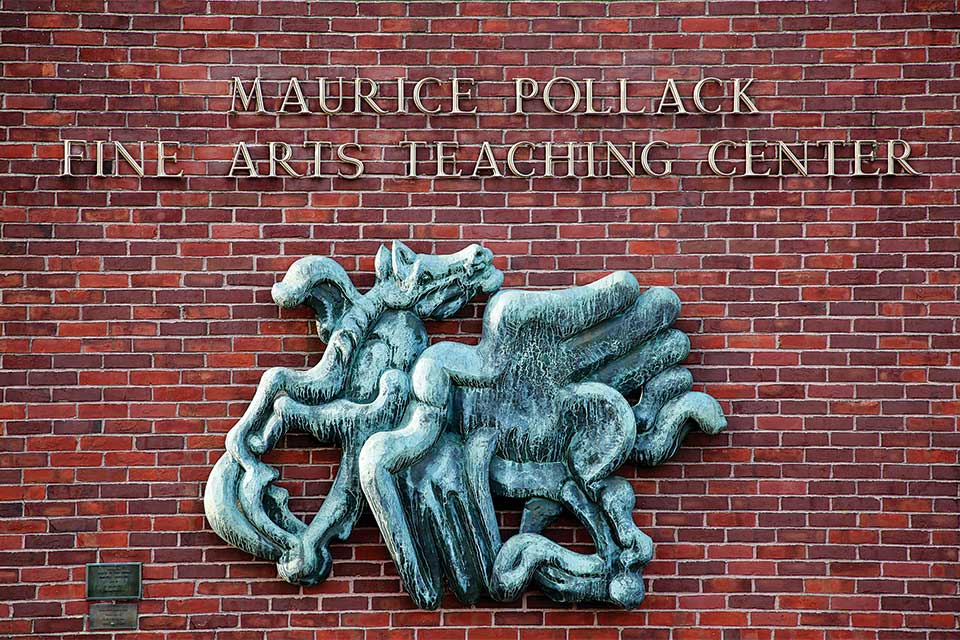

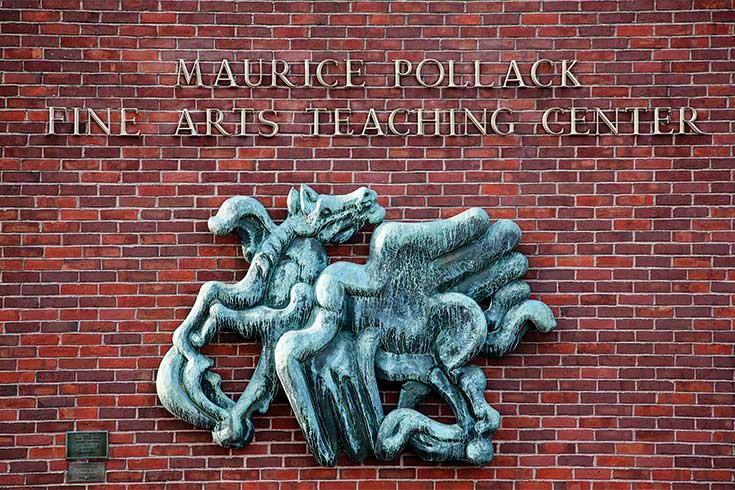

Location: On the exterior wall of the Pollack Fine Arts Teaching Center

Jacques Lipchitz was born in Lithuania and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and the Academie Julian in Paris. The original Birth of the Muses (Pegasus) was commissioned for Nelson Rockefeller’s guesthouse; subsequent casts can be found at MIT and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, as well as at Brandeis, where it was dedicated to honor Jack and Lillian Poses, founders of the Poses Institute, the precursor to the Rose Art Museum.

In the traditional telling of the Pegasus myth, the horse’s hoof strikes the Helicon spring and creates the Muses with each touch of the water. Lipchitz has the horse touch the top of Mount Olympus; the divine metamorphosis is about to occur, but the Muses await.

Lipchitz’s version of the story for the Rockefellers was meant to show the patrons’ deep support of the arts. Today, the bronze conveys the essence of artistic spark, to be displayed as Lipchitz intended, as an exterior relief.

— Sarah Hyman ’13

Gift of Leonard and Annike Farber

Location: President’s Garden outside the Irving Presidential Enclave

Chaim Gross began his art studies in Vienna at the Kunstgewerbeschule (“school of arts and crafts”) and continued in New York at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design and the Art Students League.

He worked primarily in the direct carving method, and thus initially created most of his sculptures in wood. He was also a professor of sculpture and printmaking at the New School for Social Research. By 1950, Gross worked mainly with bronze and in lithography. He was a member of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and founder and first president of the Sculptors Guild.

— Christina Kolokotroni ’13

Gift of Sandra and David Bakalar

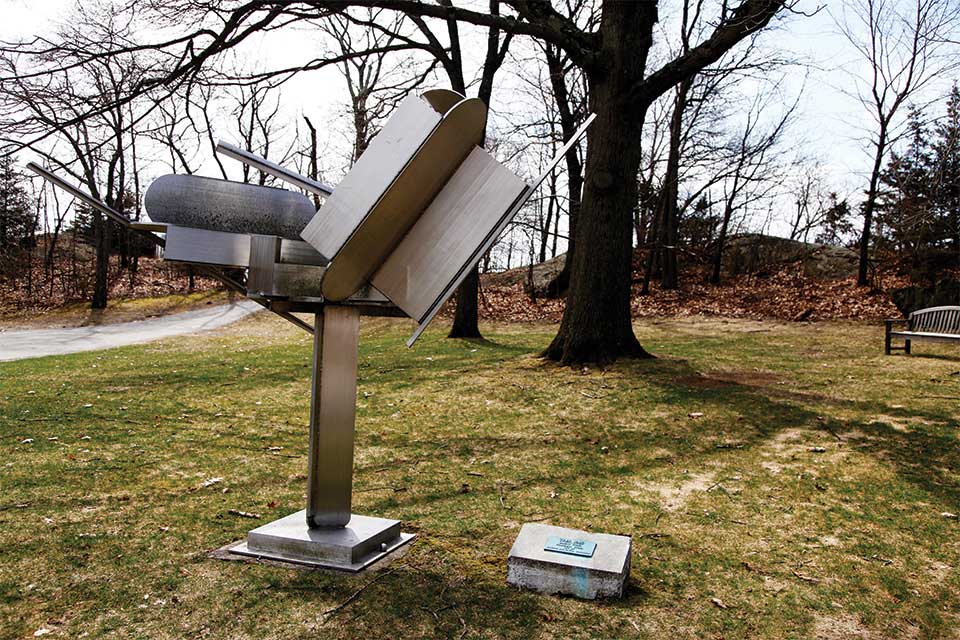

Location: Between the Pearlman Building and the Brown Social Science Center

Placed in a natural setting of trees and rocks, Tree both suggests and denies nature. In this work of innovative and technological modernism, sculptor Ernst Trova represents the trunk and branches of a tree through a stainless-steel rectangular post and angled forms extending outward to abstract geometric shapes.

— Lilli Gecker ’13

Location: In the grassy area between Loop Road and the Shapiro Science Center

Lila Katzen began her studies in New York at the Art Students League as a painter, and later graduated from Cooper Union. She turned to sculpture in the late 1960s, and by the mid-1970s began to make landscape-sited works in corrosion-resistant Corten steel. In the tradi- tion of David Smith and Richard Serra, Katzen rolled and curled heavy plates of metal, bending steel into shapes that resemble the lightness of paper ribbons.

Katzen produced a nine-inch wax model and then a 20-inch stainless-steel maquette for the Brandeis work. For its placement in front of the Rosenstiel Basic Medical Sciences Research Center, she designed curving Corten bases and created the landscaping around them. Later in 1983, Katzen’s recent work was featured in an exhibition at the Rose Art Museum.

The Wand of Inquiry, with a central flame-like element, resembles a coiling double helix. Its vertical balances the wide horizontal ribbon that unleashes an invisible force. The textured metal curves with the landscape and rises toward the sky.

— Nancy Scott, Professor of Fine Arts

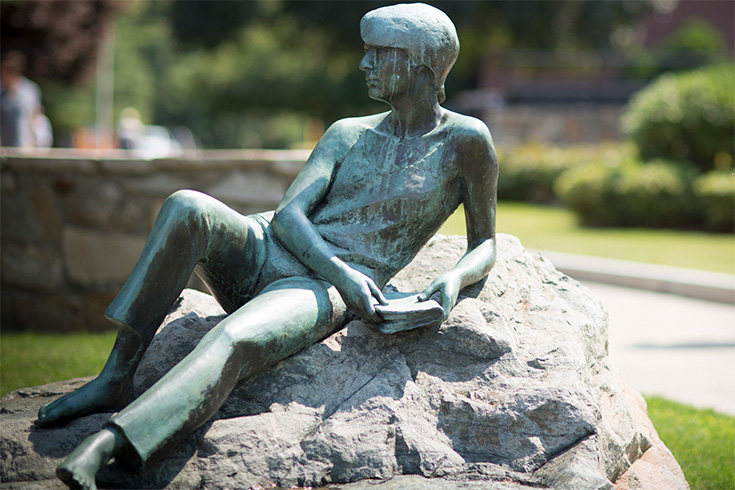

In the grassy area of the plaza in front of Goldfarb Library

Penelope Jencks taught at Brandeis in the 1980s as a Saltzman Visiting Artist, and sculpted “Student and Knowledge” at that time. She has created numerous works in terra cotta, bronze and stone. For this bronze figure, she pursued the casting of clay figures from life, and then fired the full-scale clay figure in a kiln, an innovative process she developed while at Brandeis.

Her sculpture is in private and public collections worldwide, but Jencks is perhaps best known for her monumental sculpture of Eleanor Roosevelt in New York City’s Riverside Park.

— Jackie Nullman ’13

On South Street, just outside the Epstein Building

Rita Blitt’s Inspiration is an abstract work created in painted steel. It was a gift to the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis, and marks the entrance to the center at the edge of the Brandeis campus. In 2005, Inspiration was a prizewinner in the acclaimed Florence Biennale.

Layered billowing shapes that contrast with the sculpture’s rigid steel evoke an abstraction of a woman, yet are also reminiscent of a bird in flight or hair blowing in the wind. Blitt is known for her monumental sculptures that convey swirling energy and movement, as if time has stood still. Her style speaks to all cultures and people, as she touches on the universal themes of humanity, movement and beauty.

— Anna Khazan ’13

Inside the Mandel Center for the Humanities

Martin Dermady’s architectural design for the Mandel Center for the Humanities synthesizes form, structure and function, reflecting the complexity of humanities study. The light installation Campus Constellation, also designed by Dermady, provides a visual focal point for the center’s three-story atrium.

A computer algorithm sets the installation’s constantly changing color and pattern. While each lighting element has autonomy, together they work as a unit, just as the humanities disciplines function at Brandeis. Despite its scale, the space feels intimate. Tall windows and a wood-paneled seating area allow for reading or contemplation of the “constellation,” which is visible at night from various outdoor sites on campus, leading the eye to the Mandel Center.

— Rebecca D. Pollack ’13

Commissioned from the artist by the Rose Art Museum, 2012–2013

Immediately in front of the Rose Art Museum

Light of Reason, a site-specific sculpture installation designed for the Rose Art Museum, is the last completed work by the Boston- born artist Chris Burden (1946–2015).

Burden salvaged the 24 cast-iron lampposts from a 1920s civic project in Los Angeles and restored them at his Topanga Canyon, California, studio. Modern LED lights create a swath of light that enlivens the broad concrete plaza (also Burden’s design) and welcomes the nocturnal walker.

The work was inaugurated in September 2014 with a dedication by Fred Lawrence, Brandeis’ eighth president; music by the Lydian String Quartet; and a silent protest, led by about 50 students demon- strating against the university’s response to sexual violence.

There are important precursors to Light of Reason. Though Burden is known for performance art in the 1970s that often placed his own body at risk, he later turned to projects such as 14 Double Magnolia Lamps (2006) and the popular Urban Light (2008) for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, in which 202 street lamps form a dense cluster of differing styles and heights.

For the Brandeis project, Burden created a design that suited the pastoral suburban campus and evoked the university’s founding principles. From the Brandeis seal, he extrapolated the formal element of threes: three flames of light above Boston’s original three hills, and three Hebrew letters that spell the word emet (truth). For the artwork’s title, Burden turned to the words of Justice Louis Brandeis: “If we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold.”

Burden described the design as reaching out to “point people to the museum.” The three concrete slabs that support the lamps serve as a peaceful spot “to sit, read a book, chat with a friend, or eat a sandwich,” he wrote.

The museum’s then director, Chris Bedford, regarded the work as “a new beginning” for the Rose. In a recent conversation, Bedford called it "a democratic outdoor space...never meant to be scripted,” open to the campus community and beyond. Bedford has noted that Burden’s early performance work “threw into high relief the most pressing political questions of the day,” and though his late work is far different, the artist’s interest in creating “social space” never changed.

Every fall, a new undergraduate class gathers at the lights for a welcome ritual. The sculpture serves as a concert and dance stage in the annual Festival of the Arts and as a year-round site for selfies. And the Light of Reason will shine on the museum’s 60th anniversary in 2020, continuing to draw students and visitors to the Rose.

— Nancy Scott, Professor of Fine Arts

On the Loop Road, opposite the Shapiro Admissions Center

Harold Grinspoon, a longtime friend of the university, began his art career in 2013 at age 84. Since then, he has completed more than 100 sculptures, many installed in public spaces across Massachusetts and nationally. Twister, on loan to Brandeis, is inspired by a tornado that churned through Grinspoon’s home town of Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

— Ingrid Schorr, Director, Brandeis Arts Engagement