The Islamic Republic of Iran’s Chastity and Hijab Law and the Weaponization of Women’s Economic Vulnerabilities

Iranian women in Tehran without headscarves in September 12, 2023. (Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via AP)

Middle East Brief No. 162 | December 2024

On December 14, 2024, in an unprecedented move, the Supreme National Security Council, a twelve-member body tasked with ensuring Iran’s foreign and domestic security, intervened to halt the controversial “Chastity and Hijab” bill from becoming law. The 74-article legislation, which had been in the works since May 2023, proposed substantial economic penalties on individuals and businesses violating Iran’s mandatory dress code for women. In essence, the bill targets the economic welfare of households across all social classes, using financial pressure to ensure compliance with the Islamic Republic’s hijab policy of over four decades.

The hijab bill, as it is frequently called, has been widely criticized inside and outside Iran, including by President Masoud Pezeshkian, who was elected in July 2024 partly on a platform of social and personal freedoms. Pezeshkian openly criticized hardliners supporting the measure, asserting that his administration cannot implement such a controversial and unfair law. He further warned that enforcing it would spark widespread public discontent, as many Iranians would refuse to comply with such stringent regulations. [1] Nonetheless, Parliament Speaker Mohammad-Bagher Ghalibaf had confidently promised that the bill would be enacted by December 13, 2024, vowing to end months of uncertainty and increased public dissatisfaction. However, the bill now languishes in legal limbo following this unprecedented intervention. Adding to the turmoil, Iranian law provides no clear guidance on how long an approved measure can remain suspended, fueling speculation over whether this proposed hijab law—potentially the most comprehensive since the 1979 revolution—will ever be enacted.

The introduction of the “Chastity and Hijab” bill and its uncertain fate is a perfect opportunity to ask: Why are Iranian hardliners pushing for even stricter hijab laws as a reaction to the momentous events of Fall 2022 known as the Women, Life, Freedom movement? Why is the government considering steep economic penalties as punishment despite widespread calls from within to end compulsory hijab? Finally, how does the emphasis on financial penalties signal a broader shift in the state’s approach to social control, particularly over women’s bodies?

This Brief argues that the proposed new hijab law reflects the recognition that women’s economic advancements have enhanced their social presence and empowered them to challenge the state’s desired social order and values—yet, despite these gains, women remain particularly vulnerable to economic hardship, exacerbated by the impact of U.S. economic sanctions. The bill exploits these vulnerabilities, leveraging the risk of poverty and unemployment to reinforce the regime’s social order. By linking citizens’ economic and social rights to adherence to prescribed norms, the bill transforms the decision to wear the hijab from a personal choice into an economic necessity. Altogether, the Brief aims to demonstrate that although economic penalties have been part of hijab enforcement since the 1990s, the newly proposed law would escalate both the severity and the scope of these financial measures, marking a shift in the state’s enforcement strategy for the compulsory hijab. This change underscores the evolution of women’s socioeconomic progress vis-à-vis their political freedoms under the Islamic Republic, highlighting how economic factors can act both as tools of repression against women in Iran and as catalysts for Iranian women’s rights movements.

The Evolving Politics of Hijab in Iran

The hijab, which refers to Islamic modest dress for women, including covering hair as well as loose-fitting clothing that covers the body, has played a complex and multifaceted role in Iran’s political and social landscape, extending far beyond that of a symbol of piety and modesty. Before the 1979 Iranian revolution, the hijab was politicized as a symbol of resistance against the Pahlavi regime, [2] and against Western imperialism in urban settings. [3] After the revolution, compulsory hijab became a central element of the Islamic Republic’s social order, [4] embodying the state’s commitment to Islamic principles and distinguishing it from the prior regime and from Western societies. Though there was initially pushback against it, most notably during the women’s demonstrations of March 1979, by July 1980 the Revolutionary Council had mandated it for all government employees, barring women without proper Islamic covering from entry into government offices.

Since then, the hijab has symbolized ideological identity and allegiance to the Islamic Republic, serving to rally supporters and strengthen its base. In an April 3, 2024 address, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei highlighted the hijab’s centrality, calling it both a religious and legal duty and accusing foreign adversaries of orchestrating opposition to revive pre-revolutionary social norms. [5] His remarks echo hardline arguments that relaxing hijab enforcement erodes the Islamic Republic's support base, blurs the distinction between it and secular regimes, and undermines its stability. [6] By framing the hijab as a security necessity, Khamenei underscored its role as both symbol of the regime’s authority and a foundation of its adherence to Islamic values and its supporters’ loyalty.

But since the Women, Life, Freedom movement of 2022, a growing number of women have chosen to forgo wearing the hijab in public, reflecting a significant shift in societal attitudes. In response, the government has attempted to enforce hijab compliance through measures such as reinstating the morality police and implementing new surveillance measures. These efforts have largely failed, forcing authorities to rethink their approach. One reason for the failure of these efforts and others over the past decades is the gradual decline in support for compulsory hijab within Iranian society as indicated by several official surveys. [7] Before 2000, at least 50 percent of respondents supported the compulsory hijab; this support decreased to 23 percent by 2016 and to 16 percent by 2024. And a recent unpublished survey conducted by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance reveals that 84 percent of respondents disagree, to some extent, with imposing the compulsory hijab policy.

Recent surveys also consistently show an increase in support for voluntary hijab increasing from 38 percent in 2003 to 78 percent in 2015. [8] And a government estimation in 2017 suggested that over 70 percent of Iranian women do not comply with the official hijab definition. [9] This shift in public opinion—from declining support for the compulsory hijab to rising support for voluntary practices—continues to pose a substantial challenge to the post-revolutionary social order.

Economic Implications of the Post-revolutionary Social Order

Although the post-revolutionary Islamic state curtailed Iranian women’s social and economic rights in many areas, the new Islamic state-enforced social order also facilitated new opportunities for large segments of Iranian society. [10] The post-revolution gender segregation policy in the educational system encouraged many religious families to send their daughters to high school and university. It also expanded female employment opportunities in sectors like education, health care, retail, and other services catering specifically to women. In some cases, this segregation provided women with privileged access to job opportunities and positions in higher education, allowing them to enter these spaces without direct competition from male counterparts. [11]

Overall, during the 1990s and 2000s, sustained economic growth contributed to a significant increase in female employment and an improvement in women’s socioeconomic status. Although the female economic participation rate in Iran remains one of the lowest in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)—hovering between 15 and 18 percent—there have been notable structural transformations within the female labor market since at least 2010. A combination of higher educational attainment and efforts against wage discrimination has driven more women to seek higher-skilled occupations. This progress has amplified women’s aspirations for a more prominent and equal role in society.

The shift in gender dynamics is especially evident in the realm of education. Since the revolution, the female literacy rate increased almost 3.5 times, rising from 25 percent in 1976 to 85 percent in 2022. [12] According to Iran’s Statistical Center, the proportion of female students in the country's universities has doubled, from 25 percent in 1970 to 50 percent in 2020. The most notable gains have been in traditionally male-dominated fields such as engineering and agriculture, where female participation rose from just 4 percent and 2 percent, respectively, in 1980 to 25 and 55 percent in 2020. By 2023, 50 percent of women aged 20 to 24 held a higher education degree, compared with 41 percent of men in the same age range. [13] In highly competitive medical and science degree programs this disparity is even more striking, with women now making up 70 percent of students. [14] By 2023, all women aged 15 to 55 outpaced their male counterparts in educational attainment.

In addition to increased access to higher education and improved health care for women, several other factors—such as delayed marriages and childbirth, lower fertility rates, and a rising divorce rate—have shaped the scope and nature of women’s social presence and participation in the labor force. For example, in 1979, the average Iranian woman had a life expectancy of 57 years and raised 6.5 children. By 2020, the female life expectancy had increased to 78 years, while the fertility rate had dropped to 1.75. [15] That is, since the 1979 revolution, women have had an average of nearly five fewer children while living 21 years longer.

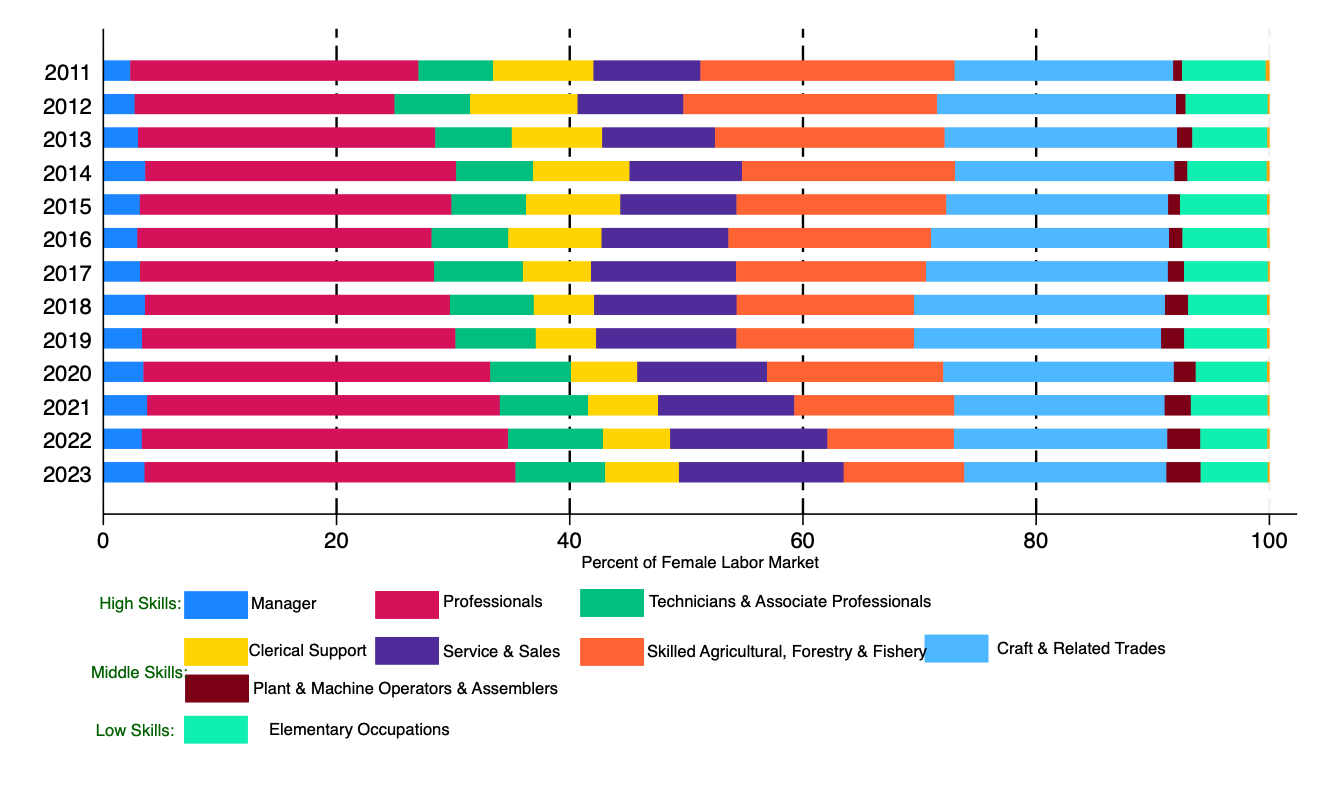

Figure 1. Iran’s Female Labor Market: Major Occupation Groups from 2011 to 2023

Source: Author’s analysis based on Iran’s Labor Force Survey, administered by the Iran Statistical Center, 2010 to 2023.

Over the last decade, Iran’s female labor market has undergone a significant structural transformation, with a higher percentage of women working in higher-paying jobs or choosing to leave lower-paying ones. A detailed review of the country’s Labor Force Survey (LFS) from 2011 to 2023 indicates the proportion of women in low- and middle-skilled jobs decreased by 10 percent, while the share in high-skilled occupations rose from 33 to 43 percent (see Figure 1). [16]

One factor contributing to the decline in women in middle-skilled positions is their reduced presence of women in Iran’s agricultural sector, where female employment dropped from 22 percent to 11 percent. The growth in high-skilled positions includes managers, professionals, and technicians and associate professionals—mainly in the public sector, but also in newly created private-sector jobs in education and health care, among other fields. These specialized and managerial jobs are more resilient in the face of economic shocks such as economic sanctions and pandemics, owing to their stability and higher salaries as well as to Iran’s generous welfare system. [17]

Moreover, there has been a significant decline in women’s interest in low-paid or unpaid positions, reflecting a growing demand for fair compensation. Despite economic pressures, about 20 to 30 percent of employed women, particularly those aged 25 to 40, have left the labor market owing to insufficient wages or perceptions of wage discrimination, primarily in middle-skilled occupations in the private sector. Using another occupation classification, while 25 percent of employed females were classified as contributing family workers in 2011 (essentially unpaid self-employment in the private sector), that share dropped to 12 percent in 2023.

Yet, despite positive trends in women’s employment, macroeconomic conditions have played a critical role in shaping the female labor force in Iran. Between 2015 and 2018, when certain U.S. economic sanctions were briefly lifted under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), women filled nearly 41 percent of newly created jobs, and female economic participation rose from 12 percent to 18 percent. Specifically, out of 3 million newly created jobs during this period, women secured 1.2 million positions, while men obtained 1.8 million.

This progress was reversed, however, after the U.S. reimposed sanctions in 2018, and the effect was magnified by the economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic. By 2020, the female labor participation rate had dropped back down to 13 percent, and the female labor market had contracted by 19 percent. Between 2018 and 2020, Iran’s labor market lost 826,000 jobs overall: Women lost approximately 800,000 jobs—primarily in middle-skilled positions within industry, services, and agriculture—while men lost 21,000. These data highlight the vulnerability of women’s economic advancements to macroeconomic shocks, and the way that these shocks have disproportionally affected female employment opportunities. In 2022 and 2023, following a new wave of economic growth indicating post-pandemic recovery and resilience to sanctions, Iran’s economy created one million new jobs. Although women did not regain their pre-sanctions share, they secured 400,000 of these new positions, accounting for 40 percent of the total.

Women’s higher education and improved economic status have expanded their social presence, shifted gender power dynamics, and fueled demands for greater gender equity and freedom in Iran. But fluctuations in women’s labor force participation—marked by significant gains during periods of economic growth and steep declines during economic contraction—reveal the precariousness of their economic progress, and the tenuousness of their employment gains.

A Feminist Uprising against Compulsory Hijab

In September 2022, the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman, while in police custody for allegedly not wearing her hijab appropriately ignited a public outcry and widespread protests against the Islamic Republic under the banner of the Women, Life, Freedom movement. [18] Hailed by some as the first feminist uprising in the Middle East, [19] the protest was unprecedented in its focus on women’s rights and for the prominent role of young women. For many women, it was a transformative experience of crossing enforced boundaries and rethinking their place in society. [20] What began as grievances about the hijab expanded into broader demands for political and social changes that challenged the very foundations of the Islamic Republic.

The initial response to the protests was swift and severe. In the first three months of the protests, over 480 protesters lost their lives, with hundreds injured and blinded and more than 18,000 individuals arrested in 160 cities and at 143 universities across the country. [21] According to a recently published report by the President’s Special Committee, 34,000 court cases were filed during the unrest, though 22,000 of these cases were closed after the Supreme Leader’s amnesty in February 2023, and only 292 individuals were sentenced to prison. [22]

The authorities also launched a massive surveillance campaign targeting women in public spaces to enforce the compulsory hijab. Hundreds of thousands of vehicles carrying passengers deemed inappropriately dressed were confiscated, and numerous cafes, bookstores, and women’s hair salons in major cities temporarily closed. While the exact figures for confiscated vehicles and closed businesses are unclear, interviews conducted by the author suggest that nearly every cafe in large cities, such as Mashhad and Isfahan, has been shuttered at least once since 2023. Between March and April 2023, close to one million messages were sent to vehicle owners warning that a passenger was wearing an inappropriate hijab. [23] A vehicle that receives three such warnings is confiscated for up to two weeks and the owner incurs hefty fines, suggesting that about two percent of all Iranian vehicles received at least one such notice in March 2023 alone.

Though the scope and scale of the protests largely subsided after several months, the new repression measures and surveillance campaign have failed to return the hijab mandate to its pre-protest status. Many women are now choosing not to wear the hijab on large city streets, marking a visible change in social norms surrounding the hijab in Iran.

The Transformation of Hijab Enforcement in Iran

In May 2023, nearly nine months after the start of the Women, Life, Freedom protests, Iran’s judiciary drafted an initial nine-article proposal known as the hijab bill and submitted it to then president Ebrahim Raisi’s office. The Raisi administration expanded the draft by adding six more articles and forwarded it to Parliament on June 1. The Parliamentary Judicial Commission significantly revised the bill, increasing it from 15 to 74 articles. Notably, only one woman was involved in the initial drafting, despite the bill’s profound implications for women's rights. By the end of July 2023, the Commission sent the final draft to the Guardian Council, the body responsible for vetting all parliamentary legislation. In September 2024, the Guardian Council approved the bill and returned it to Parliament for further legal procedures. Ironically, the final approval coincided with the second anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death and the beginning of the Women, Life, Freedom movement. The law, officially titled the “Law to Protect the Family by Promoting the Culture of Chastity and Hijab,” was thus enacted on a date that underscored the very issues it controversially addressed.

As the last major legislative act mandating compulsory hijab since the 1979 revolution, the proposed new law marks a significant shift from physical punishments to substantial economic penalties. The first legal enforcement of compulsory hijab for all women—including non-Muslims, foreigners, and tourists—was established in Iran’s Islamic Penal Code in April 1983. According to Article 102, Section 1 of the Penal Code, women appearing in public without a hijab could face ta’zir (discretionary punishment), potentially resulting in up to 74 lashes. The hijab law was most recently updated in 1996 under Article 638 of the Islamic Penal Code, stipulating that women deemed to have inappropriate hijab could face imprisonment ranging from ten days to two months or fines between 50,000 and 500,000 Iranian rials ($7 to $70 at the time).

Unlike past enforcement measures that relied on physical policing, the proposed law would introduce comprehensive and explicit guidelines detailed in 74 different articles, targeting both men and women. The most notable change is the sharp increase in fines for violations that increase with each subsequent infraction (see Figure 2). Although economic penalties have been a part of hijab enforcement policy since the 1990s, the bill represents a transformation in their application, with increased fines and broader implications for non-compliance. The bill also represents a sweeping expansion of the state’s efforts to enforce dress and behavior regulations far beyond any previous measures (see Figure 3). For example, the bill imposes penalties on artists, celebrities, freelancers, and private companies for violating dress codes in public or posting inappropriate images on social media. Articles 2 through 34 assign specific responsibilities to nearly all government bodies to promote the “Islamic hijab” in society. Notably, for the first time, the bill allows foreign immigrants and legal refugees to participate in its enforcement, including monitoring, reporting violations, and advocating for hijab.

Figure 2. List of Fines by Degree of Offense in the Islamic Penal Code

|

Fines according to Article 19 of the Islamic Penal Code applied since July 2023 |

||

|

Degree of offense |

Million Iranian rials |

U.S. dollars ($1 = 600,000 rials) |

|

1st |

9,200 |

$15,300 |

|

2nd |

5,000 to 9,200 |

$8,300 to $15,300 |

|

3rd |

3,300 to 5,000 |

$5,500 to $8,300 |

|

4th |

1,650 to 3,300 |

$2,700 to $5,500 |

|

5th |

800 to 1,650 |

$1,300 to $2,700 |

|

6th |

200 to 800 |

$330 to $1,300 |

|

7th |

100 to 200 |

$160 to $330 |

|

8th |

100 |

$160 |

Source: Estimated by author based on Islamic Penal Code applied since July 2023

Note: According to Article 28 of the Islamic Penal Code, the minister of justice shall adjust all monetary fines according to the inflation rate announced by the Central Bank every three years.

Figure 3. Individual Penalties for Violations of Hijab

|

Violation Type |

1st Violation |

2nd Violation |

3rd Violation |

4th Violation |

5th Violation |

|

Nudity (Female/Male) |

$5,500 to $8,300 or up to 10 years in prison |

$15,300 or above, 25 years in prison |

|||

|

No head covering (Female) |

Warning with $80 fine suspension for 3 years |

$80 + $160 |

$330 to $1,300 |

$1,300 to $2,700 |

up to $15,300 |

|

Inappropriate dress (Female/Male) |

Warning with $80 fine suspension for 3 years |

$80 + $160 |

$330 to $1,300 |

$1,300 to $2,700 |

up to $15,300 |

|

No head covering and inappropriate dress |

Warning with $80 + $80 fine suspension for 3 years |

$80 + $160 $80 + $160 |

up to $2,600 |

up to $5,400 |

$15,300 |

|

If in a public setting (religious places, government buildings, and public gatherings above 100 people) |

up to $15,300 |

||||

|

If public sector employee |

In addition to the fine, 6-month suspension from working for each violation, and no job promotion |

||||

|

If celebrity or public figure |

· Up to $15,300 fine + 1 to 5% of total registered assets · Up to six months of disqualification from professional and social influence activities · Travel ban for up to two years · Prohibited from public activities on social media for up to two years · Stripped of tax exemptions for two years |

||||

|

If NGO board member |

Must be removed from their position within one month—otherwise, the organization’s license will be revoked |

||||

|

If unable to pay fine |

· Provision of passport services, issuance of country exit permits, motor vehicle registration, license plate, and driver’s license will be suspended · Bank account will be frozen, except for 10% of the fine amount |

||||

|

If a foreigner (non-Iranian) |

Passport will be confiscated |

||||

While the proposed law’s stated objective is to disband the morality police, it reflects the government’s acknowledgment of the failure of traditional enforcement methods like physical punishment and street-level policing. With an increasing number of Iranian women defying the hijab mandate, the bill offers a more expansive control mechanism. Despite a surge in security spending following the reimposition of U.S. sanctions in 2018—including a 14-fold increase in the budget for police suppression equipment between 2019 and 2021 [24]—the government has shifted toward economic penalties. This shift is less about economic penalties being less controversial or drawing less international criticism and more about their perceived deterrent effect in the context of Iran’s worsening economic hardships. The bill operates on the assumption that citizens’ economic vulnerabilities will compel compliance with state-prescribed social values, which are fundamental to the regime’s raison d'être.

Weaponization of Economic Vulnerabilities

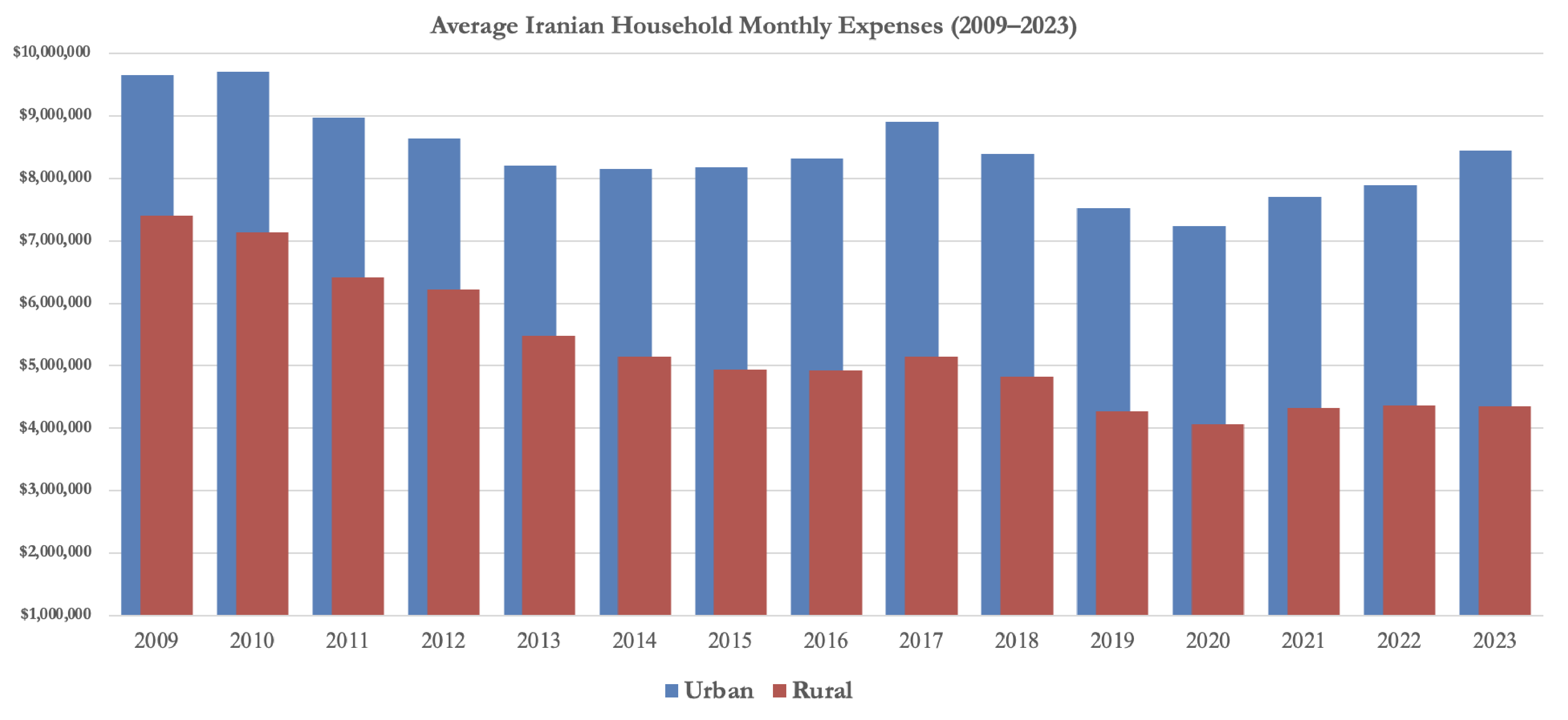

Iran’s economic hardship over the last decade, owing to economic sanctions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and mismanagement, has deepened the country’s poverty crisis. High inflation has eroded the purchasing power of Iranian households. Between 2010 and 2020, average household spending contracted by 25 percent in urban areas and 43 percent in rural areas (see Figure 4). Although household spending increased by 16 percent in urban areas and 7 percent in rural areas during 2022 and 2023—indicating post-pandemic recovery and some resilience in the face of sanctions—overall household welfare levels have not yet returned to their pre–U.S. sanctions levels of 2011, particularly for rural residents.

Figure 4. Average Real Household Monthly Spending in Urban and Rural Areas of Iran (2009–2023)

Source: Author’s analysis based on the Household Expenditures and Income Survey administered by the Iran Statistical Center, 2009 to 2023.

Note: Expenses have been deflated and adjusted based on the 2021 Consumer Price Index (CPI) for both urban and rural areas.

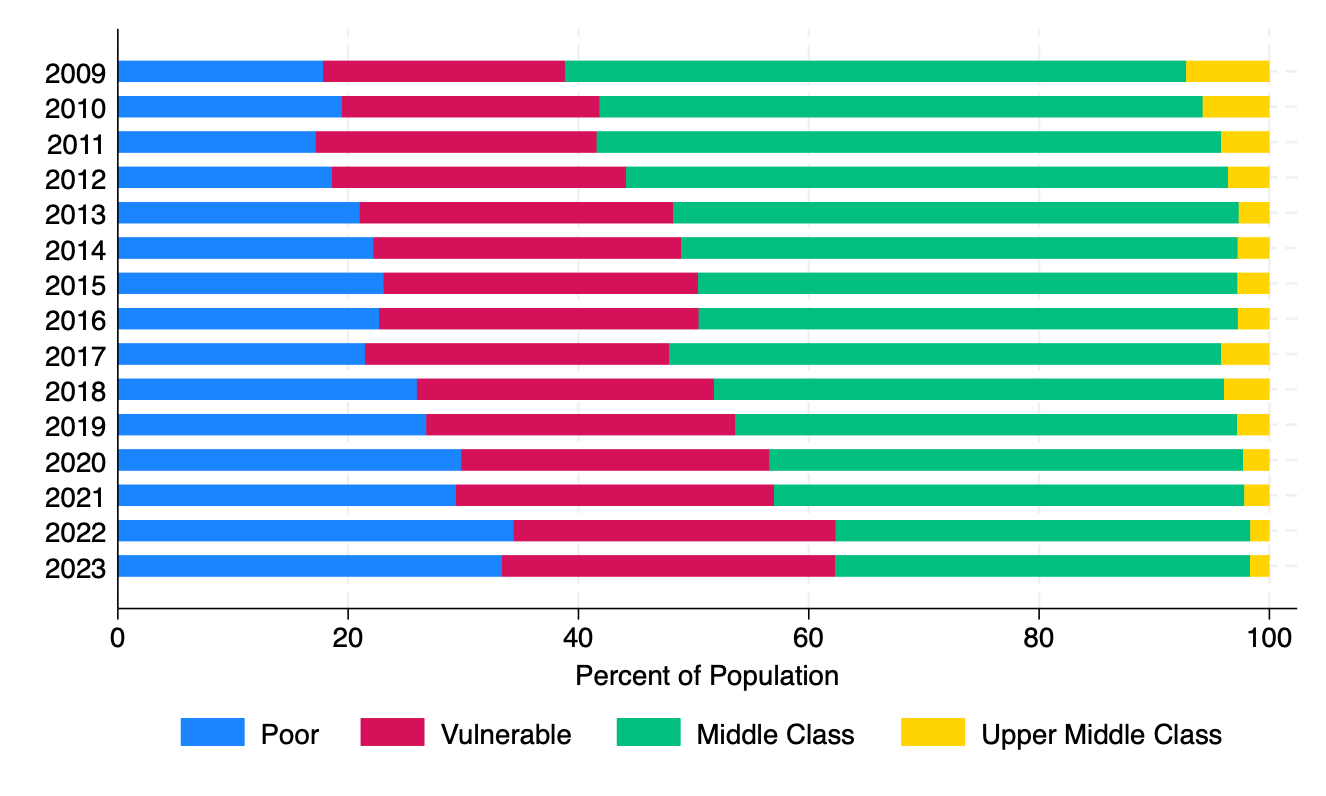

A detailed analysis of Iran’s Household Expenditures and Income Survey (HEIS) reveals that the poverty rate nearly doubled over the past decade, rising from 17 percent in 2011 to 34 percent in 2023 [25] (see Figure 5). Including vulnerable populations—those who are not currently poor but are at risk of falling into poverty—this figure climbs to nearly 62 percent of Iran’s population, or approximately 53.5 million people. These figures represent households whose annual incomes in 2023 were below $3,400 in urban areas and $2,600 in rural areas.

Figure 5. Iranian Economic Class Structure (2009–2023)

Source: Author’s analysis based on Iran’s Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES), 2009 to 2023.

The proposed hijab law could impose catastrophic financial burdens on individuals and households that violate its provisions—costs that are unaffordable for 62 percent of Iranian families. For example, if any household member is caught breaking the law for a second time—say, by wearing inappropriate clothing without a head covering—the resulting fine could be as high as $480. This fine would represent a significant portion of annual income: 30 to 50 percent for poor families, 15 to 30 percent for vulnerable families, and 7 to 15 percent for middle-class families. Such penalties could place considerable strain on these households, diverting funds from essential expenses like food, housing, and health care. Additionally, individuals who refuse to pay or cannot afford the fines would face further penalties, including the suspension of passport services, vehicle registration, license plates, and driver’s licenses. They would also not be allowed to leave the country, and their bank account could be frozen—except for a limited amount equivalent to 10 percent of the fine.

Beyond the financial strain of the fines, the proposed hijab law could have severe consequences for women’s economic status: Violations could result in job termination or suspension. For example, public sector employees who violate the hijab law—even outside their workplace—could face suspension for up to six months with no subsequent job promotion. These jobs are often in high-skilled sectors that have proven more resilient to macroeconomic shocks than middle- or lower-wage positions. Thus, even upper-middle-class women in high-skilled public sector jobs, who might be able to afford the fines, risk losing their positions if they violate the law. The combined threats of job loss and financial penalties would ensure that women across all economic classes are adversely impacted by this legislation—if enacted.

Additionally, the severe economic penalties proposed under the law are likely to affect business owners, especially those in the service sector. Under Article 41, business owners who promote nudity, indecency, or improper clothing could face fines of up to $8,300 or two months of profits, whichever is higher, and a travel ban of up to two years. For repeat offenses, these penalties increase to fines of up to $15,300 or four months of profits, with the travel ban remaining in place. Article 42 further penalizes business owners if anyone violates the law on their premises, with fines up to $2,700 or four months of profits, and a travel ban of up to two years. These severe financial penalties may discourage many business owners, especially those in the service sector, from hiring women, potentially stalling the advancement of women in the workforce.

The hijab bill also targets civil society activities and board members of NGOs. If a board member of an NGO violates the law, they must be removed from their position within one month; failure to do so could result in the revocation of the NGO’s license. Taxi and ride-hailing drivers also face fines of up to $80 if their passengers violate the law, unless they report the violation. Iran’s ride-hailing services include more than 3.5 million active drivers, accounting for approximately 15 percent of the country’s labor market. If a passenger commits an offense, the vehicle or motorcycle will be immediately impounded for one week, in addition to the fines.

The focus on economic penalties in the proposed law reveals the limitations of physical coercion. At a time when the use of force could further exacerbate public dissent, the weaponization of economic vulnerabilities—especially amid growing economic hardship—is seen as a more effective tool than other punitive measures. But many Iranians remain skeptical that the new law will succeed in reversing social attitudes and restoring the status quo. President Pezeshkian has criticized hardliners supporting the law, expressing concerns about its enforceability and potential to undermine national unity. [26] Although the president lacks the authority to veto legislation passed by Parliament, the Supreme National Security Council’s decision to suspend the law’s enactment underscores deep apprehensions within the government. This unprecedented move marks uncharted legal territory for the Islamic Republic, exposing growing fractures within its ruling establishment over ideological priorities.

Conclusion

Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic, compulsory hijab has been a cornerstone of an enforced social order, embodying the regime’s adherence to Islamic values and principles and thereby strengthening ties with its base. More importantly, it serves as a tool for political consolidation, rallying supporters and ensuring their ideological alignment. This social order has been increasingly challenged, however, by growing resistance among Iranians, particularly after the Women, Life, Freedom protests. The Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Khamenei perceives these challenges as signs of de-revolutionization and Westernization. In his April address, Ayatollah Khamenei sought to articulate the dual imperatives of condemning external aggression and reinforcing internal compliance with Islamic norms. By linking the enforcement of hijab to a broader narrative of resistance against perceived Westernization and counter-revolutionary forces, Iran’s Supreme Leader aims to fortify his base by demonstrating the regime’s commitment to Islamic principles.

This Brief has argued that through the proposed hijab law, the Islamic Republic seeks to leverage economic instruments to restore its enforced social order, rather than relying primarily on physical coercion. But the rise in women’s economic status has expanded their social presence and empowered them to challenge this order— and increased access to higher education and high-skilled jobs has opened new opportunities for Iranian women to voice their demands. Yet, despite these advancements, Iranian women remain highly vulnerable to economic hardship, especially under the pressure of U.S. sanctions. This economic vulnerability enables the government to use financial penalties as a means of controlling the social presence and visibility of women. If enacted, the hijab law could have significant implications for Iranian women, potentially reversing their economic and social advancements in recent years.

Iranian women have demonstrated a remarkable ability to navigate and resist the regime’s repressive cultural policies, often finding creative ways to circumvent imposed restrictions. Despite the hardline faction’s hopes that the proposed law will serve as an effective deterrent, its impact and enforceability remain uncertain.

Hadi Kahalzadeh is a junior research fellow at the Crown Center.

For more Crown Center publications on topics covered in this Middle East Brief, see “The Evolution of Iran's Police Forces and Social Control in the Islamic Republic,” “Iran’s Overeducation Crisis: Causes and Ramifications,” and “Shut Out of Good Jobs: Contemporary Obstacles to Women’s Employment in MENA.”

Endnotes

[1] Maryam Sinaiee, “Pezeshkian Says New Hijab Law Cannot Be Enforced,” Iran International, December 3, 2024.

[2] Parvin Paidar, Women and the Political Process in Twentieth-Century Iran [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Middle East Studies), 1997].

[3] Nazanin Shahrokni, “Bodies in Revolt: Challenging the State in Iran,” Current History 122, Issue 848 (December 2023), 323–28.

[4] A detailed analysis of the post-revolutionary state-enforced social order is beyond the scope of this article. Briefly, it refers to a non-Western Islamic social order based on the incorporation of Sharia law and the implementation of cultural norms and policies promoting Islamic values, including modesty and piety. A key element includes the compulsory hijab for women and gender segregation in public. This social order distinctly diverges from Western norms and emphasizes a patriarchal structure, reinforcing traditional male dominance in both public and private spheres.

[5] “Bayanat Dar Didar Ba Masolan Nezam” [Statements in the meeting with officials], Khamenei’s website, April 3, 2024.

[6] Mateen Ghaffarian, “Yazidi va Yaminpour Che Chizi Be Hakemiat Miforoshan? ” [What do Yazidi and Yaminpour sell to the government?] Rouydad24, December 16, 2024.

[7] Pre-revolutionary data are extremely hard to come by, but a 1974 survey, for instance, revealed that 75 percent of Iranian men preferred to marry a woman who wore a hijab, indicating a strong preference for it before the revolution.

[8] Mohammad R. Javadi Yeganeh, “Sharheh Yek Challesh Darbareh Hijab” [An explanation of the hijab challenge], February 12, 2017.

[9] “Markaz Pajoheshha: 70 darasad zanan ba tarif sharee hijab, bi hijab hastand” [Majlis Research Center: 70 percent of women, according to Sharia definition, are not veiled], Khabaronline, August 16, 2018.

[10] Goli M. Rezai-Rashti, Golnar Mehran, and Shirin Abdmolaei, eds., Women, Islam and Education in Iran (New York: Routledge, 2019).

[11] Roksana Bahramitash and Hadi Salehi Esfahani, Veiled Employment: Islamism and the Political Economy of Women’s Employment in Iran (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2011).

[12] UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) (Data retrieved from World Bank Gender Data Portal, accessed May 14, 2024).

[13] The author’s estimates are based on raw data from the Iran Statistical Center, Labor Force Survey(s), 1390–1401.

[14] The author’s estimates are based on raw data from the Iran Statistical Center, Higher Education Based on Gender Data, 1350–1401.

[15] World Bank, World Development Indicators (Washington, DC, 2023).

[16] The author’s estimates are based on raw data from the Iran Statistical Center, Labor Force Survey(s), 1390–1401.

[17] Hadi Kahalzadeh, “Civilian Pain without a Significant Political Gain: An Overview of Iran's Welfare System and Economic Sanctions” (Johns Hopkins University, The SIAS Rethinking Iran Initiative: Iran under Sanctions, 2023).

[18] Referencing the Kurdish slogan that the protesters came to adopt as their own.

[19] Robin Wright, “Iran’s Protests Are the First Counter-revolution Led by Women,” The New Yorker, October 9, 2022.

[20] Shahrokni, “Bodies in Revolt.”

[21] “A Comprehensive Report of the First 82 days of Nationwide Protests in Iran” HRANA [Human Rights Activists News Agency], December 8, 2022 [in Persian].

[22] “Statement of the President’s Committee to Investigate the Events of the Fall of 1401,” Entekhab News Agency, March 17, 2024 [in Persian].

[23] “Ersal hodod 1 million tazakor kashfeh hijab barye Khodro ha dar Iran” [Sending about one million hijab detection notices for cars in Iran], Anadolu Agency, June 15, 2023.

[24] The author’s estimates are based on data from public budgets from 2019 and 2021.

[25] This Brief applied the Cost of Basic Needs method to calculate Iran’s poverty rate, which combines the estimated costs of a person’s daily food intake of 2,100 calories.

[26] Sinaiee, “Pezeshkian Says New Hijab Law Cannot Be Enforced.”

Recommended Citation: Kahalzadeh, Hadi. “The Islamic Republic of Iran’s Chastity and Hijab Law and the Weaponization of Women’s Economic Vulnerabilities,” Middle East Brief, no. 162. Crown Center for Middle East Studies, Brandeis University, December 2024.

The opinions and findings expressed in this Brief belong to the authors exclusively and do not reflect those of the Crown Center or Brandeis University.