Golden Passports and Golden Visas in the Gulf

People enjoy a view of the skyline and the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, in January 2021. (AP Photo/Kamran Jebreili)

Middle East Brief No. 163 | February 2025

As borders tighten and mobility becomes increasingly restricted, the Arab Gulf has emerged as an unlikely epicenter for investor migration, with elite Gulf families—foreign residents and citizens alike—driving demand for citizenship-by-investment (CBI) and residency-by-investment (RBI) schemes. Commonly known respectively as “Golden Passport” and “Golden Visa” programs, these initiatives create accelerated legal pathways for third-country nationals to attain citizenship or permanent residency in exchange for foreign investment. [1] Over the last decade, the Gulf—particularly Dubai—has emerged as a critical hub for this market, attracting multinational corporations and hundreds of boutique-investor migration firms. [2] Moreover, all Gulf states—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Saudi Arabia—have introduced their own popular Golden Visa schemes in the past five years, reshaping visa policies and legal frameworks for non-citizens, who constitute approximately half of the region’s population. [3] While the region’s pivotal role in labor migration is well known, its growing influence in investor migration is reshaping global mobility patterns in ways that remain largely unexplored.

Why is the market for passports and visas booming in the Gulf? Why are people in the region investing significant resources to attain citizenship and residency documents from other states—often without intending to migrate? This Brief argues that economically privileged citizens and long-term residents of the Gulf are turning to foreign passports and visas to mitigate legal precariousness and political uncertainty. It identifies three factors fueling demand for Golden Passport and Golden Visa programs: temporary migration laws, exclusionary citizenship laws, and global hierarchies with respect to visa policies. These programs allow families to attain rights in three domains: residency (the right to stay and live in a territory), citizenship (the right to be a citizen), and mobility (the right to cross international borders).

At the heart of this phenomenon are unresolved questions of citizenship and belonging in the Middle East, shaped by legacies of decolonization and state formation and fragmentation, and compounded by regional instability and the global rise in border enforcement. For foreign residents, restrictive citizenship laws and temporary migration policies have created systemic exclusions, fueling the demand for alternative pathways to secure citizenship and residency rights. Meanwhile, as conflicts intensify and climate change looms, many Gulf nationals are also seeking alternative citizenship options to ensure their mobility and security. Examining the region’s demographics, citizenship frameworks, and migration policies reveals how exclusionary policies perpetuate legal precariousness, fostering markets for inclusion that states and private firms eagerly exploit. And while this analysis foregrounds region-specific factors driving demand for Golden passports and visas, it also reflects a broader global trend: States create barriers—through restrictive laws and border controls—and then monetize the rights to bypass them, stratifying citizenship along economic lines.

Citizenship and Residency for Sale

Golden Passport and Visa programs are often perceived as catering exclusively to high-net-worth individuals seeking to evade taxes, engage in illicit activities, or collect multiple passports as “luxury” goods. Ongoing research with families investing in these programs and the firms that cater to them, however, reveals a broader and more complex consumer base. Interviews with firms based in Dubai, Doha, and Riyadh indicate that many upper-middle-class Arab families from states facing political or economic upheaval—such as Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, Palestine, and Iran—are making difficult decisions about how to best use their savings. Many choose to invest in legal status over other resources so as to secure their futures. The CEO of an investor migration firm in Dubai, for example, mentioned that several Caribbean CBI programs are in the same price range as higher education in the United States. He described working with families who prioritize identity documents over college tuition, viewing them as a better long-term investment for their children. [4]

While these individual decisions reflect the pursuit of stability and security, they also highlight the ways in which CBI/RBI programs are reshaping global mobility. These programs may appear to contradict the global trend of tighter border controls, but they are better understood as extensions of those controls. [5] Rather than restricting migration outright, border enforcement increasingly functions as a filtration system, with CBI/RBI programs allowing states greater discretion over whom to exclude or admit. These programs, then, do not undermine border fortification but rather capitalize on it: monetizing access to legal status, reinforcing wealth as a key determinant of inclusion, and commodifying membership and mobility rights.

Formally, there are two different types of programs that confer rights in exchange for investments: “Golden Passports” (CBI programs) and “Golden Visas” (RBI programs). These programs differ in the rights they convey. CBI programs provide passports, allowing individuals to cross international borders and obtain citizenship rights, which are inheritable. RBI programs, by contrast, provide visas that grant residency rights, which are not inheritable and are more easily lost than citizenship rights. Investors can lose their Golden Visa if investment is not maintained, whereas denaturalization (loss of citizenship) is rarer and subject to court challenges. [6]

It is important, however, not to overemphasize these formal differences and rather examine whether a given RBI provides a pathway to citizenship. Some, like Portugal’s RBI program, have minimal residency requirements (fourteen days per year), with investors eligible for naturalization after a specific time period (five years), effectively making it a pathway to Portuguese (and hence EU) citizenship. Others, like the Golden Visas offered by Thailand and the UAE, do not allow investor residents to naturalize, functioning strictly as residency permits regardless of how long investment or residency is maintained.

Both types of programs have proliferated significantly over the past few decades, with nearly half of all countries across the globe now offering some kind of CBI or RBI scheme that exchanges membership (citizenship and residency) rights for investments. [7] States in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have joined this trend, introducing programs to cater to foreign residents based in the region. Over the past five years, as the EU began attempts to curtail its European CBI and RBI programs, countries in the Middle East and North Africa have ramped up their offerings by introducing new programs or restructuring existing ones to attract investors. [8]

Foreign investors can now purchase citizenship outright in Turkey (since 2017), Jordan (since 2018), and Egypt (since 2019). Although Turkey is a relative newcomer to the scene, it now accounts for half of all global passport sales. [9] The region has also seen a rise in RBI programs. All Arab Gulf states now have RBI programs that grant permanent residency rights without the possibility of naturalization. The UAE introduced a “golden visa” in 2019, revising it in 2022 to make the process easier and cheaper. Bahrain has had its own variation of this, launching a “golden visa residency” program in 2022 and then a new “golden license” in exchange for larger-scale investments in 2023. Saudi Arabia launched a “premium residency” scheme in 2023, and Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman have also recently introduced similar programs. These programs are increasingly popular, even though investors in them cannot attain passports and citizenship rights.

To expand on these points; to explain how migration, citizenship, and visa policies are fueling this industry; and to illustrate how CBI and RBI programs are becoming a “market solution” for precarious citizenship, the subsequent sections of this Brief focus on the Arab Gulf region and the barriers its residents face to attaining secure residency, membership rights, and mobility rights.

Temporary Migration Laws

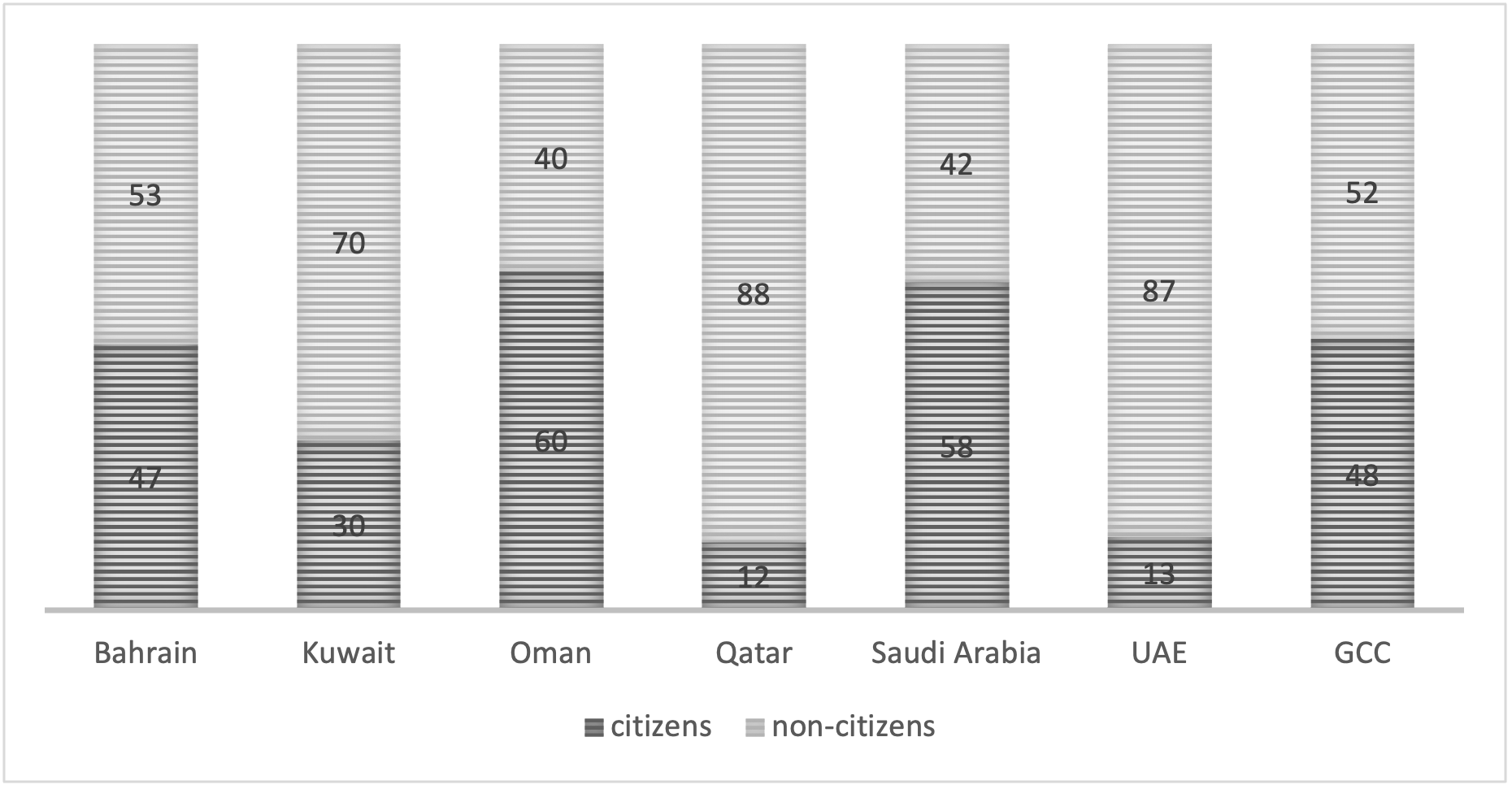

The first factor driving demand for CBI and RBI programs in the Gulf stems from the region’s kafala (guest worker) system and the challenges it creates for people on “temporary” visas for protracted periods. The kafala is a guest-worker system that regulates the rights of non-citizens in the Gulf states, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon. It is a temporary, non-immigrant, employer-based sponsorship system that offers no paths to permanent residency or citizenship. Established during the oil and construction booms of the 1970s, the kafala system facilitated a massive influx of migrants, making non-citizens the majority in four of the six Gulf Cooperation Council states (Figure 1). While this diverse migrant labor force is highly racialized, and segmented by national origin, wage level, and employment sector, officially all non-citizens are classified as “temporary” migrants regardless of their duration of residency in the Gulf or their country of origin. [10] Individuals enter the country as “guest workers” under fixed-term contracts and must leave upon the termination of their employment.

Figure 1: Percentage of citizens and non-citizens in GCC states (estimates 2020– 2022) [11]

In theory, guest-worker programs are designed to meet labor demands without increasing the number of permanent residents. But in practice, migration that begins as temporary quickly takes on a more permanent quality as governments struggle to control settlement. Over the past forty years, the number of foreign residents in the region has risen steadily, with many now joined by spouses and giving birth to second (and even third) generations of immigrants who remain ineligible for permanent residency or citizenship. Unable to become legal permanent residents, permanent migrants are permanently deportable, as their residency authorization is always conditional and circumscribed. This temporary residency authorization is both financially and emotionally costly, leaving people in limbo without the ability to retire or attain citizenship rights in the countries where they have spent most of their lives—or were born.

Thus, a Dubai-based family I spoke with has been settled in the UAE for over four decades with Iranian passports—but holding these passports became a growing liability owing to heightened restrictions tied to UAE residency visa renewals, sanctions, and the visa policies of many states outside the region. To mitigate these challenges, the family pooled its resources to purchase Dominican passports, investing in a new citizenship status in order to continue residing in the UAE—a step that would not have had to be taken if long-term immigrants had pathways to permanent residency rights or if a second generation of immigrants could attain citizenship. This illustrates the financial and logistical burdens of having to turn to the market for identity documents when the lack of legal recognition forces such a choice.

In addition to foreclosing pathways for permanent residency and citizenship rights, the kafala system makes foreign residents overwhelmingly dependent on their national sponsors, exposing them to mobility restrictions as well as human rights abuses. The kafala system externalizes and privatizes migration enforcement to citizens and firms, who act as national sponsors (kafil) responsible for recruiting workers (makful), and are held both legally responsible and financially accountable for all non-citizen residents. This sponsorship arrangement has also historically been used to prevent non-citizens from exiting the territory without the explicit permission of their sponsors. Though there have been reforms to the system, the basic kafala structure remains intact, effectively turning Gulf citizens into “guardians” who mediate state authority by controlling the mobility of migrants.

RBI or “Golden Visa” programs introduced in recent years enable select non-citizens—those who meet minimum income requirements (as must the companies who sponsor them)—to “buy” their way out of some of the most restrictive aspects of the kafala system. These programs allow for greater labor mobility and more freedom to enter and exit the country, as well as making possible the ability to purchase property and the right to own businesses, thereby minimizing sponsors’ overwhelming power over foreign residents. They also authorize longer residency durations (typically ten years instead of one- or two-year visas), reducing the repetitive and costly visa renewal process. In the states that offer them, these RBI programs target high-net-worth and upper-middle-class foreign residents—who would otherwise plan for retirement outside of this region—in order to increase domestic investment, decrease financial outflows, and attract foreign direct investment and skilled talent.

Although Gulf-based RBI programs enhance residency rights for wealthy migrant families, offering them more secure and privileged status compared with lower-income migrants in sectors like construction and domestic work, these programs do not provide a pathway to citizenship. Consequently, “precarious citizenship”—the condition of living in a place for a long period of time without having access to secure membership rights—remains unresolved. [12] This dynamic has established the Gulf as a hub for firms that now promote both local RBI programs and international CBI options, reflecting the continued demand for solutions to challenges of legal status and mobility.

Exclusionary Citizenship Laws

The second factor driving high demand for CBI programs in the Gulf is the exclusionary impact of citizenship laws across the region. Combined with high levels of immigration, these laws create a stratified landscape of precarious citizenship, leaving long-term residents without secure membership rights. In response, many turn to CBI programs outside the region as a solution, obtaining new passports in exchange for financial investment in order to mitigate the challenges posed by restrictive policies.

For example, in an interview with a CBI/RBI firm based in the Gulf in 2023, I learned that after a Houthi strike on Saudi Arabia in 2019, the Saudi government levied new restrictions on Yemeni work authorizations and visas. Yemeni employees of companies considered connected to national security were explicitly banned for security reasons from accessing critical infrastructure. This led the firm to experience a surge in CBI applications from Yemenis who had been based in Saudi Arabia for long periods of time. The firm advised these clients to purchase from lower-cost Caribbean CBI programs, such as St. Lucian and Dominican passports, in order to retain their jobs and continue living in Saudi Arabia legally. This example underscores how exclusionary citizenship laws and geopolitical instability create a market for attaining residency and mobility rights through financial means.

Citizenship laws in the Gulf are patrilineal, requiring individuals to trace their lineage to families present before the formation of a given state. These laws prioritize specific tribes and families, entrench patriarchal structures, and exclude non-Arab minorities, including Persians, South Asians, and East Africans who played a key role in the Gulf’s political economy for centuries prior to the discovery of oil. For example, in the UAE, citizenship eligibility requires families to prove lineage back to the founding Arab tribes present before 1925, a cutoff date chosen to predate the discovery of oil and prevent immigrants from claiming allegiance to the UAE nation for purposes of financial enrichment.

In addition, the patrilineal design of the citizenship laws in all Gulf states prevents women from transferring citizenship to their children or spouses. In 2017, the UAE became the only Gulf state to allow women to transfer citizenship to their children, though only after they reach the age of 18. In practice, informal barriers—such as long delays in the application process and additional requirements like military conscription—have limited the policy’s application there. As a result, most children of Gulf women across the GCC are often on “temporary visas,” treated as foreign residents who carry the nationality of their fathers, and who therefore experience the risk of statelessness, leaving them without legal recognition.

CBI firms based in Dubai, Doha, and Riyadh frequently advise foreign residents to invest both in Gulf-based RBI programs to attain long-term residency and in separate CBI programs to obtain a “better” passport if they hold nationality from a country that is considered a security risk in the Gulf or generally has a low passport ranking. [13] My preliminary interviews suggest that even though Gulf citizens participate in CBI programs, the largest numbers of applicants from the Gulf region are foreign residents from Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Iran. These individuals, who have often lived in the Gulf for years, do not typically intend to migrate elsewhere, but purchase passports so as to more easily navigate increasing restrictions on residency renewals and work authorizations.

Mobility Rights and Passport Rankings

Limited mobility rights are the third factor driving regional demand for CBI and RBI programs in the Gulf, compounded by the geopolitical instability of the broader Middle East. Existing conflicts and the specter of future unrest shape how passports from the region are ranked internationally and influence how people perceive their value in planning for their future. As Aisha, born in Kuwait to Iraqi parents in 1953, told me, “in a second your passport can go from being your most prized possession to your biggest liability.” [14] Like many Iraqis, Aisha’s parents were expelled from Kuwait after the first Gulf War, but she was able to stay, having acquired Kuwaiti citizenship through marriage. And although Aisha and her husband have no intention of leaving Kuwait, they purchased a lavish apartment in Barcelona to attain Spanish citizenship through a residency-by-investment program. The Arab Spring protests in 2011 propelled them to start looking into these programs: “Kuwait seems stable, but you never know, you have to have an exit strategy.” [15] Meanwhile, Ali, an unmarried Saudi Arabian man in his early 40s, opted for the Portuguese residency-by-investment program: “Oil will run out in our lifetime, and when it does, our region will implode. I need to think of my children’s future.” [16] Although Ali does not yet have children, he views his investment in Portuguese citizenship as critical to planning for the post-oil future of his future family.

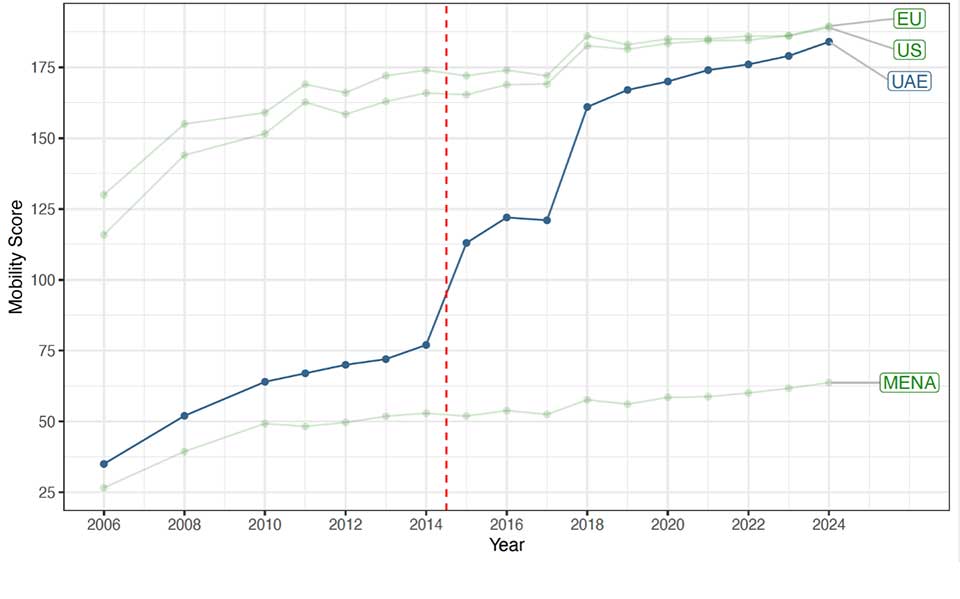

The material effects of citizenship are significant. Aisha’s Kuwaiti passport offers far more mobility than her Iraqi one, and Spanish citizenship provides even more access. Leaving aside significant cross-national differences in membership rights, political stability, and/or standards of living, the international community treats passport holders from the countries in question very differently, illustrating the “global mobility divide.” [17] Thus, Iraqis can travel only to forty-two countries without prior visa approval; Kuwaitis have close to three times that much access (to 111 countries), while Spaniards are able to cross most international borders (177) without any prior security vetting. [18] Figure 2 highlights these disparities, providing the average mobility scores (defined as how many countries allow citizens of a given country or group of countries to enter their territories without a visa) of the MENA region and the UAE compared with those of the United States and EU countries since 2006. [19] The MENA region includes countries that have some of the lowest scores in the world, including Palestine, Yemen, Iraq, and Syria.

Notably, the UAE mobility score first accelerates decisively between 2014-2015, when it signed a Schengen visa waiver granting its citizens visa-free access to the EU— the only state in the region (other than Israel) providing such access. After the UAE successfully signed a Schengen visa waiver, its passport power accelerated exponentially, not only because the Schengen bloc includes access to a large number of states at once, but also because the UAE’s foreign ministry was able to leverage its successful negotiations with the EU to persuade other states to follow suit. This shows the immense influence of states in the Global North in shaping global mobility regimes and how perceptions of which populations are deemed “safe” for travel can spread and be adopted by other states.

Figure 2: Mobility Scores, 2006-2023 [20]

CBI and RBI programs help alleviate inequalities in access to the right to cross international borders, because people “whose birth citizenship is inferior to the global average may seek out a better status without necessarily relocating geographically.” [21] External border controls determine who is authorized to travel internationally, which has ramifications not only for tourism and business, but also with respect to safe passage and the right to flee under duress. For individuals, a second passport offering more visa-free travel is not merely a symbol of prestige or cosmopolitan identity—it can mean the difference between life and death. Those with access to legal travel options can use sanctioned modes of transportation to flee quickly, and are less likely to be forced into human trafficking and smuggling networks.

Although visa waivers do not grant non-citizens the right to settle in foreign lands, access to short-term travel shapes migration patterns, with important implications for access to asylum. Visa controls are the “first line of defense” against unwanted migrants, because the international human rights framework establishes the right to asylum (“safe haven”) but not the right to flee under duress (“safe passage”). [22] This helps explain why families in the Middle East invest significant financial resources in securing just the possibility of movement—not necessarily to migrate, but to ensure the capacity and right to cross international borders quickly and with dignity if needed.

Conclusion

In recent years, CBI/RBI programs have proliferated globally, with the Gulf region emerging as a critical hub for this market. These programs allow individuals to attain residency, membership, and mobility rights in exchange for financial investment. Though marketed as symbols of luxury and exclusivity, these programs are fundamentally shaped by exclusionary citizenship and migration laws that drive demand, offering solutions for people facing legal precariousness in the Gulf.

If the region’s restrictive citizenship and migration laws have produced long-term residents who, despite having lived in the Gulf for years, cannot attain citizenship, then the CBI/RBI market is producing individuals who possess passports but without any real connection to the passport-issuing state. Restrictive citizenship and migration policies create exclusions that in turn generate demand for CBI and RBI programs, thereby producing new forms of citizenship and residency. And CBI and RBI firms have emerged to monetize global differences in citizenship and residency rights so as to capture the demand for secure belonging. This dynamic creates a market in which people “earn” their place as secure legal subjects not via the time they reside in a country or based on their allegiance and connections to a national community, but by being rich enough.

CBI and RBI programs not only reflect regional efforts to navigate legal and economic challenges, but also point to a more complex global dynamic, wherein wealth increasingly serves as a means of overcoming state-imposed barriers. While citizenship and residency have traditionally been markers of national belonging, the proliferation of investment-based pathways highlights a new dynamic, whereby states both create barriers to citizenship and residency and simultaneously offer to lift them for those who can afford to pay. This process deepens existing inequalities and reinforces the stratification of legal status, so that access to rights such as mobility, residency, and citizenship is determined by financial capacity. As the market for CBI and RBI programs grows, it underscores a global trend according to which economic power increasingly dictates the ability to transcend political and legal exclusions, further entrenching the commodification of citizenship itself.

Noora Lori is an associate professor of international relations at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University and a former Goldman Faculty Leave Fellow at the Crown Center.

For more Crown Center publications on topics covered in this Middle East Brief, see “Reconceptualizing Noncitizen Labor Rights in the Persian Gulf,” “On the Third Anniversary of the Abraham Accords,” and “Shut Out of Good Jobs: Contemporary Obstacles to Women’s Employment in MENA.”

Endnotes

[1] Jelena Džankić, The Global Market for Investor Citizenship (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

[2] Philippe Amarante, “Investment Migration Insights” (Henley Global Citizens Report, Q1 2022), Henley & Partners.

[3] As of the latest available demographic data (November 30, 2021), 52 percent of the aggregate population of the GCC states is made up of non-citizens. “Percentage of nationals and non-nationals in Gulf populations (2020)” [National Statistical Institutes], Source: Gulf Labor Markets and Migration (GLMM).

[4] Interview with CEO, Dubai, UAE, November 26, 2023.

[5] Investor citizenship programs tie membership rights to ius pecuniae (the law of money), accelerating naturalization by reducing or entirely eliminating residency requirements for qualified foreign investors. Though early forms of ius pecuniae can be traced to ancient Greece, the contemporary citizenship-by-investment industry emerged in the 1980s with programs launched by Tonga, in 1982, and Saint Kitts and Nevis, in 1984.

[6] Kristin Surak, The Golden Passport: Global Mobility for Millionaires (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2023), pp.14–15.

[7] Among CBI programs, 95 percent of passport sales come from only nine programs: Antigua, Cyprus, Dominica, Grenada, Malta, Saint Kitts, Saint Lucia, Turkey, and Vanuatu. Popular RBI programs are primarily offered by European states, including Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. The fact that these programs will likely be eliminated by the EU in the next few years has only fueled greater demand for them.

[8] Cathrin Schaer, “Middle East Trend for ‘Golden Visa’ Schemes Accelerating,” Deutsche Welle, April 4, 2023.

[9] Surak, The Golden Passport.

[10] Data on the national origin of migrants in the Gulf are sparse, but the available data reveal how diverse this population is. GLMM (Gulf Labour Markets and Migration), “GCC: Some estimates of foreign residents in GCC states by country of citizenship.”

[11] Source: GLMM (Gulf Labour Markets and Migration), “Total population and percentage of nationals and non-nationals in GCC countries.”

[12] Noora Lori, “Statelessness, ‘In-Between’ Statuses, and Precarious Citizenship,” in The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, ed. Ayelet Shachar, Rainer Bauböck, Irene Bloemraad, and Maarten Vink, pp. 743–66 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[13] Interview with employee of CBI firm based in Riyadh, July 31, 2023. Interviews were conducted in Arabic, and participants are referred to by profession or pseudonymously.

[14] Interview with Aisha, Barcelona, Spain, June 29, 2022.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Interview with Ali, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, May 29, 2021.

[17] Steffen Mau, Fabian Gülzau, Lena Laube, and Natascha Zaun, “The Global Mobility Divide: How Visa Policies Have Evolved over Time,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41, 8 (2015): 1192–1213.

[19] The MENA average includes the scores of nineteen countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Israel, Palestine/PLO, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, and Yemen.

[20] Source: Henley & Partners mobility scores.

[21] Dimitry Vladimirovich Kochenov and Kristin Surak, Citizenship and Residence Sales: Rethinking the Boundaries of Belonging (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), p. 3.

[22] Jelena Džankić and Rainer Bauböck, “Mobility without Membership: Do We Need Special Passports for Vulnerable Groups?” (Global Citizenship Observatory (Globalcit), European University Institute, 2021).

Recommended Citation: Lori, Noora. “Golden Passports and Golden Visas in the Gulf,” Middle East Brief, no. 163. Crown Center for Middle East Studies, Brandeis University, February 2025.

The opinions and findings expressed in this Brief belong to the authors exclusively and do not reflect those of the Crown Center or Brandeis University.