China and the Geoeconomic Transformation of the Middle East

Nader Habibi

United Arab Emirates President Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan and Chinese President Xi Jinping shake hands in Beijing on May 30, 2024. (Tingshu Wang/Pool Photo via AP)

Middle East Brief No. 166 | November 2025

Over the last two decades, countries across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have shifted their strategic focus from costly geopolitical rivalries to economic development and regional cooperation, even as multiple conflicts remain unresolved. Episodes such as the Saudi-Iran rapprochement mediated by China and the restrained Arab response to the Gaza War highlight this paradox: Geopolitics persists, but economic imperatives are increasingly decisive in shaping state behavior. This transition reflects both regional pressures—fatigue with prolonged conflicts as well as the urgency of economic reform—and new external opportunities, including the rise of China as a trade and investment partner. This Brief asks how and why this reorientation has taken place, and what role China has played in driving it.

While Beijing remains committed to its long-standing policy of neutrality and non-interference, its growing economic stakes in the region since the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 have motivated it to play a more active, if still limited, diplomatic role in defusing conflicts that might destabilize the region and pose a risk to its oil supplies. [1] For many Middle Eastern states, China has become a reliable economic partner that enables development without political conditions, even as doubts persist about its willingness to serve as a military and security partner.

This Brief argues that China’s emergence as a key economic partner has accelerated the region’s geoeconomic shift. By offering large-scale trade, energy purchases, and infrastructure projects without imposing security alliances or political strings, China has reinforced a regional strategic recalibration that favors economic development over rivalry and confrontation. This shift has not displaced geopolitics but it has rebalanced it, with MENA states turning to geoeconomics as the primary framework for pursuing security and influence amidst U.S. retrenchment. The Brief traces how this dual shift—both regional and Chinese—has unfolded, and what this emerging geoeconomic turn reveals with respect to the future of the Middle East.

China’s Economic Footprint and Middle East Policy

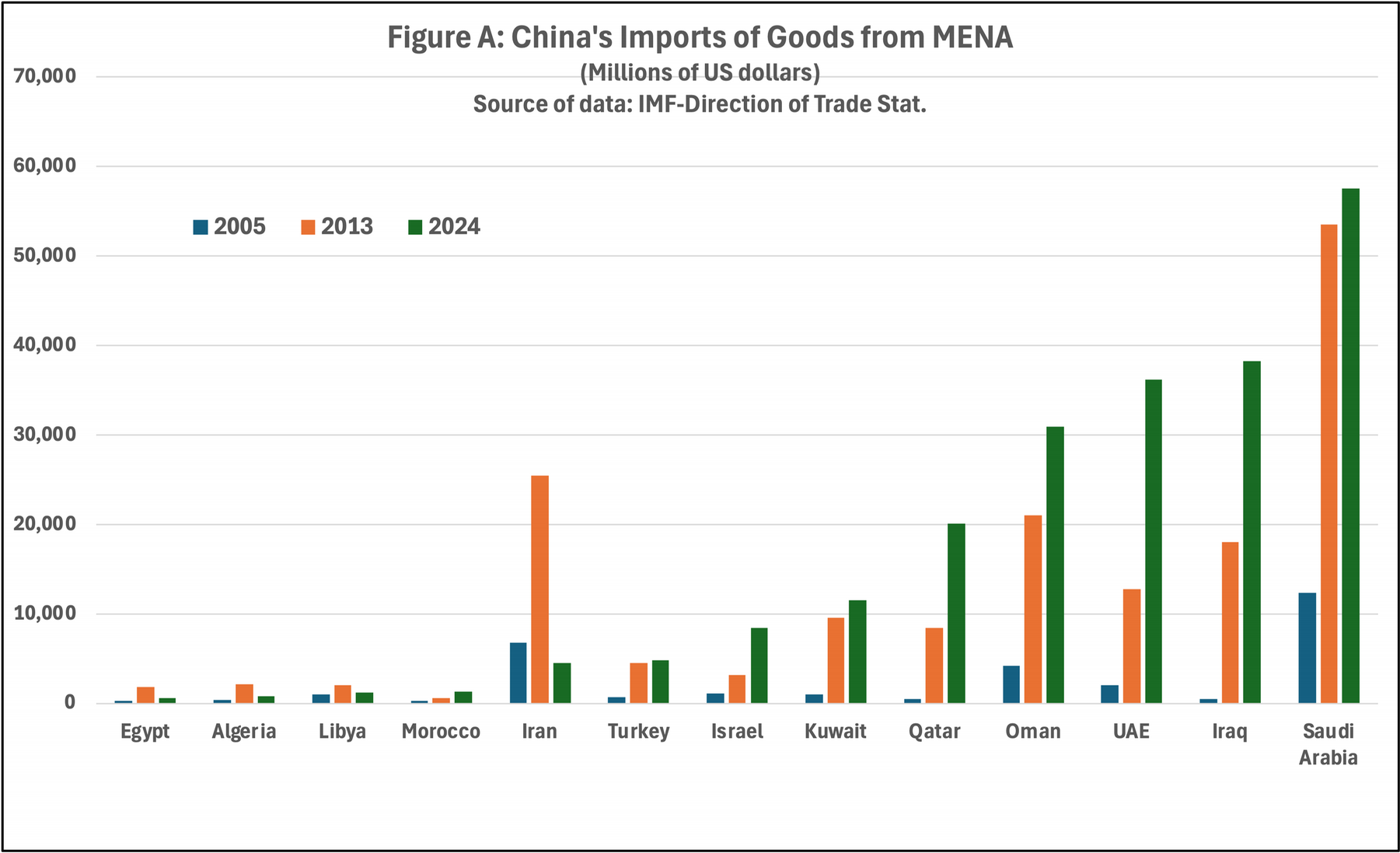

The rise of China has both diversified MENA countries’ external economic ties and restructured the region’s hierarchy of economic partners. Whereas Europe and the United States dominated trade and investment throughout the 20th century, by the start of the 21st century, China had captured much of their market share across the region. This rapid expansion is most visible in energy trade, which makes up a significant portion of China’s total goods imports from MENA countries. As a result, oil exporting countries are the largest import partners of China in the region (Figure A).

Although crude oil imports of European countries have declined because of environmental concerns, and U.S. demand has fallen substantially, China’s crude oil imports increased from 0.68 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2000 to 5.02 mb/d in 2020. [2] By 2023, China was the largest export market for six MENA oil exporters and the second largest for the UAE and Israel (see Table 1). Consequently, many oil-exporting MENA countries now view China as their single most important oil client.

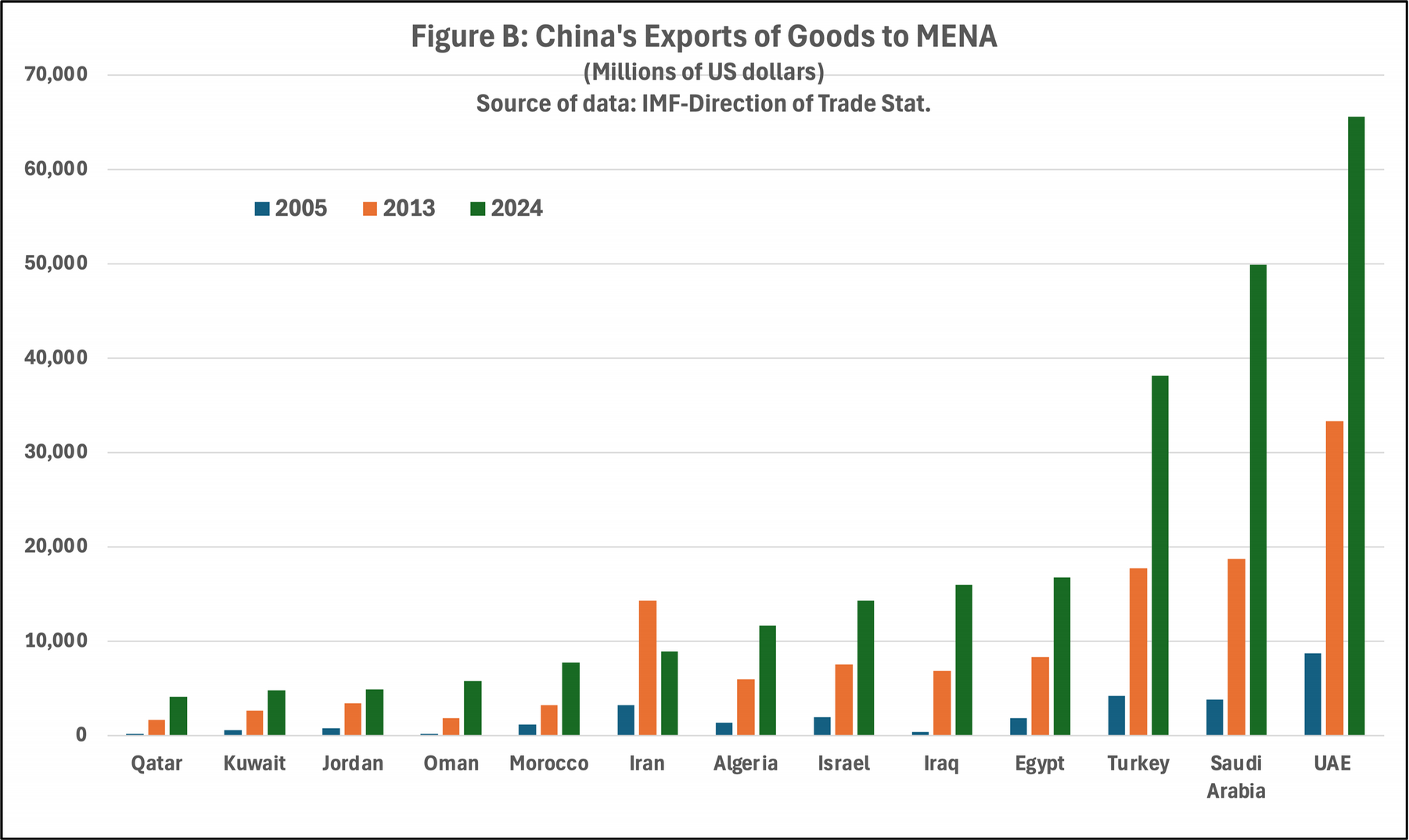

A similar picture emerges when we look at MENA’s imports of goods (Figure B). During the past twenty-five years, China has expanded the range of industrial and manufacturing products it exports, shifting from mostly low- or medium-technology products, such as light consumer electronics, to advanced products, such as 5G mobile telecommunication devices, automobiles, and manufacturing. [3] This has allowed China to capture a substantial share of the MENA import market for both consumer and capital goods.

As shown in Figure B, China’s exports of goods to most MENA countries increased significantly between 2005 and 2024. The only exceptions were Iran and Syria, which were both adversely affected by severe economic sanctions (and a prolonged civil war in Syria). In the decade since the launch of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, China’s exports to MENA countries grew by an average of 5% per year. By 2023, China’s market share of exports ranked either first or second in twelve MENA countries (Table 1).

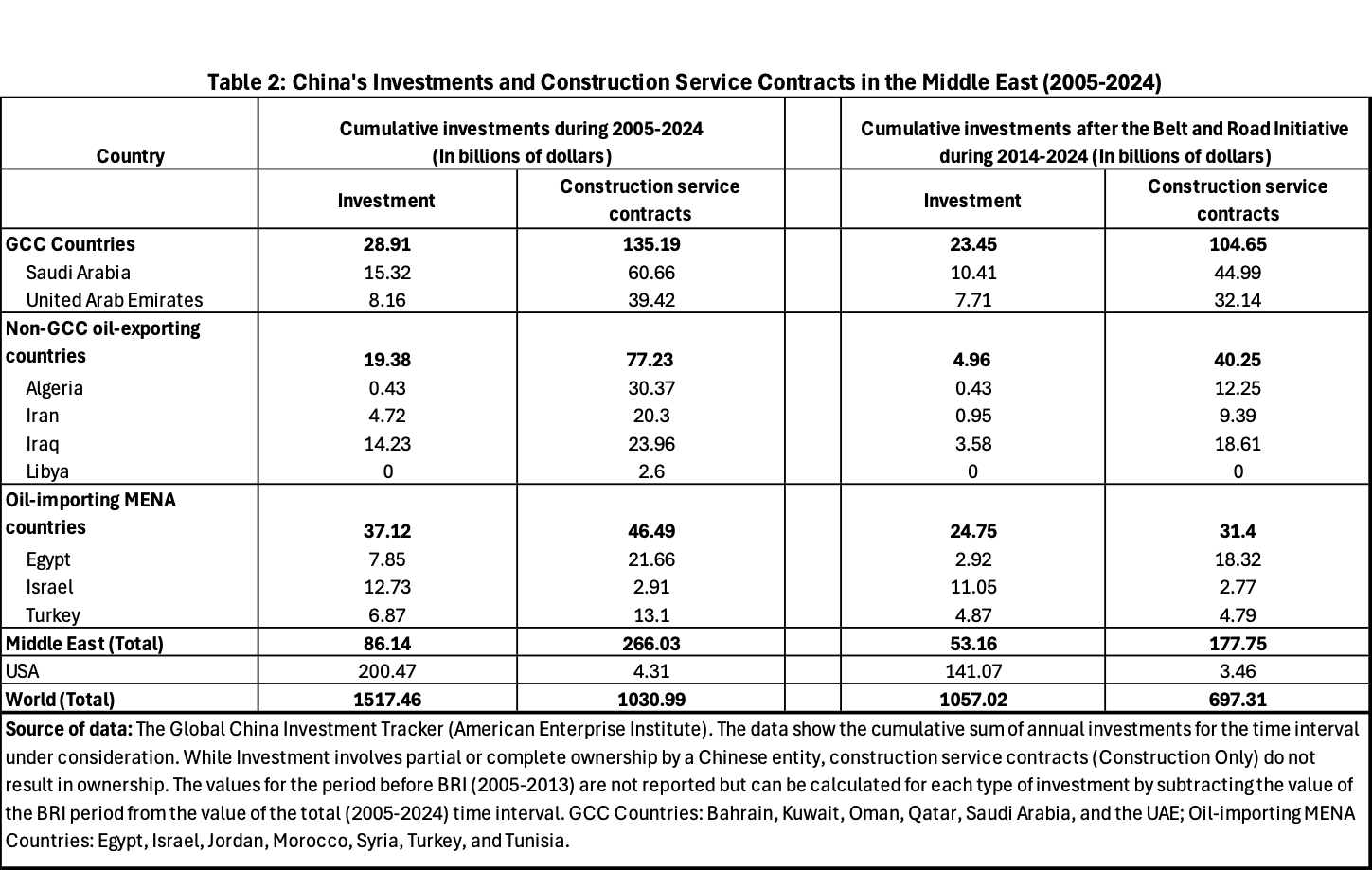

A second important dimension of China’s economic relations with MENA countries is in the area of investments and construction service activities, where China has now overtaken the U.S. and Europe. As Table 2 shows, these activities are divided into a) foreign direct investment and b) construction service contracts awarded to Chinese firms. The difference between these two categories is that investment involves partial or complete ownership, whereas service contracts do not result in any transfer of ownership to Chinese firms.

What stands out is the dominance of construction contracts over investments. For example, between 2005 and 2024, China held more than $135 billion in service contracts with GCC countries alone, compared with less than $30 billion in investments. This pattern contrasts with the comparable data for China’s global footprint, including in the United States, which is dominated by investments rather than construction service contracts.

Two factors help explain the dominance of service contracts in China’s engagement with the Middle East. First, the MENA region is vulnerable to higher risks of political instability and conflict, which have an adverse effect on investment incentives. In these high-risk environments, foreign firms have a preference for signing service contracts rather than making long term investments. Second, many Middle East countries impose severe restrictions on foreign investment, particularly in strategic sectors such as oil and mining.

Overall, this bird’s-eye view of China-MENA economic relations, particularly the dominance of service contracts over investments, suggests more than China’s growing regional footprint. It reveals that MENA states, even those like Israel and those GCC countries that rely on the United States for security, are privileging geoeconomic flexibility and have come to see China as a reliable economic partner that asks for little in return, in contrast to the conditions attached to Western investment and alliances. This status has held even as the United States has tried to curtail China’s economic and technological footprint among its allies. Though some countries have selectively limited or canceled Chinese projects in response to U.S. warnings, the impact of those warnings on the size of their economic relations with China appears to be small or nil: For MENA countries, even close U.S. allies, the opportunities created by the emergence of China as an economic superpower have been too good to ignore. [4] Many MENA countries have adjusted their economic development strategies and foreign policies to take advantage of interactions with China while balancing ties with the United States. [5] This adaptation, and its impact on regional priorities, will be discussed in the next section.

MENA’s Transition to Geoeconomics

The rise of China as a major economic partner not only has had a profound effect on the direction and pace of economic development in the MENA region, but has also contributed to a broader shift in strategic and diplomatic regional priorities. Over the past five years, governments have increasingly come to view economic growth and connectivity as the foundation of national security, a trend that has been called “the transition from geopolitics to geoeconomics.” [6]

For decades the Middle East has been consumed by great power rivalries and conflicts, from the Arab-Israeli conflict to Saudi-Iran proxy wars, as well as by the tensions between Turkey and Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE after the Arab Spring uprisings. These conflicts and rivalries have drained billions of dollars from fiscal budgets that could have been spent on economic development and social welfare across the Middle East. [7] They have also prevented MENA countries from developing strong economic relations with each other and benefiting from regional cooperation. This is evident in the low level of intraregional trade in the MENA region relative to East Asia or the European Union. The Middle East has also fallen behind in the construction of regional transportation infrastructure enabling cross-border land connectivity, such as transit highways and railways. [8]

In recent years, however, we have witnessed a shift in priorities on the part of several major MENA countries toward reduction of regional tensions and improvement of diplomatic and economic relations. Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan initiated a rapprochement with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the UAE in 2019, which has led to improved ties. Even more significantly, Iran and Saudi Arabia restored diplomatic relations in 2023 with the mediation of Iraq and China, which has contributed to a de-escalation of Yemen’s civil war and warmer relations between Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The tensions between Saudi Arabia and the UAE with Qatar, which escalated sharply in 2017, have diminished significantly with the ending of their economic sanctions against Qatar in 2021 and Qatar’s reintegration into the GCC policy coordination. [9]

The most recent test of this new regional strategy came with the Gaza War, which began in October 2023. Despite widespread public anger at Israel’s actions and unconditional military support for Israel on the part of the U.S., Egypt and Saudi Arabia limited their responses to verbal condemnation and moderate diplomatic initiatives to increase international pressure on Israel. [10] The only additional step by Saudi Arabia was to suspend its normalization process with Israel under the Abraham Accords. Neither country scaled back their relations with the United States, nor did other Arab countries. This mild response reflects how wary ruling elites are of allowing diplomatic tensions or renewed conflict to disrupt their large-scale economic development plans—from Egypt’s large infrastructure projects, launched by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in 2014, [11] to Saudi leader Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 [12] megaprojects, worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

Along with these moves to de-escalate regional tensions, Middle Eastern countries are also diversifying their relations with major external powers to support their long-term economic plans. Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Morocco, the UAE, and even Israel have expanded their economic and diplomatic relations with China (and to a lesser degree with Russia) while maintaining their strategic relations with the United States. Saudi Arabia, for example, supported its Vision 2030 program by developing a close cooperation with Russia to stabilize oil markets and earn high oil revenues, while developing strong ties with China for technology and engineering support, which will also help it expand its global economic partners.

Taken together, these developments indicate how MENA countries are recalibrating their geopolitical alliances for the sake of their geoeconomic objectives. While geopolitics has hardly vanished (conflicts in Gaza, Syria, Yemen, and Iran underscore its persistence), it is increasingly being subordinated to economic imperatives.

China’s Role in the Region’s Transition

The region’s transition to geoeconomics reflects several factors, but China has been central in facilitating and accelerating it. Even in the absence of engagement with China, some MENA countries would have likely moved in this direction in the face of geopolitical setbacks and failed regional initiatives. The Saudi leader Mohammed bin Salman, for example, began his informal rule in 2016 with an ambitious plan to confront Iran, escalating several proxy wars in Yemen, Lebanon, and Iraq. After spending large sums on these projects with little success, he shifted Saudi policy toward reduction of hostilities and a path to rapprochement. Similarly, Turkey pursued an interventionist policy toward the Arab world after the Arab Spring, which resulted in high tensions with Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Facing diplomatic isolation, economic hardships, and loss of Arab investment, President Erdoğan abandoned this policy in favor of a rapprochement initiative in 2019. But it was China’s distinctive posture toward the Middle East since 2000 that gave governments both the means and the confidence to pursue de-escalation and development.

The influence of China on the transition of MENA countries toward geoeconomics in recent years has been transmitted via four distinct channels.

Technology, engineering, and construction services: The development vision of Middle Eastern governments includes large-scale construction projects in transportation networks, modern urban designs, advanced technologies, and industrial production. China’s advances in these areas make it now able to export both capital goods and construction services at affordable costs relative to other industrial countries. This availability has made these ambitious projects more feasible, reinforcing MENA governments’ focus on economic and infrastructure development.Furthermore, China’s construction and engineering services have played an important role in facilitating transit and transportation connectivity throughout the region. [13] Projects such as a large international airport in Nasiriyeh, and the planned Development Road linking the Basrah Port in the Persian Gulf to Turkey by means of a highway and railway corridor, [14] pave the way for regional connectivity and create incentives for cooperation and rapprochement among Middle Eastern countries.

China’s avoidance of military partnerships: During the Cold War, the Soviet Union was eager to develop military and security alliances with interested MENA regimes against the United States. China has been reluctant to follow the same path, and has instead focused on economic development. Countries such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Syria looked for opportunities to develop military alliances but have been disappointed by China’s measured sales of weapons systems and transactional security cooperation. [15] China’s reluctance to support MENA countries as a geopolitical and military patron has reduced the value of geopolitical rivalries for these countries and further encouraged them to focus on geoeconomics and economic development.

China’s mediation diplomacy: China’s reliance on MENA countries for a large portion of its total oil imports (46% based on 2023 data) [16] has given rise to a proactive diplomatic and mediation policy to reduce tensions and de-escalate conflicts. Chinese mediation, for example, helped facilitate rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. [17] China also tried to mediate among Palestinian factions in July 2024, in an effort to pave the way to a convergence of Palestinian positions as a means toward a ceasefire and an eventual two-state solution. And during the twelve-day Iran-Israel war of 2025, China initiated an active mediation policy in cooperation with Oman and Egypt.Through these pragmatic efforts to reduce the risk of conflict and instability, China has helped create a more hospitable environment for regional cooperation and connectivity. Even in the case of the Iran-Israel war, the Iran-Saudi rapprochement helped dissuade Iran from retaliating against GCC countries or closing the Strait of Hormuz. [18] China’s mediation indirectly contributed to this positive outcome.

Multipolar institutions (BRI, BRICS, SCO, AIIB): In addition to the Belt and Road Initiative, China has created several other international institutions (primarily in cooperation with Russia) to promote economic and security cooperation. In recent years, China has welcomed Middle Eastern countries into organizations such as BRICS (the bloc of major emerging economies—founded by Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). All of these organizations, with the exception of SCO (which was jointly created by China and Russia for security and anti-terrorism cooperation in Central Asia), are designed to facilitate economic development and global trade. And membership in these China-sponsored institutions has created added incentives for MENA countries to focus on economic goals and try to reduce their geopolitical tensions. Saudi Arabia, for example, has supported many of its Vision 2030 projects in partnership with, or with the participation of, Chinese firms in the context of BRI cooperation. [19] And Egypt has partnered with Chinese firms in the construction of the New Administrative Capital and the Suez Canal Economic Zone, which is being developed to serve as a manufacturing hub for Chinese firms for export to Europe and Africa as well as to the MENA region. [20]

***

At the same time, disappointment with the United States has made China a more attractive partner for Middle Eastern countries. Episodes such as the U.S. abandonment of Hosni Mubarak during the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings [21] and its failure to respond to the 2019 Iranian attack on Saudi oil facilities lowered regional expectations with respect to the benefits of a formal alliance with the U.S. and the value of geopolitical strategies generally. [22] China, by contrast, served as a viable economic alternative and a model of a state-led authoritarian development strategy that resonated with MENA regimes that seek growth without political liberalization. [23] Gulf states in particular have realized that while their small size and small armies limit their capacity to be major geopolitical players, they can be more successful as economic and financial players in the global economy. [24] They have therefore turned to China’s models, and looked to their membership in BRICS, SCO, and other organizations to enhance their geoeconomic influence on the global stage. [25]

U.S. Reaction: From Confrontation to Adaptation

The growing influence of China in the MENA region and the shifting priorities of MENA governments from geopolitics to geoeconomics have not gone unnoticed by the United States. Yet, U.S. policy has struggled to adapt.

The U.S. pushback against China began in the early 2010s; by 2017, the first Trump administration identified China as the most important strategic rival of the United States, and declared the containment of China’s rise a top U.S. geopolitical priority. [26] In this context, the U.S. became more concerned about China’s growing presence in the Middle East and tried to deter its regional allies from getting too close to China. After tolerating the growing economic relations between Israel and China for most of the 2010s, the U.S. warned Israel in 2019 about the role of Chinese firms in the upgrading and maintenance of the Haifa port, and threatened to stop the regular visits of the U.S. Sixth Fleet to that port. [27] This was followed by another strong warning in December 2020 by the U.S. assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs, David Schenker, about Chinese investments in Israel’s high-tech industries. [28] Similar warnings were issued to the UAE, linking its reliance on the Chinese multinational corporation and technology company Huawei to the potential suspension of advanced weapon sales, such as F-35 jet fighters. [29]

Although these warnings compelled some U.S. allies to scale back or modify their economic deals with China, the bilateral relations of all of these countries with China—including Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—have expanded, and remain strong. Recognizing this resilience, the U.S. has begun to adjust its own Middle East policy by acknowledging China’s economic focus and giving more weight to geoeconomic priorities. This new approach began in the last years of the Biden administration. [30]

In some cases, the U.S. has combined security/military agreements with non-defense business deals for U.S. corporations. [31] In order to compete with China, the U.S. has also offered some advanced technologies, which it was reluctant to share in the past, to some Middle Eastern allies. In December 2024, for example, the Biden administration approved a business agreement between Microsoft and the Emirati firm G42, which included the export of advanced AI chips. [32] This deal was approved, however, only after G42, which previously had strong connections with Chinese firms, agreed not to use Chinese high-tech equipment, and to comply with the U.S. demand for safeguards to prevent Chinese access to U.S. AI technology. [33]

The United States has also launched several regional initiatives in response to China’s BRI projects, the most ambitious being the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a proposed rail and shipping network to connect Europe and Asia [34] that will go through the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel. An initial memorandum of understanding was signed in September 2023, but progress has been adversely affected by Arab-Israeli tensions, including the Gaza War, and by the 2025 tariff dispute between India and the U.S.

In light of the unpredictability of U.S. foreign policy under Donald Trump, this geoeconomic approach faces uncertainty. [35] The U.S. is likely to oscillate between aggressively competing with China for business opportunities and selectively trying to contain China’s engagement with some Middle Eastern countries. The emerging geoeconomic opportunities give the U.S. an added incentive to increase its efforts to reduce existing tensions and minimize risks of conflict. The oil-rich GCC countries have welcomed this new approach by offering investment opportunities and pledges of large investments in the United States during Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia and the UAE in April 2025. [36]

Conclusion

Across the Middle East, ruling governments are shifting from militarism and regional rivalries toward infrastructure investment, economic development, and regional cooperation. Under this new approach, several MENA countries are also trying to maintain a balance between security cooperation with the U.S. and economic cooperation with China, and are noticeably hesitant to take sides in the rivalry between the two superpowers.

Several factors explain this shift, which began nearly a decade ago, but one of the most important factors is the growing engagement of MENA countries with China. By expanding its economic and investment relations with MENA countries while avoiding full-scale geopolitical rivalry with the United States, China has increased the appeal of a geoeconomic path. Furthermore, China has intensified its diplomatic and mediation efforts to de-escalate regional tensions. The U.S. reaction to these developments has likewise evolved in ways that further reinforce the region’s shift toward geoeconomics.

This growing focus on economic development and regional cooperation is likely to continue in the coming years, but it faces a number of challenges. The region remains vulnerable to the Israel-Palestine conflict, which has now expanded beyond the Arab world to include direct military confrontations between Iran and Israel. If the global rivalry between China and the U.S. escalates elsewhere, it might also spill into the Middle East, owing to a potential U.S. attempt to disrupt the supply of Middle East oil to China.

The region’s transition to geoeconomic priorities might also be susceptible to domestic unrest and political instability. In some MENA countries, including Egypt, Turkey, and Iraq, large state-sponsored investment projects have not yet resolved key economic problems, such as inequality, low wages, and a high inflation rate. Frustration over these issues might trigger mass protests and urban unrest.

These various risk factors might pause the geoeconomic transition in some MENA countries, but the long-term trend toward prioritizing development over defense spending is likely to persist.

Nader Habibi is Henry J. Leir Professor of the Economics of the Middle East at the Crown Center.

For more Crown publications on topics covered in this Middle East Brief, see “Iran's Eastward Turn to Russia and China,” “Turkey’s Economic Crisis and Erdoğan’s Multiple Rapprochement Initiatives,” and “The Belt and Road Initiative in the Eastern Mediterranean: China’s Relations with Egypt, Turkey, and Israel.”

[1] For more on the impact of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—China’s global infrastructure strategy—on the Middle East, see: Nader Habibi, “The Belt and Road Initiative in the Eastern Mediterranean: China’s Relations with Egypt, Turkey, and Israel,” Middle East Brief, no. 146, Brandeis University, Crown Center for Middle East Studies, February 2022.

[2] U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, “China and the Middle East,” in 2024 Annual Report to Congress of the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2024), p. 356.

[3] Hanwei Huang, Jiandong Ju, and Vivian Yue, “Accounting for the Evolution of China’s Production and Trade Patterns” (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 32415, May 2024).

[4] Jeffrey Reeves, “China’s Expanding Influence in the Middle East and North Africa” (Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, February 24, 2025).

[5] Jennifer Kavanagh, “The United States and China in the Multi-aligned Middle East” (Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, January 9, 2024).[6] Ferid Belhaj, “Africa and the Middle East: The Shift from Geopolitics to Geoeconomics,” (Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief 48/24, October 3, 2024).

[7] Benjamin Petrini and Laith Alajloumi, “Human and Development Costs of the Middle East’s Protracted Conflicts” (International Institute for Strategic Studies, December 2, 2024).

[8] Rabah Arezki et al., Trading Together: Reviving Middle East and North Africa Regional Integration in the Post-Covid Era [Middle East and North Africa Economic Update, October 2020] (Washington, DC: World Bank).

[9] Andrew Mills, “Insight: Business Boom Builds Qatar-Saudi Entente as Gulf Rift Fades,” Reuters, June 13, 2024.

[10] Ali Bagheri Dolatabadi and Ayoob Damyar, “Arab States’ Positions on the Gaza War (2023–2024): A Historical Analysis of the Decline of Arab Nationalism,” Quarterly Journal of West Asia Political Research 1, no. 2 (March 2025).

[11] President el-Sisi adopted a very cautious and conservative response to make sure the crisis in Gaza did not disrupt Egypt’s ongoing megaprojects. For more details, see Hesham Sallam, “The Autocrat-in-Training: The Sisi Regime at 10,” Journal of Democracy 35, no. 1 (January 2024): 87–101.

[12] Nader Habibi, “Implementing Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030: An Interim Balance Sheet,” Middle East Brief, no. 127, Brandeis University, Crown Center for Middle East Studies, April 2019.

[13] Nicholas Lyall, “China–Middle East Connectivity: Can Chinese Projects Close Economic Gap?” (New Line Institute, April 17, 2025).

[14] Sinan Mahmoud, “Iraq Woos China for Transport Project Linking Asia to Europe,” The National, June 1, 2023.

[15] Jon Hoffman, “Aimless Rivalry: The Futility of US-China Competition in the Middle East” (Cato Institute, Policy Analysis No. 1000, July 10, 2025).

[16] Oceana Zhou, “CHINA DATA: Russian crude imports up 24% to 2.15 mil b/d in 2023”, (S&P Global, January 22, 2024).[17] Najla Alzarooni, “From the Gulf to the Middle East: The Expansion of China’s Mediation Diplomacy,” in Decoding the Chessboard of Asian Geopolitics: Asian Powerplay in South Asia, Central Asia, and West Asia, ed. Debasish Nandy and Monojit Das (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2025), pp. 387–402.

[18] Nader Habibi, “Two Years In, Iran-Saudi Rapprochement Proves Resilient” (Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, July 8, 2025).

[19] Chen Juan, Shu Meng, and Wen Shaobiao, “Aligning China’s Belt and Road Initiative with Saudi Arabia’s 2030 Vision: Opportunities and Challenges,” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 4, no. 3 (Fall 2018): 363–79, and Dongmei Chen, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Saudi Vision 2030: A Review of the Partnership for Sustainability” (King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, May 2021).

[20] Mohamed Soliman, Mahmoud Ahmed Mohamed and Jun Zhao. “The Multiple Roles of Egypt in China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative,’” Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 13, no. 3 (June 2019): 428–44.

[21] Bülent Aras and Richard Falk, “Authoritarian ‘Geopolitics’ of Survival in the Arab Spring," Third World Quarterly 36, no. 2 (2015): 322–36.

[22] Md. Muddassir Quamar, “Saudi Arabia’s Strategic Partnership with the United States: Fraying at the Margins?” Strategic Analysis 46, no. 3 (June 2022): 293–306, and Ghada Ahmed Abdel Aziz, “The Saudi–US Alliance Challenges and Resilience, 2011: 2019,” Review of Economics and Political Science 8, no. 3 (July 2023): 208–25.

[23] Jon B. Alterman, “The ‘China Model’ in the Middle East,” Survival 66, no. 2 (2024), 75–98.

[24] Adel Abdel Ghafar, “Between Geopolitics and Geoeconomics: The Growing Role of Gulf States in the Eastern Mediterranean” (Istituto Affari Internazionali, IAI Papers 21, no. 6, February 2021), 1–25.

[25] Nicholas Lyall, “China’s Approach on Saudi Arabia and the UAE” (New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, Policy Report, July 2025).

[26] The White House, “National Security Strategy of the United States of America” (December 2017).

[27] Arie Egozi, “US Presses Israel on Haifa Port amid China Espionage Concerns: Sources,” Breaking Defense, October 5, 2021.

[28] “US Warns Chinese Investments in Israeli Tech Could Pose a Security Threat,” Times of Israel, December 22, 2020.

[29] Grunt Rumley, “Unpacking the UAE F-35 Negotiations”, Policy Watch 3578, (The Washington Institute, February 15, 2022).[30] Brian Katulis, “US Policy in the Middle East: A Report Card” (Middle East Institute, May 8, 2025).

[31] Frank Holmes, “U.S. Defense and AI Companies Poised to Dominate Middle East Spending Wave,” Forbes, May 19, 2025.

[32] “US Clears Export of Advanced AI Chips to UAE under Microsoft Deal, Axios Says,” Reuters, December 8, 2024.

[33] John Sakellariadis, “Commerce-Backed Deal with Emirati AI Giant Sets Off Alarm Bells in Congress,” Politico, May, 24, 2024.

[34] Arash Reisinezhad and Arsham Reisinezhad, “The Corridor War in the Middle East,” Middle East Policy 32, Issue 3 (Fall 2025): 91–108.

[35] Katulis, “US Policy in the Middle East: A Report Card.”

[36] Holmes, “U.S. Defense and AI Companies Poised to Dominate Middle East Spending Wave.”

Recommended Citation: Habibi, Nader. “China and the Geoeconomic Transformation of the Middle East” Middle East Brief, no. 166. Crown Center for Middle East Studies, Brandeis University, November 2025.

The opinions and findings expressed in this Brief belong to the authors exclusively and do not reflect those of the Crown Center or Brandeis University.