Professors Stephen Cecchetti and Aldo Musacchio spoke March 18 at an event sponsored by the Perlmutter Institute for Global Business Leadership.

Analysts believe Russia’s economy could shrink by 20 percent as a result of the financial sanctions imposed by the West. Whether that’s enough to convince Russian President Vladimir Putin to end the war in Ukraine remains unclear.

On March 18, Prof. Stephen Cecchetti told a virtual audience that it’s still too early to determine the ultimate success or failure of the sanctions because both sides are engaged in a back-and-forth economic battle.

“Sanctions are an arms race,” said Cecchetti, the Rosen Family Chair in International Finance at Brandeis International Business School. “The idea is that you impose sanctions and the target spends some time trying to figure out how to evade them.”

If significant loopholes within the sanctions exist, Russia can be counted on to exploit them. And that’s when the United States and its allies must be prepared to impose appropriate countermeasures, said Cecchetti.

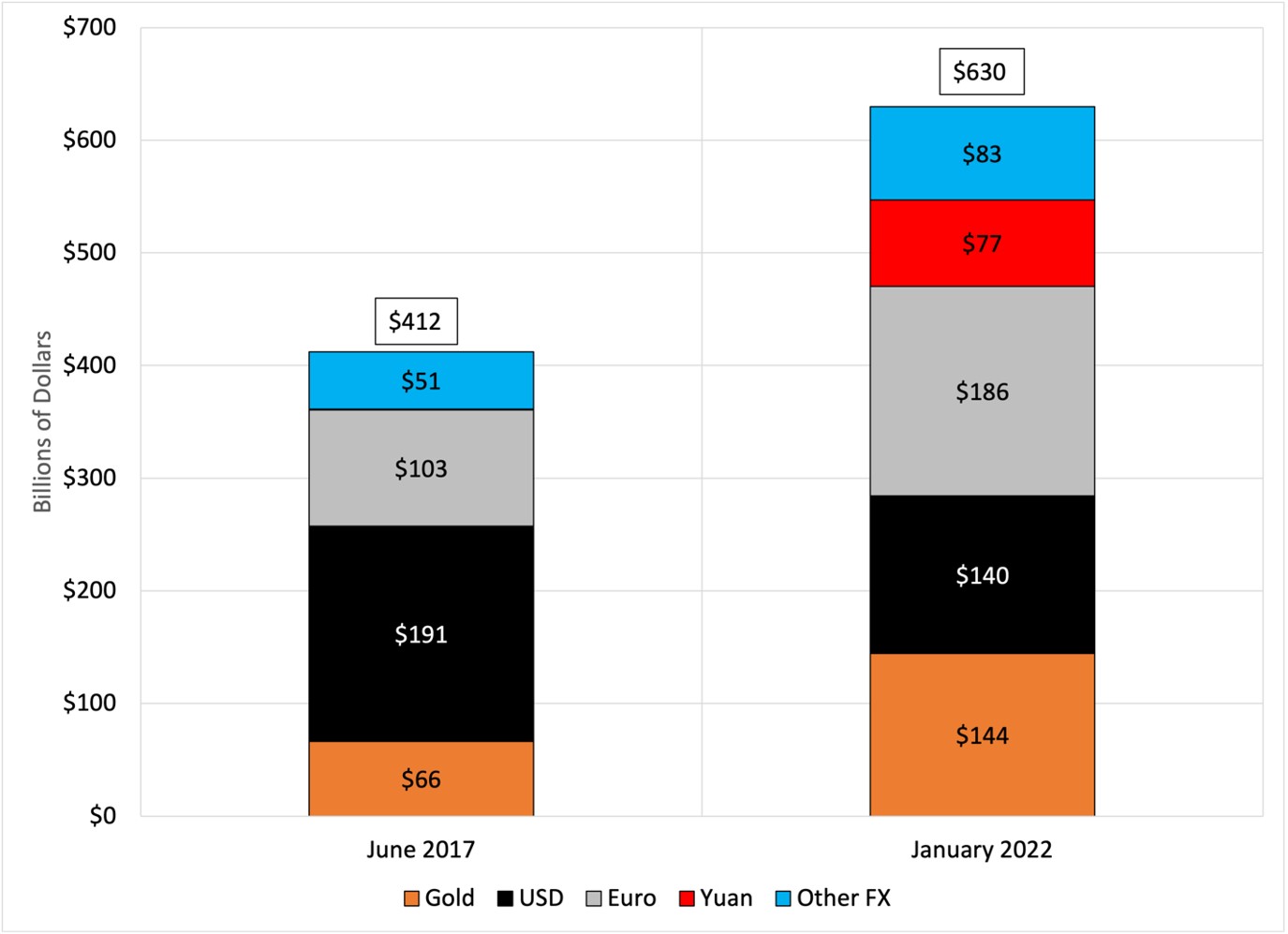

Russia's international reserves (billions of dollars).

Additionally, the United States and European Union have blocked Russia’s central bank from accessing its international reserves. As a result, Cecchetti said Russia will be unable to spend its foreign cash stockpile to prop up the value of ruble, fund the military operation in Ukraine, or purchase imported goods and services.

Cecchetti also discussed the decision to exclude most Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) — the global messaging network used by financial institutions that Cecchetti called “Gmail for banks.”

The move “makes it almost impossible for (Russia) to execute cross-border transactions,” he said.

Cecchetti said widespread participation is necessary for sanctions to be successful.

When sanctions fail, it’s typically because a third-party company (or companies) engage in economic activity with the target country. A strategically important but controversial countermeasure to this type of behavior is the imposition of “secondary sanctions” on the third-party companies, Cecchetti explained.

“(Secondary sanctions) are imposed quite effectively in the case of Iran, for instance, and to some extent Venezuela and certainly with North Korea,” said Cecchetti. “They are very controversial because they're extraterritorial — one country is punishing companies somewhere else for doing something that they don’t like in yet a third place.”

In the context of Russia, Cecchetti said the United States is now facing a critical decision about whether secondary sanctions should be levied against Chinese firms and banks, including the People’s Bank of China, China’s central bank.

“We’re going to find out pretty soon whether or not the U.S. is willing to do that,” said Cecchetti.

Soviet-era oil and gas pipelines.

If there’s a glaring weakness in the West’s sanctions strategy, look no further than the Russian oil and gas pipelines supplying much of Europe.

Musacchio estimates that Russia is receiving roughly $700 million every day thanks to Europe’s energy dependence, even as the war in Ukraine escalates.

“This is where I feel the Russians have outsmarted the West for decades now,” said Musacchio, director of both the Perlmutter Institute and the Master of Business Administration (MBA) program. “If you look at all the sanctions, the Europeans have resisted at all costs any of the bans on the oil and gas sector.”

Musacchio said Russia’s state-run oil and gas companies are highly profitable, and a strategically important revenue source for Putin’s government.

Unfortunately for the West, targeting this sector with sanctions would also force Europe to pay a steep economic price. Musacchio said Russia provides between 30 to 40 percent of the continent’s total gas supply, while also serving as a key oil supplier to Germany and many countries in Eastern Europe.

“The fact that we cannot cut off this flow of money from Europe makes it very hard for the sanctions to actually bite,” said Musacchio.

Even the seizure of yachts, real estate holdings and other foreign assets from Russian oligarchs may do little to end the war.

Before invading Ukraine, Putin met with a large group of oligarchs — most likely to let them know what was coming, said Musacchio.

“A lot of these people took measures to prevent the sanctions from actually affecting them,” said Musacchio. “Some of them moved their yachts to the Seychelles and places that don't have extradition agreements with the West, or places that are just going to protect their assets. They probably moved a lot of their money out of the obvious places.”

Another factor is political power. Despite their fantastic wealth, Russia’s economic elite have held little political influence since the 1990s. Putin has systematically “realigned” the Russian oligarchy in recent decades to the point where nearly all political power and decision-making stems from him, said Musacchio.

“It's hard to think that the political and economic elites have the political power and the capacity to topple him,” said Musacchio.

Featured Stories

News Categories

@BrandeisBusiness Instagram

View this profile on InstagramBrandeis Intl. Business School (@brandeisbusiness) • Instagram photos and videos