Buffalo Bill Dime Novels

June 4, 2014

Description by Max Goldberg, Archives and Special Collections Reference Assistant

The Dime Novel collection at Brandeis includes more than a thousand items characteristic of America's turn towards mass market publishing at the turn of the last century. First introduced in 1860 by the firm Beadle & Adams, the dime novel exploited cheap printing, newly efficient distribution and a broader reading public hungry for sensational yarns involving detectives, cowboys and romantic heroines. Built with major donations by Edward G. Levy, Edward T. LeBlanc and former Special Collections librarian Victor Berch (MA ’66), the Brandeis collection offers valuable material resources for students of popular culture and genre literature.

The Dime Novel collection at Brandeis includes more than a thousand items characteristic of America's turn towards mass market publishing at the turn of the last century. First introduced in 1860 by the firm Beadle & Adams, the dime novel exploited cheap printing, newly efficient distribution and a broader reading public hungry for sensational yarns involving detectives, cowboys and romantic heroines. Built with major donations by Edward G. Levy, Edward T. LeBlanc and former Special Collections librarian Victor Berch (MA ’66), the Brandeis collection offers valuable material resources for students of popular culture and genre literature.

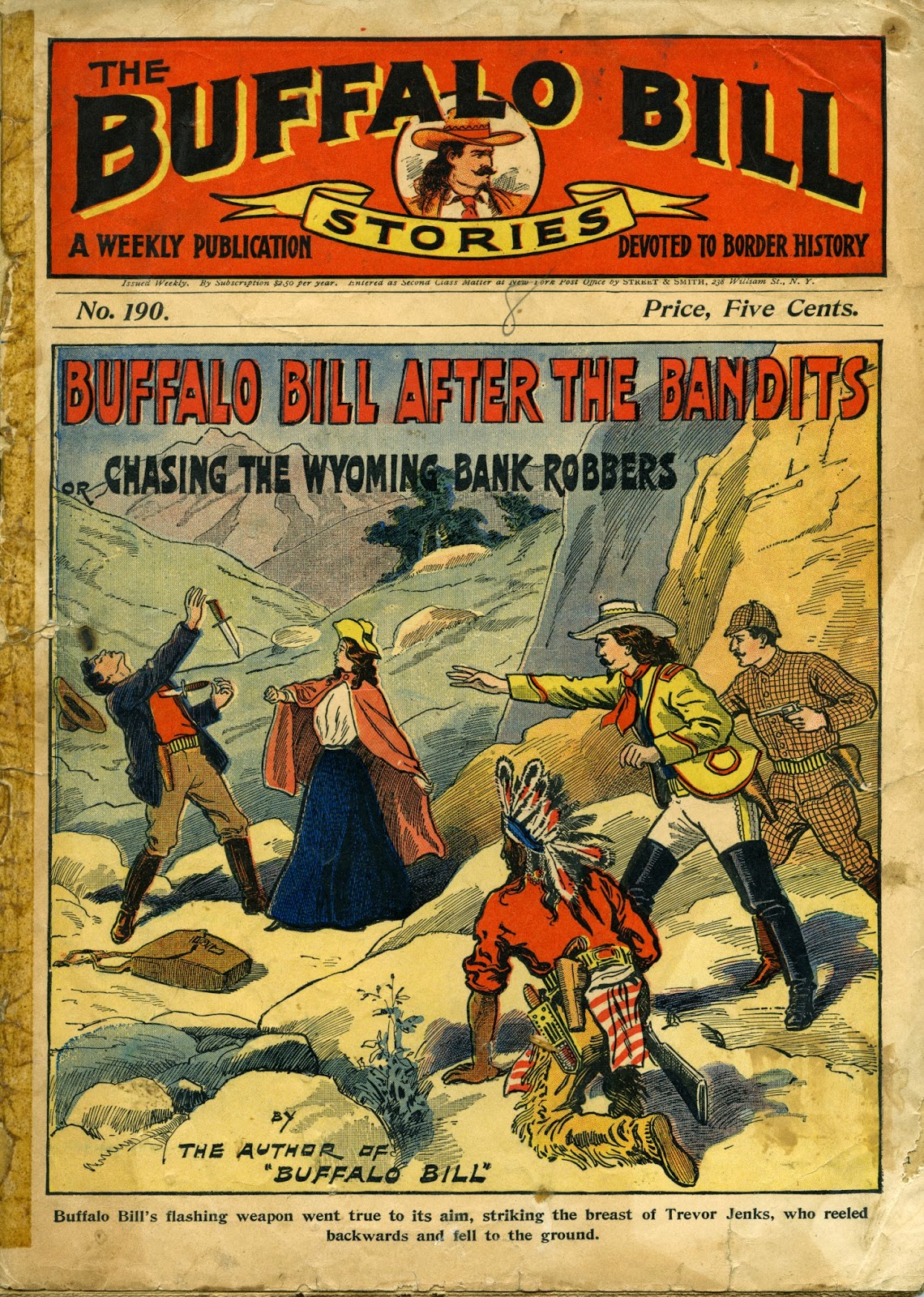

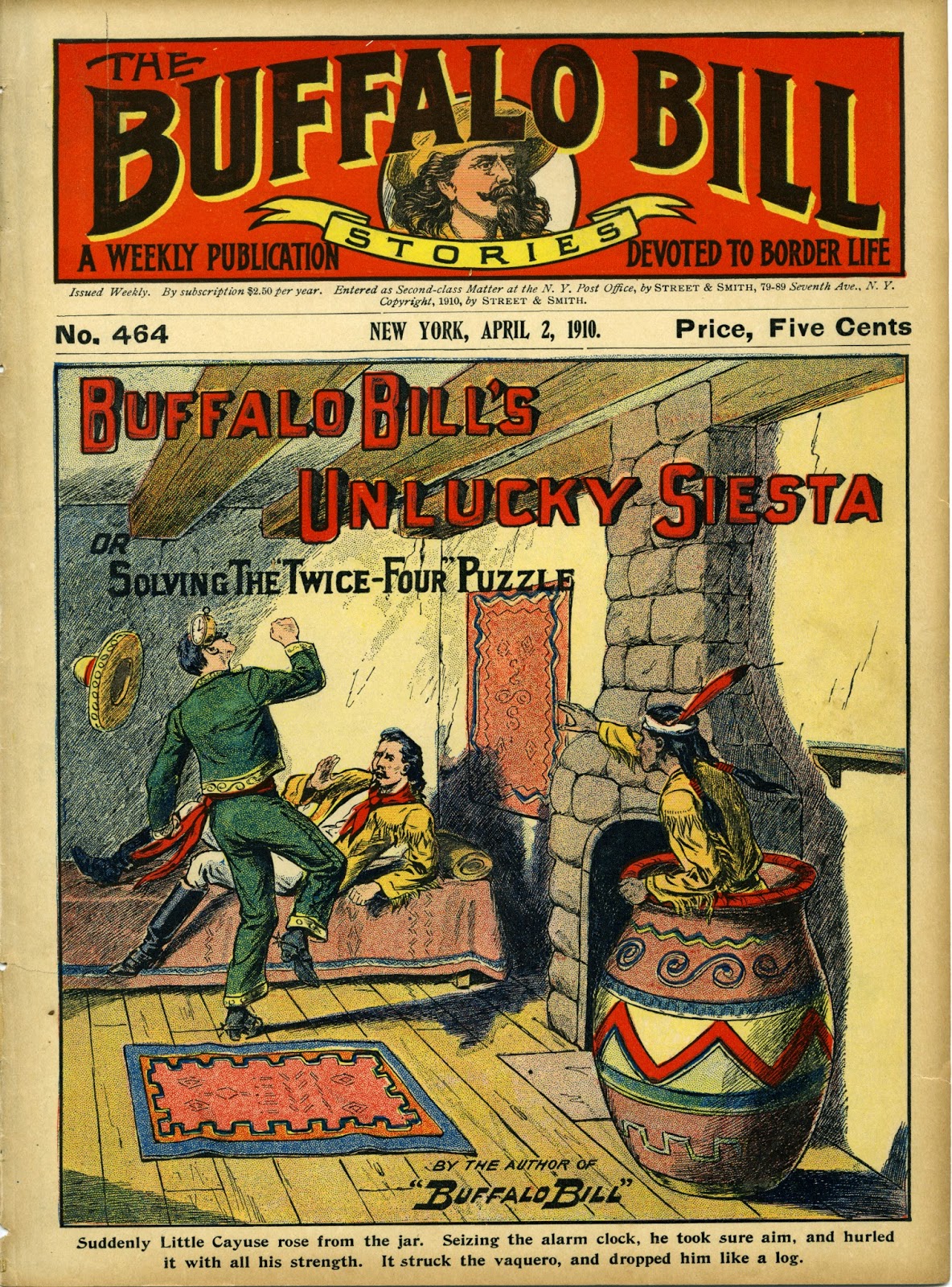

The numbers of "The Buffalo Bill Stories," for instance, present the reader with a wellspring of enduring iconography and storytelling tropes. Buffalo Bill (né William Cody) was already a legendary figure and bona fide international celebrity by the time these books were published. After stints working as a cattle driver, teamster, innkeeper and military scout, Cody found his calling as a guide to wealthy easterners desiring a "true" experience of the west. He caught the eye of Ned Buntline, an early dime novel impresario who prevailed upon Cody to play himself in a Chicago stage melodrama called "Scouts of the Prairie" in 1873. Cody soon formed his own touring company, and from here it was a few short steps to "Buffalo Bill's Wild West," a hugely popular pageant of historical melodrama and spectacular displays of marksmanship, riding and other feats of derring-do. Prominent westerner Larry McMurtry contends that:

William F. Cody's "invention" begun with a nudge from Ned Buntline and developed with the help of his long-suffering assistants Nate Salsbury and John Burke, was to take the kind of pageants current in Barnum and others and focus them on the West, the winning of which thus came to seem a triumphant national venture. The audiences not only bought it, they loved it, at least as long as Cody was there himself, on his white horse. What his career proved is that there is almost no limit to how far a man can go in America if he looks good on a horse; and Buffalo Bill looked so good on a horse that it was almost as if the animal had been created just for him t ride. [1]

One person taking careful note was Theodore Roosevelt, who would eventually nick Cody's "Rough Riders" brand for his own run at the White House. Authenticity was a key element of the Wild West's publicity machine: eastern audiences could see skirmishes re-enacted by historical actors well before the actual conflicts had been settled. The cycle of history, performance and myth could become quite dizzying, as when Cody interrupted a Wild West tour to join up with the Fifth Cavalry at first news of Custer's Last Stand. He killed a Cheyenne warrior during the engagement, shrewdly working the event into his act within a few months and even going so far as to invite the very Indian warriors with whom he previously battled to join his Wild West show.

One person taking careful note was Theodore Roosevelt, who would eventually nick Cody's "Rough Riders" brand for his own run at the White House. Authenticity was a key element of the Wild West's publicity machine: eastern audiences could see skirmishes re-enacted by historical actors well before the actual conflicts had been settled. The cycle of history, performance and myth could become quite dizzying, as when Cody interrupted a Wild West tour to join up with the Fifth Cavalry at first news of Custer's Last Stand. He killed a Cheyenne warrior during the engagement, shrewdly working the event into his act within a few months and even going so far as to invite the very Indian warriors with whom he previously battled to join his Wild West show.

Given this backdrop, it's hardly surprising that many of the issues of "The Buffalo Bill Stories" in the Brandeis Dime Novel Collection should come with a prefatory note admonishing the reader to "Beware of Wild West imitations of the Buffalo Bill stories. They are about fictitious characters. The Buffalo Bill weekly is the only weekly containing the adventures of Buffalo Bill, (Col. W.F. Cody), who is known all over the world as the king of the scouts."

Given this backdrop, it's hardly surprising that many of the issues of "The Buffalo Bill Stories" in the Brandeis Dime Novel Collection should come with a prefatory note admonishing the reader to "Beware of Wild West imitations of the Buffalo Bill stories. They are about fictitious characters. The Buffalo Bill weekly is the only weekly containing the adventures of Buffalo Bill, (Col. W.F. Cody), who is known all over the world as the king of the scouts."

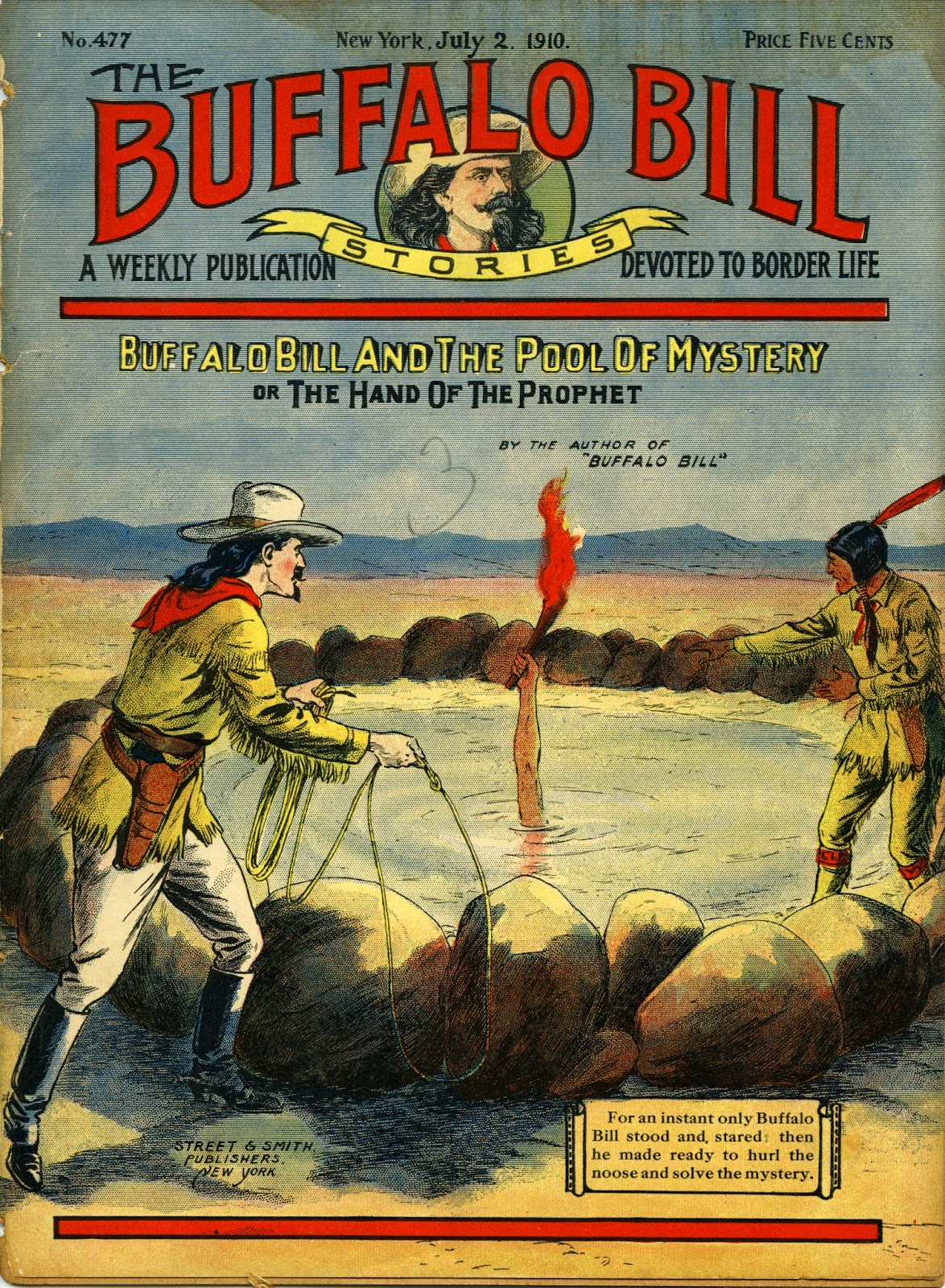

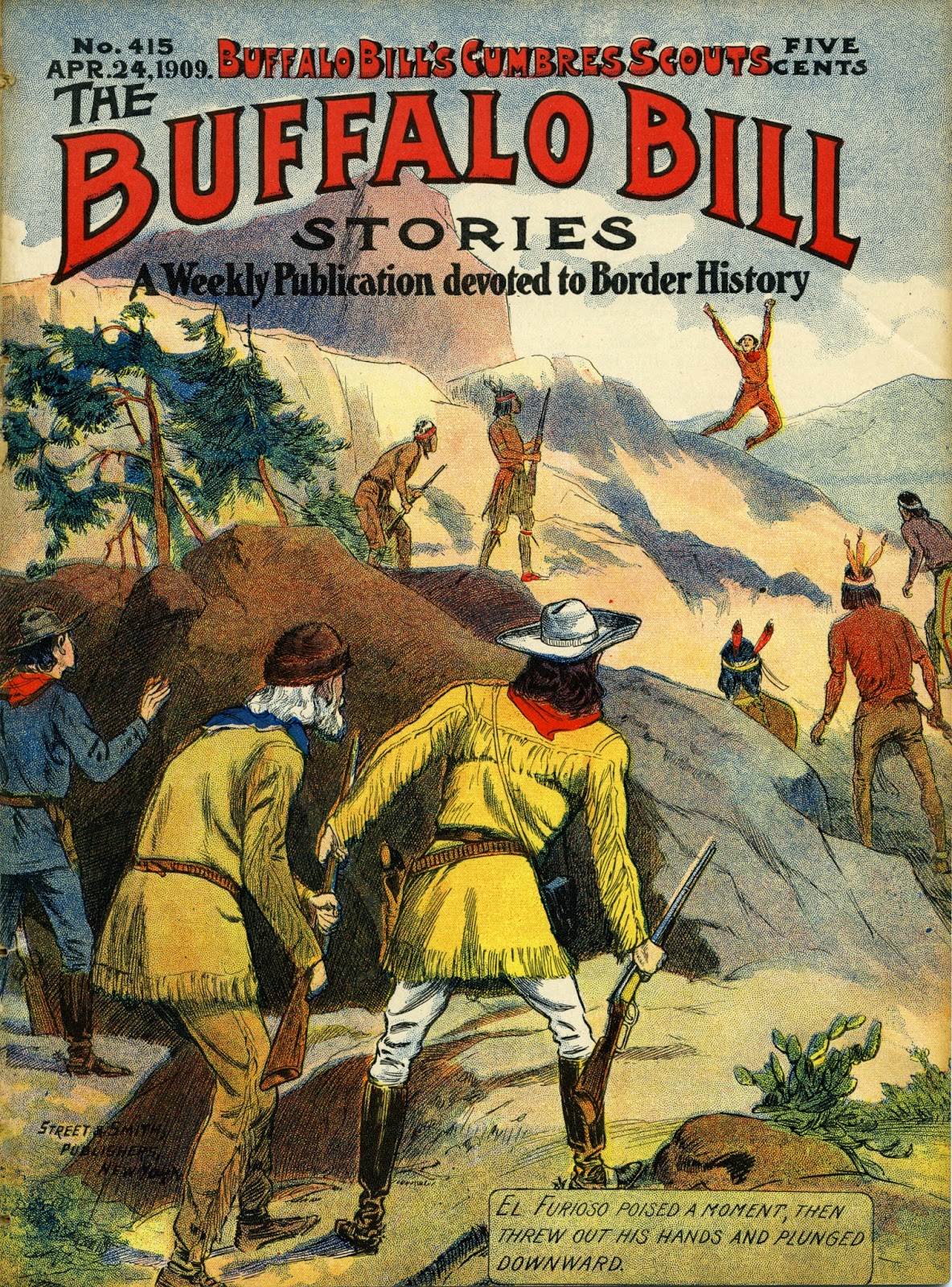

The air of realism extends to the back matter included after the stories: how-to guides of dubious practicality to the largely urban readership ("How to Tie a Wire") and pseudo-ethnographic excursions ("The False-Face Dance"). The books also follow the example of the Wild West plays in offering dual titles: for instance, "Buffalo Bill's Cumbres Scouts: or the Wild Pigs Corralled." The economic logic here is obvious enough (why settle for trying to hook the audience with one title when you can use two?), but André Breton himself would have been hard-pressed to best the likes of "Buffalo Bill and the Pool of Mystery: or the Hand of the Prophet."

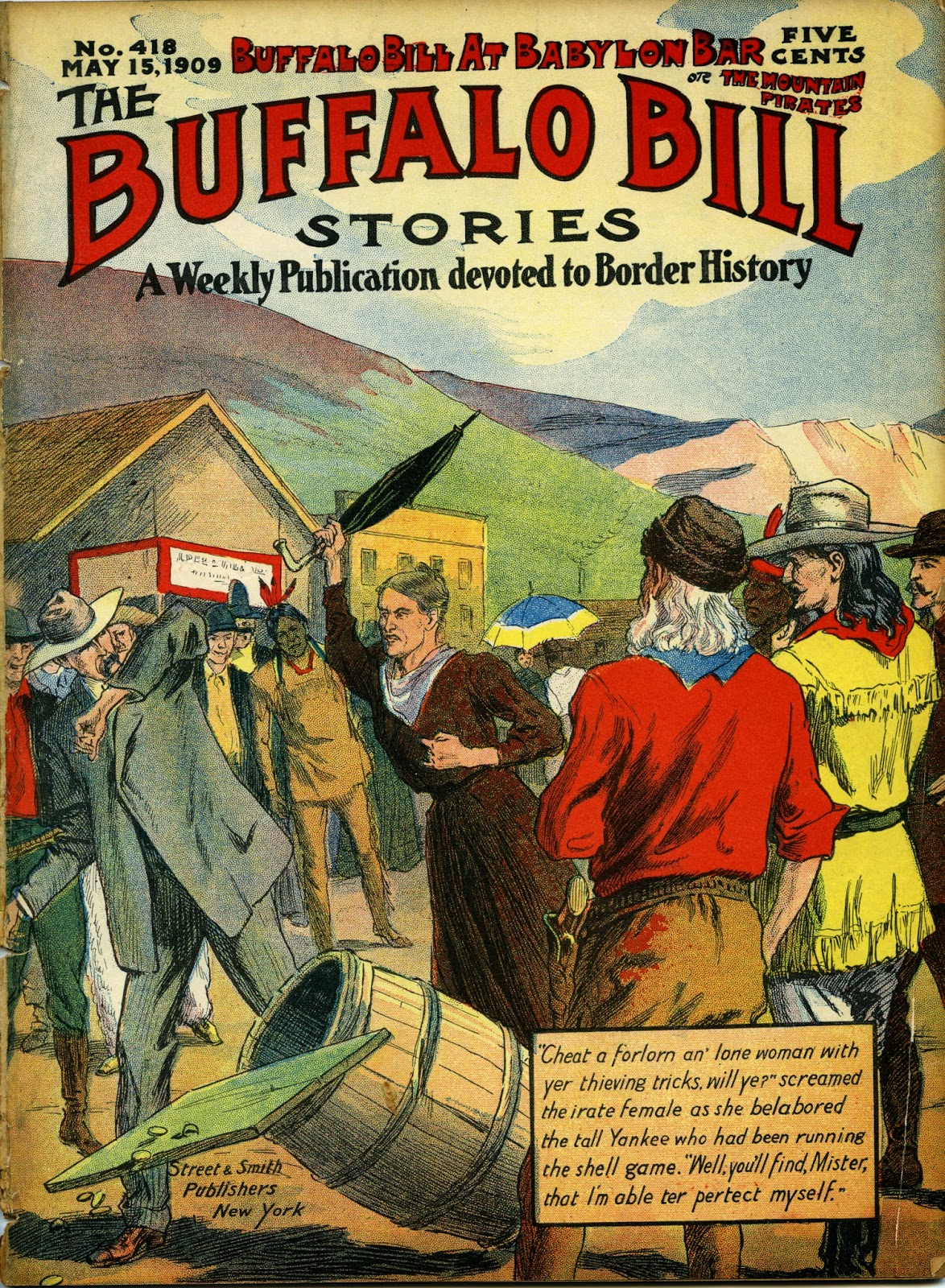

If the dime novels were somewhat late arrivals to the burgeoning Wild West industry, their cover illustrations and dialogue-rich scenarios provide a crucial link between the touring circuit and the coming nickelodeon boom. With its emphasis on action and heroic figures, the western genre proved natural fodder for the new medium — even as early westerns like "The Great Train Robbery" (1903) were filmed no further west than New Jersey. In the cover illustrations of "The Buffalo Bill Stories" we find the basic repertoire of gestures and compositional framings familiar from thousands of western movies. Cody's body is invariably outstretched, and the corresponding text boxes offer a complimentary burst of excitable talk (" 'Up with that left hand of yours, quick, Death Notch Dick, or my bullet hunts your heart' cried Buffalo Bill"). Even in those illustrations not depicting daring rescues, action remains paramount. Take the cover of No. 418 (May 15, 1909), in which the only weapon being brandished is the umbrella of an "irate female." In the foreground of the image, a barrel has been knocked over on its side. It appears mid-fall, a photographic freeze of action that seems to hasten the retreat of the “thieving Yankee" as an assembled crowd watches on.

If the dime novels were somewhat late arrivals to the burgeoning Wild West industry, their cover illustrations and dialogue-rich scenarios provide a crucial link between the touring circuit and the coming nickelodeon boom. With its emphasis on action and heroic figures, the western genre proved natural fodder for the new medium — even as early westerns like "The Great Train Robbery" (1903) were filmed no further west than New Jersey. In the cover illustrations of "The Buffalo Bill Stories" we find the basic repertoire of gestures and compositional framings familiar from thousands of western movies. Cody's body is invariably outstretched, and the corresponding text boxes offer a complimentary burst of excitable talk (" 'Up with that left hand of yours, quick, Death Notch Dick, or my bullet hunts your heart' cried Buffalo Bill"). Even in those illustrations not depicting daring rescues, action remains paramount. Take the cover of No. 418 (May 15, 1909), in which the only weapon being brandished is the umbrella of an "irate female." In the foreground of the image, a barrel has been knocked over on its side. It appears mid-fall, a photographic freeze of action that seems to hasten the retreat of the “thieving Yankee" as an assembled crowd watches on.

Cody himself would find himself on the sidelines when the film medium encroached upon his territory. His 1913 film epic, "The Indian Wars," was by all accounts a flop, and Cody eventually fell back upon a series of ill-advised business ventures and cut-rate performances. So too did the dime novels eventually give way to the neatly packaged narratives available via radio and cinema. But even with their all-but-inevitable obsolescence, the issues of "The Buffalo Bill Stories" remain ripe for rediscovery — not only as fascinating objects in themselves but as documents of a popular culture still very much with us.

Cody himself would find himself on the sidelines when the film medium encroached upon his territory. His 1913 film epic, "The Indian Wars," was by all accounts a flop, and Cody eventually fell back upon a series of ill-advised business ventures and cut-rate performances. So too did the dime novels eventually give way to the neatly packaged narratives available via radio and cinema. But even with their all-but-inevitable obsolescence, the issues of "The Buffalo Bill Stories" remain ripe for rediscovery — not only as fascinating objects in themselves but as documents of a popular culture still very much with us.

Notes

- Larry McMurty. "Inventing the West," The New York Review of Books, Aug. 10, 2000.