Consistoire Central Israélite de France Collection

June 30, 2011

Description by Surella Evanor Seelig, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in history

Containing seven linear feet of French Consistory materials and two linear feet of international Judaica, the Consistoire Central Israélite de France collection at Brandeis provides a sweeping view of the French Jewish community from the mid-18th through the first third of the 20th-century. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of this collection is its provenance and relation to an ongoing debate in the academic world regarding the line between preservation and appropriation. Purchased in good faith by Brandeis some decades ago from a man named Zosa Szajkowski, this is but one of several similar collections held by institutions around the United States.

Containing seven linear feet of French Consistory materials and two linear feet of international Judaica, the Consistoire Central Israélite de France collection at Brandeis provides a sweeping view of the French Jewish community from the mid-18th through the first third of the 20th-century. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of this collection is its provenance and relation to an ongoing debate in the academic world regarding the line between preservation and appropriation. Purchased in good faith by Brandeis some decades ago from a man named Zosa Szajkowski, this is but one of several similar collections held by institutions around the United States.

Mr. Szajkowski, a prolific scholar of Jewish history, spent much of his life collecting French Judaica and selling or donating it to interested institutions (including Hebrew Union College, Yeshiva University, New York Public Library, Harvard University, Jewish Theological Seminary and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research). One of the many Jewish scholars who traveled to Europe in the years surrounding World War II to save European Judaica from destruction, Mr. Szajkowski was in good company in these endeavors, and much of his work during this era can be seen as the liberation or preservation of endangered and vital materials. But he continued removing materials long after the war was over and long after the danger was gone. Professor Lisa Leff of American University, who is currently in progress on a study of the intriguing Mr. Szajkowski, suggests that while the objective threat may have been gone during much of his collecting period, Zosa Szajkowski strongly believed postwar Europe to be an unsafe and unhealthy home for Jews and their history, and continued to think of himself as a liberator, as a rescuer of Jewish history. Professor Leff points out that although it is all but impossible to know, document-by-document, the origin of these particular materials with any certainty, Mr. Szajkowski was twice arrested for (and once convicted of) theft and those thefts raise questions about the collection's provenance. While there is good reason to think that much of what Mr. Szajkowski sold to Brandeis was not purely, honestly or openly come by, what can certainly be said about both his work and this collection is that they have allowed scholars extraordinary access to the workings of a fundamental institution of French Jewish history.

Mr. Szajkowski, a prolific scholar of Jewish history, spent much of his life collecting French Judaica and selling or donating it to interested institutions (including Hebrew Union College, Yeshiva University, New York Public Library, Harvard University, Jewish Theological Seminary and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research). One of the many Jewish scholars who traveled to Europe in the years surrounding World War II to save European Judaica from destruction, Mr. Szajkowski was in good company in these endeavors, and much of his work during this era can be seen as the liberation or preservation of endangered and vital materials. But he continued removing materials long after the war was over and long after the danger was gone. Professor Lisa Leff of American University, who is currently in progress on a study of the intriguing Mr. Szajkowski, suggests that while the objective threat may have been gone during much of his collecting period, Zosa Szajkowski strongly believed postwar Europe to be an unsafe and unhealthy home for Jews and their history, and continued to think of himself as a liberator, as a rescuer of Jewish history. Professor Leff points out that although it is all but impossible to know, document-by-document, the origin of these particular materials with any certainty, Mr. Szajkowski was twice arrested for (and once convicted of) theft and those thefts raise questions about the collection's provenance. While there is good reason to think that much of what Mr. Szajkowski sold to Brandeis was not purely, honestly or openly come by, what can certainly be said about both his work and this collection is that they have allowed scholars extraordinary access to the workings of a fundamental institution of French Jewish history.

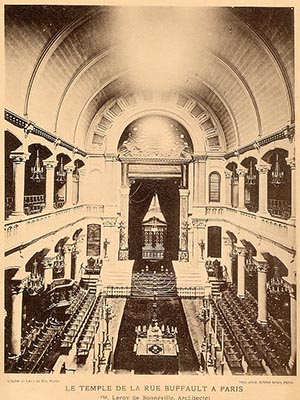

The Consistoire Central Israélite de France was an administrative body (modeled on the Catholic Church and the Protestant Consistories) through which the Jewish community organized, self-governed and interacted with the French state. It was created by Napoleon in the early years of the 19th century and exists (in altered format) to this day. Despite having a complicated and none-too-altruistic relationship with the Jews of France, Napoleon, in creating the Consistoire, brought about a magnificent stronghold of Jewish life, religion and culture, one that would sustain its community through two centuries of religious, political and military ruptions.

The Consistoire Central Israélite de France was an administrative body (modeled on the Catholic Church and the Protestant Consistories) through which the Jewish community organized, self-governed and interacted with the French state. It was created by Napoleon in the early years of the 19th century and exists (in altered format) to this day. Despite having a complicated and none-too-altruistic relationship with the Jews of France, Napoleon, in creating the Consistoire, brought about a magnificent stronghold of Jewish life, religion and culture, one that would sustain its community through two centuries of religious, political and military ruptions.

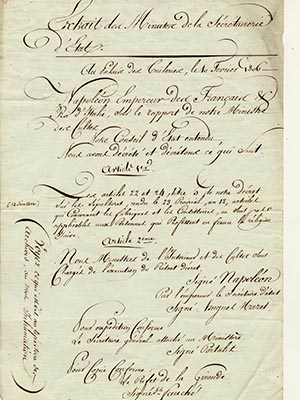

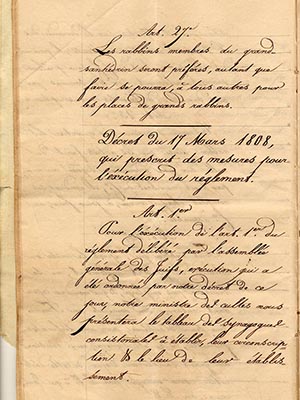

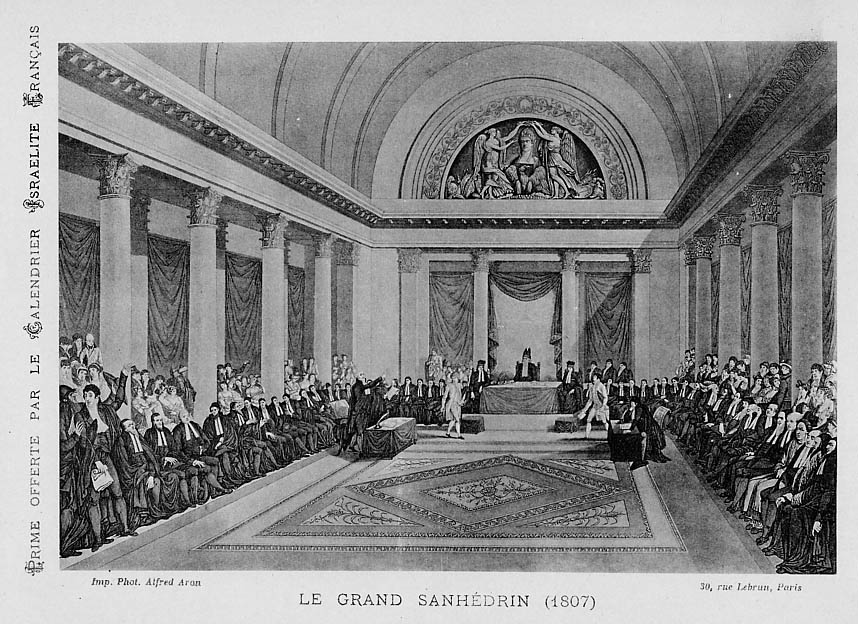

In 1806, Napoleon gathered an Assembly of Jewish notables led by Rabbi David Sinzheim of Strasbourg, and put to them 12 questions through which he established the relationship between the laws of the Jewish community and the laws of France.  The answers to these questions laid the groundwork for the future consistorial laws. In 1807 he established a Grand Sanhedrin (supreme legal body of Jewish law), an institution that had not sat for roughly 1500 years, and in 1808, in conjunction with a committee of Sanhedrin members, he organized the Consistoire. Every department where at least 2,000 Jewish people lived could create a consistory and appoint a Chief Rabbi; those with fewer than 2,000 could combine with others to form a regional consistory. All were to be overseen by a central consistory and the Chief Rabbi of France.

The answers to these questions laid the groundwork for the future consistorial laws. In 1807 he established a Grand Sanhedrin (supreme legal body of Jewish law), an institution that had not sat for roughly 1500 years, and in 1808, in conjunction with a committee of Sanhedrin members, he organized the Consistoire. Every department where at least 2,000 Jewish people lived could create a consistory and appoint a Chief Rabbi; those with fewer than 2,000 could combine with others to form a regional consistory. All were to be overseen by a central consistory and the Chief Rabbi of France.

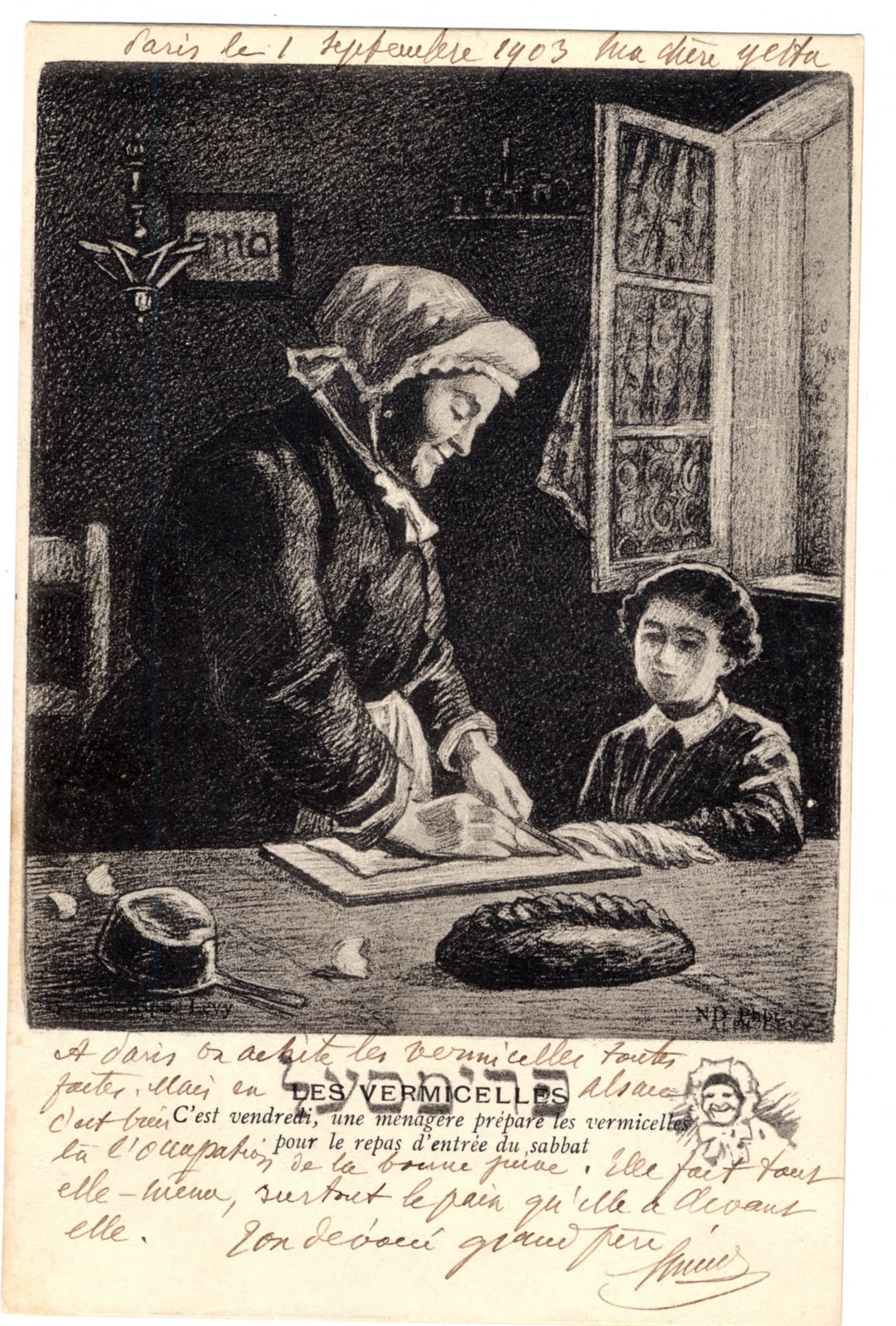

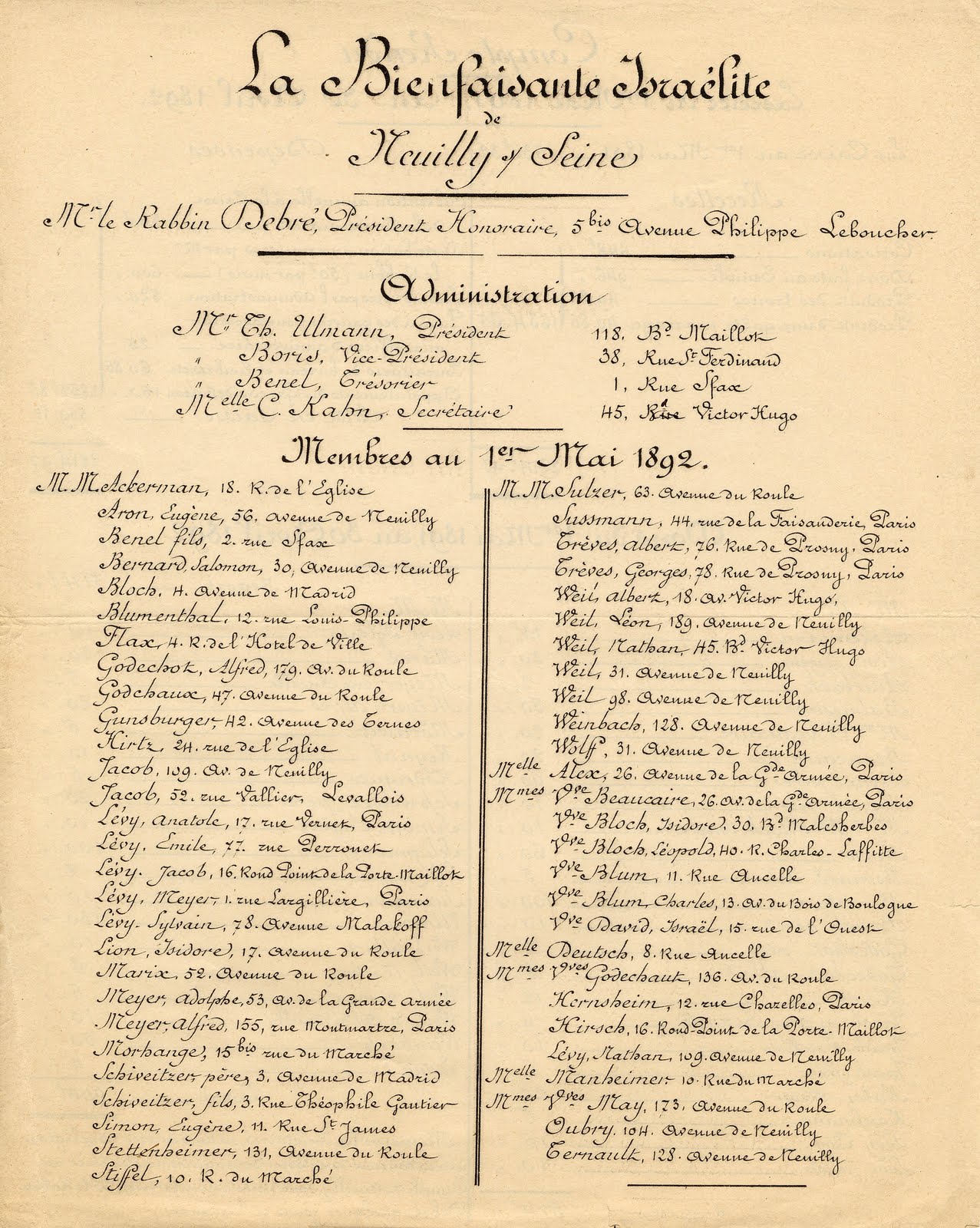

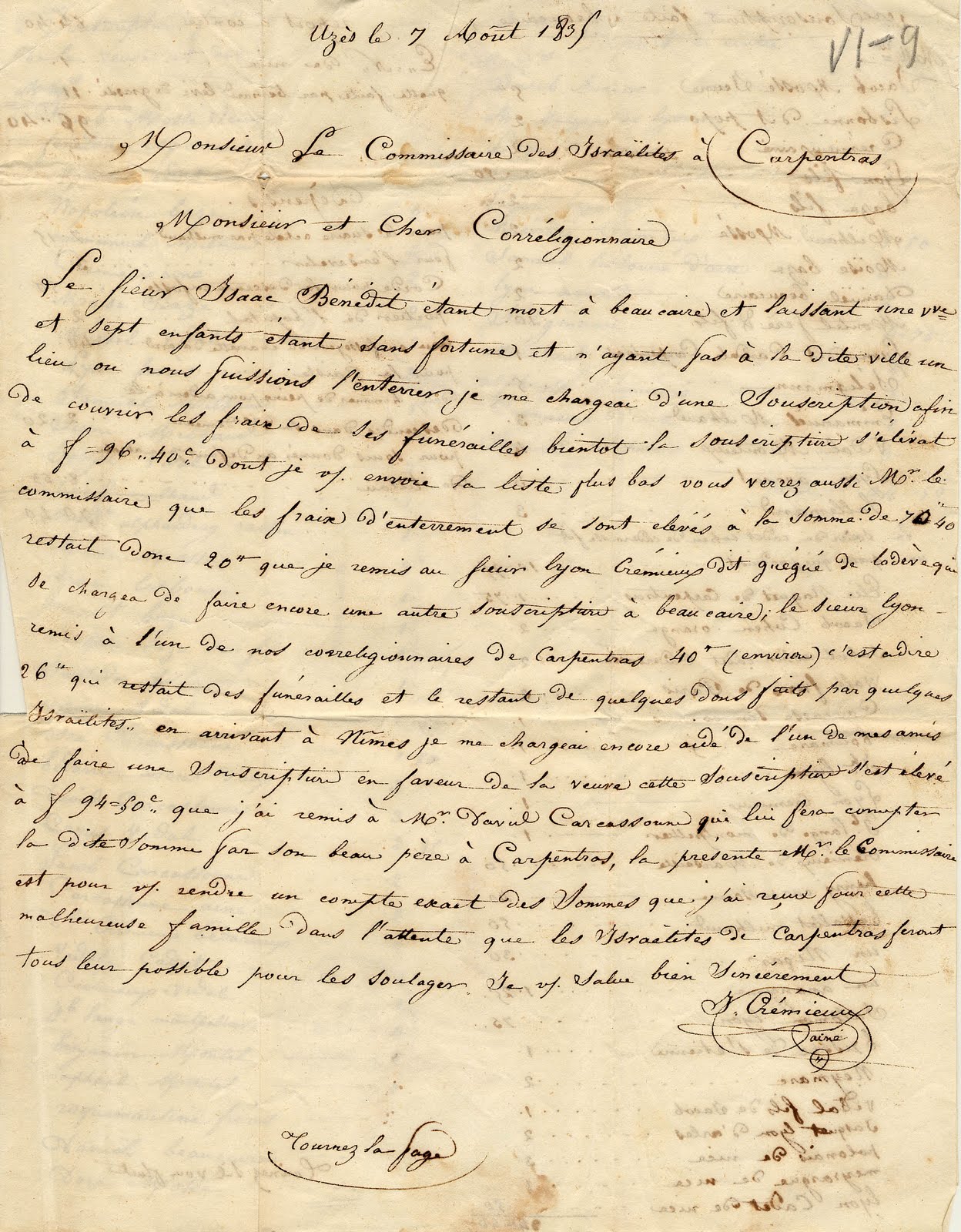

This collection documents the workings of the many provincial consistories as well as the Central Consistory in Paris, and gives a detailed picture of the ways in which these bodies oversaw both the religious and the secular aspects of French Jewish life. The business of the Consitories can be seen to be trifold. The religious aspects included the election of the Chief Rabbis, the establishment and running of the Synagogue and Beth Din (rabbinical court), the regulation of kosher butchers and funerary rites, etc. The second function can be generally classified under the rubric of social welfare: the creation and maintenance of orphanages, hospitals, schools, cemeteries and charities. The third category was that of secular and political administration, including the maintenance of a strong relationship with the French government and between the consistories, and data collection (budgets, population tables, prisoners rolls, birth registries, etc). Boasting documents dating from long before the French Revolution to the interwar years of the 20th-century, this collection tells the complicated story of the relationship of the Jewish community both to itself and to the French State.

This collection documents the workings of the many provincial consistories as well as the Central Consistory in Paris, and gives a detailed picture of the ways in which these bodies oversaw both the religious and the secular aspects of French Jewish life. The business of the Consitories can be seen to be trifold. The religious aspects included the election of the Chief Rabbis, the establishment and running of the Synagogue and Beth Din (rabbinical court), the regulation of kosher butchers and funerary rites, etc. The second function can be generally classified under the rubric of social welfare: the creation and maintenance of orphanages, hospitals, schools, cemeteries and charities. The third category was that of secular and political administration, including the maintenance of a strong relationship with the French government and between the consistories, and data collection (budgets, population tables, prisoners rolls, birth registries, etc). Boasting documents dating from long before the French Revolution to the interwar years of the 20th-century, this collection tells the complicated story of the relationship of the Jewish community both to itself and to the French State.

The material within the two linear feet of non-consistorial Judaica is as wide ranging geographically as the consistorial materials are temporally. While many of the pieces revolve around French Jewry, there is a significant section devoted to its relationships with Jewish societies in countries around the world, including Puerto Rico, the United States, Russia, Turkey and Israel.

The material within the two linear feet of non-consistorial Judaica is as wide ranging geographically as the consistorial materials are temporally. While many of the pieces revolve around French Jewry, there is a significant section devoted to its relationships with Jewish societies in countries around the world, including Puerto Rico, the United States, Russia, Turkey and Israel.

There are several pieces of correspondence from and to various notables in the international Jewish community, including Baron Edmond James de Rothschild and Lucien Wolf. The relationship between Jews and the French State during times of war is documented in materials from the Jewish community in Bordeaux’s 28 districts during the French Revolution as well as the activities of French Jewry during World War I. This material opens a window onto the interactions of the worldwide Jewish community, both within itself and with the secular community.

While this collection has considerable scholarly merit in its own right, scholars may find its connections to other Brandeis Special Collections holdings to be particularly interesting, specifically, the Lipschutz Collection of Dreyfusiana and French Judaica and the Benjamin A. and Julia M. Trustman Collection of Honoré Daumier Lithographs. Considering the wide time frame of both the Consistoire and the Lipschutz collection, it is hardly surprising to find crossover. The interactions between the two collections are related both to French Jewish life in general and to the Dreyfus Affair in particular: both collections make noteworthy references to Zadoc Kahn, Grand-Rabbin of France, who officiated at Alfred and Lucie Dreyfus’s wedding and testified on Dreyfus’ behalf during his trial and its aftermath.

While this collection has considerable scholarly merit in its own right, scholars may find its connections to other Brandeis Special Collections holdings to be particularly interesting, specifically, the Lipschutz Collection of Dreyfusiana and French Judaica and the Benjamin A. and Julia M. Trustman Collection of Honoré Daumier Lithographs. Considering the wide time frame of both the Consistoire and the Lipschutz collection, it is hardly surprising to find crossover. The interactions between the two collections are related both to French Jewish life in general and to the Dreyfus Affair in particular: both collections make noteworthy references to Zadoc Kahn, Grand-Rabbin of France, who officiated at Alfred and Lucie Dreyfus’s wedding and testified on Dreyfus’ behalf during his trial and its aftermath.

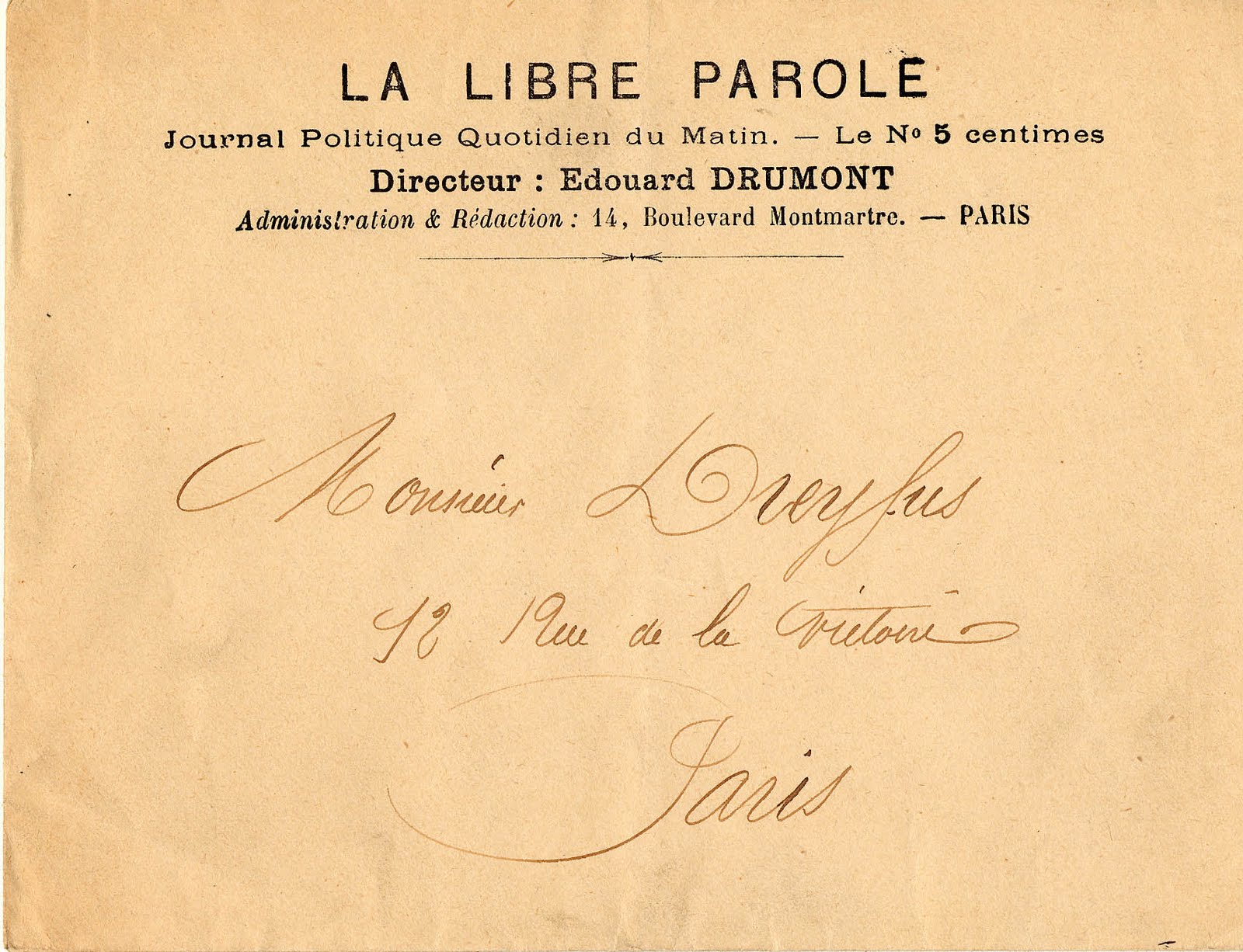

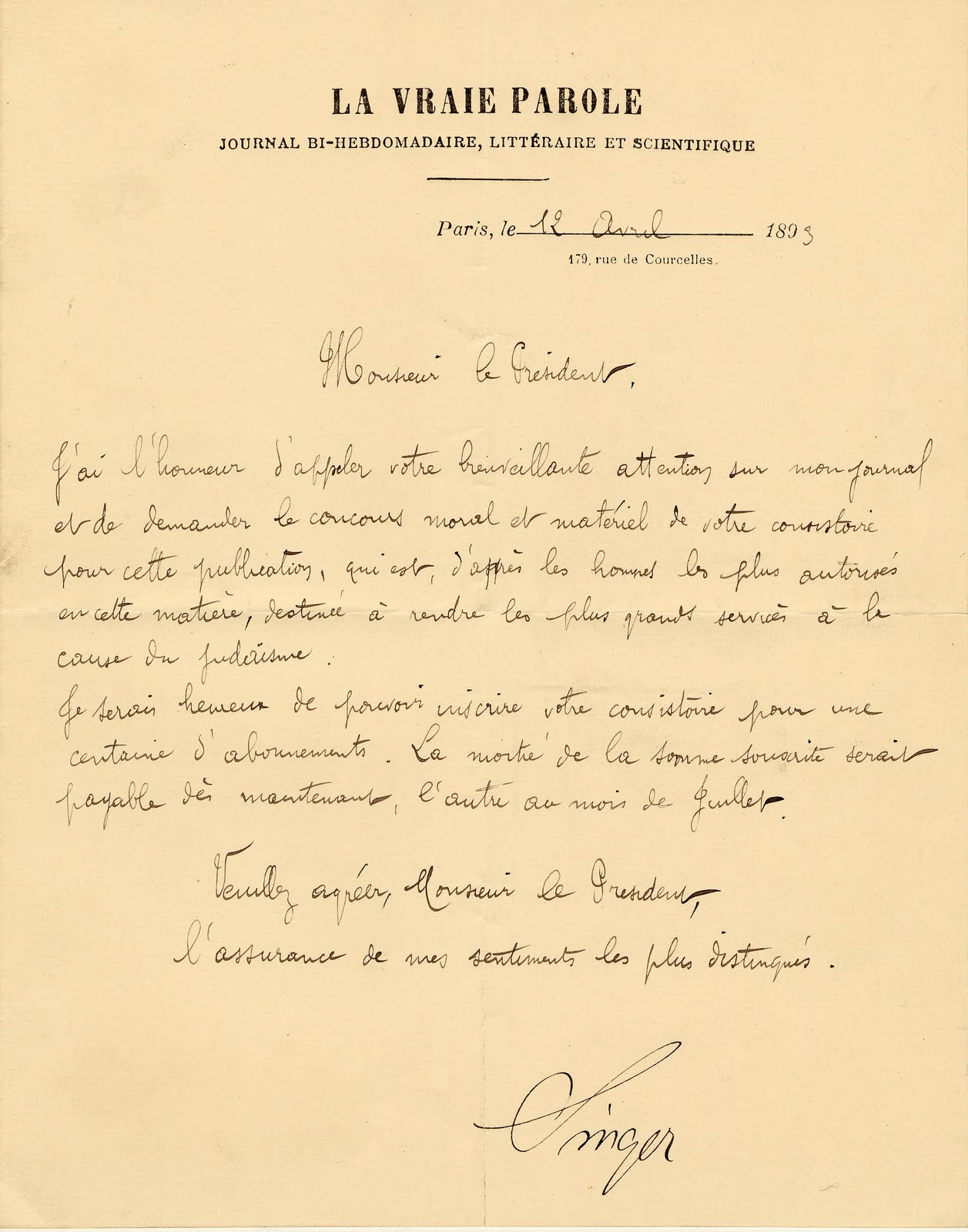

The Consistoire collection also contains correspondence and other materials regarding La Vraie Parole, a journal created and edited by Isadore Singer in order to counter the effects of Édouard Drumont’s virulently anti-Semitic La Libre Parole (of which the Lipschutz collection has a number of editions). While Drumont’s paper was a driving force behind the anti-Dreyfusard movement, Singer made La Vraie Parole a vocal and staunch supporter of Captain Dreyfus. Relating more specifically to Consistorial matters, included as well in the Lipschutz collection is a handwritten “Allocution” addressed to the president of the Central Consistory. The third box of the Consistoire collection begins with documentation of the Metz consistory, and the Lipschutz collection contains several documents pertaining to that community, not the least interesting of which is the typed report on the Jews of Metz written by its Chief Rabbi, Nathan Netter (The Consistoire collection contains two letters specifically relating to the work of Rabbi Netter). The Lipschutz collection boasts correspondence between Chief Rabbi of France Dreyfuss and Manuel, the Secretary General of the Central Consistory.

The Consistoire collection also contains correspondence and other materials regarding La Vraie Parole, a journal created and edited by Isadore Singer in order to counter the effects of Édouard Drumont’s virulently anti-Semitic La Libre Parole (of which the Lipschutz collection has a number of editions). While Drumont’s paper was a driving force behind the anti-Dreyfusard movement, Singer made La Vraie Parole a vocal and staunch supporter of Captain Dreyfus. Relating more specifically to Consistorial matters, included as well in the Lipschutz collection is a handwritten “Allocution” addressed to the president of the Central Consistory. The third box of the Consistoire collection begins with documentation of the Metz consistory, and the Lipschutz collection contains several documents pertaining to that community, not the least interesting of which is the typed report on the Jews of Metz written by its Chief Rabbi, Nathan Netter (The Consistoire collection contains two letters specifically relating to the work of Rabbi Netter). The Lipschutz collection boasts correspondence between Chief Rabbi of France Dreyfuss and Manuel, the Secretary General of the Central Consistory.

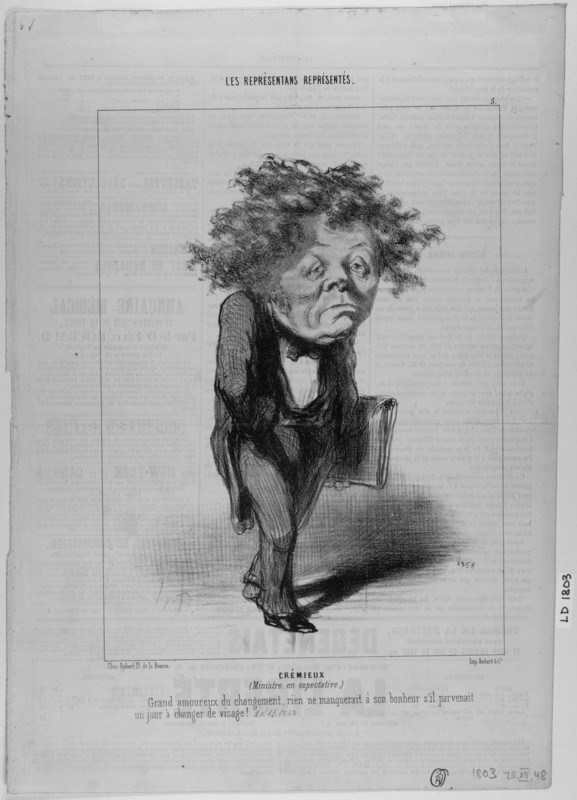

Included as well in the Consistoire collection are some letters of Adolphe Crémieux, a French Jewish statesman and lawyer who served as vice-president of the Central Consistory for close to 50 years. Crémieux is caricatured in four of Honoré Daumier’s lithographs. All four of these are held by the Special Collections Department at Brandeis in what is one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of Daumier’s lithographs in the world.

Included as well in the Consistoire collection are some letters of Adolphe Crémieux, a French Jewish statesman and lawyer who served as vice-president of the Central Consistory for close to 50 years. Crémieux is caricatured in four of Honoré Daumier’s lithographs. All four of these are held by the Special Collections Department at Brandeis in what is one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of Daumier’s lithographs in the world.

The Consistoire Central Israélite de France collection at Brandeis opens the door to many levels of scholarly investigation. It fleshes out the Special Collections’ growing collection of French history and Judaica, it is a boon to historians and religious scholars alike, and it will likely instigate discussions about the ethics behind the removal and preservation of historically significant documents and artifacts.

Heartfelt thanks to Professor Lisa Leff of American University for sharing her remarkable research and insight into Zosa Szajkowski, and to Professor Jonathan Sarna of Brandeis University for pointing me in her direction.