The Crimean War in the French and British Satirical Press

February 1, 2017

Political intrigue has long served as artistic fodder, and political cartoons provide a particularly fascinating way to trace the winding paths of historical events, and the way in which this amusing and often subversive commentary offered readers alternative viewpoints on the events of the day. This post explores the way in which people and events connected with the Crimean War were represented in the French and British satirical press. It focuses specifically on cartoons by Honoré Daumier, John Tenniel and John Leech that appeared in Le Charivari (France) and Punch, or the London Charivari (England), two major 19th-century satirical publications.

Special Collections is proudly home to several collections featuring the art of political satire, including one of the major Daumier collections in the United States. The Benjamin A. and Julia M. Trustman Collection of Honoré Daumier Lithographs (collection finding aid) comprises nearly the entire oeuvre of Daumier in the lithographic medium, making it a unique resource for the study of Daumier’s art and 19th-century French history. The entire collection of lithographs has been digitized and placed in the Brandeis Distinctive Collections (BDC). This digitization was made possible by a 2001 Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant. See the Daumier Spotlight for more information about the Trustman collection as a whole and the Spotlight on Punch’s Pocket Book for more about that Punch-offshoot publication. Partial or whole runs of Punch, The Illustrated London News, and Le Charivari can be found in the Library stacks and in Special Collections.

Introduction

The Russo-Turkish War and the subsequent Crimean War flared between 1853 and 1856, and together they constituted the largest international conflict involving European powers between the Napoleonic Wars and World War I. Starting in 1851, political tensions ran high between France and Russia over which country should serve as guardian of the Christian Holy Places in Palestine, which at the time fell within the borders of the Ottoman Empire. After the Turks granted guardianship of the Holy Places to France, Russia reacted by occupying the Danubian Principalities on July 2, 1853 and invading Ottoman territory on March 20, 1854. One week later, Britain and France joined Turkey in declaring war on Russia. The Turks surprisingly beat the Russians back, pushing them out of Ottoman territory. Russia, however, refused to accept the terms of peace, prompting an invasion of the Crimea by Great Britain and France with the goal of capturing the naval port at Sebastopol and forcing Russia into submission.

The Crimean War has been termed the first media war. The development of the telegraph allowed news of the war to be sent home within days rather than weeks. Photography for the first time captured the brutality of war, and these images stirred up considerable outcries among the English and French public. Due to the obscure politics driving the war and the almost immediate reportage of events on the battle fields, popular enthusiasm in support of the war never materialized in England or France.

During the time of the Crimean War, Le Charivari and Punch were the leading satirical publications in France and England, respectively. The French artist Honoré Daumier published many of his famous lithographs in Le Charivari, while John Leech and John Tenniel (the original illustrator of the Alice in Wonderland books) produced almost all of the illustrations for Punch. These political cartoonists reflected the public’s general ambivalence towards the war by lampooning the botched diplomacy and inept military leadership that led to needless suffering among the soldiers. Most of their satirical invective, however, was aimed at Russia and its role in fomenting war.

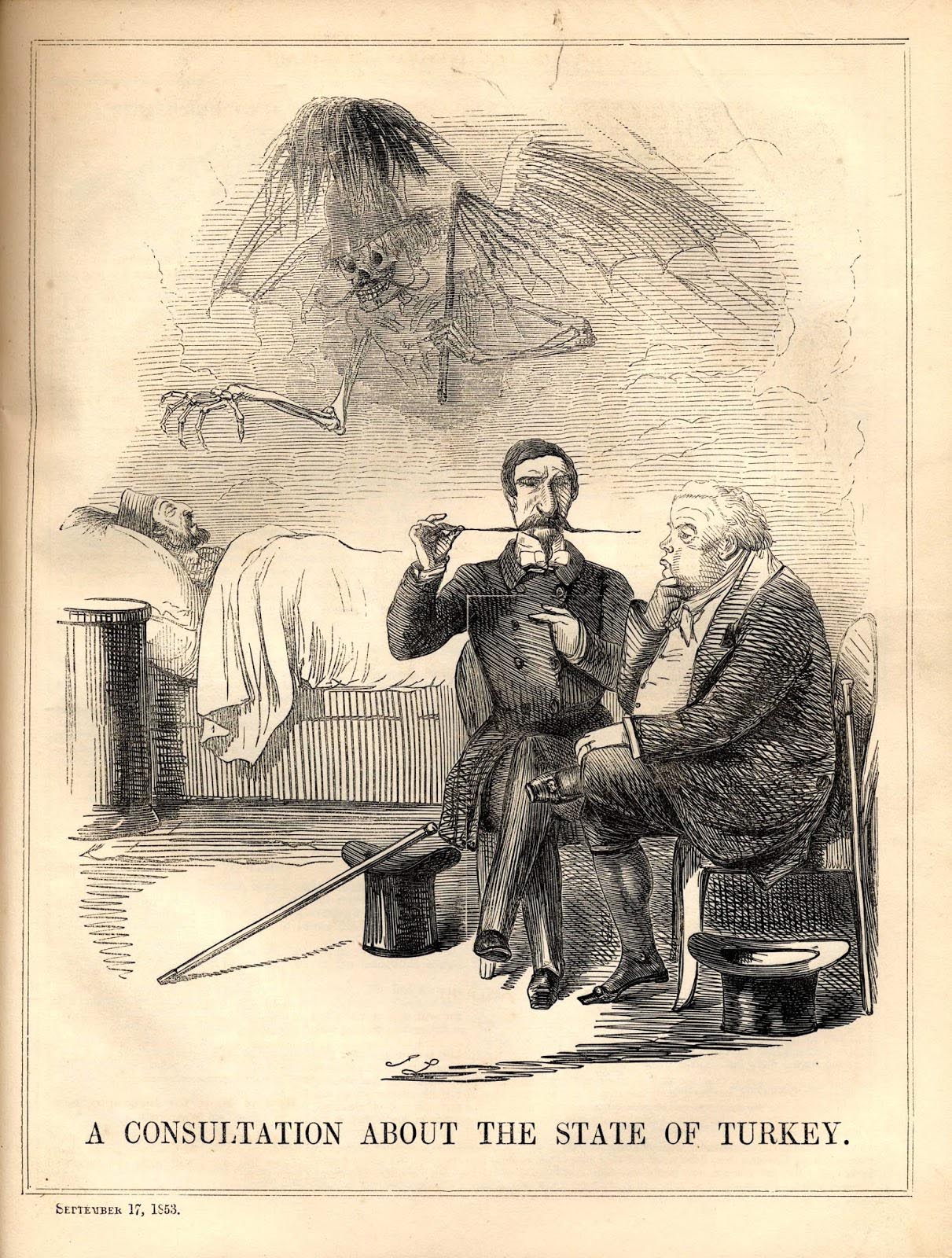

The Crimean War: The Turkish Question

From The History of the War Against Russia by Edward Henry Nolan. London: Virtue, [1855-57?].

This map shows the area of conflict during the Crimean War. In crossing the Danube River on the western edge of the Black Sea and into Ottoman territory, the Russians had designs on moving south and taking over Constantinople to open up easy shipping lanes to the Mediterranean. When this plan was thwarted by the Turks, the theater of war shifted to the Crimea, the peninsula that sits at the northern part of the Black Sea.

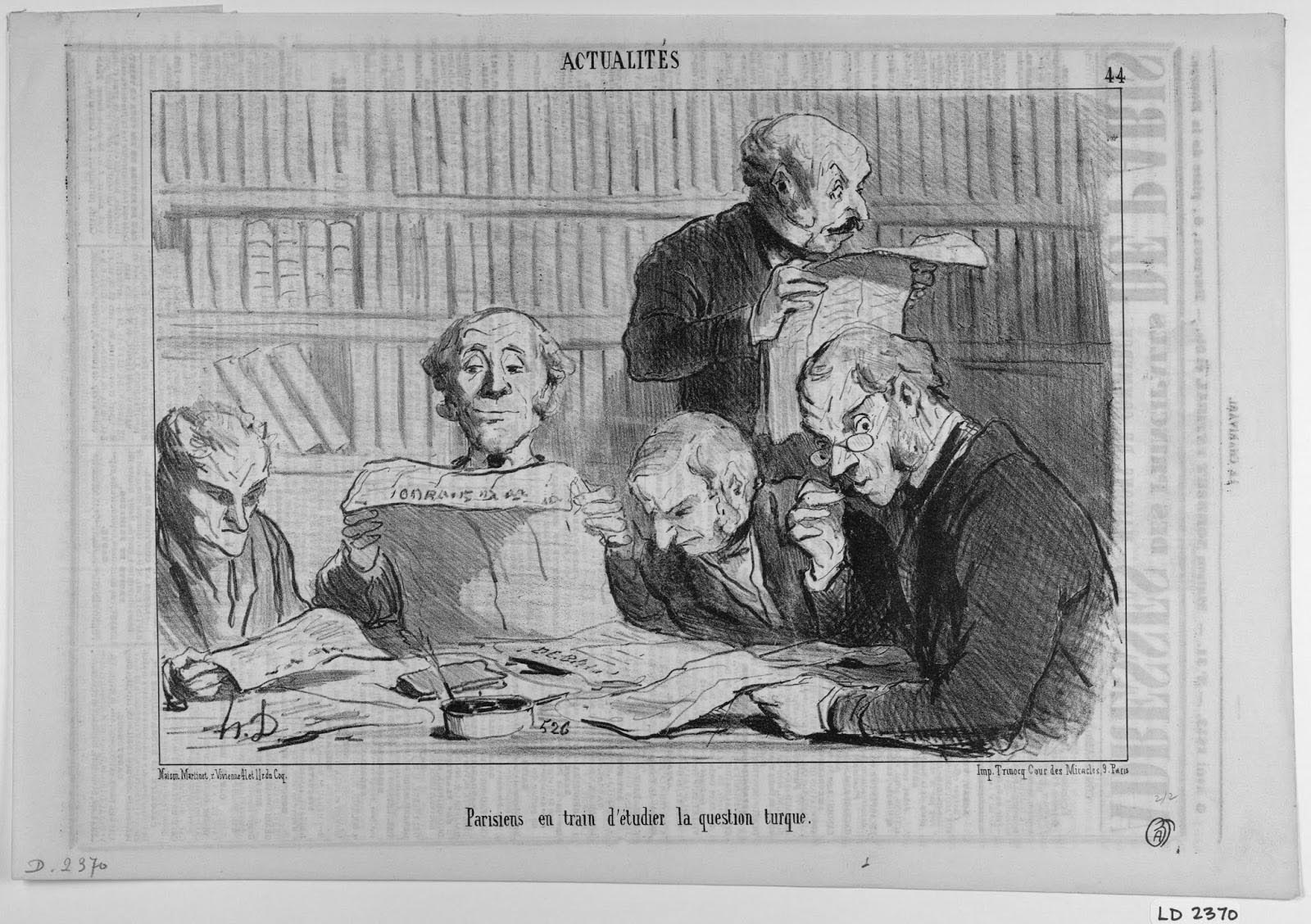

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 44. Le Charivari. August 4, 1853. LD 2370.

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 44. Le Charivari. August 4, 1853. LD 2370.

The Russian army crossed the Pruth River on July 3, 1853 and occupied Bucharest by July 15, bringing the Danubian Principalities under Russian control. The French press relentlessly reported on these events and the threat of war.

Czar Nicholas I

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 94. Le Charivari. August 8, 1850. LD 1999.

Trampling on a map of France in his war room, Czar Nicholas I of Russia brandishes his sword and loses his hat while a Cossack looks on, his spear pointed at France. The Czar conducted an often openly hostile relationship with France.

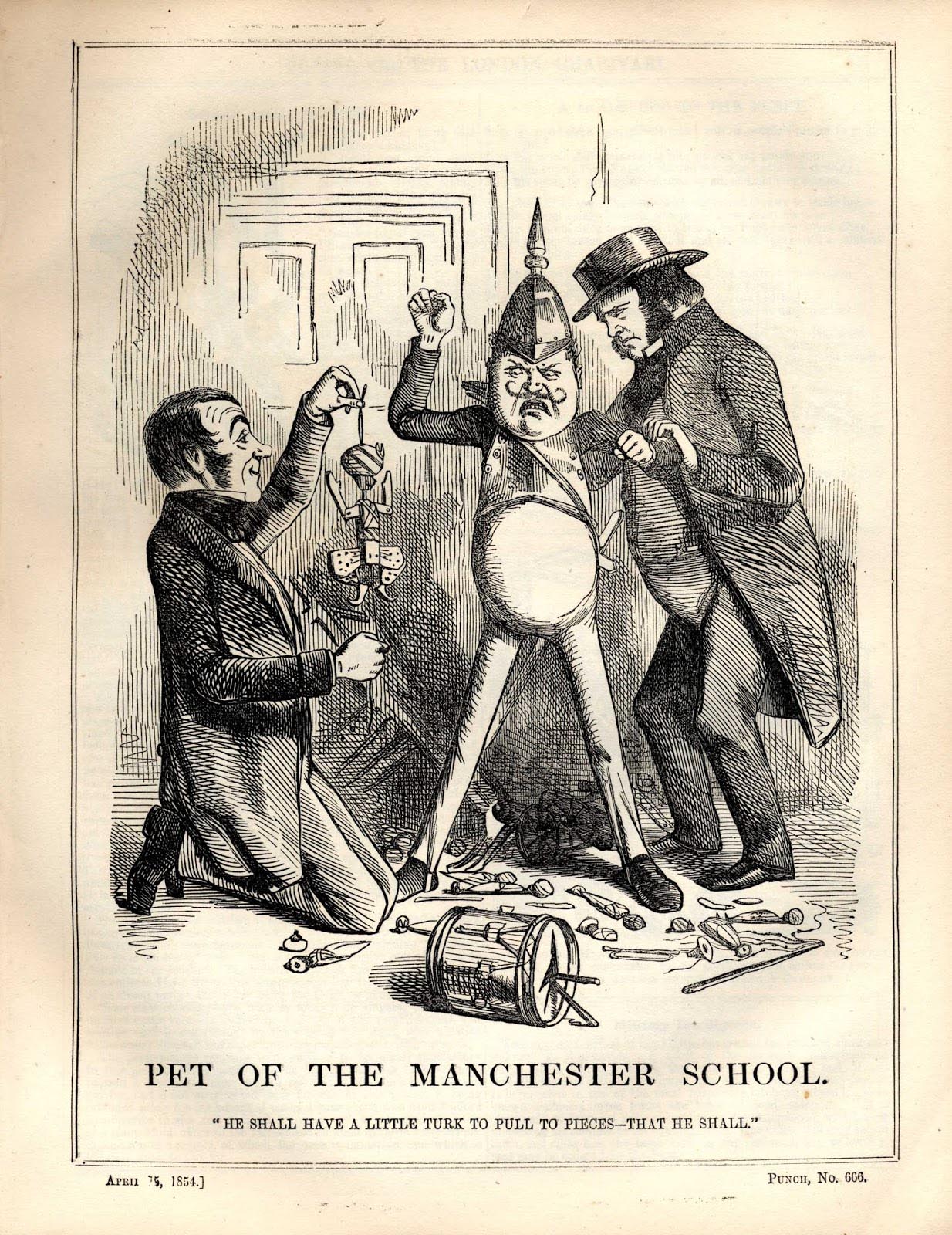

John Tenniel. Cartoon. Punch. April 15, 1854.

Richard Cobden, a leading supporter of the Peace Society, and John Bright, a Quaker and member of Parliament, both openly opposed war with Russia. These two politicians from Manchester are shown facilitating a tantrum by Czar Nicholas I and his attempts to destroy the Turkish Empire.

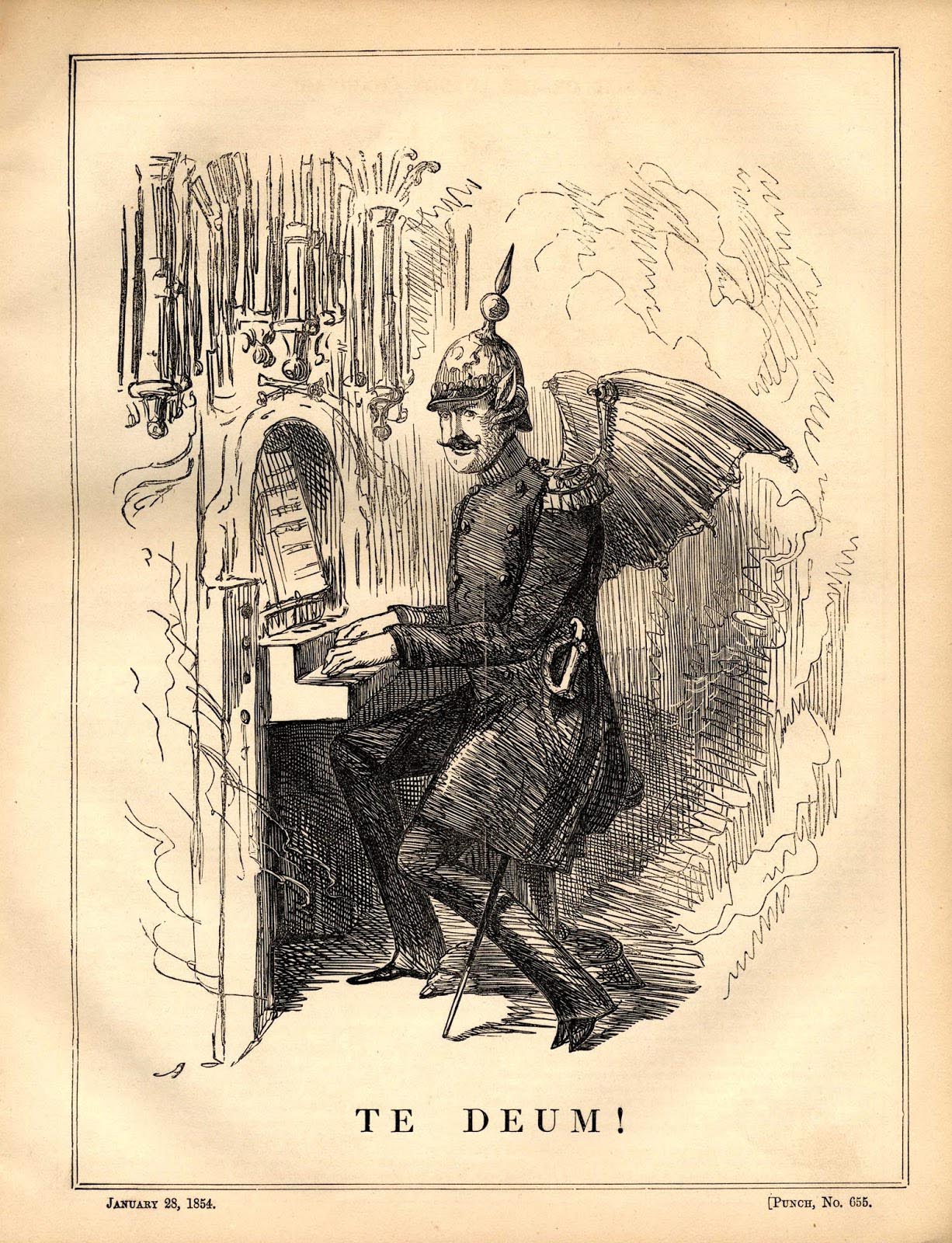

[A traditional Christian hymn of joy and thanksgiving.]

John Leech. Cartoon. Punch. January 28, 1854.

Russia, purportedly representing the interests of the Greek Orthodox Church, sought to serve as the protectorate of the Christian Holy Places lying within Turkish territory. The general opinion in Europe was that Czar Nicholas I used Turkey’s refusal to grant Russia this privilege as a pretext to carry out his true desire, namely to destroy the Ottoman Empire. This view informs the depiction of Czar Nicholas I as a devil figure within a religious setting. Note the cloven hoof in place of his left foot.

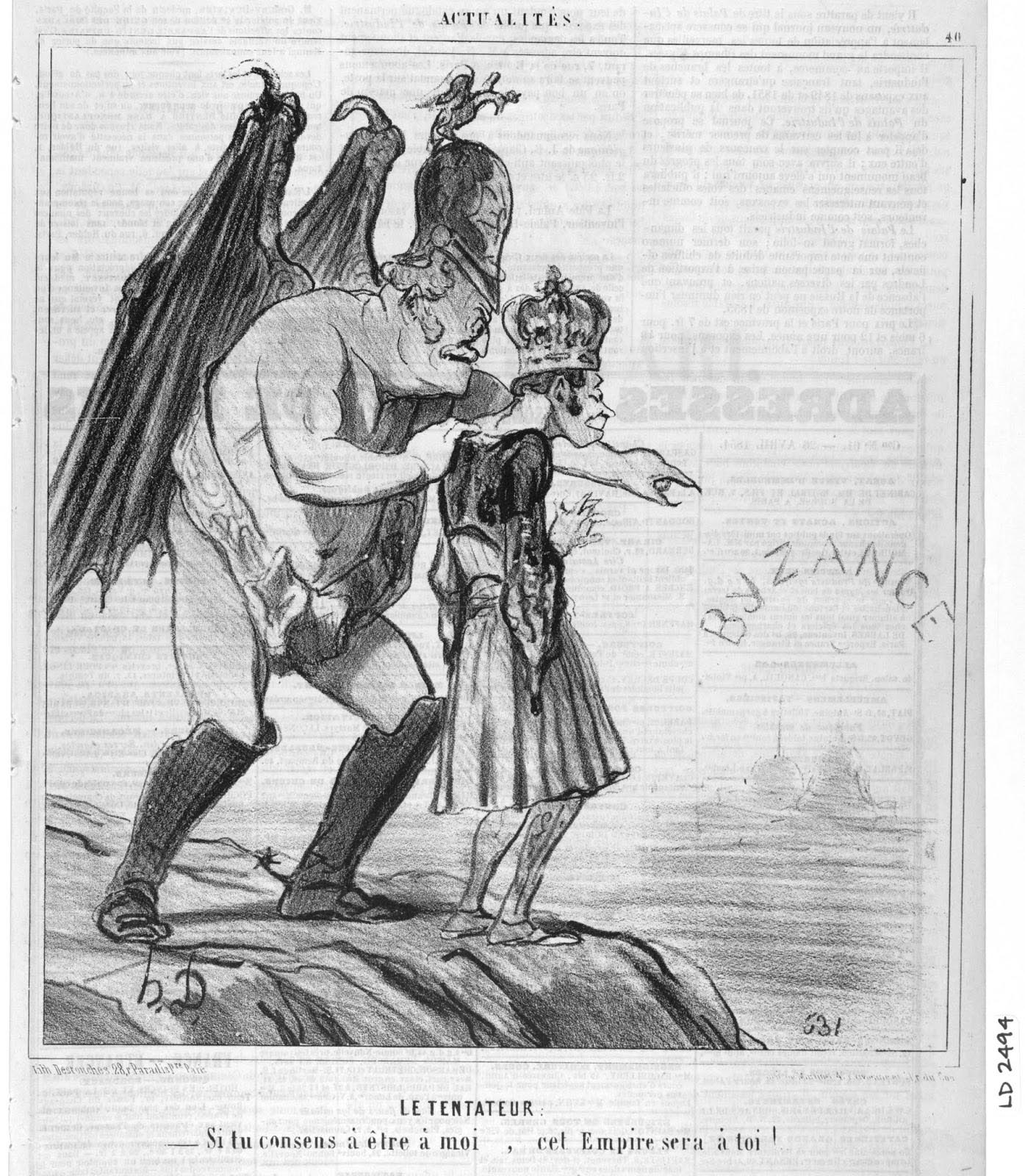

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 40. Le Charivari. April 26, 1854. LD 2494.

Traditional allies of Russia stayed out of the war, leaving Russia isolated. Daumier here draws upon the iconography of the Temptation of Christ: Nicholas I as the Devil tempts the Greek king, Otto I, to enter the war with the prize of Constantinople and a revival of the Byzantine Empire in a conquered Turkey.

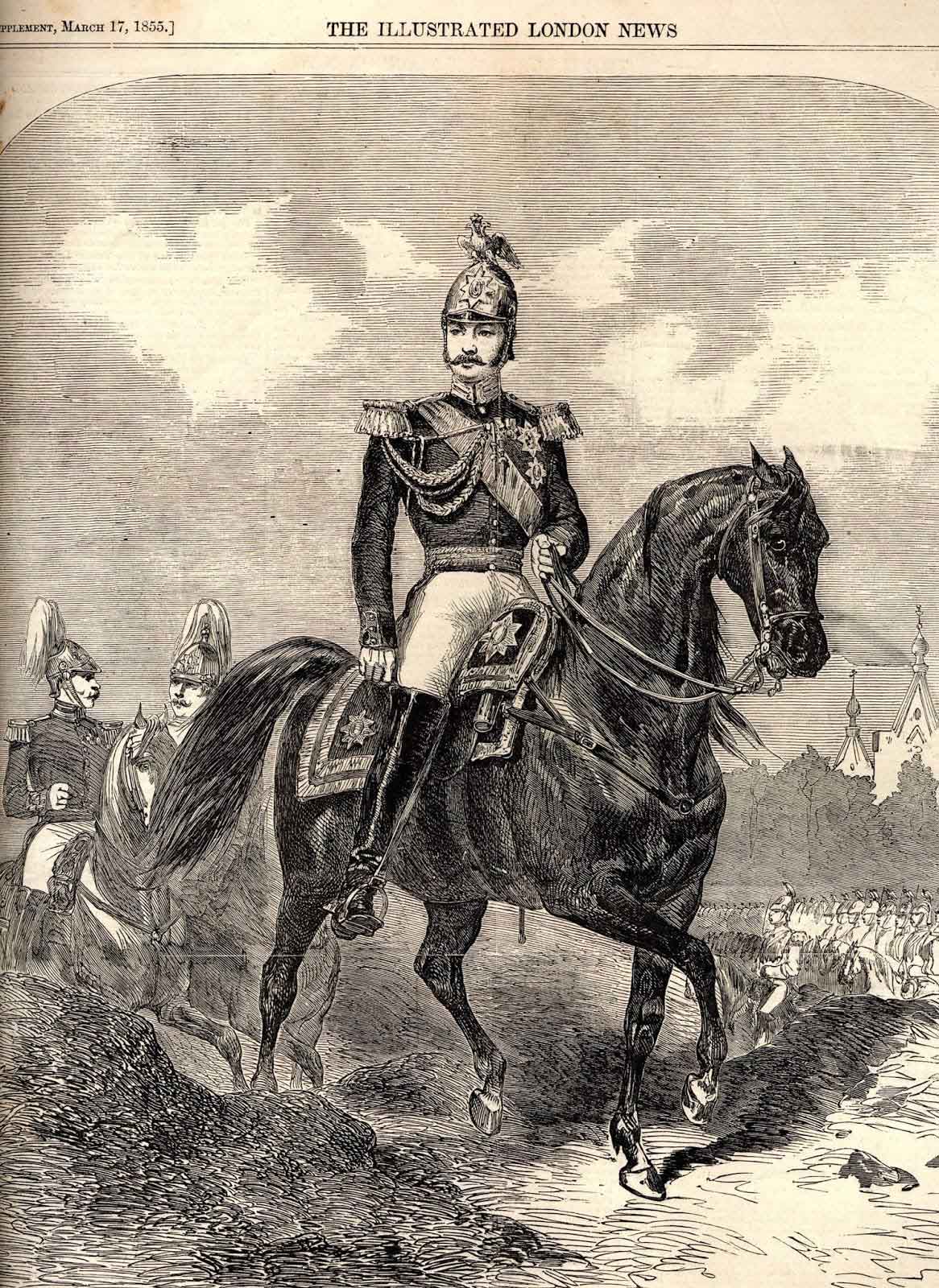

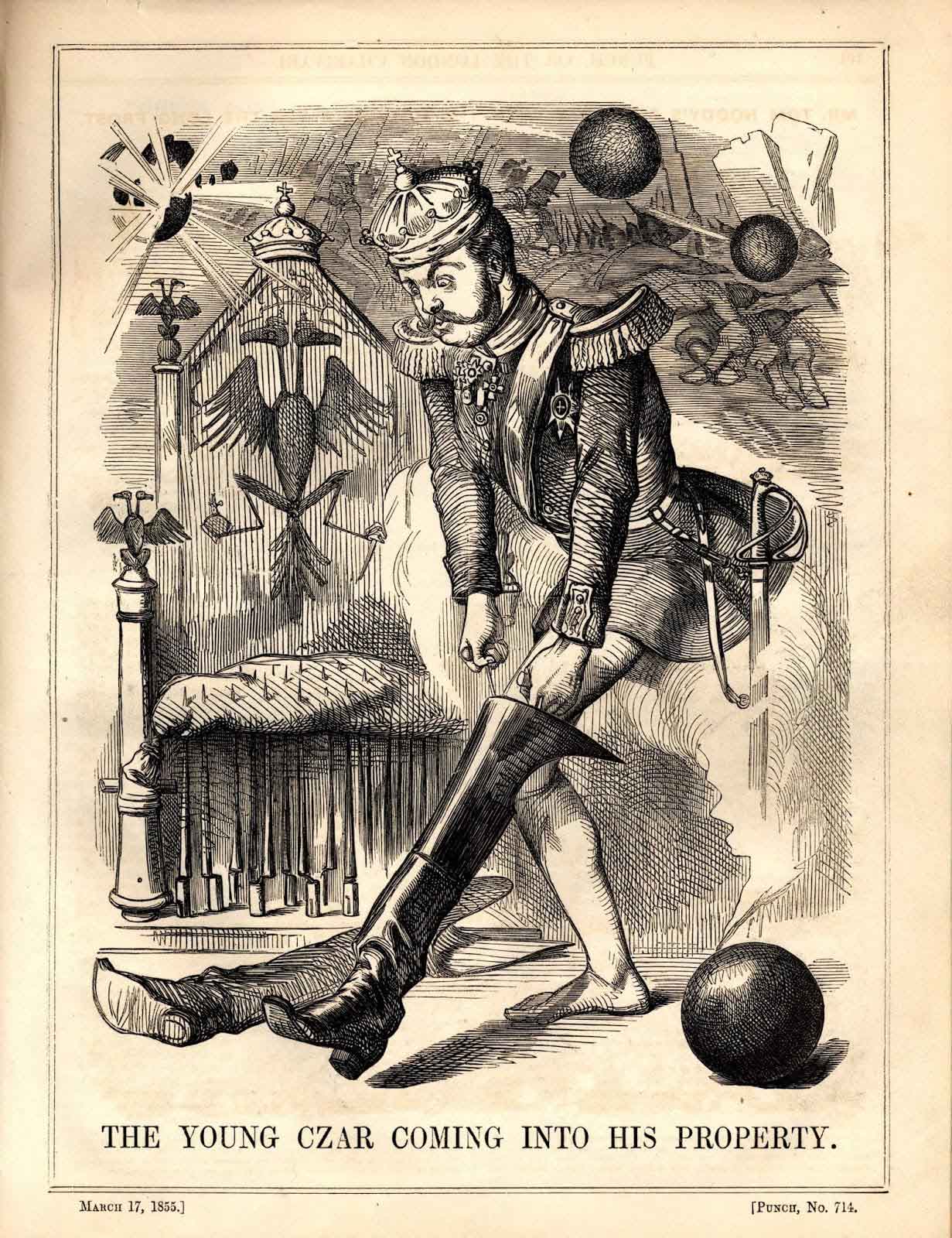

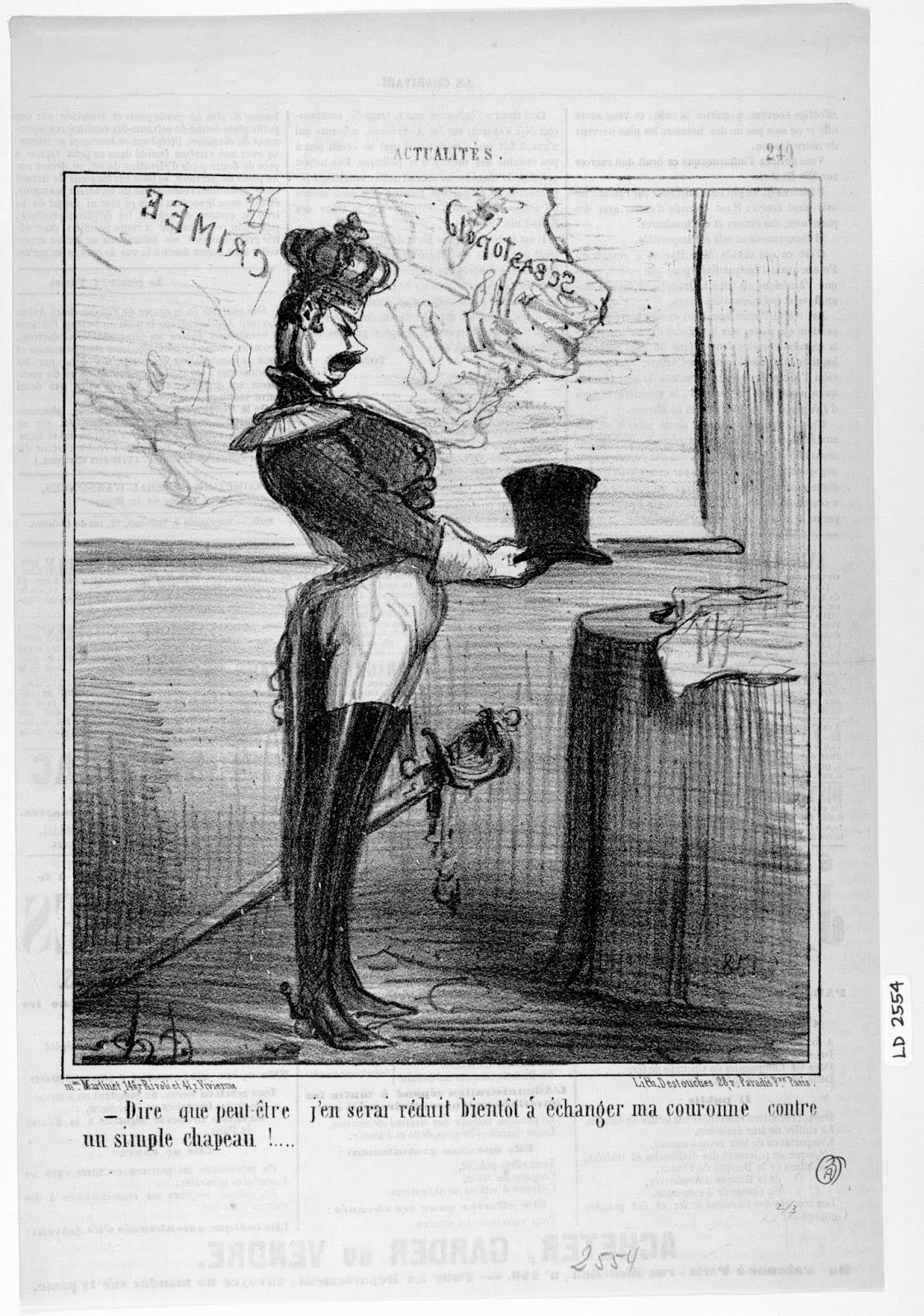

Czar Alexander II

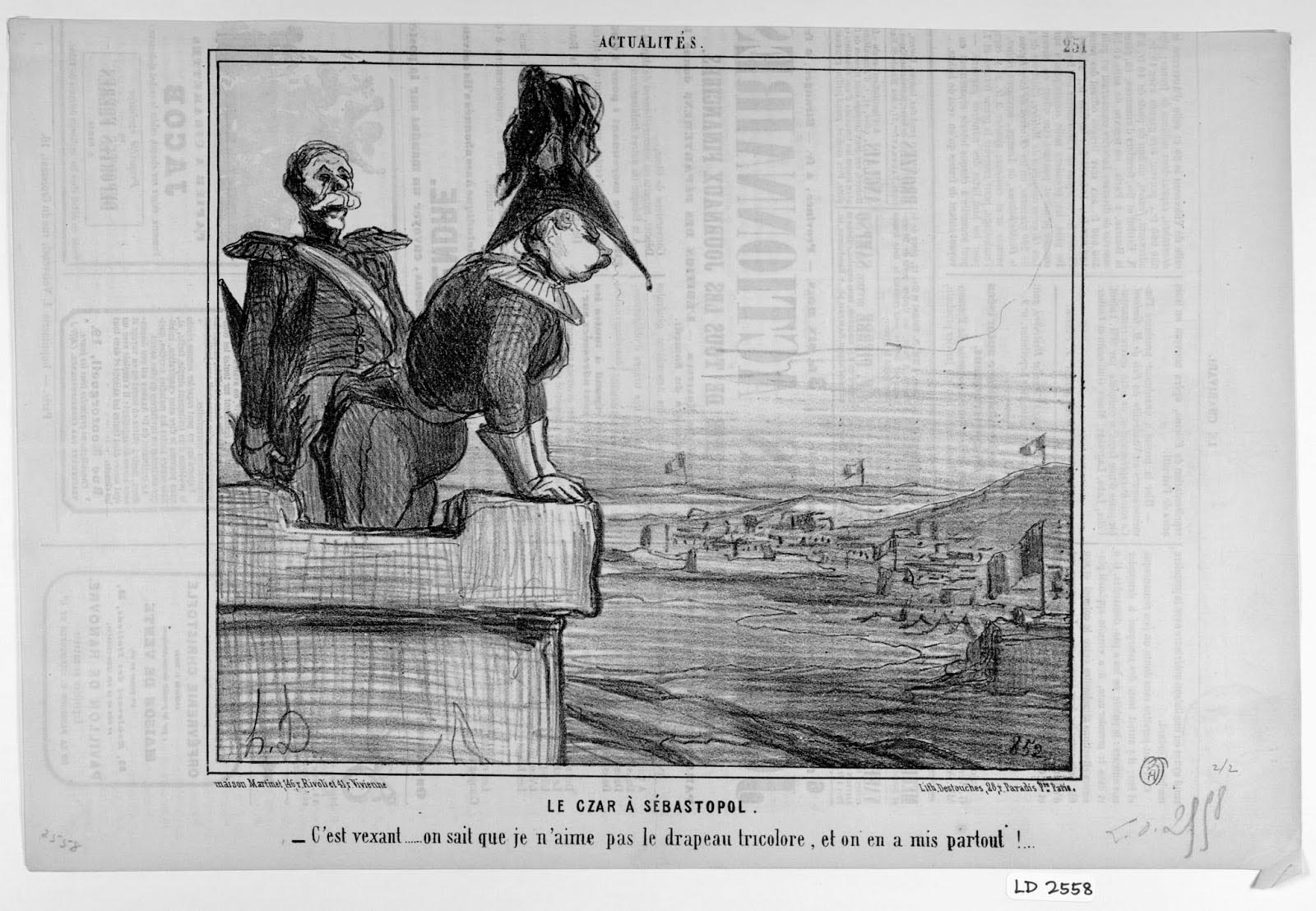

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 251. Le Charivari. December 29, 1855. LD 2558.

The Russians lost Sebastopol to the Allied Army on September 11, 1855. A frustrated Czar Alexander II looks over the Russian naval port, only to see it occupied by the French.

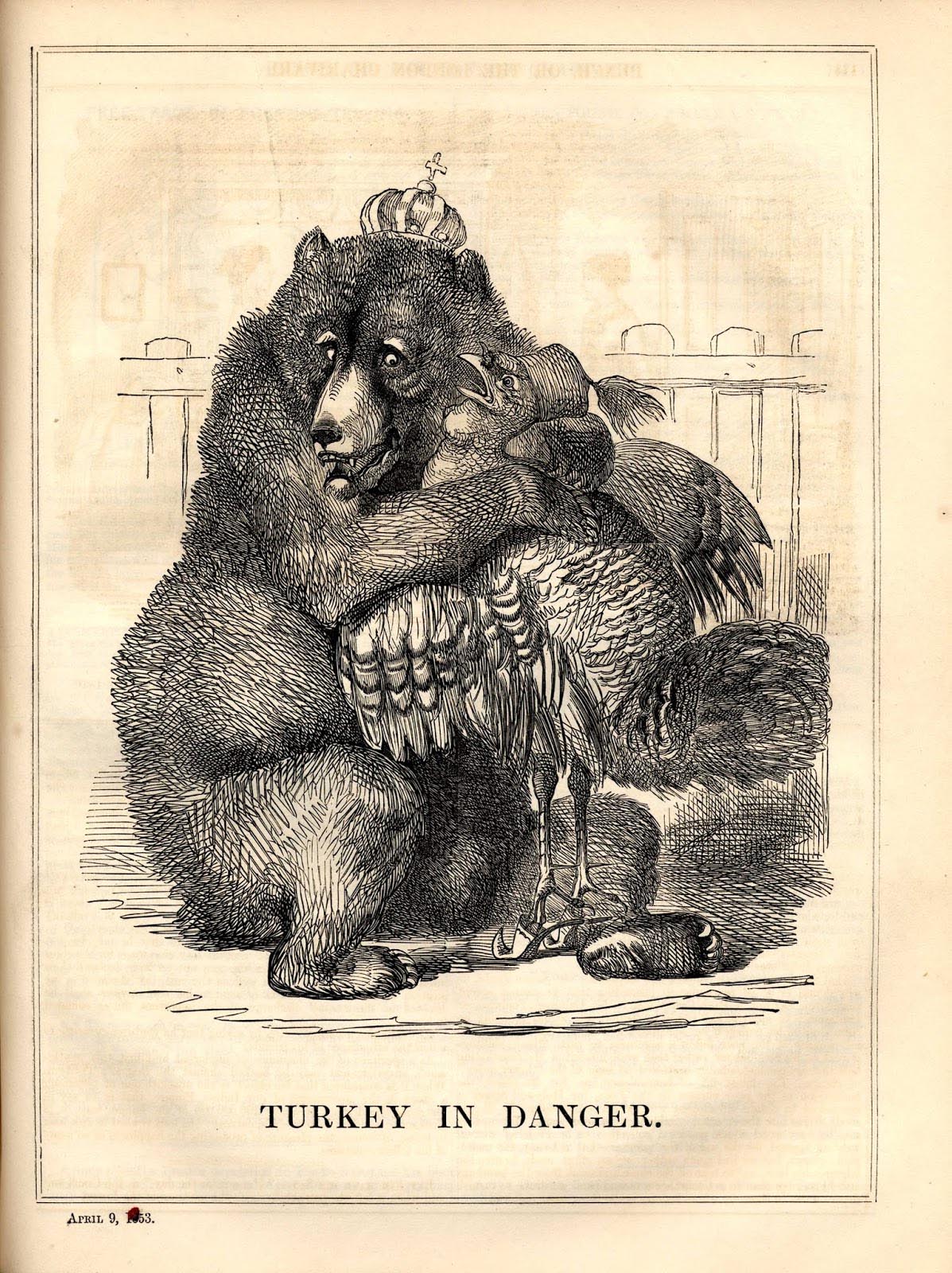

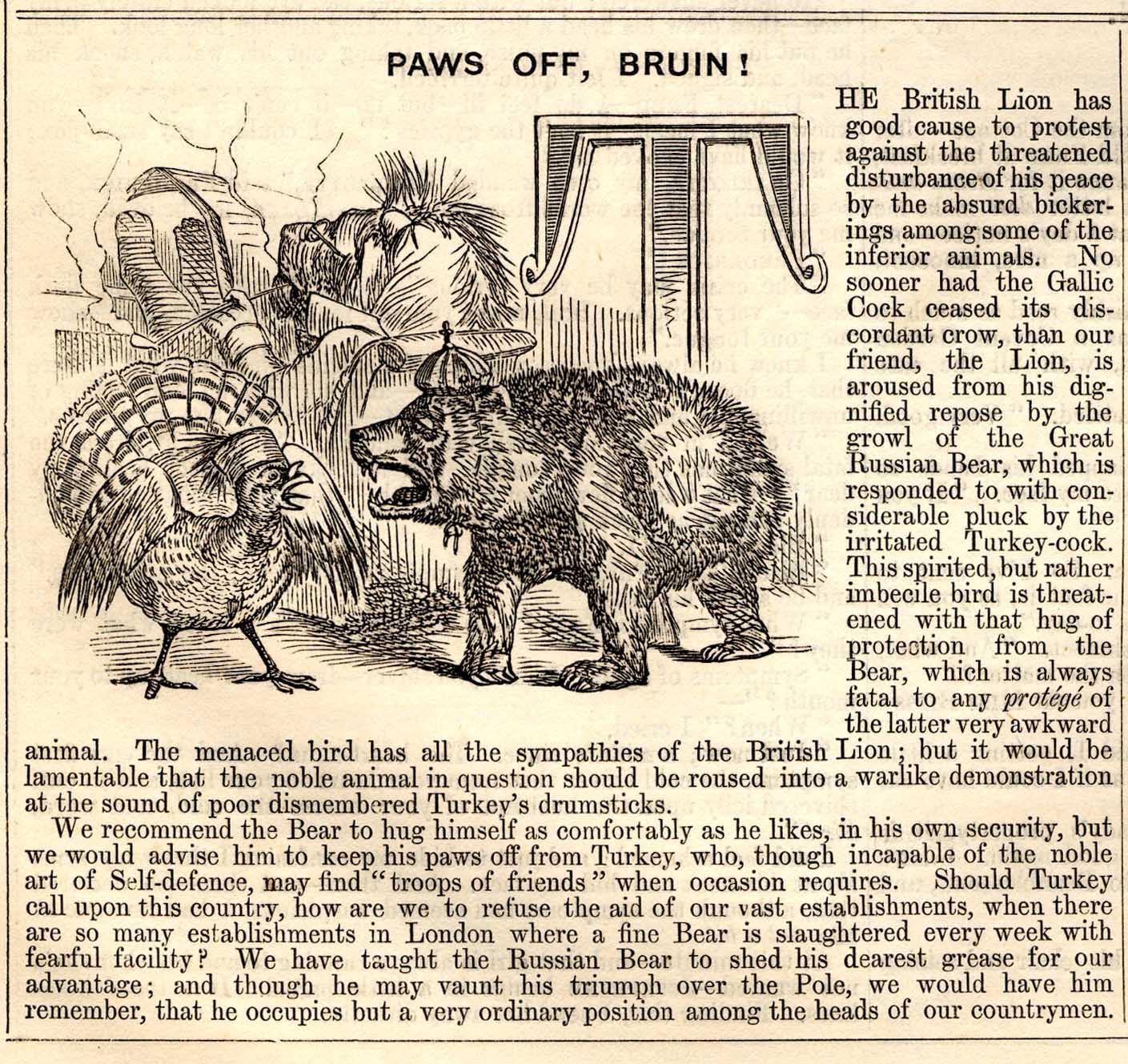

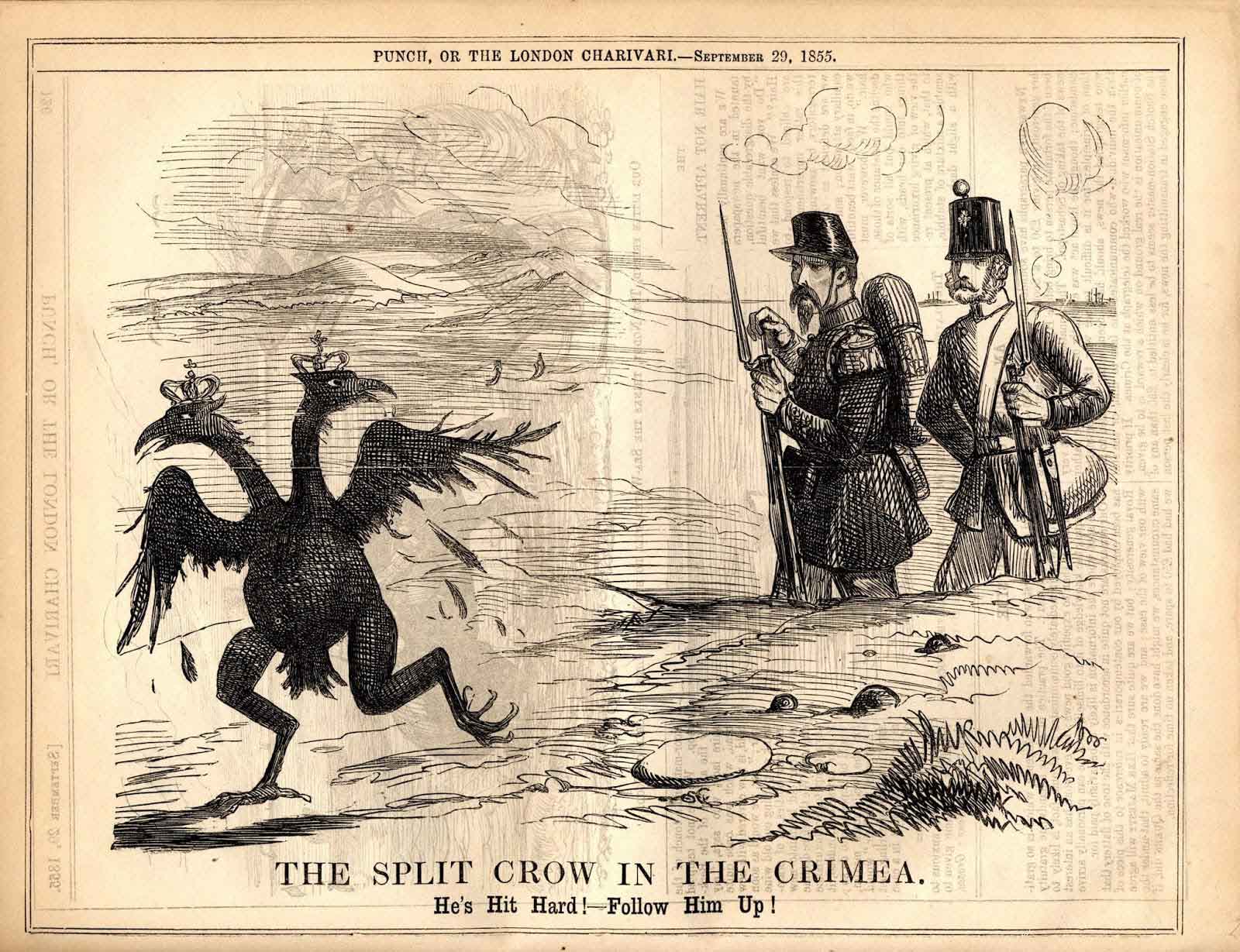

Turkey and the Russian Bear

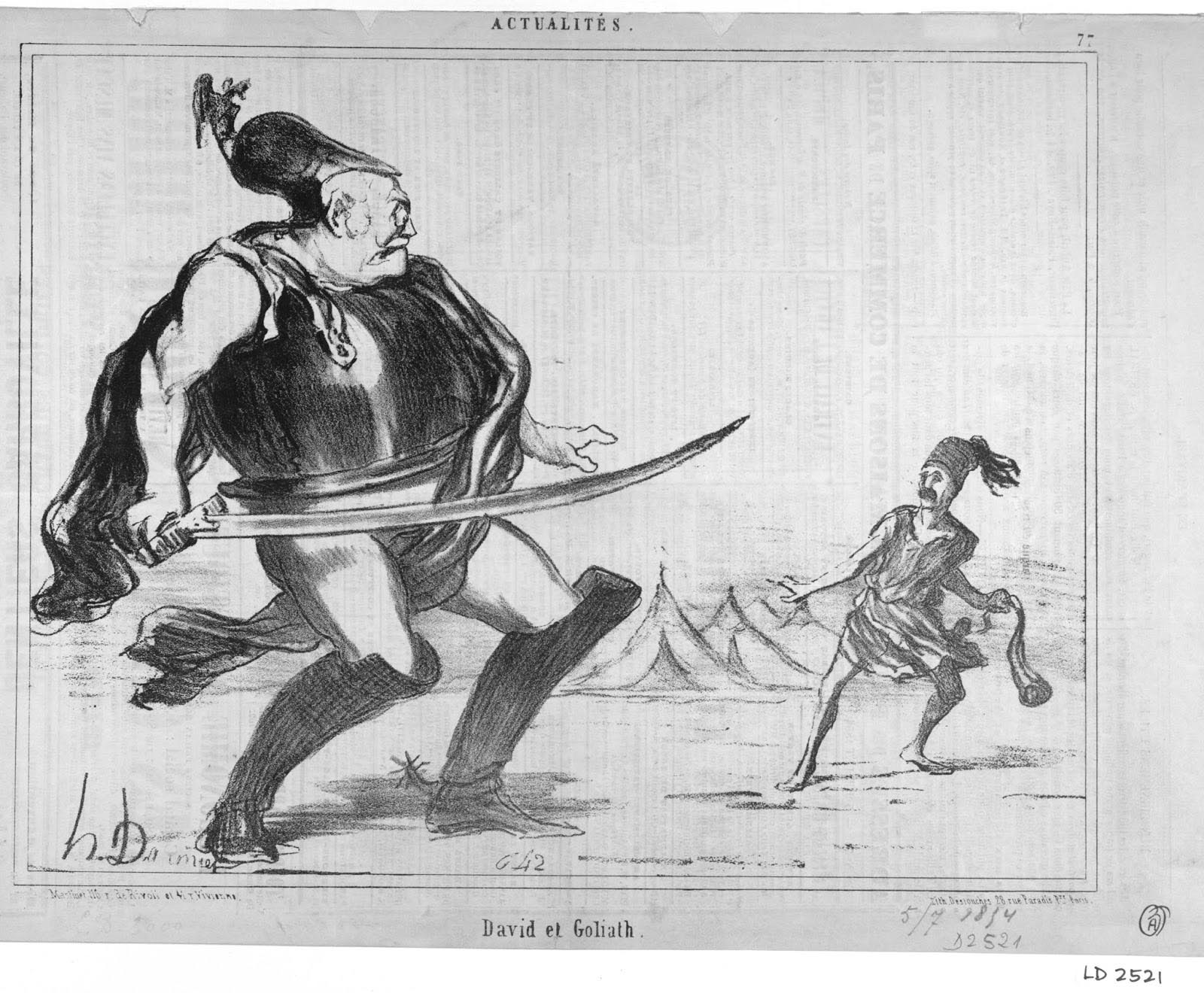

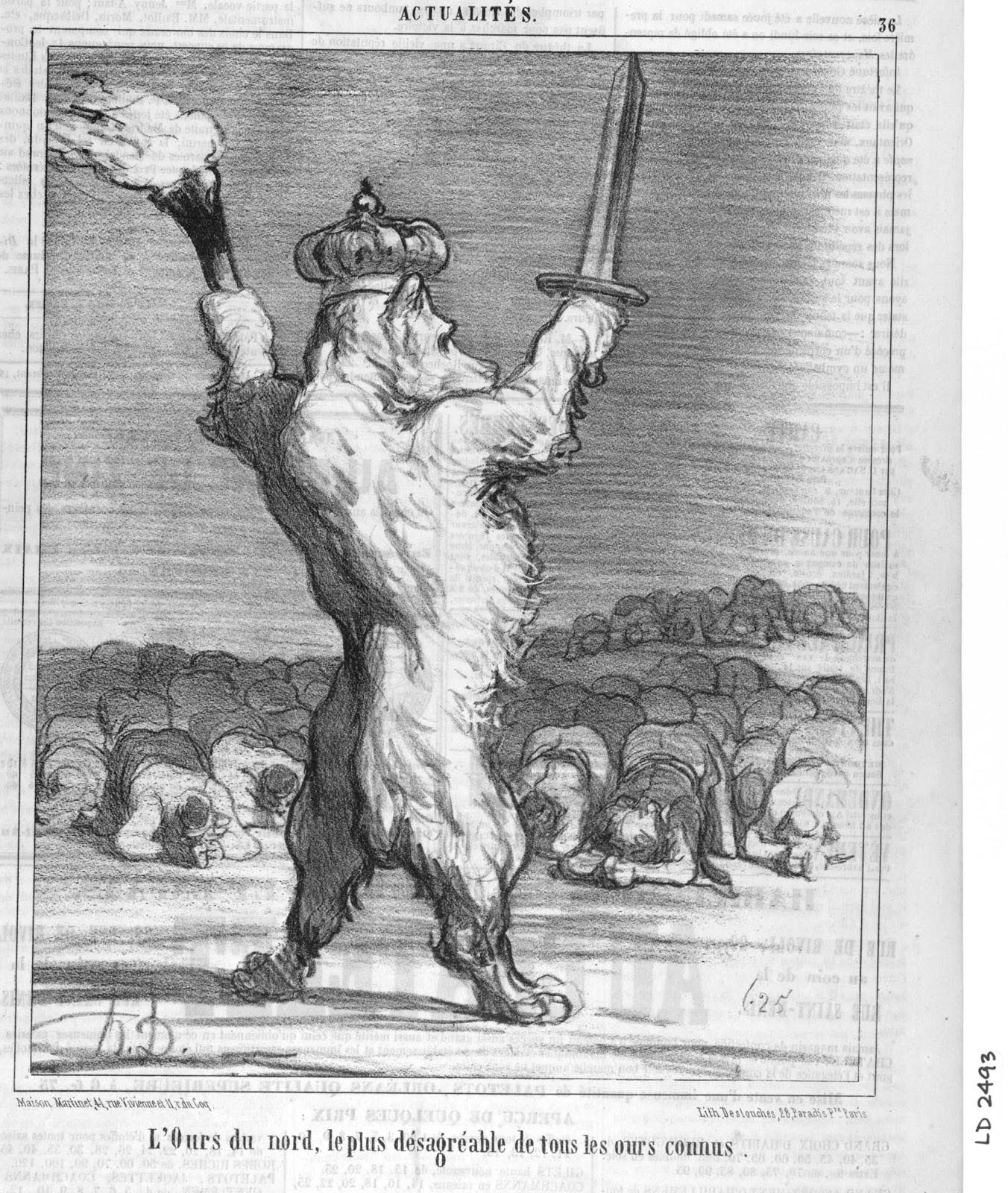

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 36; Chargeons les Russes (Let’s Make Caricatures of the Russians), no. 10. Le Charivari. April 17–18, 1854. LD 2493.

The bellicose Russian Bear as an autocrat with all of its subjects kneeling at its feet.

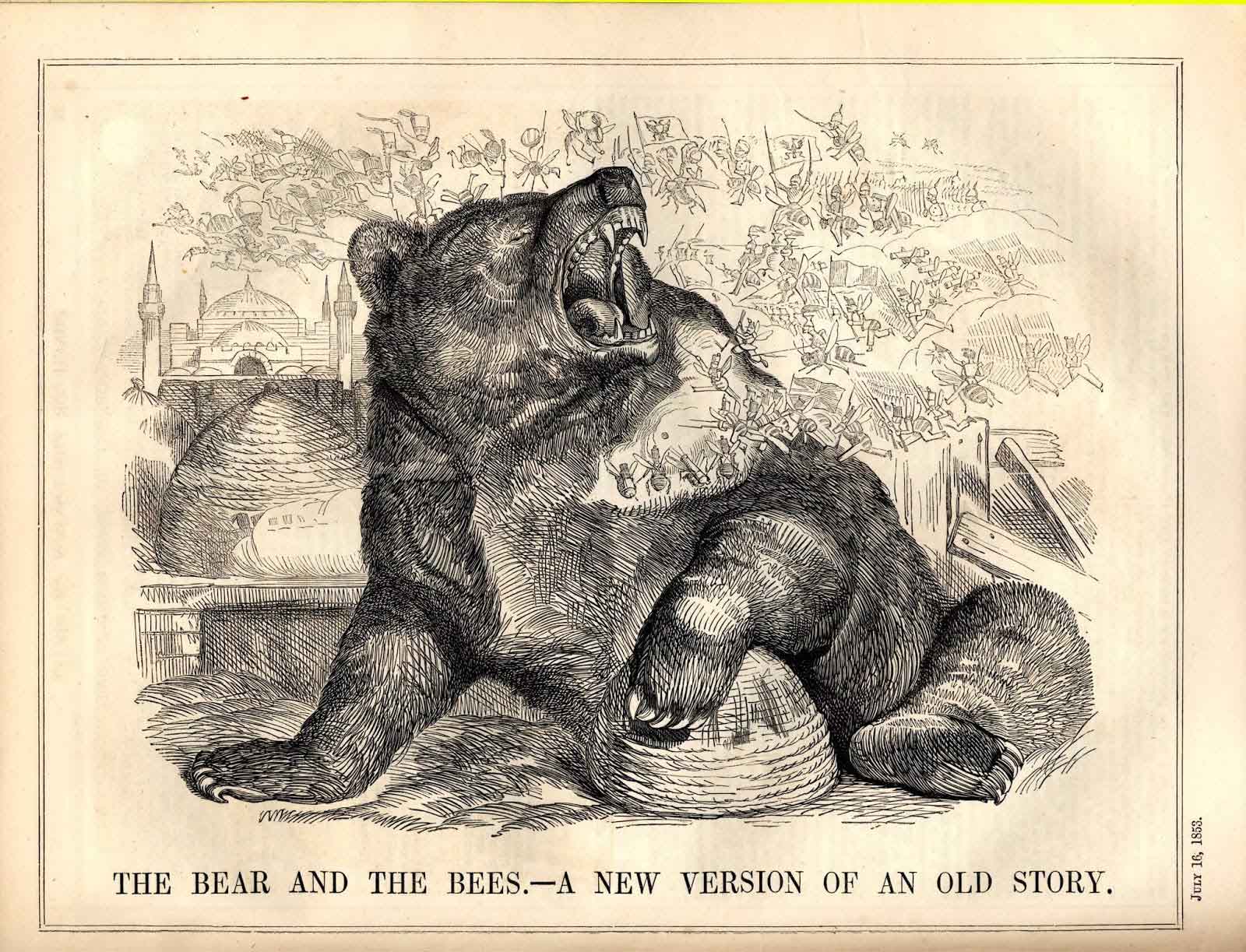

John Tenniel. Cartoon. Punch. July 16, 1853.

This print plays on an old folktale where a bear threatens to use his great strength against a hive of bees if they do not give him free honey. The bees refuse, and when the bear sticks his tongue in the hive to take the honey by force, the bees attack him, and their combined stings make the bear run away. Here, the Turks play the role of the bees — with their mosques resembling beehives — in beating back the advances of the Russian army on Turkish territory.

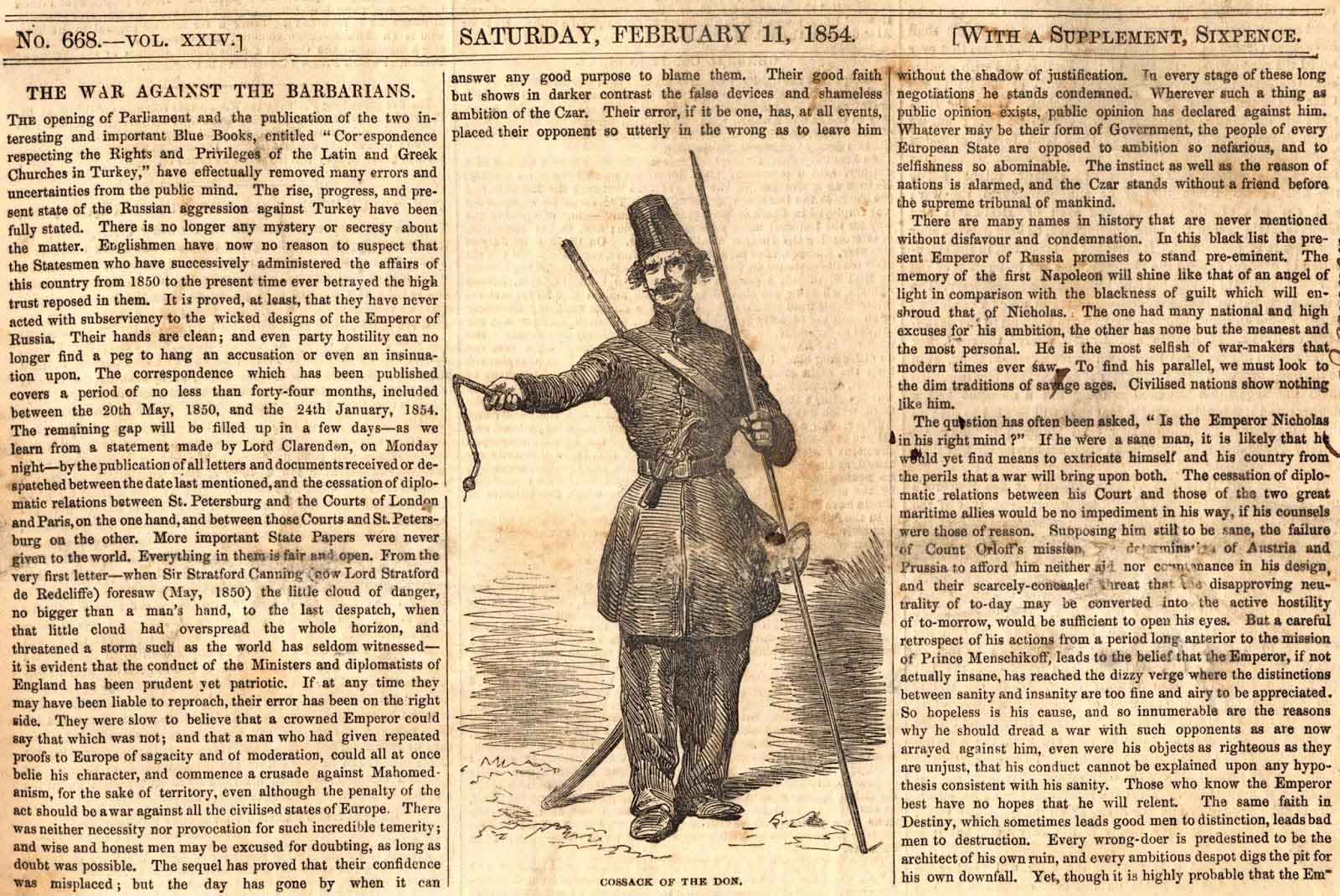

The Russian Cossacks

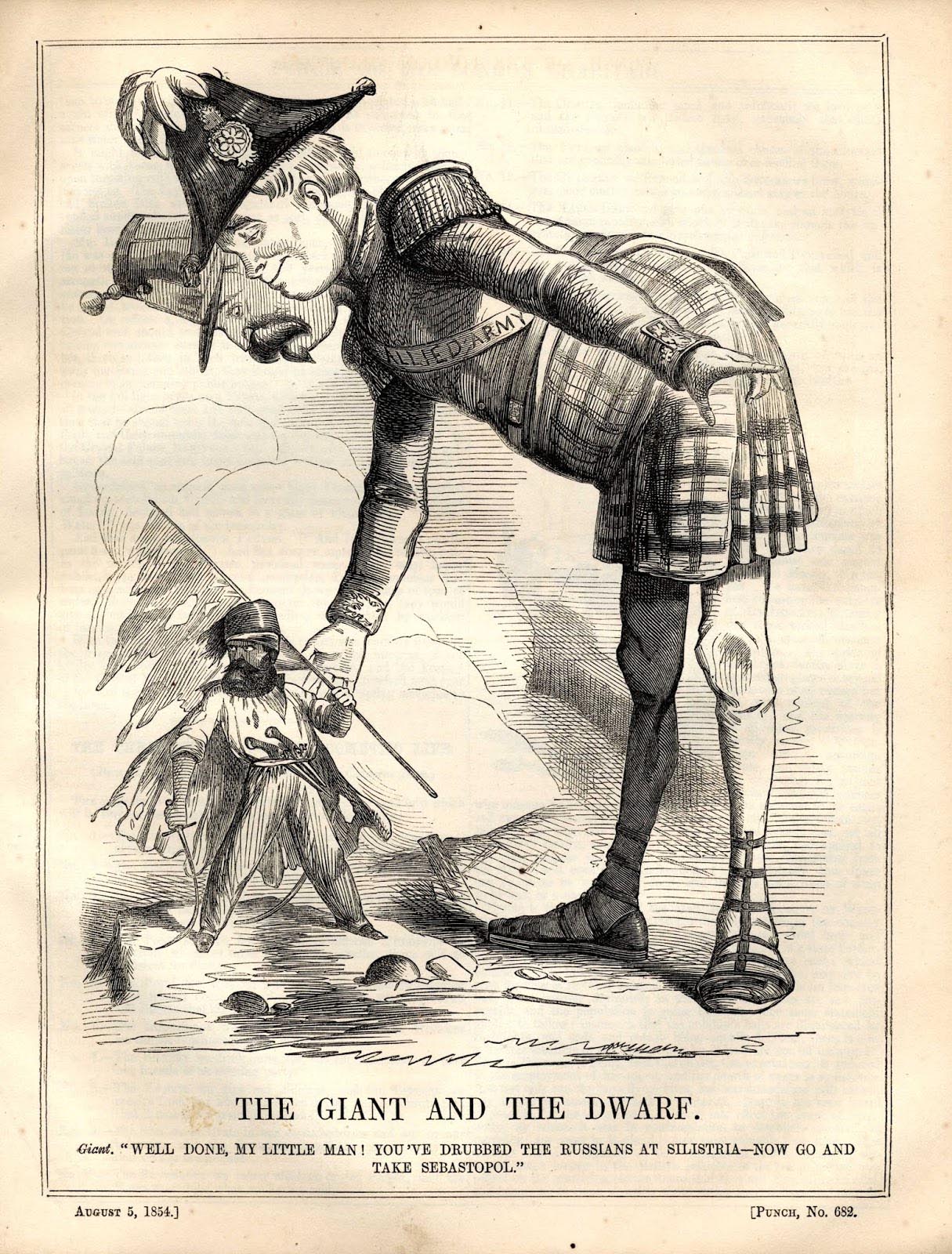

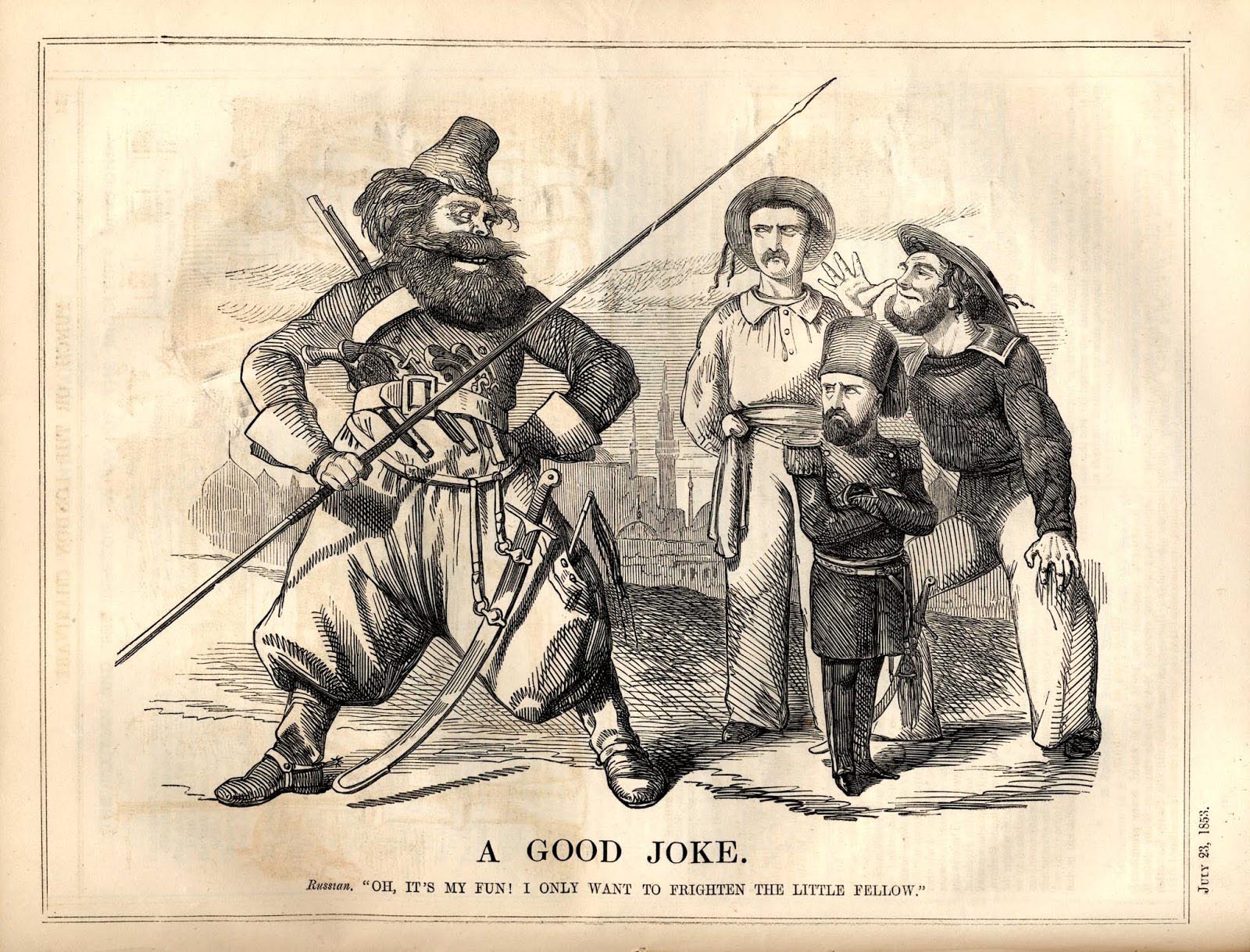

John Tenniel. Cartoon. Punch. July 23, 1853.

A heavily armed Russian Cossack soldier threateningly mocks a diminutive Turk, with French and British sailors standing in support behind him. After Russia invaded the Danubian Principalities, British and French fleets were positioned to aid Turkey in the event of war.

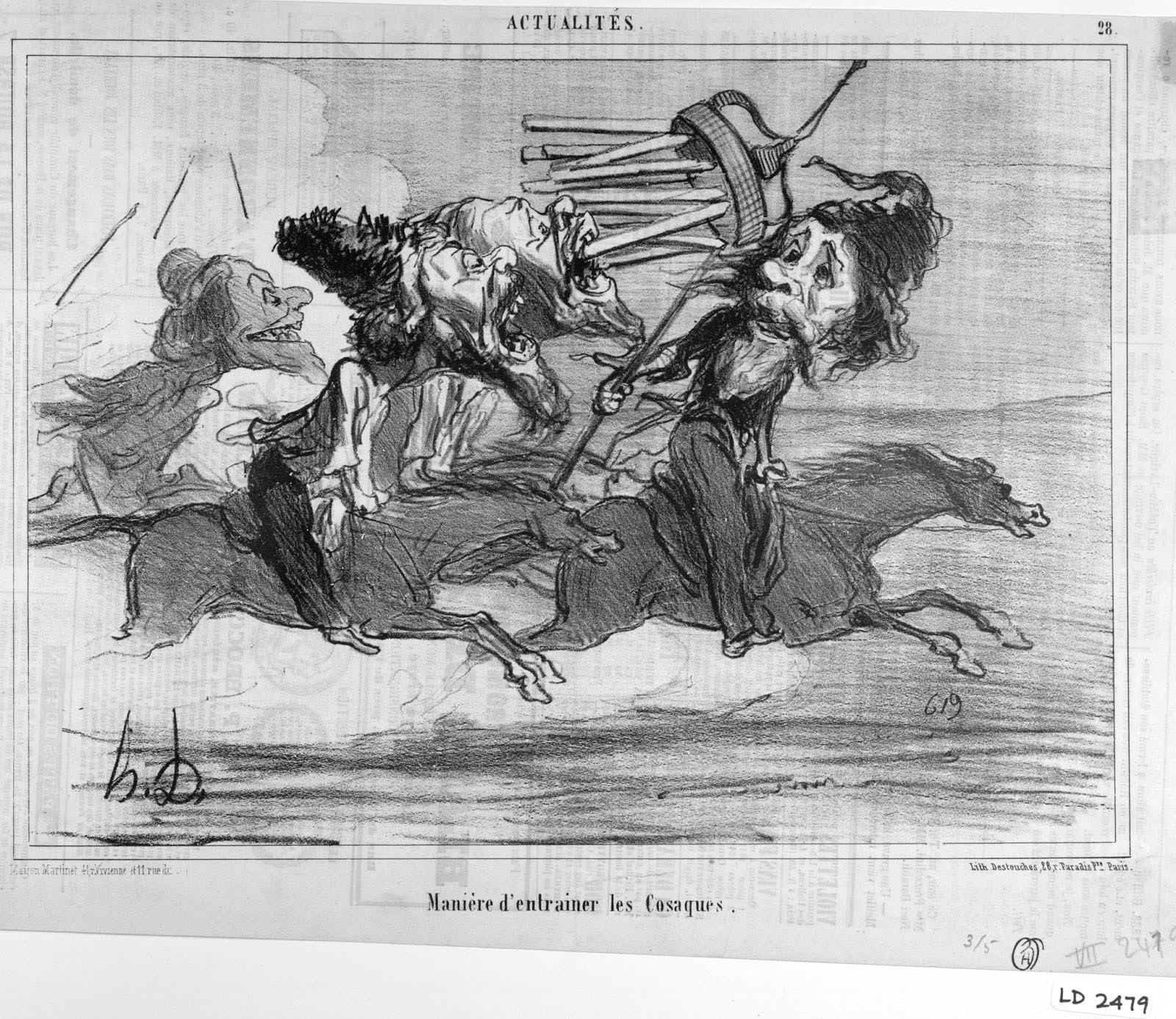

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 28; Les Cosaques pour rire (Laughing at the Cossacks), no. 16. Le Charivari. April 4, 1854. LD 2479.

With tensions between France and Russia running high, an old wives’ tale that Cossacks subsisted on candles surfaced, which Daumier played to the hilt with caricatures of uncouth, candle-eating Cossacks dominating several of his lithographs. Here, the Cossacks’ supposed hunger for candles spurs them on during a military training session.

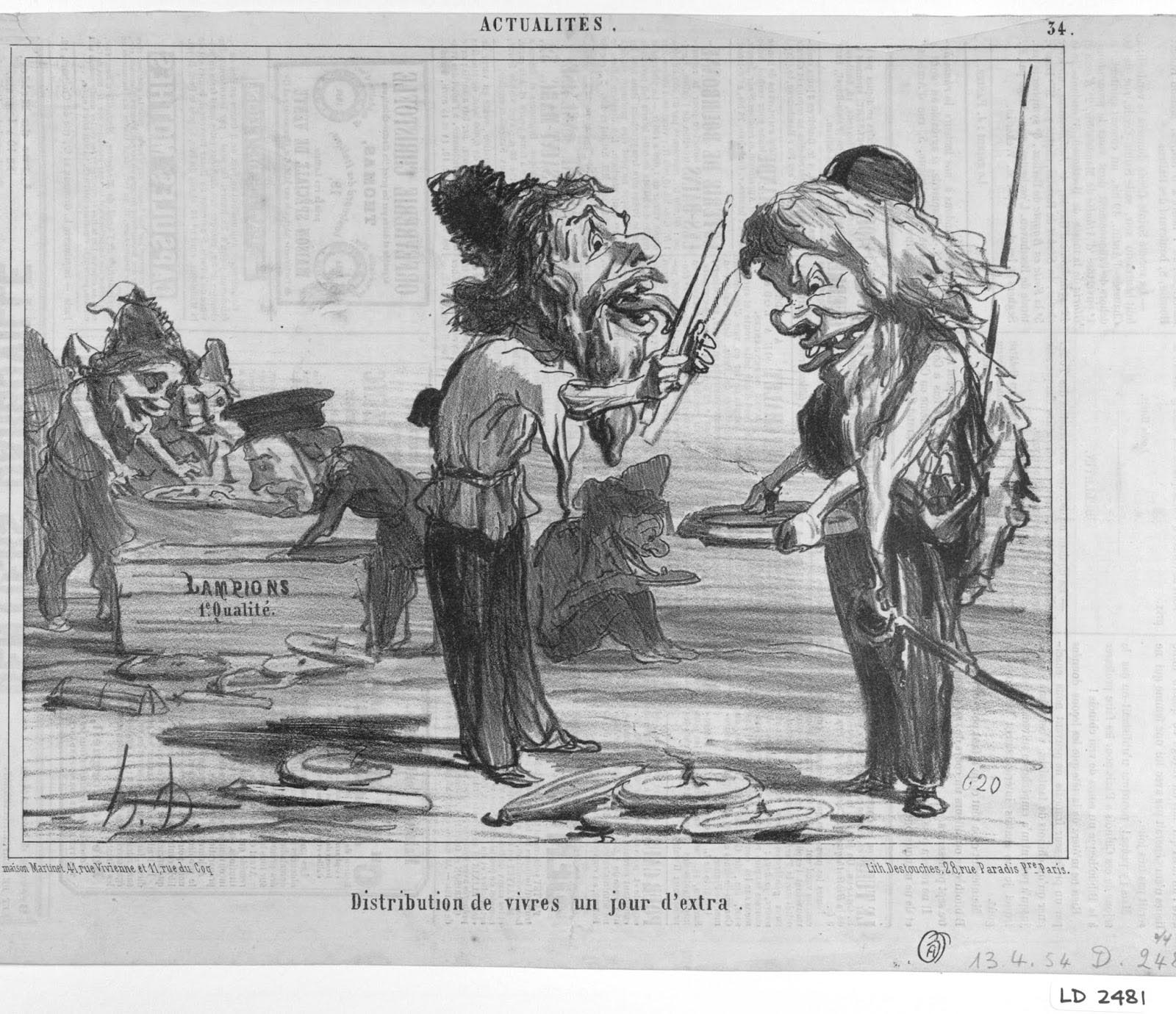

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 34; Les Cosaques pour rire (Laughing at the Cossacks), no. 20. Le Charivari. April 13, 1854. LD 2481.

The box in the background reads, “Top Quality Lampions” — flat, plate-shaped iron vessels filled with oil and wicks, perhaps booty from the conquered Danubian Principalities. The Cossack in the middle is licking his normal meal of candles, while his cohort on the right is salivating over his bonus lampion. Note the Cossack sitting in the background licking a lampion as if it were a plate or shallow bowl.

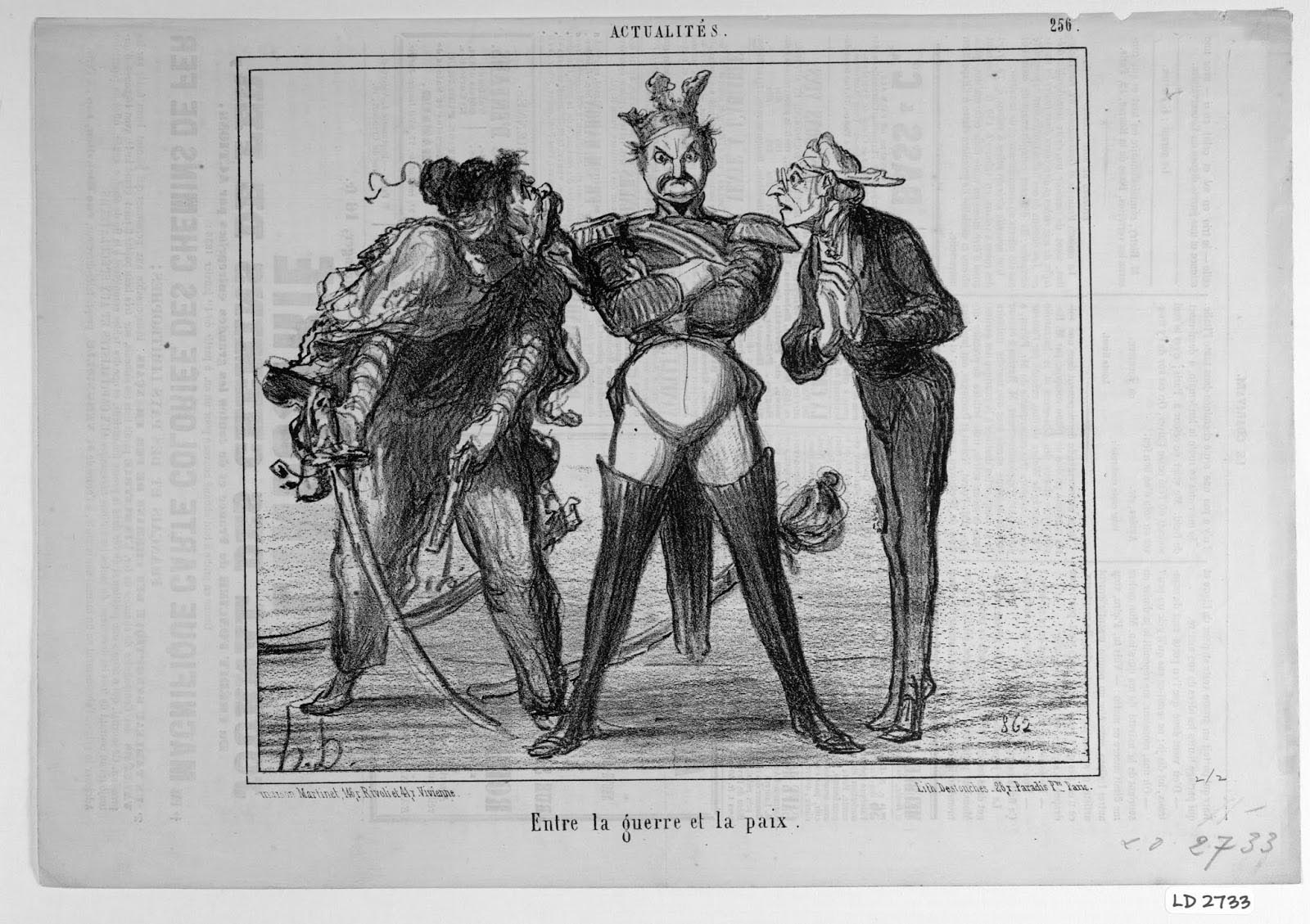

Negotiating the Peace

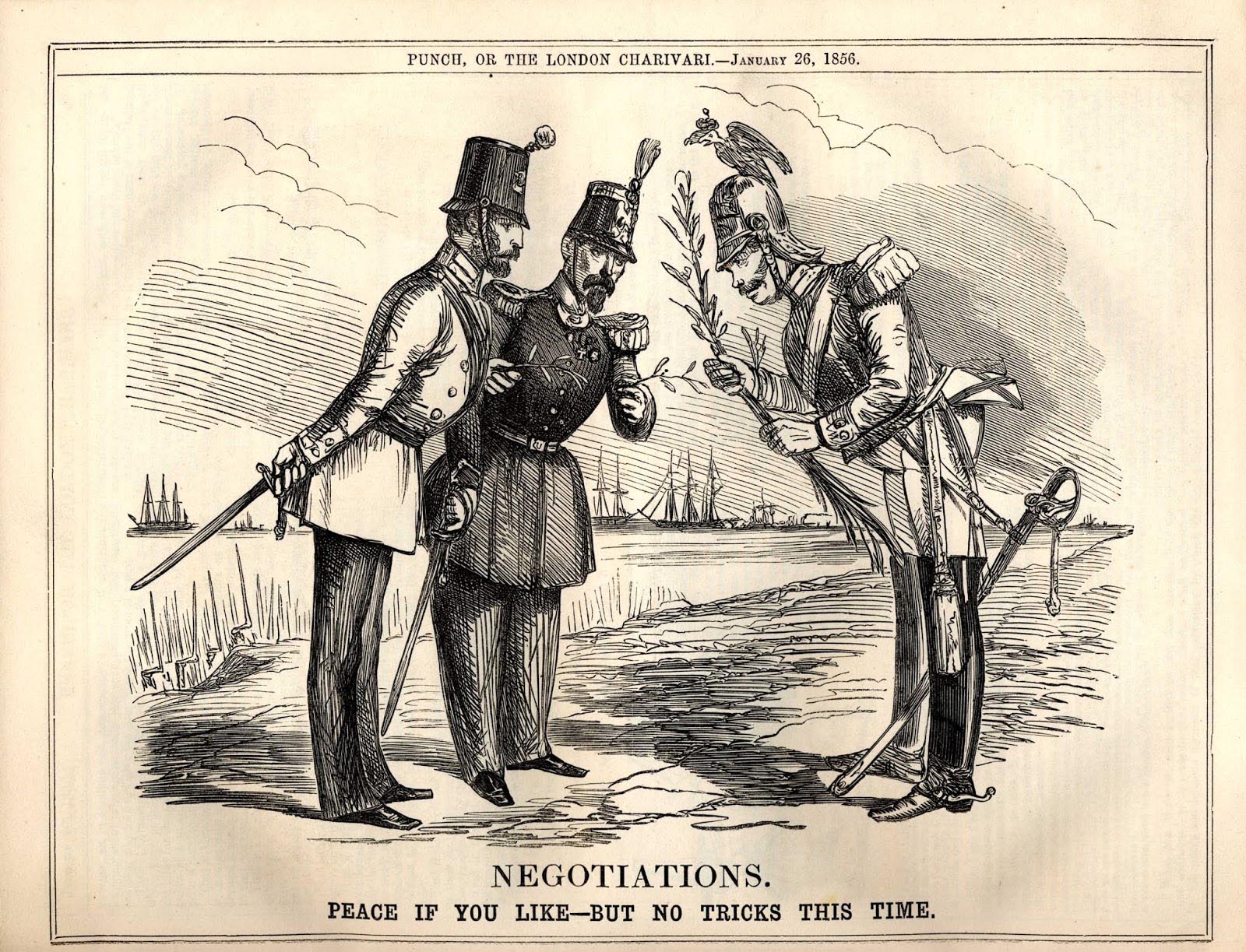

John Leech. Cartoon. Punch. January 26, 1856.

Czar Alexander II offers olive branches to French and British commanders, who are skeptical, given Russia’s expansionist tendencies. Nonetheless, the Treaty of Paris was signed on March 30, 1856. The Treaty lacked any mention of the Holy Places, which originally served as the supposed rationale for the war.

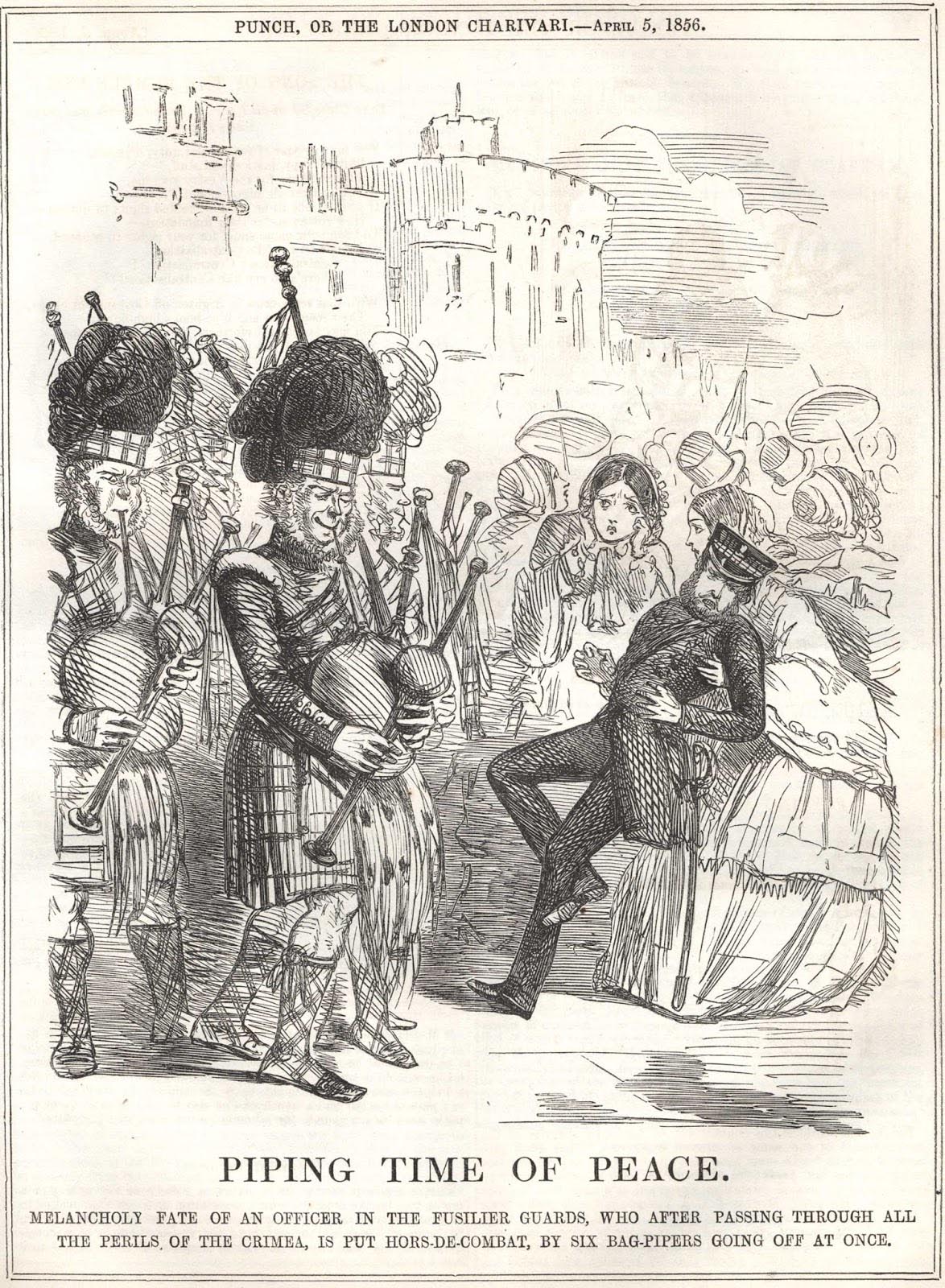

War’s Aftermath

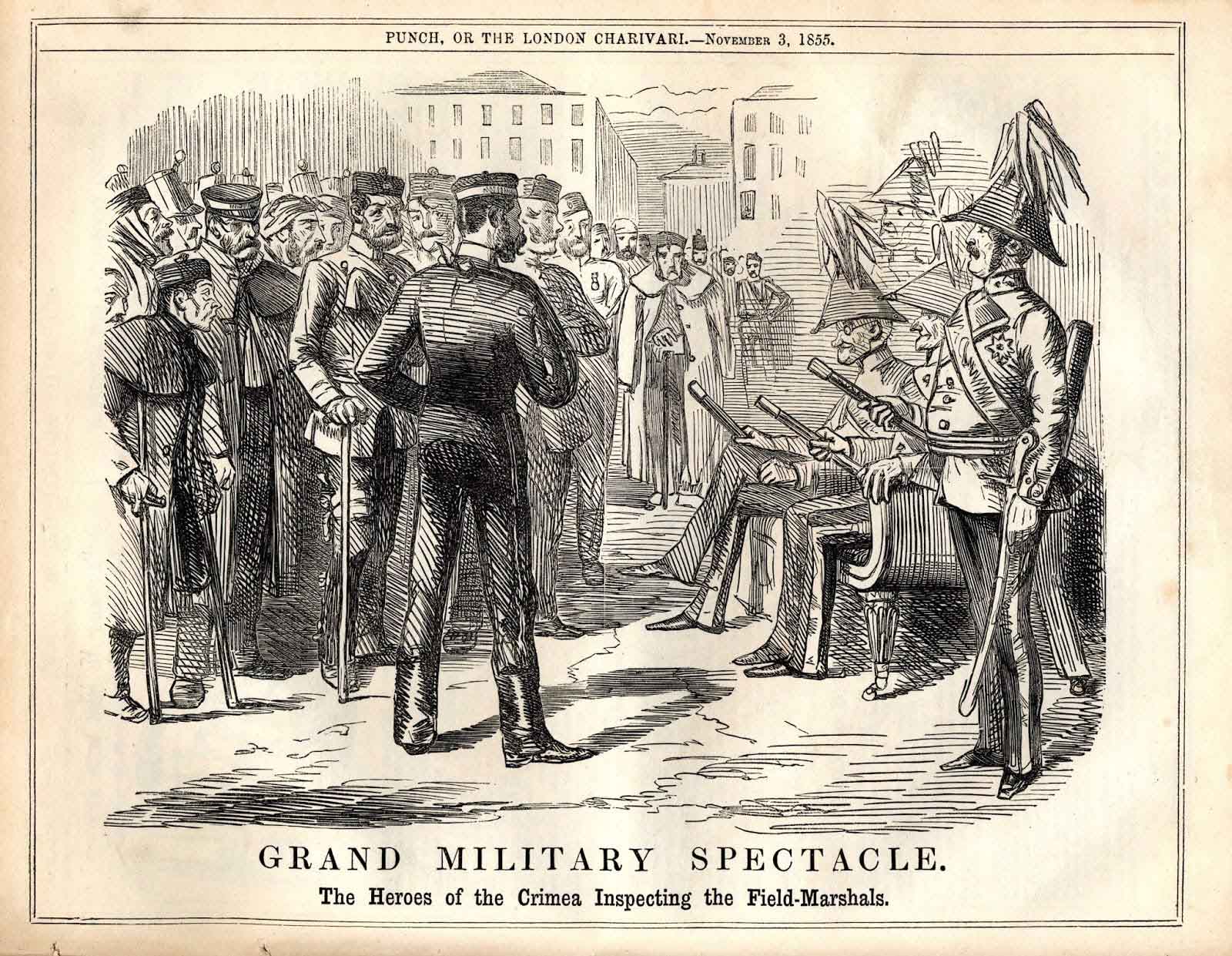

John Leech. Cartoon. Punch. November 3, 1855.

The British supply chain broke down during the winter of 1855/1856, creating appalling conditions for the soldiers on the field and in hospitals, while many British officers sought shelter in their yachts. The situation was immediately reported in the press and led to public outcry over the bungled military operations. Here, in a reversal of celebratory protocol, soldiers returning from the war — many injured — inspect the field-marshals, who appear none the worse for wear.

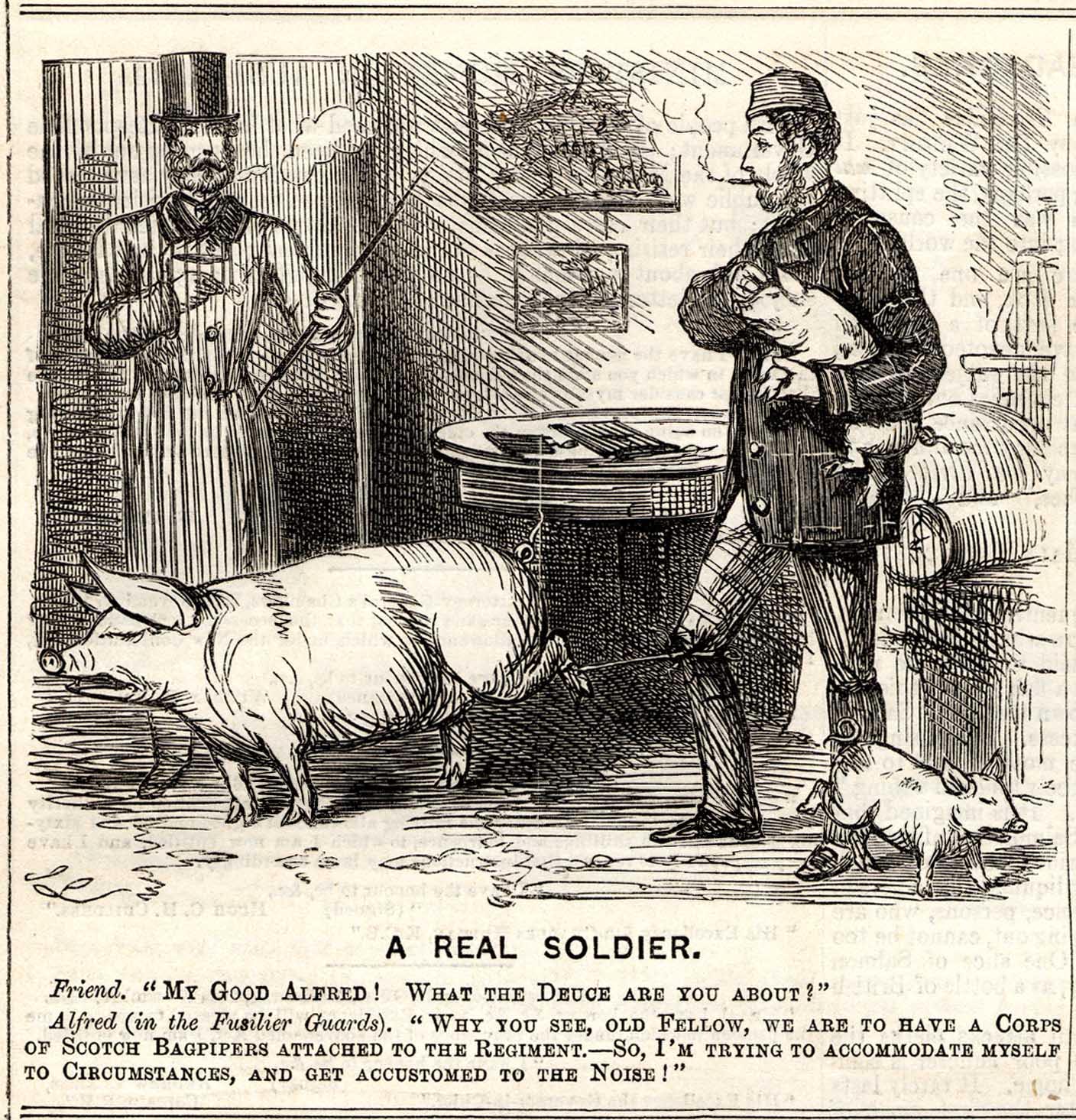

These two cartoons lampoon the use of ceremonial bagpipes to welcome soldiers returning home from the war. In the image on the right, a soldier ties squealing pigs to himself before attending a ceremony to help him adjust to the noise of the bagpipes.

John Leech. Cartoon. Punch. April 5, 1856.

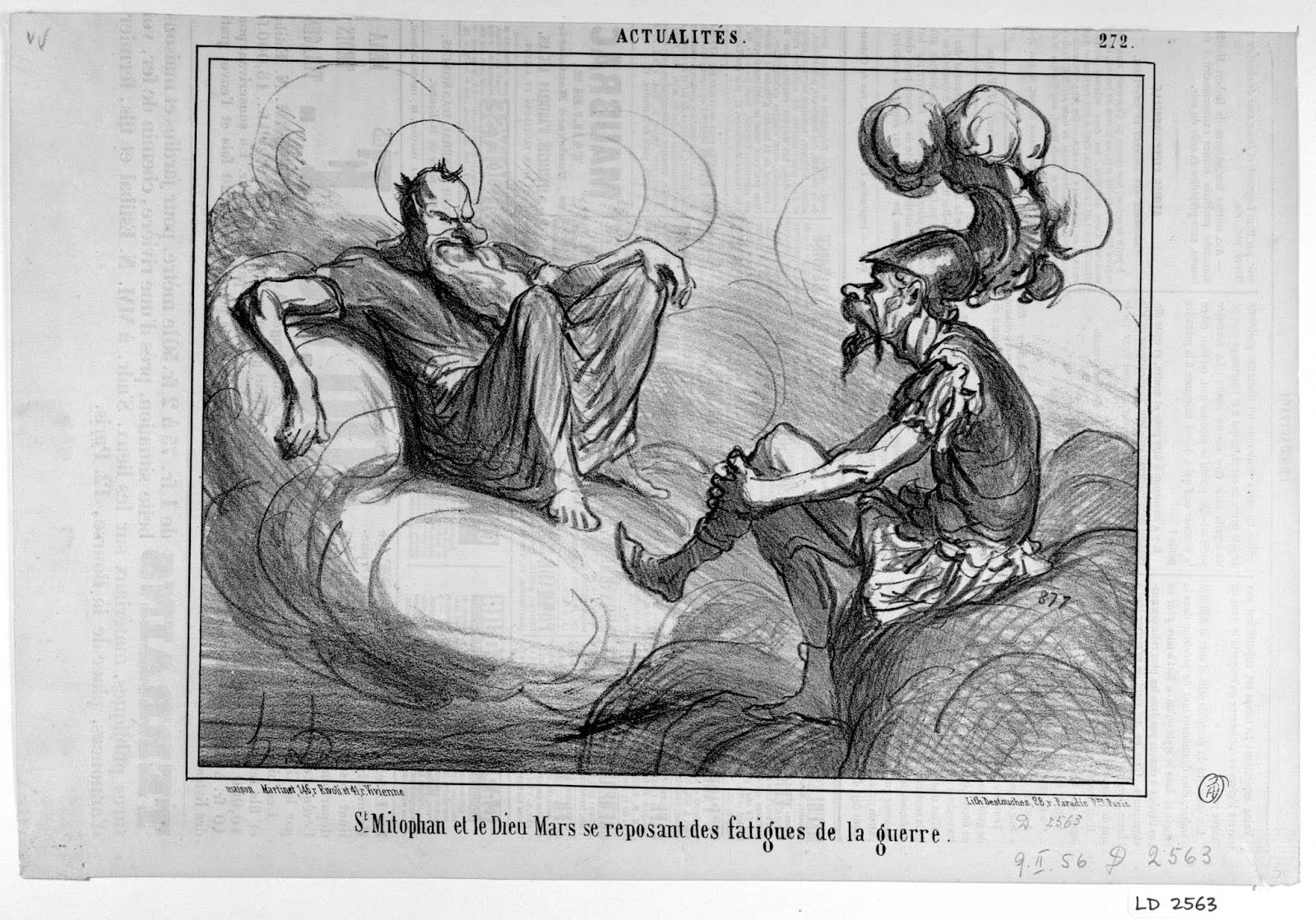

Honoré Daumier. Actualités, no. 272. Le Charivari. February 9, 1856. LD 2563.

St. Mitrophan of Voronezh (one of the Russian protector saints) and Mars (the god of war), exhausted from battle, rest on some clouds during the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris.