The Man Who Would Not Be Vice President: The Daniel Webster Collection

January 31, 2011

Description by Craig Bruce Smith, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in history

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department holds eleven manuscript boxes of the correspondence of famed American senator Daniel Webster. The letters, highly legible with clear script, provide an insightful behind-the-scenes look at dealings of 19th-century American politics. Daniel Webster was born in Salisbury, New Hampshire, on January 18, 1782, just a few months shy of the American Revolution’s Battle of Yorktown. He would go on to become one of the most well-known and esteemed politicians and lawyers of the 19th century. Webster represents a generation of Americans who grew up in the recently independent United States, came of age well after the Revolution, and sought to live up to the image of the Founding Fathers. He would celebrate his second birthday four months after the 1783 Peace of Paris officially ended the war, but his later diplomatic work would come to finalize this treaty.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department holds eleven manuscript boxes of the correspondence of famed American senator Daniel Webster. The letters, highly legible with clear script, provide an insightful behind-the-scenes look at dealings of 19th-century American politics. Daniel Webster was born in Salisbury, New Hampshire, on January 18, 1782, just a few months shy of the American Revolution’s Battle of Yorktown. He would go on to become one of the most well-known and esteemed politicians and lawyers of the 19th century. Webster represents a generation of Americans who grew up in the recently independent United States, came of age well after the Revolution, and sought to live up to the image of the Founding Fathers. He would celebrate his second birthday four months after the 1783 Peace of Paris officially ended the war, but his later diplomatic work would come to finalize this treaty.

Educated at Dartmouth College, Webster developed a skill for oratory, a Federalist political persuasion, and a continued exaltation for the memory of George Washington as a “political saviour.”[1] After graduation he began his study of the law, first under Thomas W. Thompson and then later Christopher Gore—the first United States attorney and future governor of Massachusetts (whose estate is located less than three miles from Brandeis University)—before being admitted to the bar in 1805. Webster became a prominent attorney, arguing over two hundred cases before the United States Supreme Court alone—including his notable victories in Dartmouth v. Woodward and McCulloch v. Maryland. In politics, Webster held three separate elected positions in the Congress; his time in Washington continued to reflect his Federalist ideals and gift for public speaking. He served in the House as the Representative for New Hampshire (1813-1817) and Massachusetts (1823-1827). Following his time there, Webster was then elected as a senator for Massachusetts and served on two separate occasions (1827-1841 and 1845-1850). In 1841, Webster was appointed Secretary of State by President William Henry Harrison, partly as a reward for the support provided by Massachusetts during the campaign and election.[2]

Educated at Dartmouth College, Webster developed a skill for oratory, a Federalist political persuasion, and a continued exaltation for the memory of George Washington as a “political saviour.”[1] After graduation he began his study of the law, first under Thomas W. Thompson and then later Christopher Gore—the first United States attorney and future governor of Massachusetts (whose estate is located less than three miles from Brandeis University)—before being admitted to the bar in 1805. Webster became a prominent attorney, arguing over two hundred cases before the United States Supreme Court alone—including his notable victories in Dartmouth v. Woodward and McCulloch v. Maryland. In politics, Webster held three separate elected positions in the Congress; his time in Washington continued to reflect his Federalist ideals and gift for public speaking. He served in the House as the Representative for New Hampshire (1813-1817) and Massachusetts (1823-1827). Following his time there, Webster was then elected as a senator for Massachusetts and served on two separate occasions (1827-1841 and 1845-1850). In 1841, Webster was appointed Secretary of State by President William Henry Harrison, partly as a reward for the support provided by Massachusetts during the campaign and election.[2]

The bulk of Brandeis University’s Daniel Webster collection consists of correspondence composed and received during his time in the Cabinet, much of which is not available in published form. The vast majority of Webster’s correspondence deals with appointments for both domestic and international offices—ranging from the marshalship for the middle district of Tennessee to the consulate of Amsterdam. Naturally, the correspondence represents a transitional period between presidencies.

The bulk of Brandeis University’s Daniel Webster collection consists of correspondence composed and received during his time in the Cabinet, much of which is not available in published form. The vast majority of Webster’s correspondence deals with appointments for both domestic and international offices—ranging from the marshalship for the middle district of Tennessee to the consulate of Amsterdam. Naturally, the correspondence represents a transitional period between presidencies.

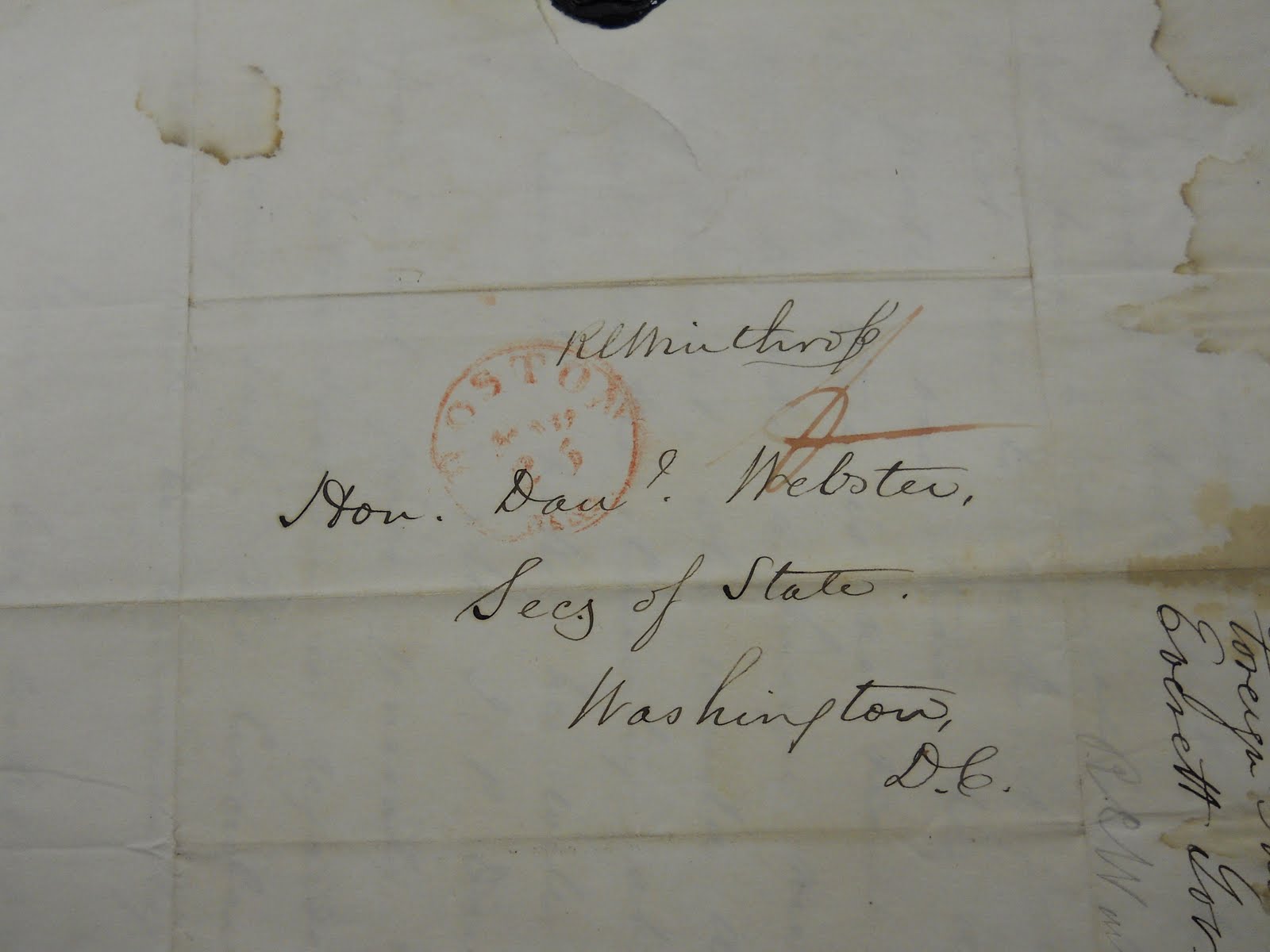

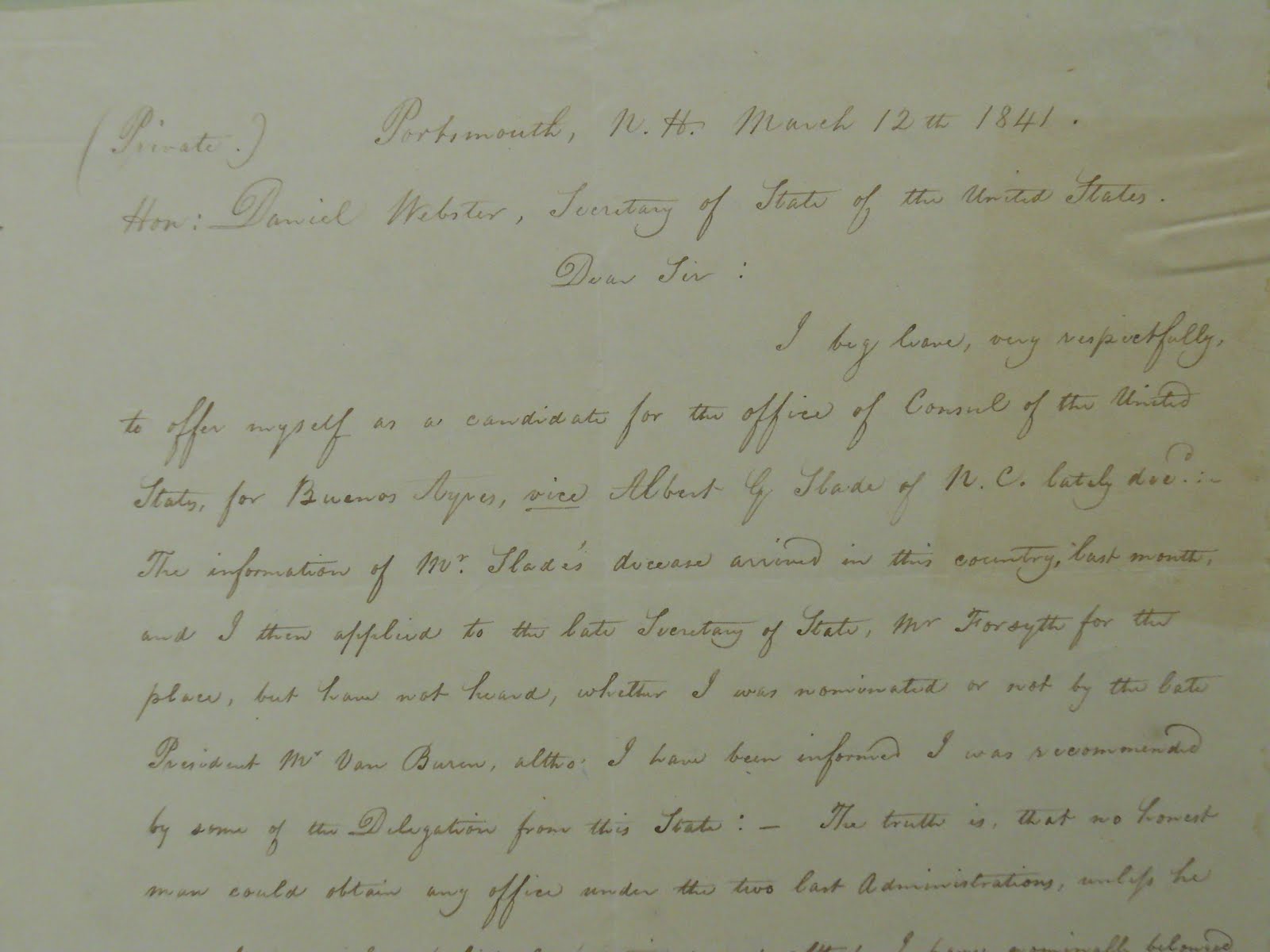

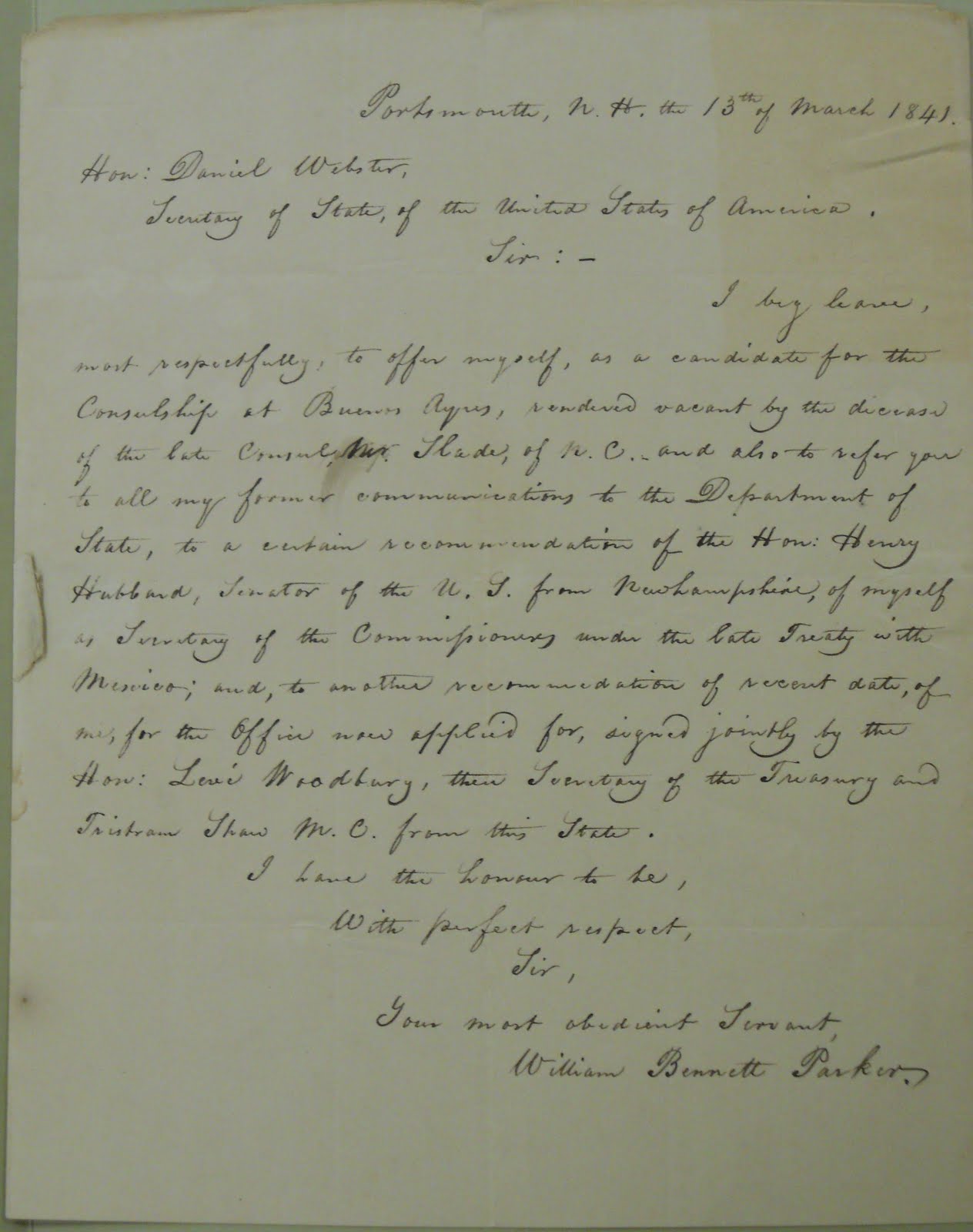

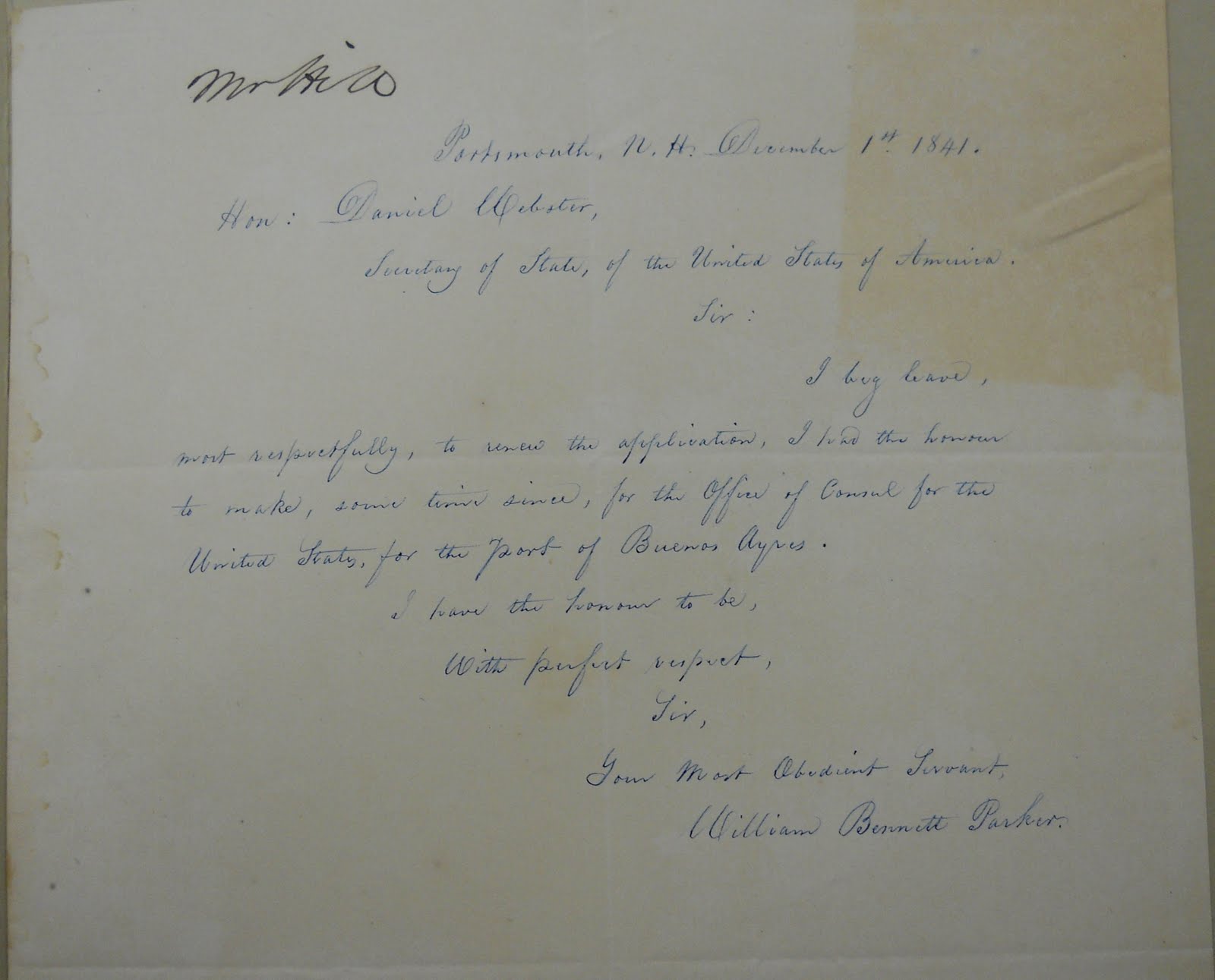

Three types of correspondence dominate the collection: letters of recommendation from third parties extol the virtues of prospective government employees; handwritten applications in essay format allow statements of personal credentials; and the currently-employed penned notes seeking to retain their jobs.[3] The collection reveals a great deal of action surrounding the application process, particularly for the consulate of Buenos Aires. While most applicants opted for letters of recommendation, William Bennett Parker, a former record keeper for the Bank of the United States, eagerly applied directly to Webster six times (the first two letters sent barely a day apart) for the position, citing among his desirable skills the ability “to read with facility [Don Quixote in the original.”[4]

The genre of these letters is particularly interesting, as the Whig Party had promised to abandon the “spoils system” of the Jacksonian Era in favor of advancement by merit alone. William Parker, the avid petitioner and Democrat, wrote that “The truth is that no honest man could obtain any office under the two last Administrations, unless he was, also, a violent political partisan.”[5] However, Webster’s correspondence illustrates that “the Whig ascendancy did not mean the end of the patronage system.”[6] Letter after letter recommends various individuals for posts within the U.S. government around the world. Yet some stand out more than others as potential examples of patronage. During his early days as Secretary of State, Webster managed to clear a large portion of his debt of over one hundred thousand dollars, due in part to the fact that he “sold diplomatic appointments.”[7]

The genre of these letters is particularly interesting, as the Whig Party had promised to abandon the “spoils system” of the Jacksonian Era in favor of advancement by merit alone. William Parker, the avid petitioner and Democrat, wrote that “The truth is that no honest man could obtain any office under the two last Administrations, unless he was, also, a violent political partisan.”[5] However, Webster’s correspondence illustrates that “the Whig ascendancy did not mean the end of the patronage system.”[6] Letter after letter recommends various individuals for posts within the U.S. government around the world. Yet some stand out more than others as potential examples of patronage. During his early days as Secretary of State, Webster managed to clear a large portion of his debt of over one hundred thousand dollars, due in part to the fact that he “sold diplomatic appointments.”[7]

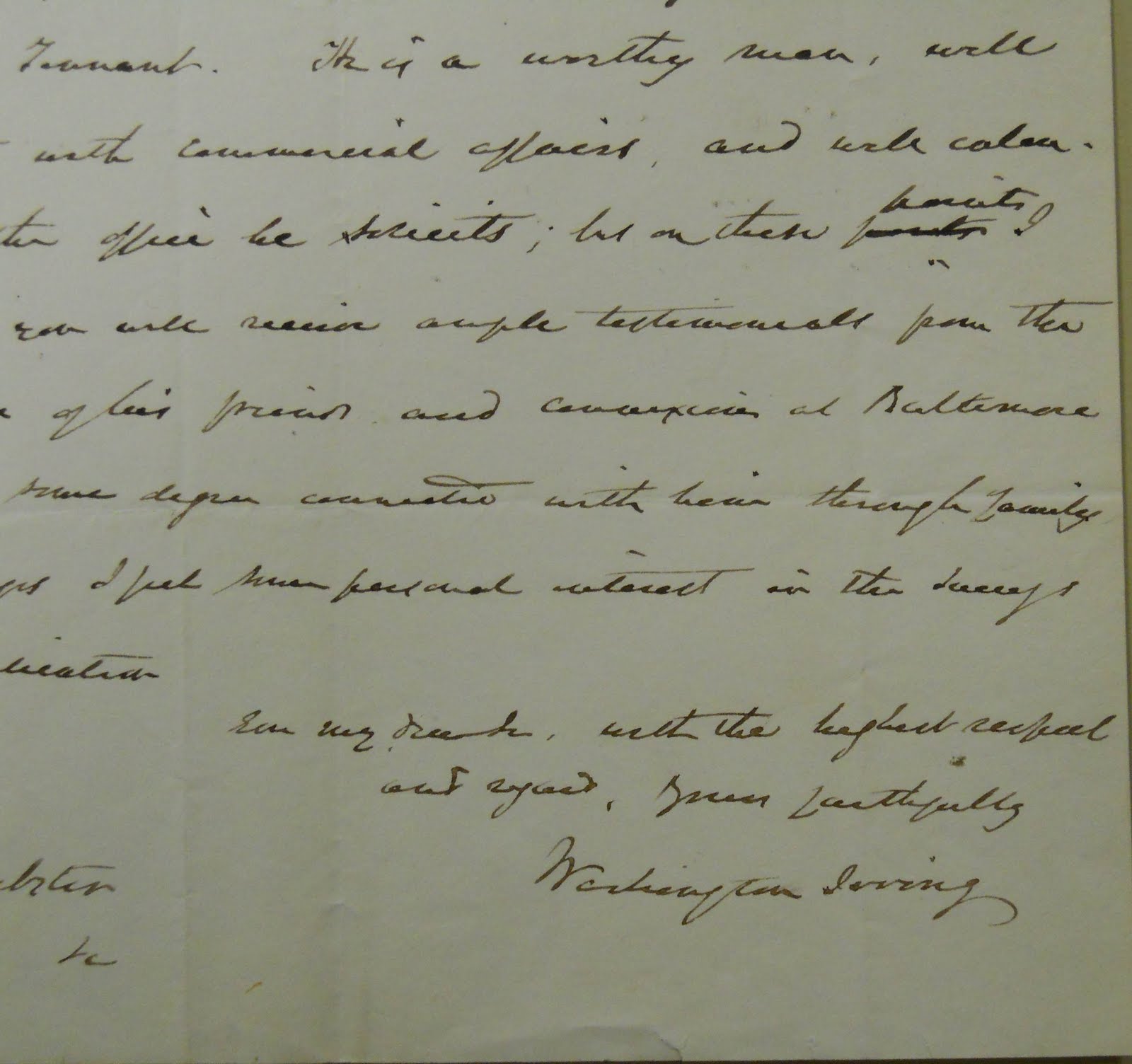

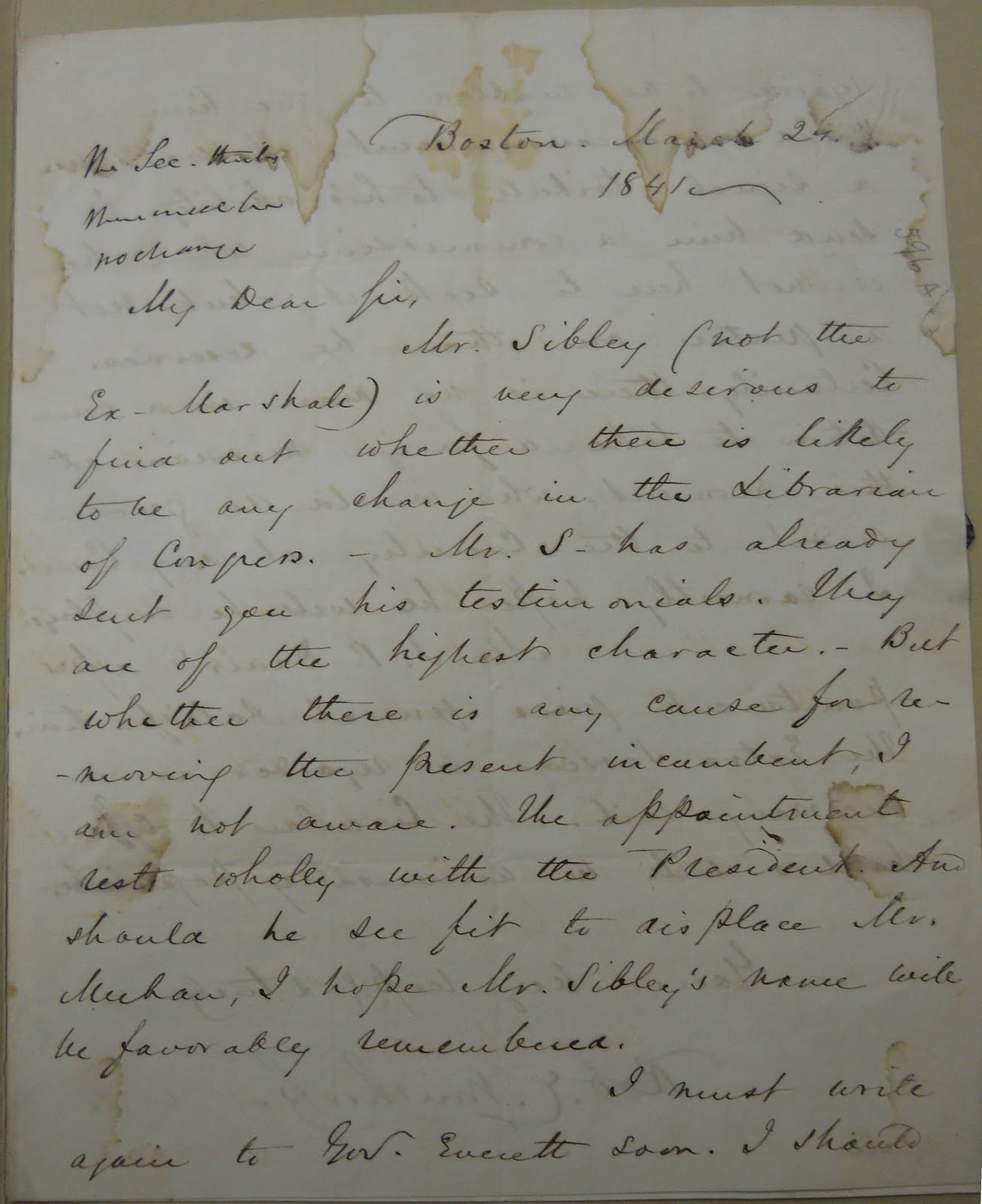

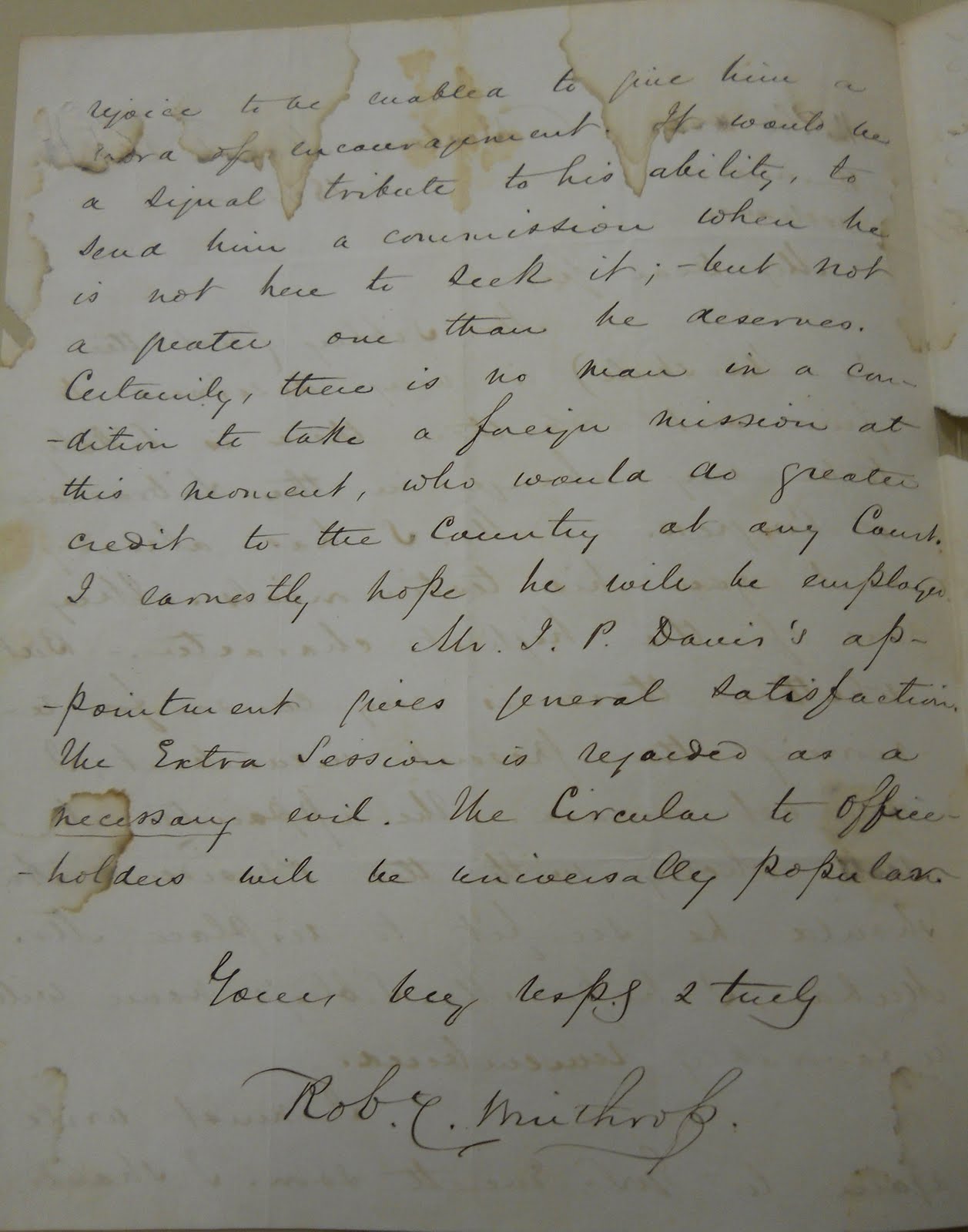

Though not unqualified, Washington Irving, the author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” was made minister to Spain in exchange for a forgiveness of a debt on mortgaged property.[8] Irving in turn would use his influence to recommend others for diplomatic posts.[9] Irving described Thomas B. Adain, a prospective diplomat, as “a worthy man, well acquainted with commercial affairs” in his relatively vague recommendation for the position of consul to Belfast, Ireland.[10] In addition, political ally Congressman Robert C. Winthrop, the future Speaker of the House of Representatives, urged Webster to grant Edward Everett, the former Massachusetts governor, a diplomatic commission as “there is no man in a condition to take a foreign mission at this moment, who would do greater credit to his Country at any Court.”[11] The part such a recommendation played is debatable, but, combined with Everett’s previous fund raising for Webster’s campaigns, it was more than enough to secure him the ambassadorship to Great Britain.[12]

Though not unqualified, Washington Irving, the author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” was made minister to Spain in exchange for a forgiveness of a debt on mortgaged property.[8] Irving in turn would use his influence to recommend others for diplomatic posts.[9] Irving described Thomas B. Adain, a prospective diplomat, as “a worthy man, well acquainted with commercial affairs” in his relatively vague recommendation for the position of consul to Belfast, Ireland.[10] In addition, political ally Congressman Robert C. Winthrop, the future Speaker of the House of Representatives, urged Webster to grant Edward Everett, the former Massachusetts governor, a diplomatic commission as “there is no man in a condition to take a foreign mission at this moment, who would do greater credit to his Country at any Court.”[11] The part such a recommendation played is debatable, but, combined with Everett’s previous fund raising for Webster’s campaigns, it was more than enough to secure him the ambassadorship to Great Britain.[12]

After President William Henry Harrison died one month into his term, Webster held the auspicious title of being the secretary of state under the shortest presidential administration in American history. In addition, he has the even more dubious distinction of turning down the office of vice president under Harrison, who was the first president to die in office, because he viewed it as beneath him.[13] As an ironic conciliatory prize, Webster served as “acting President” for two days until Vice President John Tyler arrived in Washington, D.C., to assume the position from the fallen Harrison.[14] Webster retained his post under Tyler until he resigned in 1843. The culmination of his efforts in the State Department reached its pinnacle with the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which eased decades of hostility with Great Britain by finally formalizing the United States’ northern border with British-ruled Canada.[15] Thus with the help of Ambassador Everett, Webster was able to bring to a conclusion one of the last unresolved measures of the American Revolution—ending a border dispute that had existed since the 1783 Peace of Paris.[16] In so doing, Webster used 19th-century international diplomacy to carve out his own place in American Revolutionary history. Overall, the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections’ Daniel Webster collection provides access to more private aspects of the United States’ diplomatic history and appointments during the 19th-century.

After President William Henry Harrison died one month into his term, Webster held the auspicious title of being the secretary of state under the shortest presidential administration in American history. In addition, he has the even more dubious distinction of turning down the office of vice president under Harrison, who was the first president to die in office, because he viewed it as beneath him.[13] As an ironic conciliatory prize, Webster served as “acting President” for two days until Vice President John Tyler arrived in Washington, D.C., to assume the position from the fallen Harrison.[14] Webster retained his post under Tyler until he resigned in 1843. The culmination of his efforts in the State Department reached its pinnacle with the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which eased decades of hostility with Great Britain by finally formalizing the United States’ northern border with British-ruled Canada.[15] Thus with the help of Ambassador Everett, Webster was able to bring to a conclusion one of the last unresolved measures of the American Revolution—ending a border dispute that had existed since the 1783 Peace of Paris.[16] In so doing, Webster used 19th-century international diplomacy to carve out his own place in American Revolutionary history. Overall, the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections’ Daniel Webster collection provides access to more private aspects of the United States’ diplomatic history and appointments during the 19th-century.

Notes:

Robert V. Remini. Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1997, p. 52.

Robert V. Remini. Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1997, p. 52.- Remini, p. 502.

- Robert Treat Paine to Daniel Webster, 19 Feb. 1841; Henry Wheaton to Daniel Webster, 25 Nov. 1840.

- Enoch Train to Daniel Webster, 8 Feb. 1841; Josiah W. Blake to Daniel Webster, 11 Feb. 1841; Henry Edwards, 24 Mar. 1841; William Bennett Parker to Daniel Webster, 12 Mar. 1841; 13 Mar. 1841; 10 June 1841; 1 Dec. 1841; 23 Apr. 1842; 11 Jul. 1842.

- William Bennett Parker to Daniel Webster, 12 Mar. 1841.

- Kenneth E. Shewmaker, ed. The Papers of Daniel Webster: Diplomatic Papers, Volume 1, 1841-1843. Hanover: Dartmouth College by the University Press of New England, 1983, p. 7.

- Remini, p. 513.

- Shewmaker, p. 7; Remini, p. 513.

- Washington Irving to Daniel Webster. 3 Jul. 1841; Washington Irving to Daniel Webster. 25 Oct. 1841.

- Washington Irving to Daniel Webster. 25 Oct. 1841.

- Robert C. Winthrop to Daniel Webster, 24 Mar. 1841.

- Shewmaker, p. 7; Remini, p. 520.

- Remini, p. 480.

- Remini, p. 522.

- “The Webster-Ashburton Treaty,” in Howard Jones, To the Webster-Ashburton Treaty: A Study in Anglo-American Relations, 1783-1843. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

- Jones, p. 118-160.