Dante's Divine Comedy, Censored by Spanish Inquisition

August 30, 2010

Description and translations by Aaron Wirth, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in the Comparative History Program

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis houses a number of rare works by Dante Alighieri, such as the Aldine Press' first edition of "Le terze rime di Dante" (1502), Henry Longfellow’s translation of the "Divine Comedy" (1867), and Dante col sito, et forma dell'inferno tratta dalla istessa descrittione del poeta (1515). A 1564 edition of "La Divina Comedia" from Arévalo, Spain, however, is particularly noteworthy for several reasons.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis houses a number of rare works by Dante Alighieri, such as the Aldine Press' first edition of "Le terze rime di Dante" (1502), Henry Longfellow’s translation of the "Divine Comedy" (1867), and Dante col sito, et forma dell'inferno tratta dalla istessa descrittione del poeta (1515). A 1564 edition of "La Divina Comedia" from Arévalo, Spain, however, is particularly noteworthy for several reasons.

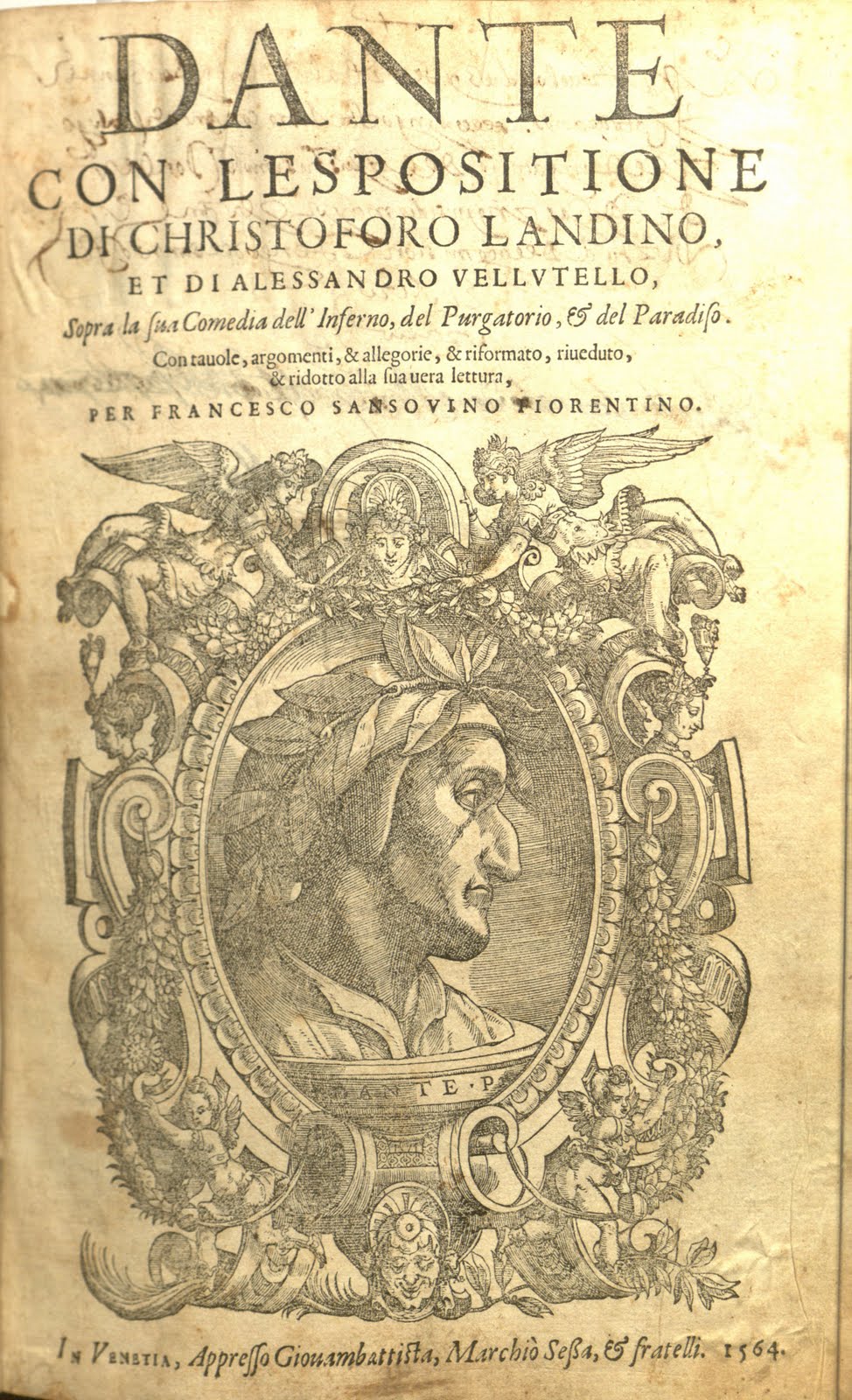

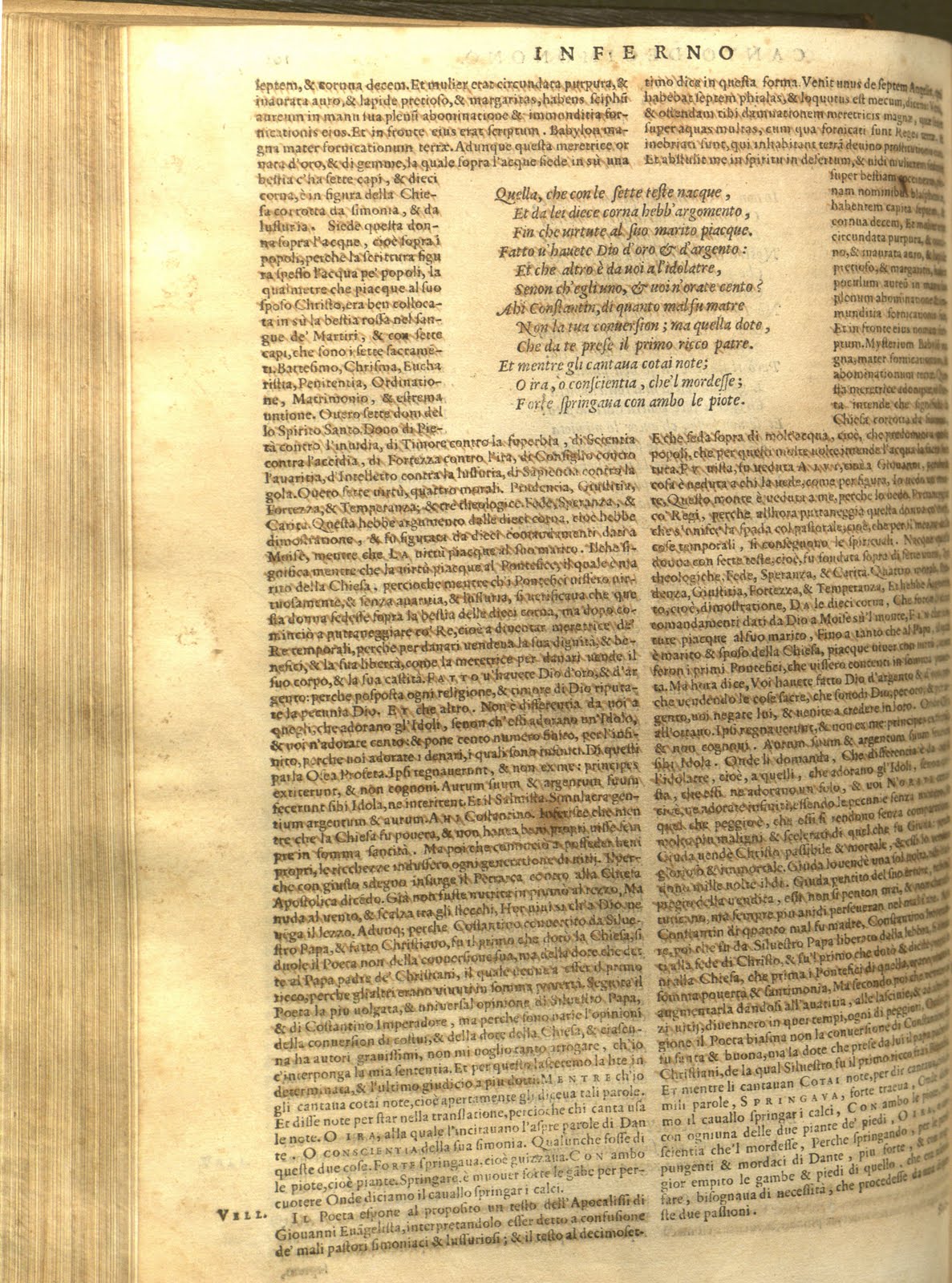

In the 1564 edition held by Brandeis, the poem is encircled by commentaries from Christoforo Landino, Allesandro Vellutelloand Francesco Sansovino, all of whom were well-known Dante critics of their respective times. A consideration of the historical context of the poem and its criticisms is also interesting, in light of Spain's treatment of Dante and other libri vulgari during the 15th and 16th centuries. Last, and perhaps most fascinating of all, specific passages of the critics’s commentaries, along with verses of the poem, were expurgated by a Spanish Inquisition cleric. Fortunately for the reader, the cleric's ink faded over the years, allowing one to read the poem's redacted portions.

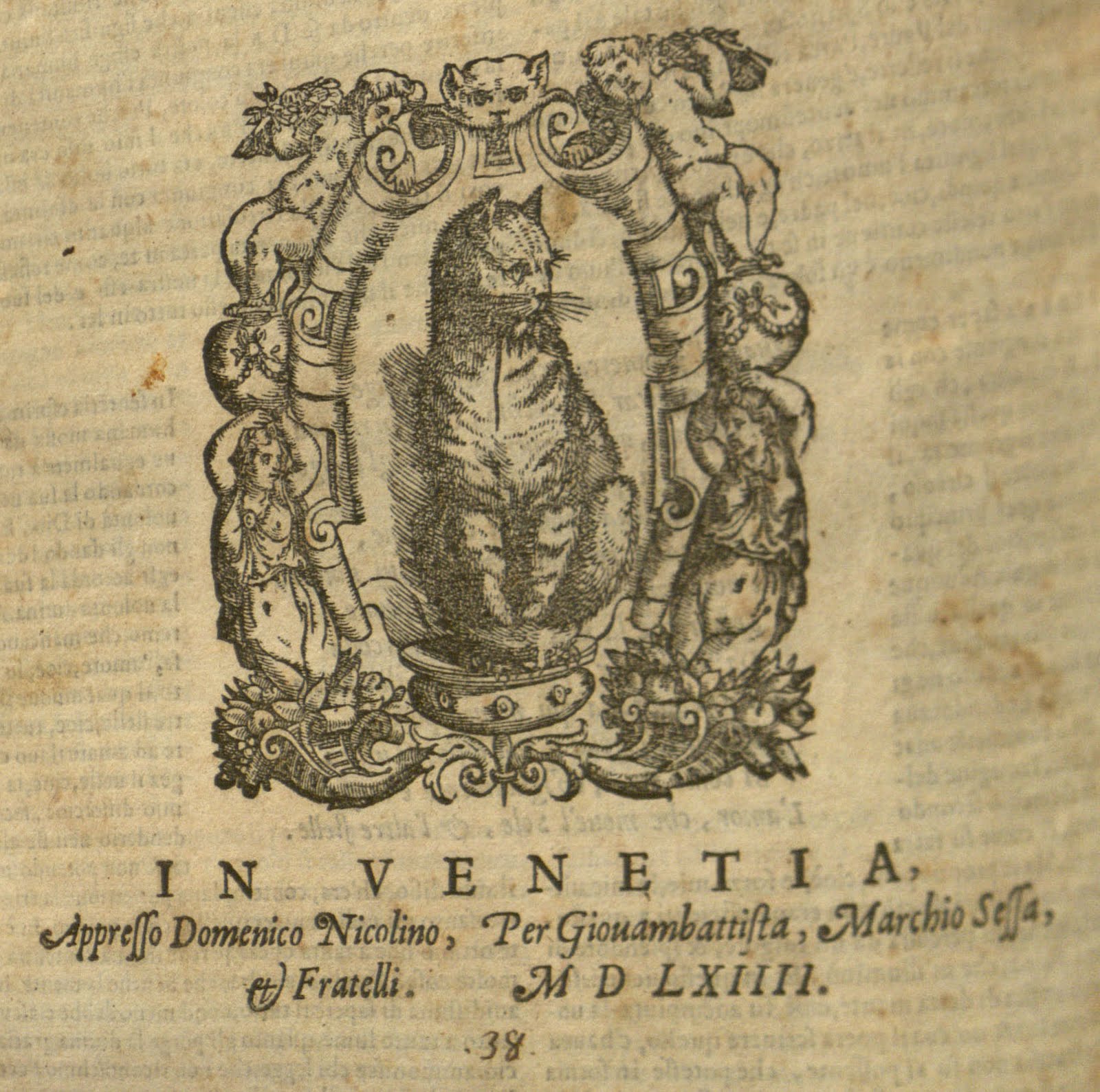

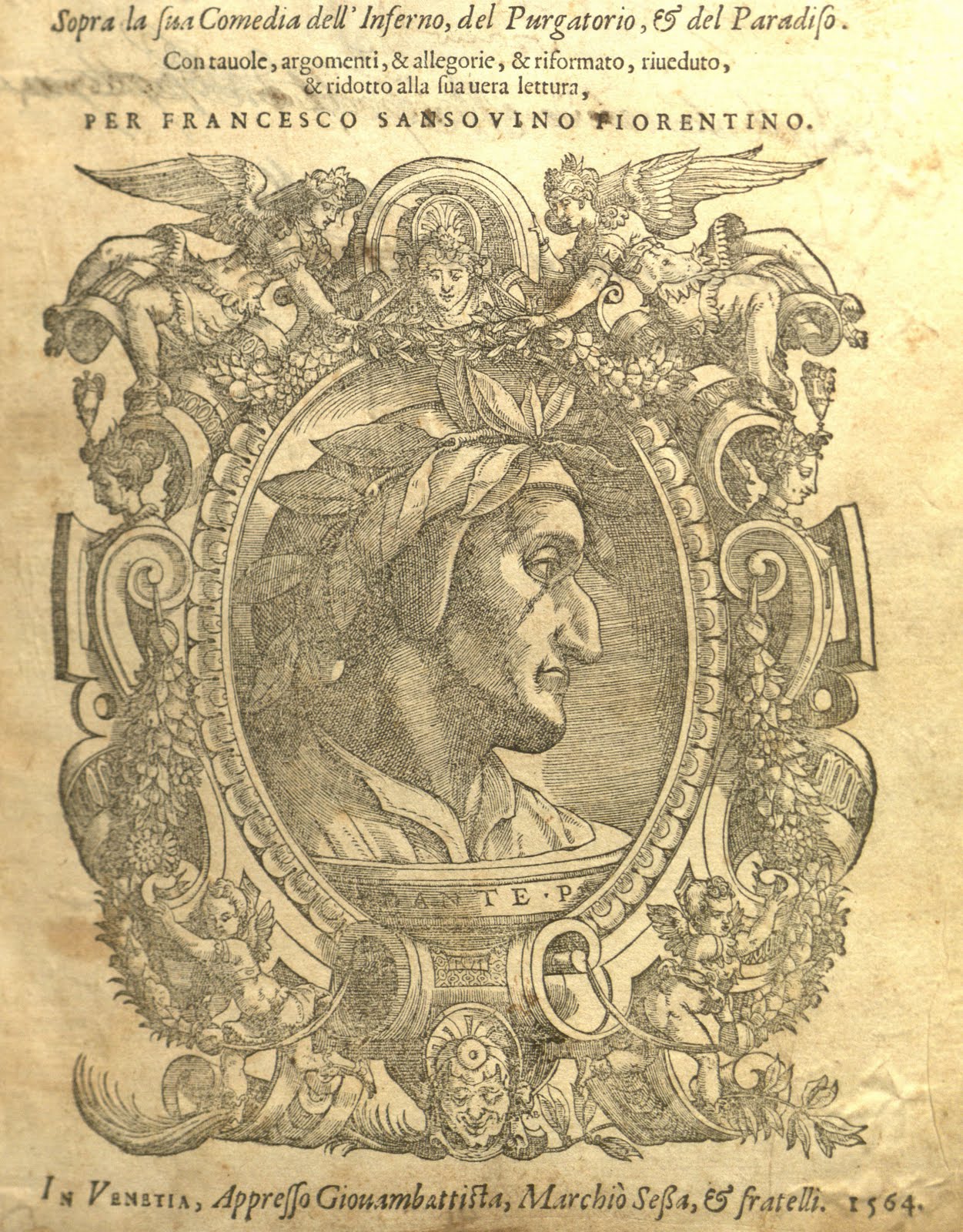

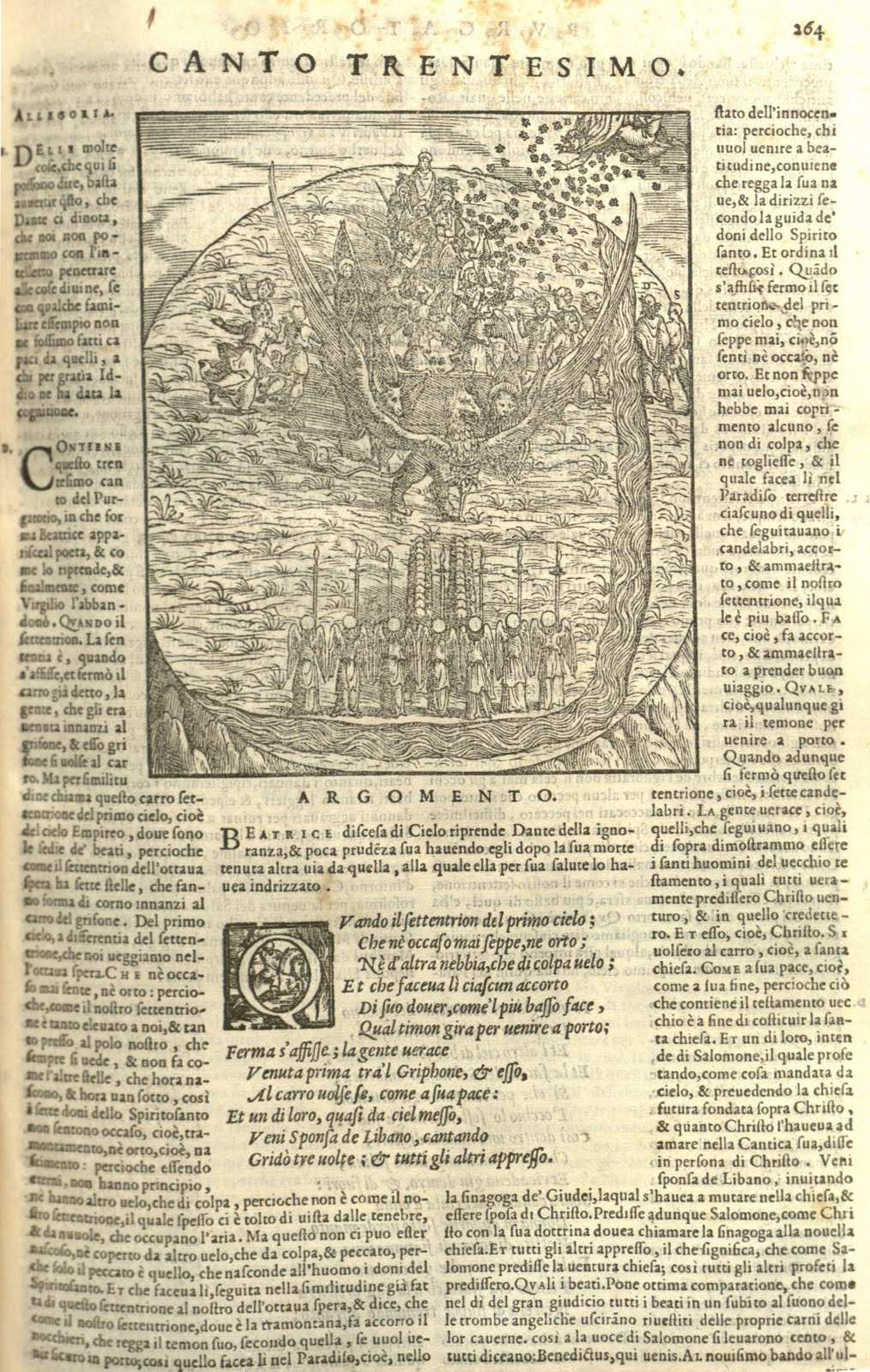

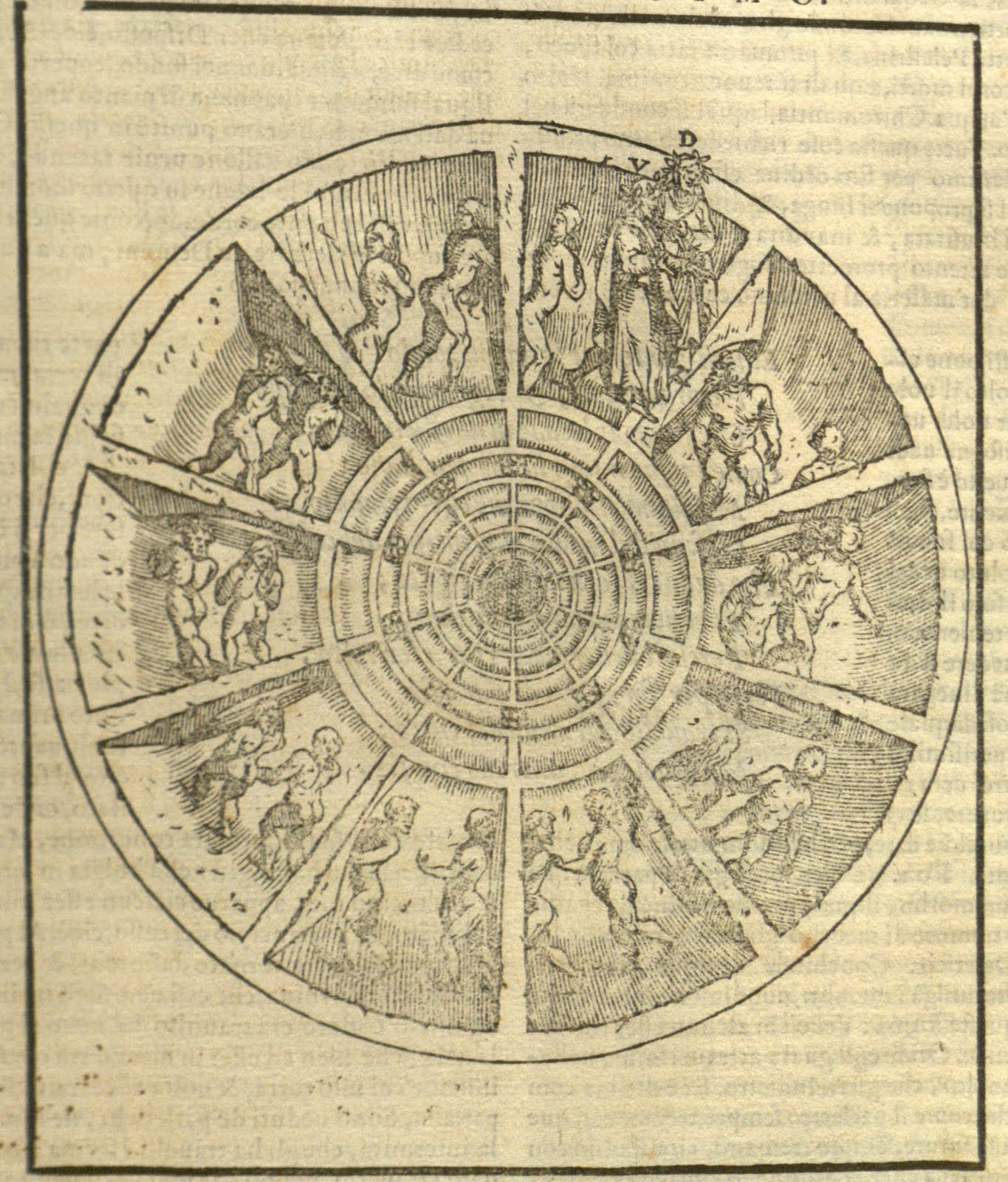

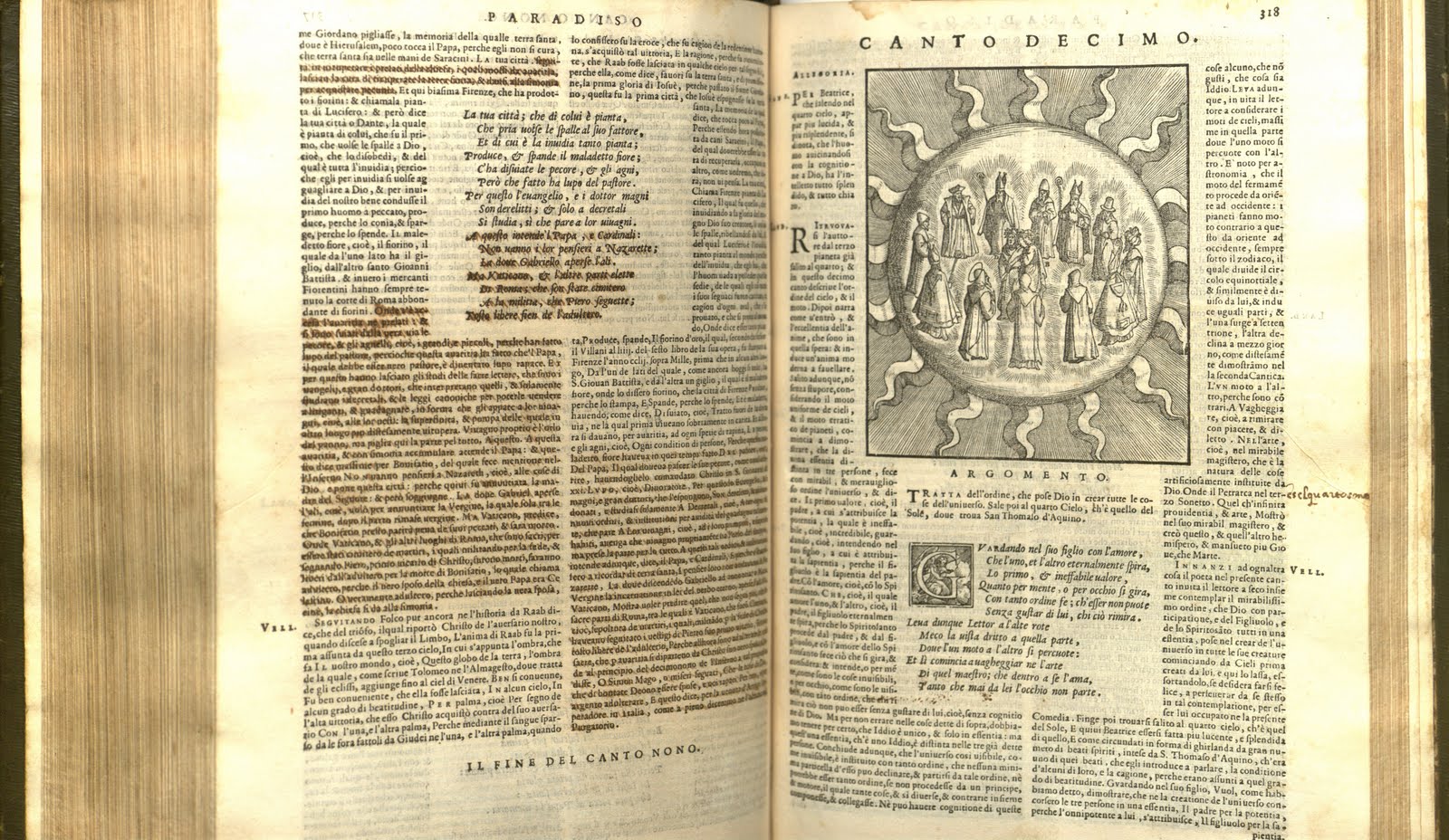

This edition of the "Divine Comedy" is the first of three published by the Sessa family of Venetian printers. The title page is adorned with a portrait by Giorgio Vasari of Dante caricatured with an enlarged nose (because of the exaggerated nose, this edition in Italy is referred to as the Edizioni del gran naso), and the last page contains the Sessa family's printer mark: a cat, seated on a pillow with a mouse in its mouth. Throughout the book, scenes from the "Divine Comedy" are shown in beautiful woodcuts.

This edition of the "Divine Comedy" is the first of three published by the Sessa family of Venetian printers. The title page is adorned with a portrait by Giorgio Vasari of Dante caricatured with an enlarged nose (because of the exaggerated nose, this edition in Italy is referred to as the Edizioni del gran naso), and the last page contains the Sessa family's printer mark: a cat, seated on a pillow with a mouse in its mouth. Throughout the book, scenes from the "Divine Comedy" are shown in beautiful woodcuts.

Editor Francesco Sansovino (1521-83) beautifully combined his own commentaries with those of two other well-known critics, Alessandro Vellutello (1473-?) and Cristoforo Landino (1424-98) in one book, to create an innovative hybrid. Sansovino, a versatile Roman publisher and man of letters, often wrote on Boccaccio, Dante and the city of Venice. The Florentine humanist Landino was a prolific writer and chair of Poetry and Rhetoric at Florentine's Studio who advocated the use of vernacular Italian, wrote commentaries on the "Aeneid" and lectured on Petrarch. Vellutello, a Lucchese academic active in Venice during the early 1500s, not only wrote on Dante but also was a Petrarch enthusiast.

Editor Francesco Sansovino (1521-83) beautifully combined his own commentaries with those of two other well-known critics, Alessandro Vellutello (1473-?) and Cristoforo Landino (1424-98) in one book, to create an innovative hybrid. Sansovino, a versatile Roman publisher and man of letters, often wrote on Boccaccio, Dante and the city of Venice. The Florentine humanist Landino was a prolific writer and chair of Poetry and Rhetoric at Florentine's Studio who advocated the use of vernacular Italian, wrote commentaries on the "Aeneid" and lectured on Petrarch. Vellutello, a Lucchese academic active in Venice during the early 1500s, not only wrote on Dante but also was a Petrarch enthusiast.

The commentaries by these three renowned writers are an excellent find for early modern historians, Italian linguists or dantisti. Comparatively, the commentaries suffered a great deal more redaction than the poem. Specifically, the commentaries of Landino and Vellutello, and a few verses of the "Inferno" and "Paradiso," were condemned. Why the cleric chose to completely ignore Sansovino's commentary is unknown, yet one particular variable may shed light on the matter: the Florentine editor dedicated his edition of the poem to Pope Pius IV.

The commentaries by these three renowned writers are an excellent find for early modern historians, Italian linguists or dantisti. Comparatively, the commentaries suffered a great deal more redaction than the poem. Specifically, the commentaries of Landino and Vellutello, and a few verses of the "Inferno" and "Paradiso," were condemned. Why the cleric chose to completely ignore Sansovino's commentary is unknown, yet one particular variable may shed light on the matter: the Florentine editor dedicated his edition of the poem to Pope Pius IV.

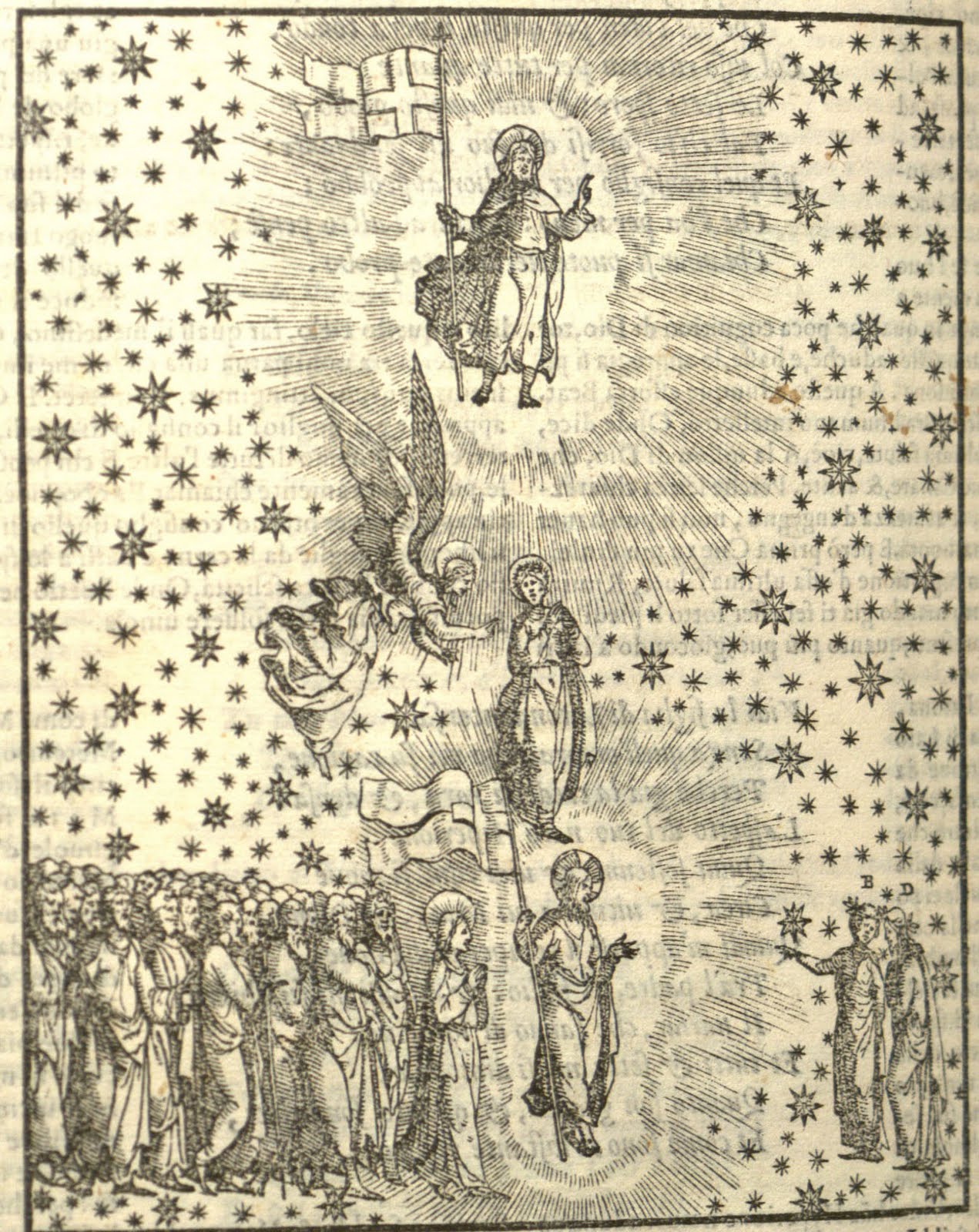

The "Divine Comedy" is written in the first person and tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead — Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory) and Paradiso (Paradise) — with his guides: the Roman poet Virgil, and, subsequently, Dante's courtly love, Beatrice. Hell is described as an inverted cone with the point being Lucifer's land at the center of the world. The pilgrimage from Hell is a climb to the foot of, and then up to the top of, the Mountain of Purgatory. Along the way Dante passes warriors, kings and emperors, fellow poets, popes and citizens of Florence, amending the sins of their life on Earth. On the summit is the Earthly Paradise, where the two meet Beatrice, and Virgil subsequently departs. Dante is led through the various spheres of heaven, and the poem ends with a vision of the deity.

The "Divine Comedy" is written in the first person and tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead — Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory) and Paradiso (Paradise) — with his guides: the Roman poet Virgil, and, subsequently, Dante's courtly love, Beatrice. Hell is described as an inverted cone with the point being Lucifer's land at the center of the world. The pilgrimage from Hell is a climb to the foot of, and then up to the top of, the Mountain of Purgatory. Along the way Dante passes warriors, kings and emperors, fellow poets, popes and citizens of Florence, amending the sins of their life on Earth. On the summit is the Earthly Paradise, where the two meet Beatrice, and Virgil subsequently departs. Dante is led through the various spheres of heaven, and the poem ends with a vision of the deity.

While the reader accompanies Dante on his journey, it quickly becomes apparent that the number 3 — the Trinity — is prominent in the work. The author's entire journey lasts from the evening of Maundy Thursday to the Wednesday after Easter of 1300. The poem is composed of over 14,000 lines divided into three cantiche (canticas), which make up the deceased’s realms: Hell, Purgatory and Paradise each consisting of 33 canti (cantos). The Poet uses the scheme terza rima, a hendecasyllabic (lines of 11 syllables), with the lines composing tercets based on the rhyming scheme aba, bcb, cdc, ded…

While the reader accompanies Dante on his journey, it quickly becomes apparent that the number 3 — the Trinity — is prominent in the work. The author's entire journey lasts from the evening of Maundy Thursday to the Wednesday after Easter of 1300. The poem is composed of over 14,000 lines divided into three cantiche (canticas), which make up the deceased’s realms: Hell, Purgatory and Paradise each consisting of 33 canti (cantos). The Poet uses the scheme terza rima, a hendecasyllabic (lines of 11 syllables), with the lines composing tercets based on the rhyming scheme aba, bcb, cdc, ded…

The poem recognizes several historical incidents and people, but the primary influence is the Florentine politics of Dante's time. During central Italy's political struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines, Dante sided with the Guelphs, who favored the papacy over the Holy Roman Emperor. At the beginning of the 14th century, Florence's Guelphs divided into the White Guelphs and the Black Guelphs. Dante supported the Whites, who were exiled in 1302 after troops under Charles of Valois entered the city at the request of Pope Boniface VIII, who supported the Blacks. The exile lasted the rest of Dante's life, and its influence on the Divine Comedy is evident in his views of politics on the peninsula and prophecies of his exile and of the eternal damnation of some of his opponents; some of these views and criticisms of the church were seen as heretical by the Spanish Inquisitors.

The Spanish Inquisition was the tribunal court system used by both the Catholic Church and Spanish Catholic monarchs. Founded in 1478 by Ferdinand II and Isabella to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms, the Inquisition was under the direct control of the Spanish monarchy. The Spanish Church worked actively to curb the spread of heretical ideas in Spain by using the Catholic Church's Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Forbidden Books) over the course of several years. The Index's purpose was to stop the contamination of the faith or the corruption of beliefs and morals of Roman Catholics according to canon law through the reading of immoral or theologically erroneous texts. The Index included books of all genres, yet particular attention was dedicated to religious works, specifically vernacular translations of the Bible.

At the outset, inclusion in the Index meant complete censure of a text; however, this proved not only impractical, but contrary to the goal of maintaining a well-educated, literate clergy. In time, a compromise was agreed upon in which trained Inquisition officials inked out words, or entire passages, of unacceptable texts, allowing the expurgated editions to circulate. The readings, including the "Divine Comedy," were regarded as books that no good Catholic might read until they had been redacted by the Holy Office.

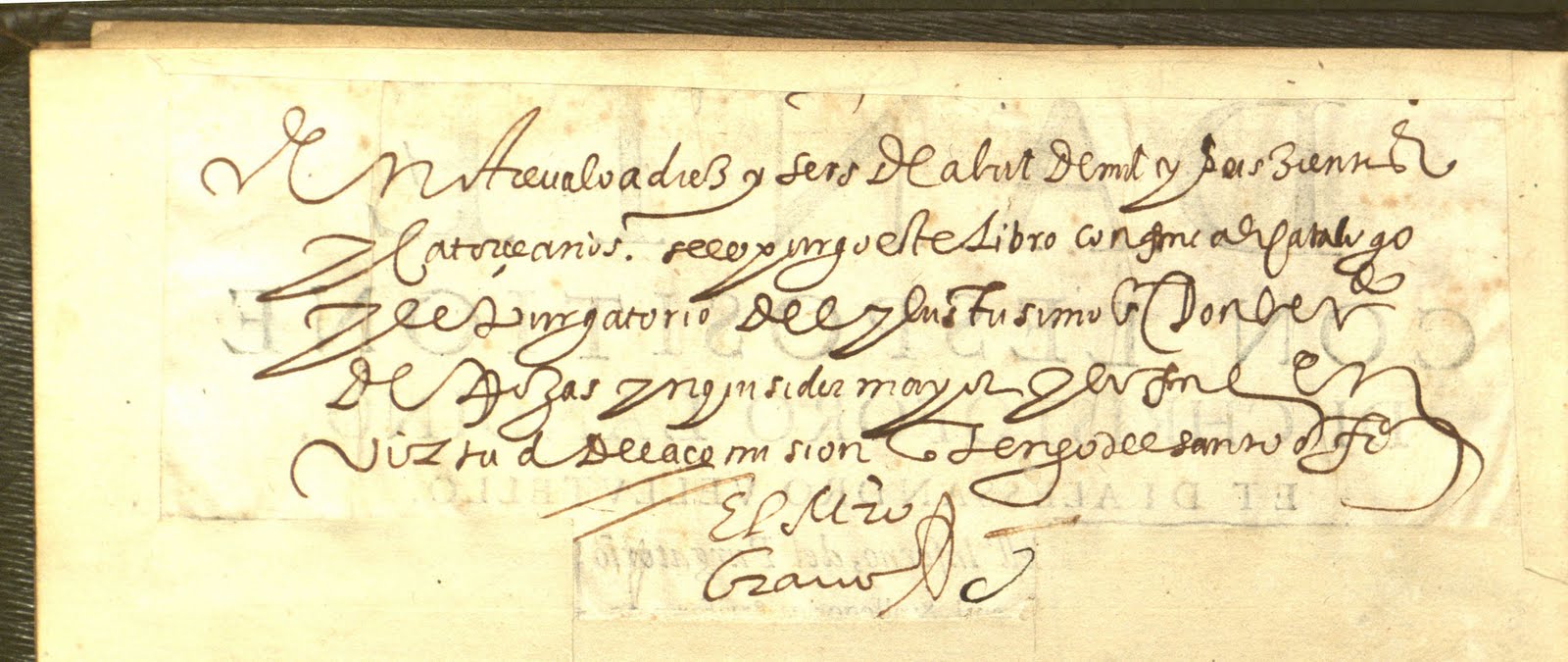

At the outset, inclusion in the Index meant complete censure of a text; however, this proved not only impractical, but contrary to the goal of maintaining a well-educated, literate clergy. In time, a compromise was agreed upon in which trained Inquisition officials inked out words, or entire passages, of unacceptable texts, allowing the expurgated editions to circulate. The readings, including the "Divine Comedy," were regarded as books that no good Catholic might read until they had been redacted by the Holy Office.  A cleric would expurgate those passages of text deemed offensive. Fortunately, the 1564 copy of the "Divine Comedy" at Brandeis contains an original document pasted on the back of the title page, signed by one of the Inquisitors, that states that the necessary cancellations have been made in this copy. The message, in Spanish, reads: "Arévalo, Spain, on April 16, 1614, this book has been purged in accordance with the Expurgatory Catalogue of Don Fernando de Riezas, Head Inquisitor; so empowered by the Commission of the Holy Office…" The redacted passages can easily be found upon examination of the book; the ink used in the cancellation has essentially faded out, and the printed words underneath have reappeared, enabling one to read the entirety of the incriminated passages without difficulty.

A cleric would expurgate those passages of text deemed offensive. Fortunately, the 1564 copy of the "Divine Comedy" at Brandeis contains an original document pasted on the back of the title page, signed by one of the Inquisitors, that states that the necessary cancellations have been made in this copy. The message, in Spanish, reads: "Arévalo, Spain, on April 16, 1614, this book has been purged in accordance with the Expurgatory Catalogue of Don Fernando de Riezas, Head Inquisitor; so empowered by the Commission of the Holy Office…" The redacted passages can easily be found upon examination of the book; the ink used in the cancellation has essentially faded out, and the printed words underneath have reappeared, enabling one to read the entirety of the incriminated passages without difficulty.

The "Divine Comedy" is best described as an allegory: that is, each canto can contain many alternative meanings. Dante's allegory is complex and multilayered, showing the moral, the historical, the anagogical, the political and the literal. Below are the three excerpts from the poem that were once hidden, but are now visible again, coupled with commentaries that may help the reader understand what exactly the intentions were of the Supreme Poet.

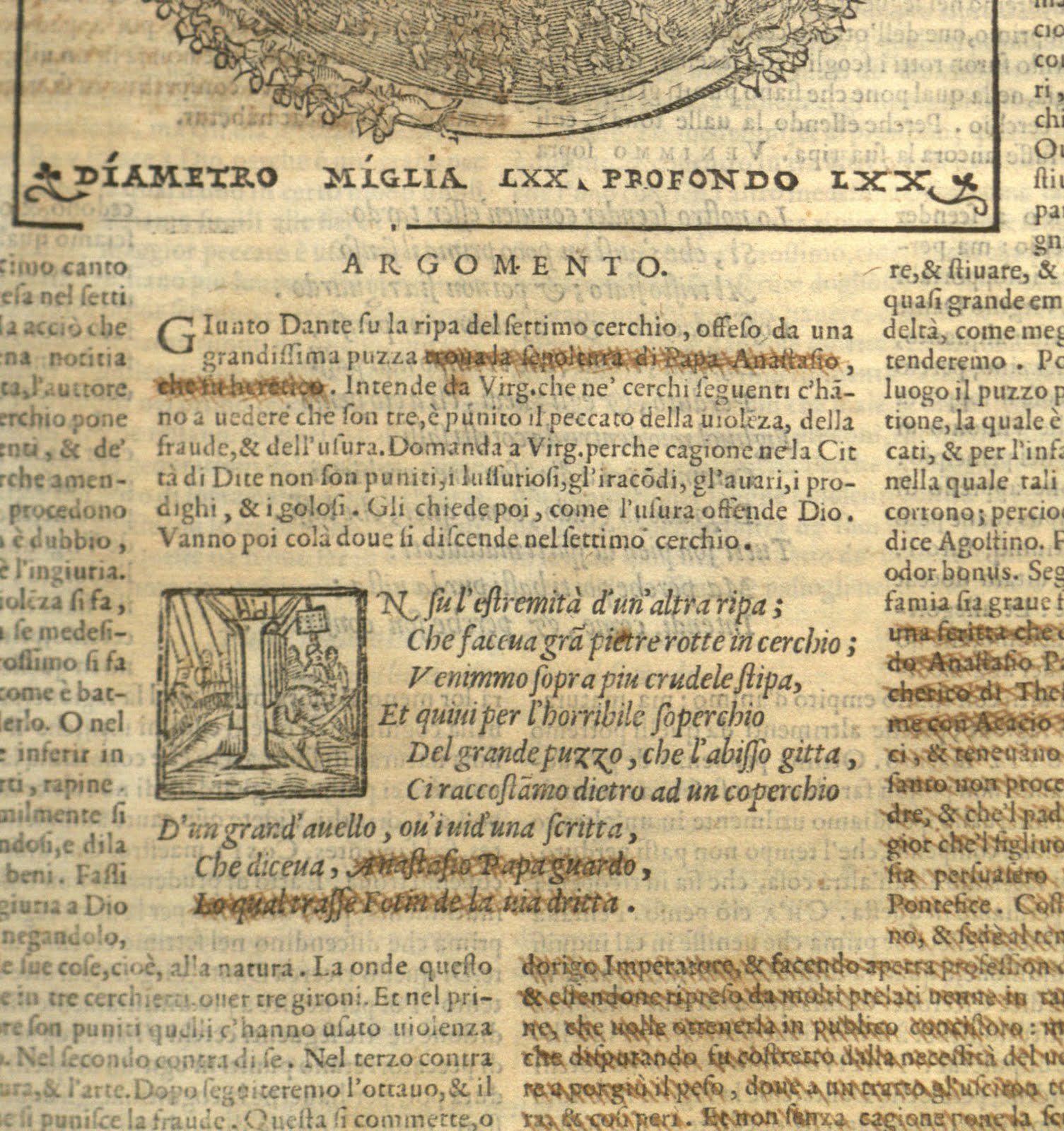

Inferno Canto XI 7–9

d'un grand’'avello, ov'io vidi una scritta

che dicea: “Anastasio papa guardo,

lo qual trasse Fotin de la vita dritta.”

On a great tomb, I saw that it was inscribed:

“Pope Anastasius I contain, the Pope

Photinus lured away from the correct path.”

A rather amusing medieval tradition has confused Anastasius II, pope from 496-498, and his namesake and contemporary Anastasius I, emperor from 491-518. For many centuries, Anastasius II was widely believed to be a heretic because he supposedly allowed Photinus, a deacon of Thessalonica who followed the heresy of Acacius (Byzantine Emperor, patriarch of Constantinople), to take communion. Acacius denied the divine origin of Christ, holding that Christ was naturally begotten and conceived in the same way as mankind. Dante was simply following the accepted tradition of the time concerning Pope Anastasius’ heretical persuasion.

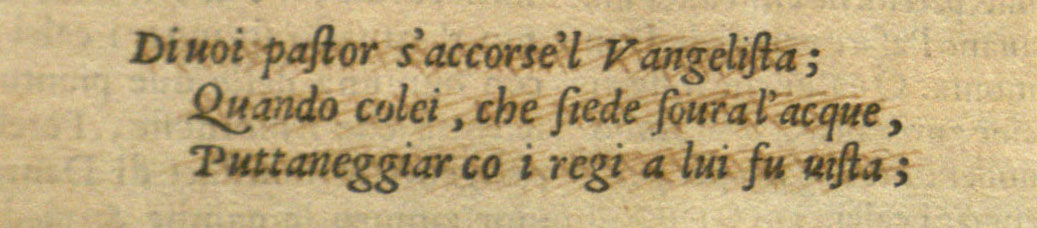

Inferno Canto XIX 106–117

Di voi pastor s'accorse'l Vangelista;

Di voi pastor s'accorse'l Vangelista;

quando colei che siede soura l’acque

puttaneggiar co i regi a lui fu vista;

quella, che con le sette teste nacque,

et da la diece corna hebb'argomento,

fin che virtute al suo marito piacque. Fatto v'havete dio d'oro e d'argento;

Fatto v'havete dio d'oro e d'argento;

et che altro è da voi a l'idolatre,

senon ch'egli uno, e voi n'orate centro?

Ahi, Constantin, di quanto mal fu matre,

non la tua conversion, ma quella dote

che da te prese il primo ricco patre!

You shepherds the Evangelist envisioned

when he was witness to She who sits

on the waters playing whore with kings:

She the one who was born with seven heads

and from her ten horns that could draw strength

as long as virtue and love pleased her spouse.

Gold and silver are gods you praise!

how do you differ from the idolator,

only he worships one, you all a score?

Oh, Constantine, what evil marked the hour,

not by your conversion, but of that fee

the first wealthy Father took from you in gift!

In this excerpt, John the Evangelist describes his vision of corrupt Rome. To Dante, the one who "sits upon the waters" represents the Vatican, which has been corrupted by the simoniacal activities of previous popes, or the "shepherds" of the church. The seven heads represent the seven sacraments, while the 10 horns represent the 10 commandments that allowed the Church its strength as long as the pope "suo marito" ruled justly. The verb puttaneggiare is reminiscent of the verb simoneggiare, which appears in Nicholas' speech and was actually invented by Dante. The linguistic link shows the reader evidence of the creative relationship between simony and prostitution. In fact, simony was defined as a type of prostitution of the Church motivated by greed. The significance of this verse is debatable and could be viewed as "For every idol they worship, you worship a hundred." More likely, however, is that this verse contains a reference to the golden calf of the Israelites and therefore could be construed to mean "You worship not just one idol, but everything that is of gold." According to a legend universally accepted in the Middle Ages as historical fact, Constantine the Great (Roman Emperor 306-336), before he removed his government to Byzantium in 330, abandoned to the Church his temporal power in the West.

The linguistic link shows the reader evidence of the creative relationship between simony and prostitution. In fact, simony was defined as a type of prostitution of the Church motivated by greed. The significance of this verse is debatable and could be viewed as "For every idol they worship, you worship a hundred." More likely, however, is that this verse contains a reference to the golden calf of the Israelites and therefore could be construed to mean "You worship not just one idol, but everything that is of gold." According to a legend universally accepted in the Middle Ages as historical fact, Constantine the Great (Roman Emperor 306-336), before he removed his government to Byzantium in 330, abandoned to the Church his temporal power in the West.

The move, according to a document known as the Donation of Constantine, stemmed from Constantine's decision to place the western part of the empire under the jurisdiction of the Church to repay Pope Sylvester for healing him of leprosy. The Donation of Constantine was proved to be a forgery by Lorenzo Valla in the 15th century, yet was accepted as truth in the Middle Ages. Dante did not doubt the authenticity of a document so widely accepted as genuine in his day, but he did deny that it had any juridical value. The author reflects this tradition in his statement to Constantine, the man who would ultimately be responsible for the present corruption of the Church.

Paradiso Canto IX 136–142

A questo intende'l papa e'cardinali;

A questo intende'l papa e'cardinali;

non vanno I lor pensieri a Nazarette,

là dove Gabrïello aperse l'ali.

Ma Vaticano e l'altre parti elette

di Roma che son state cimitero

a la milizia che Pietro seguette,

tosto libere fien de l’adultero.

So Pope and Cardinals mind no other things;

their thoughts do not go out to Nazareth

where Gabriel once opened his wings wide.

But the Vatican and other chosen parts,

of Rome that you all have been, from the first,

the cemetery of those faithful men

that followed Peter and were his soldiers,

shall soon be free of this adultery.

Nazareth is the scene of the Annunciation, where Gabriel "opened his wings" before Mary. The Vatican hill in Rome is the location of both St. Peter's basilica and the Vatican palace. The papal residence, during Dante's life, was the Lateran Palace. The Vatican has been the usual residence of the popes since their return from Avignon in the latter half of the 14th century. Additionally, the Vatican hill, the location of Peter's and other early Christians' martyrdom, is considered to be the most sacred area in Rome. The meaning of these closing verses is widely disputed, and they may refer to the removal of the Papal Court to Avignon in 1305, or perhaps to the death of Boniface VIII. More obvious, however, are the final lines. The influence of money, greed and corruption from Florence produced corruption that stretched all the way to the Vatican. Thus, evangelical purpose died with the martyrs. Once again the reader sees a greedy Church government perpetuated by corrupt pontiffs, and the prostitution of things holy for personal gain.

The 1564 Brandeis copy of Dante’s "Divine Comedy" thus acquires a very special interest and importance, particularly as a document of Inquisitorial censure. This edition was made the object of severe excises, many more of which can be found in the commentaries.