Diary (1859-1886) of William Ayrton

April 1, 2014

Description by Surella Evanor Seelig, Archives and Special Collections Coordinator

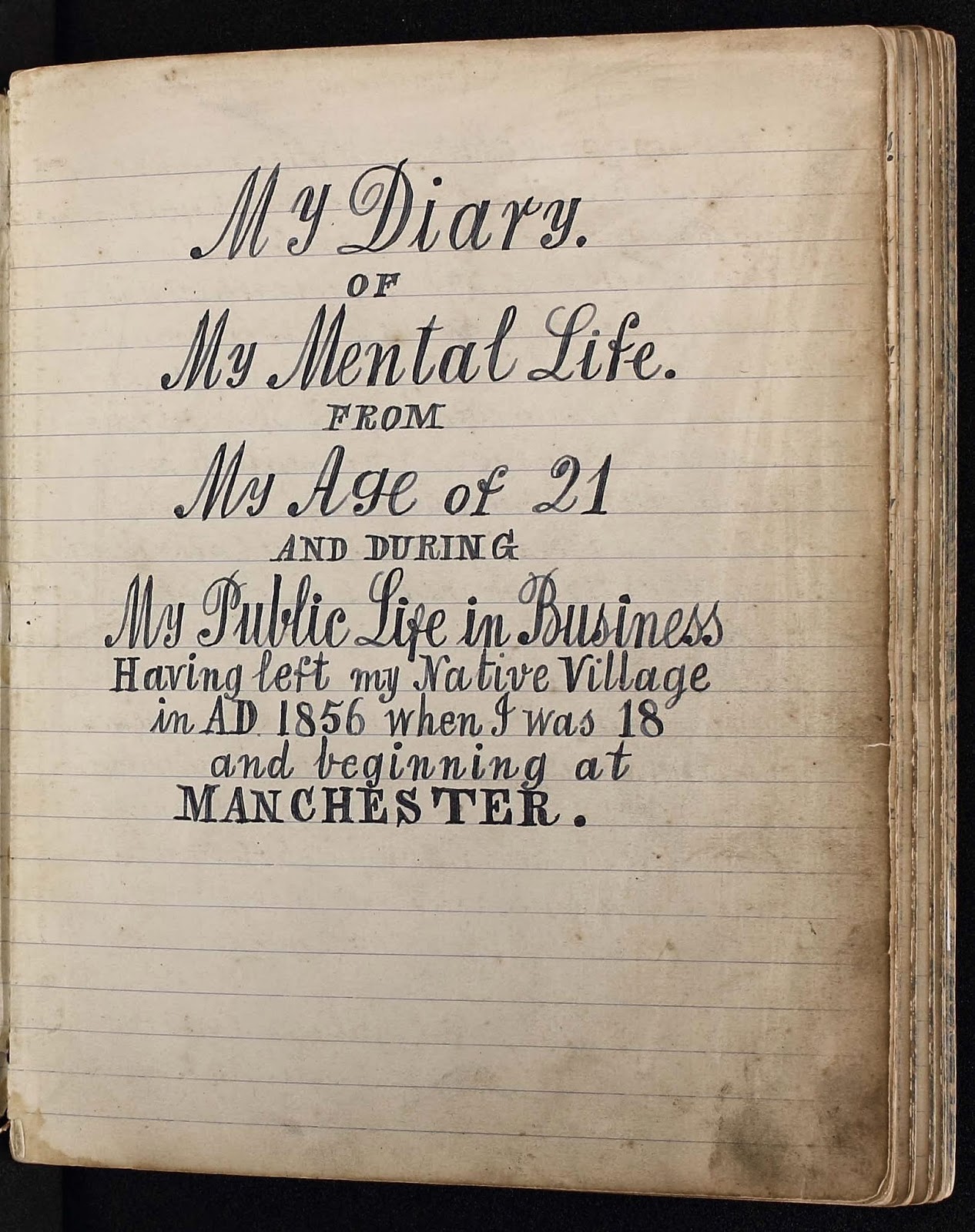

Special Collections is pleased to showcase an exciting recent acquisition: “The Diary of William Ayrton, or: My Diary of My Mental Life from My Age of 21 and during My Public Life in Business Having left my Native Village in AD 1856 when I was 18 and beginning at Manchester.” The entries in this stunningly handwritten notebook tell the story of a young man finding his way in life and grappling with the contradictions between his faith and the modern world he sees around him. In 100 pages, Ayrton transcribes his inner monologue from the age of 21, when he is just starting out in business, to 44, by which point he is an ordained deacon with a wife and children.

Special Collections is pleased to showcase an exciting recent acquisition: “The Diary of William Ayrton, or: My Diary of My Mental Life from My Age of 21 and during My Public Life in Business Having left my Native Village in AD 1856 when I was 18 and beginning at Manchester.” The entries in this stunningly handwritten notebook tell the story of a young man finding his way in life and grappling with the contradictions between his faith and the modern world he sees around him. In 100 pages, Ayrton transcribes his inner monologue from the age of 21, when he is just starting out in business, to 44, by which point he is an ordained deacon with a wife and children.

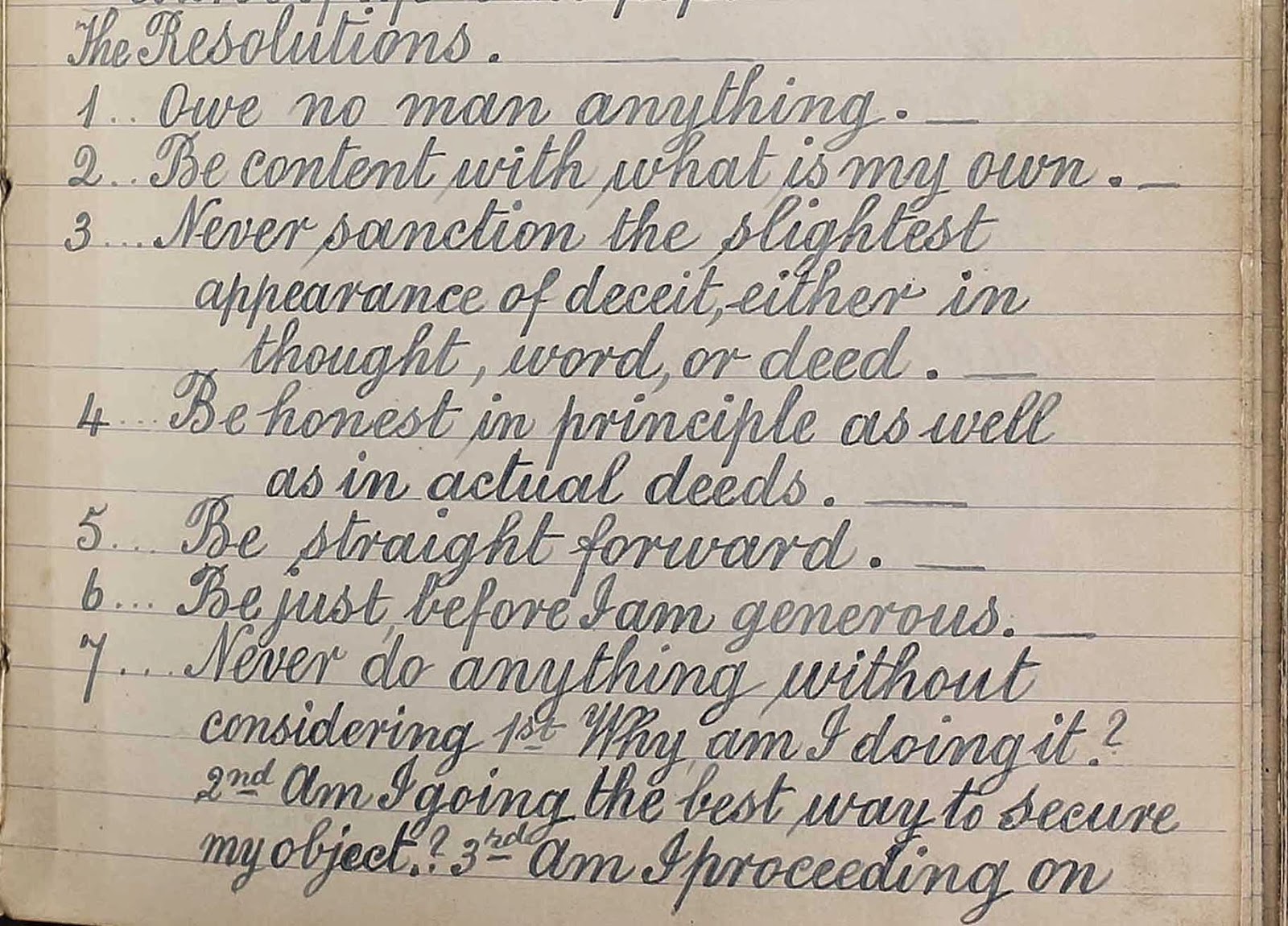

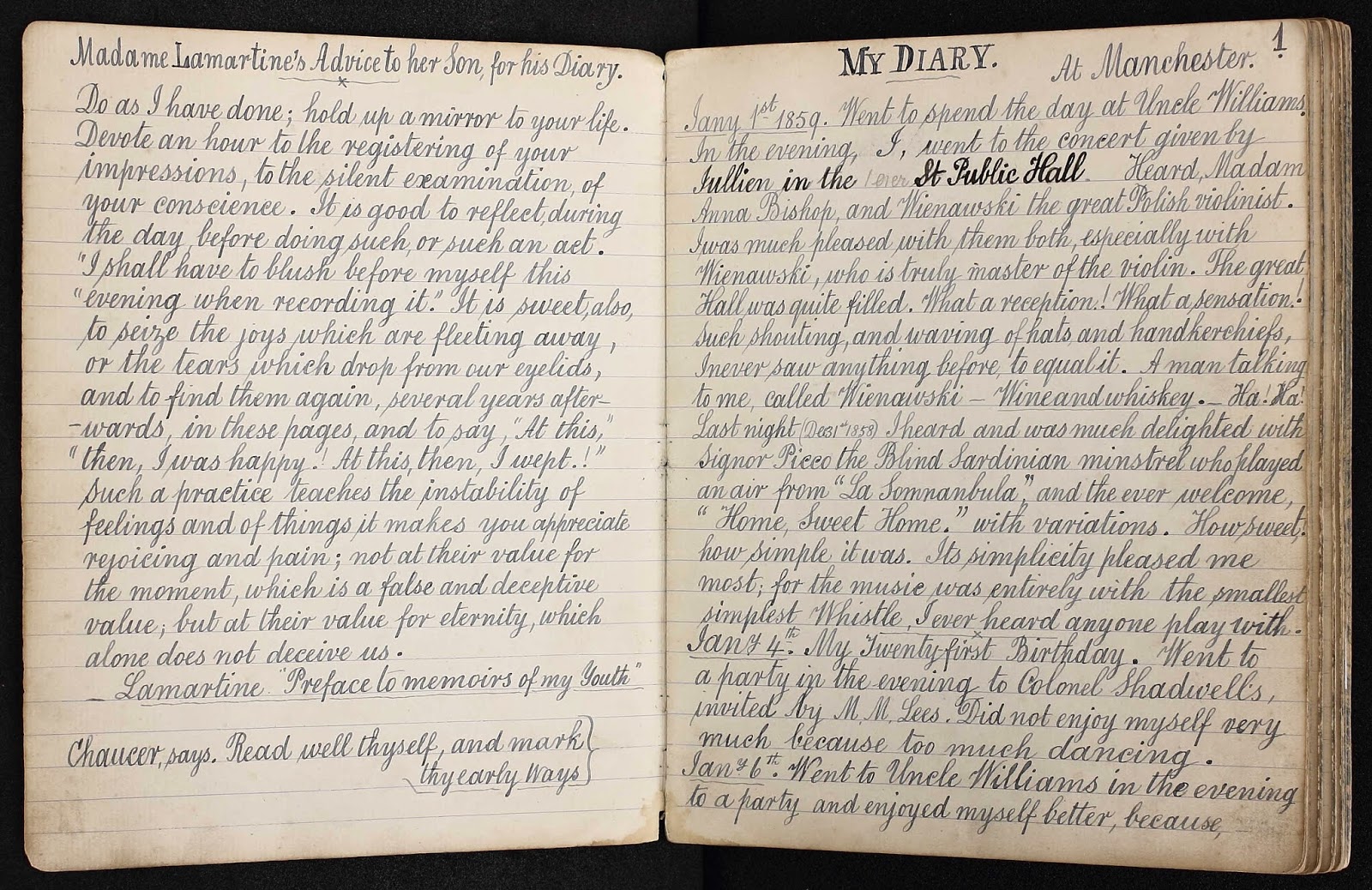

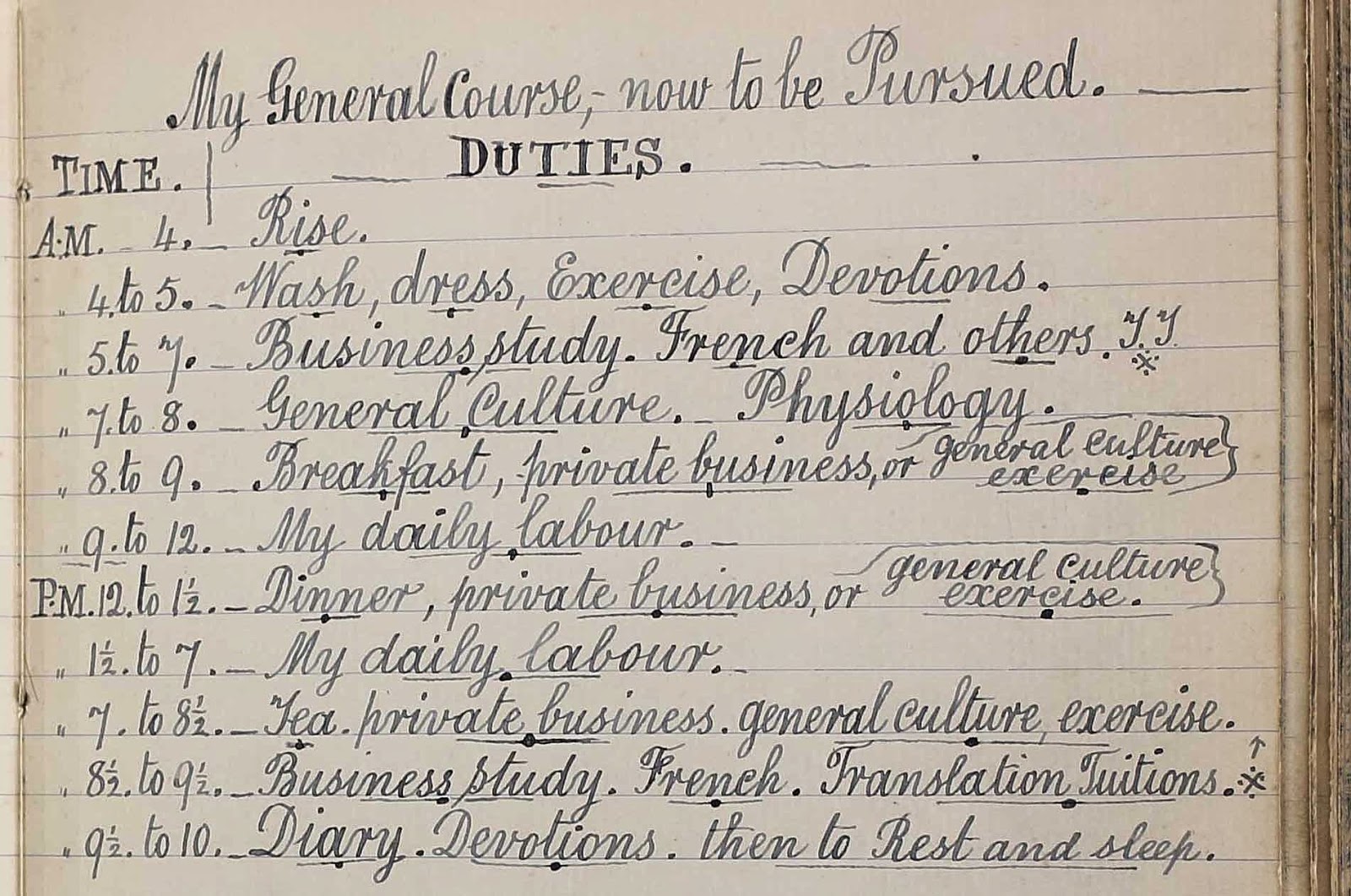

Much of the diary focuses on Ayrton’s relationship with God, and with his struggles to succeed at his work while maintaining a life that adheres to a strict moral and religious code. As the diary opens, the year has just turned 1859, and Ayrton is celebrating his birthday. He outlines what makes a good party and tells of his frustration with having already broken his New Year’s resolutions. We read as Ayrton finds his footing as a clerk and travels for business all over England, and, at one point, to France.

Much of the diary focuses on Ayrton’s relationship with God, and with his struggles to succeed at his work while maintaining a life that adheres to a strict moral and religious code. As the diary opens, the year has just turned 1859, and Ayrton is celebrating his birthday. He outlines what makes a good party and tells of his frustration with having already broken his New Year’s resolutions. We read as Ayrton finds his footing as a clerk and travels for business all over England, and, at one point, to France.

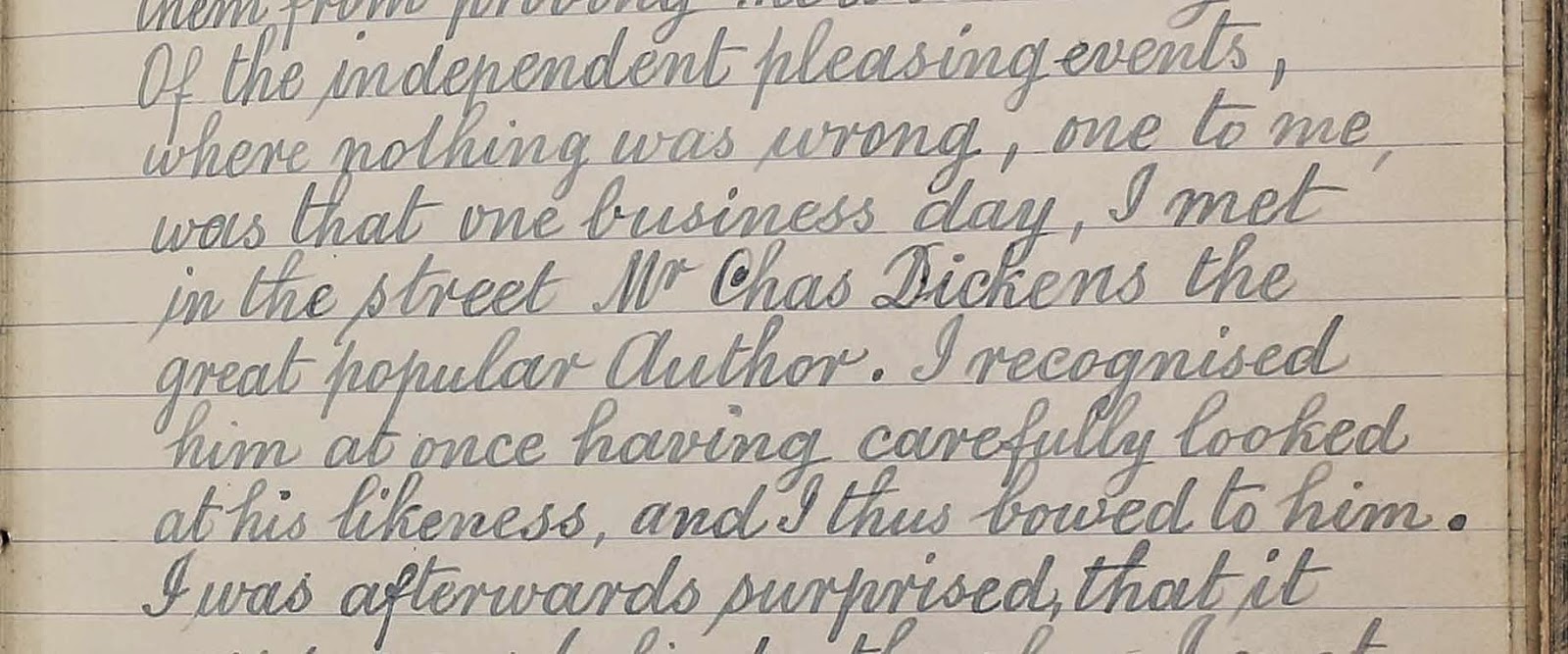

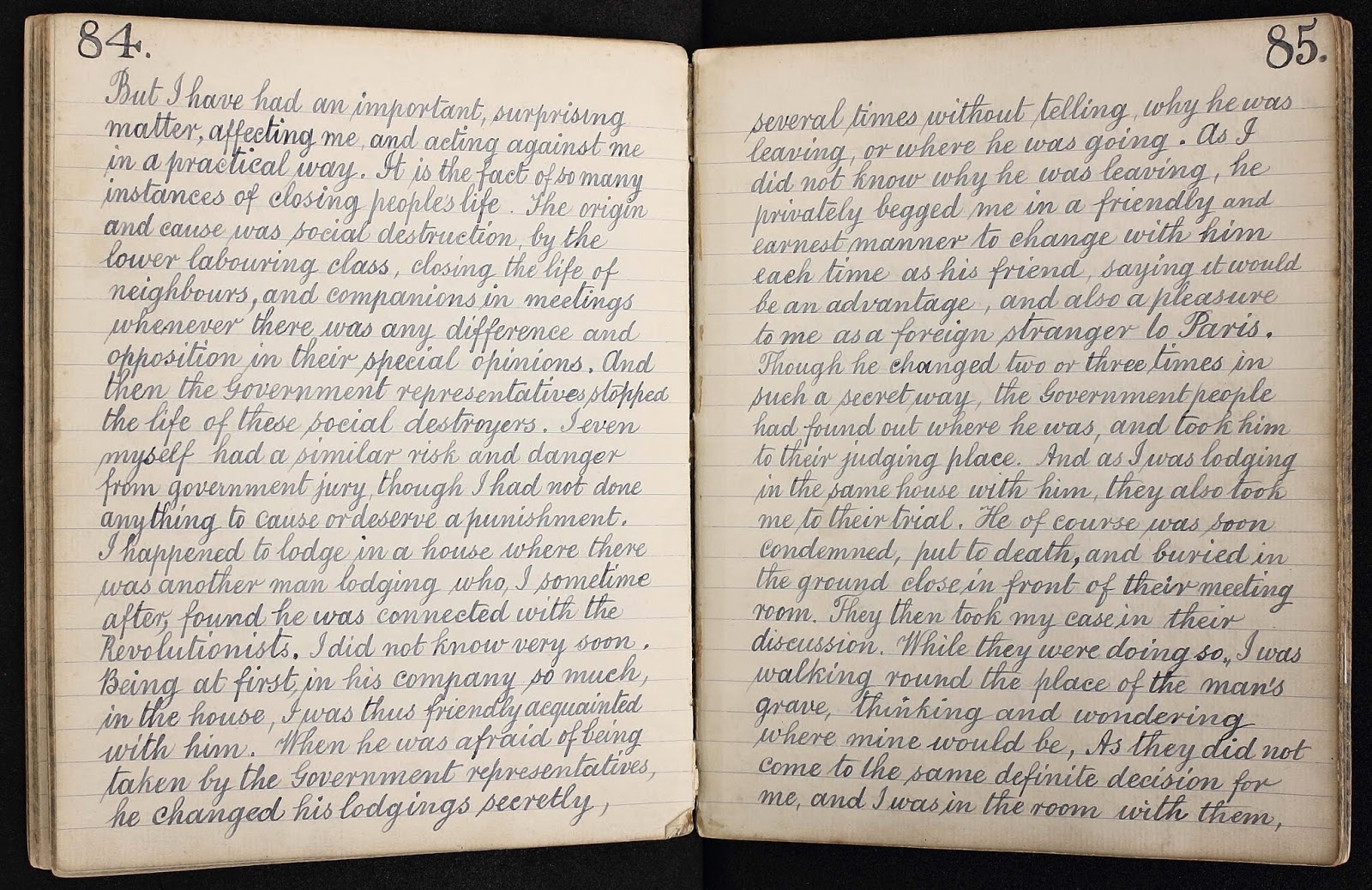

Two particularly interesting moments describe the intersection of Ayrton’s life with major public figures and events. He runs into Charles Dickens on the street, and later, in a fascinating moment, gets caught up with the Paris Commune uprising. On page 84, he tells of how this all began: “I happened to lodge in a house where there was another man lodging who, I sometime after, found he was connected with the Revolutionists.”

Two particularly interesting moments describe the intersection of Ayrton’s life with major public figures and events. He runs into Charles Dickens on the street, and later, in a fascinating moment, gets caught up with the Paris Commune uprising. On page 84, he tells of how this all began: “I happened to lodge in a house where there was another man lodging who, I sometime after, found he was connected with the Revolutionists.”

Ayrton is a great observer of those around him: “As my great subject in all my experience of life, has always been to observe earnestly and interestedly the various circumstances of the population, wherever I might be so that I might notice and learn all the various doubts, difficulties, and problems of life, and also all their conduct, with regard to the natural world, the Universe and their own humanity.”(83)

Ayrton is a great observer of those around him: “As my great subject in all my experience of life, has always been to observe earnestly and interestedly the various circumstances of the population, wherever I might be so that I might notice and learn all the various doubts, difficulties, and problems of life, and also all their conduct, with regard to the natural world, the Universe and their own humanity.”(83)

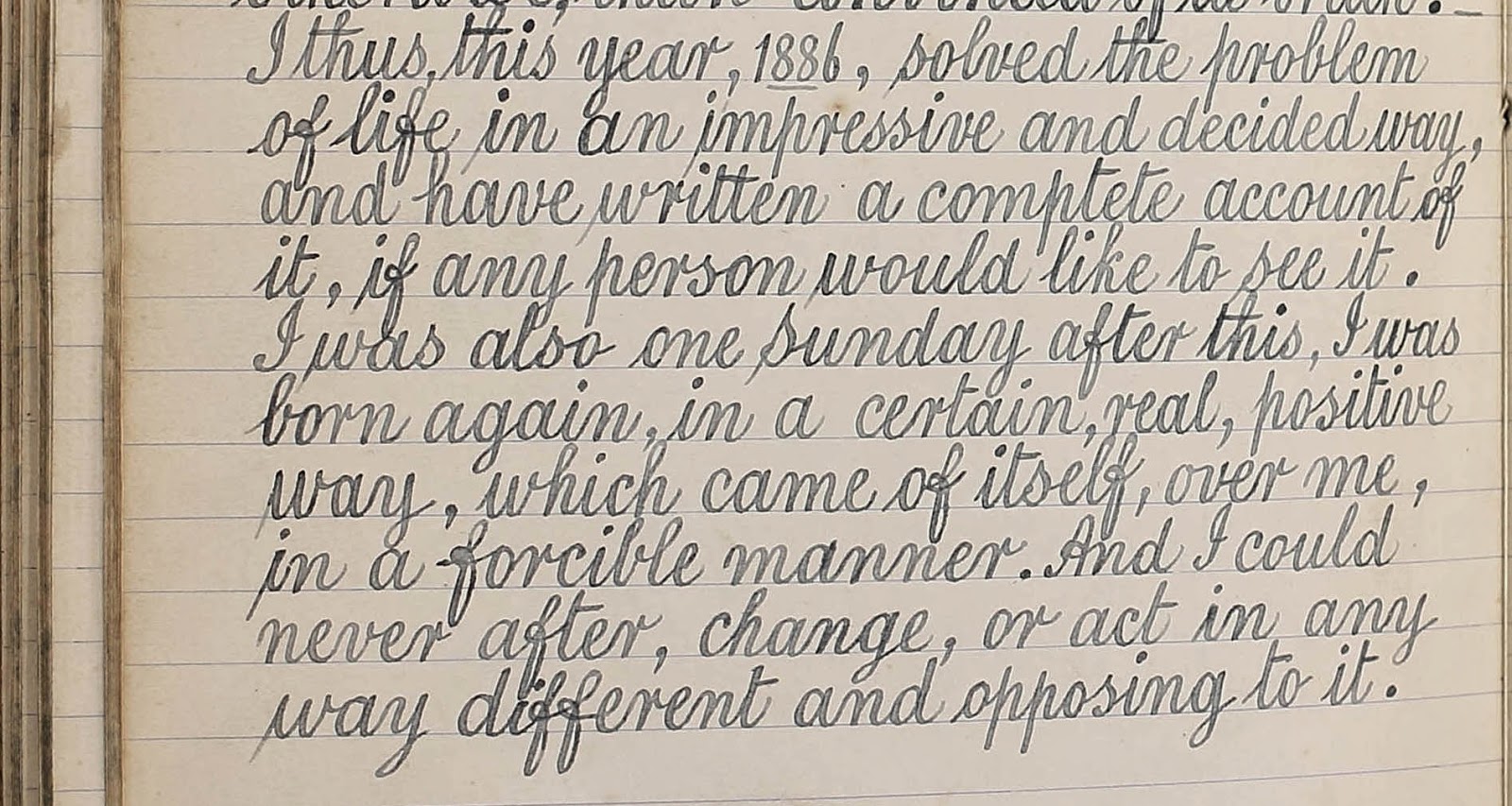

Ultimately, he is searching for the meaning of life, something which he finds, though does not explain in this diary: “I never heard from any leaders and teachers, a real correct, and complete solution of the problem of life. It thus naturally enforced itself upon me for a thorough solution, and ever remained in a prominent position in my mind. I was thus mentally compelled to solve it for myself in A.D. 1886 in Manchester, when I had been appointed a Churchwarden, at St. Clements Church in Greenheys” (99).

Ultimately, he is searching for the meaning of life, something which he finds, though does not explain in this diary: “I never heard from any leaders and teachers, a real correct, and complete solution of the problem of life. It thus naturally enforced itself upon me for a thorough solution, and ever remained in a prominent position in my mind. I was thus mentally compelled to solve it for myself in A.D. 1886 in Manchester, when I had been appointed a Churchwarden, at St. Clements Church in Greenheys” (99).

While Ayrton’s language leans towards the stiff and formal, his style of writing belies the open and unflinching way in which he bares his soul. Readers are privileged to read this man’s thorough examination of his own self and to watch how, between descriptions of his business affairs and his frequent exhortations to God, Ayrton frequently does battle with his own lesser inclinations.

While Ayrton’s language leans towards the stiff and formal, his style of writing belies the open and unflinching way in which he bares his soul. Readers are privileged to read this man’s thorough examination of his own self and to watch how, between descriptions of his business affairs and his frequent exhortations to God, Ayrton frequently does battle with his own lesser inclinations.

This diary was purchased with a grant from the Ann and Abe Effron Fund, and it is available digitally on the Internet Archive.