Once Upon a Time… Rare and Fine Press Editions of Fairy Tales

May 2, 2014

Description by Surella Evanor Seelig, Archives and Special Collections Coordinator

“I liked magic, the unreal, the more than real.”[1]

“The best single description I know of the world of the fairy tale is that of Max Lüthi who describes it as an abstract world, full of discrete, interchangeable people, objects and incidents, all of which are isolated and are nevertheless interconnected, in a kind of web or network of two-dimensional meaning. Everything in the tales appears to happen entirely by chance—and this has the strange effect of making it appear that nothing happens by chance, that everything is fated.”[2]

Brandeis University’s Special Collections is home to a number of rare and fine-press books of fairy tales. Some of these stories are familiar and others less so, though all are strikingly illustrated so as to heighten the unreality delivered by the text.

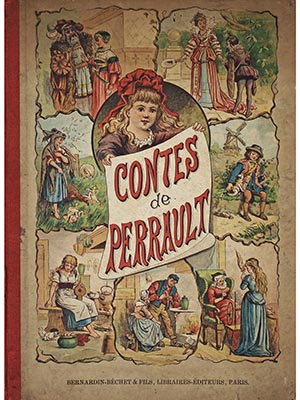

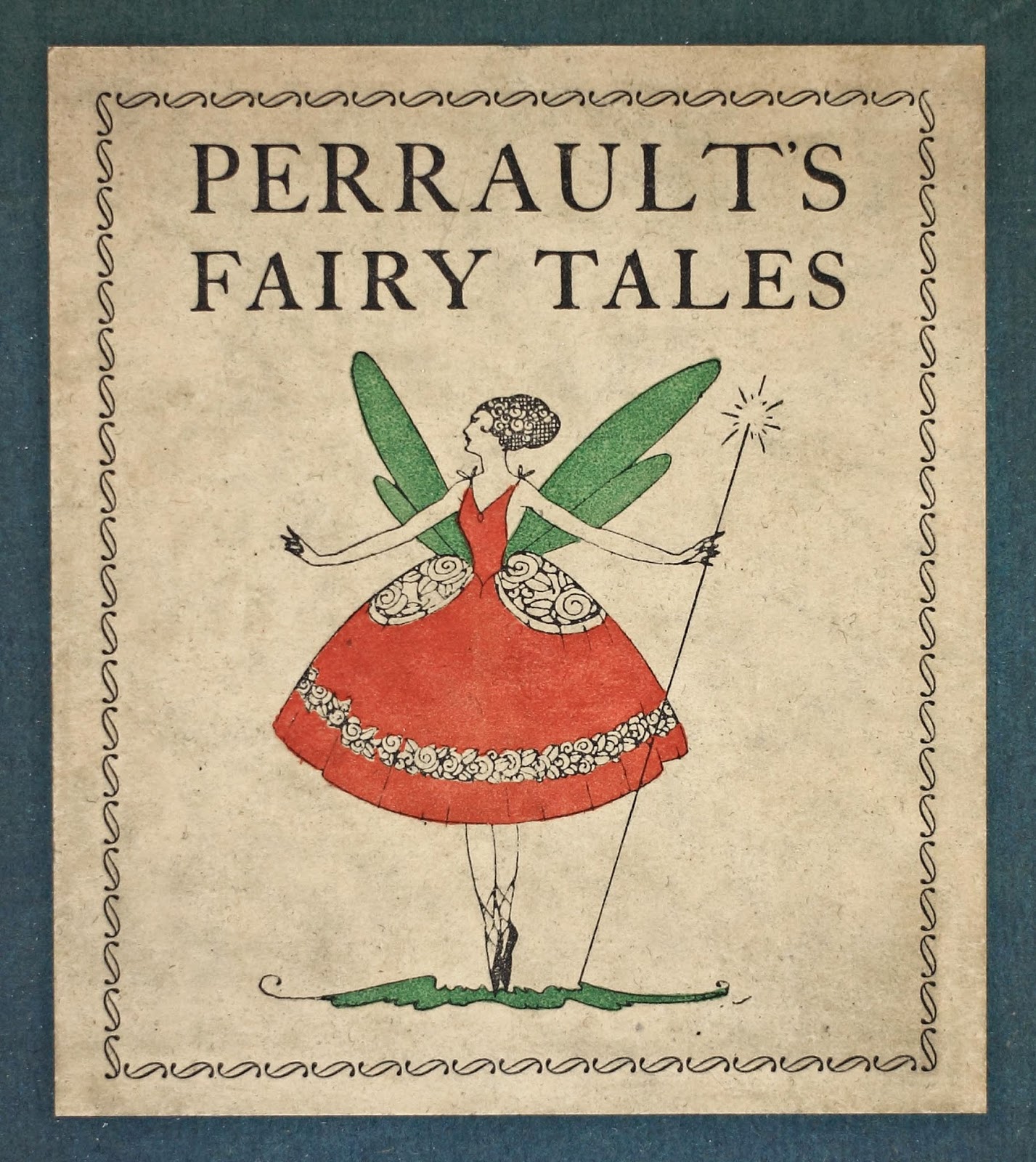

Brandeis University’s Special Collections is home to a number of rare and fine-press books of fairy tales. Some of these stories are familiar and others less so, though all are strikingly illustrated so as to heighten the unreality delivered by the text.It is well known that many of the stories we learned as children were less “written” than collected, massaged and crafted into text by their fabulists. The Grimms’ Hansel and Gretel, Rumpelstiltskin and Cinderella, for example, began as old German folk tales, and though the origins of Little Red Riding Hood, Blue Beard and Sleeping Beauty are debatable, they surely did not spring entirely from the mind of Charles Perrault himself. Versions of the stories Perrault wrote in the 17th century had been in existence for years before he forged them into “Les Contes de ma Mère l’Oye (Tales of Mother Goose).”

What is less well known is that authors quite often softened the original folk tales and made them “more suitable” for editions marketed to children. While we are all familiar with the sometimes frustrating Disneyfication of our favorite fairy stories as they are rendered toothless for the cartoon audience, even the Grimms were not averse to a little retouching in the name of good business. In fact, in response to public criticism the Grimms removed many a salacious plot point—though they shrewdly left in (and often increased) the violence.[3] The emphasized violence was not only a sure way to attract a younger audience; it also served as a useful tool for parents seeking to teach their children about right and wrong. Even modified though, it is the rare fairy tale that is intended only for a youthful audience, and many are often disturbing, heartbreaking, frightening and thrilling stories that have a great deal to offer the adult reader.

What is less well known is that authors quite often softened the original folk tales and made them “more suitable” for editions marketed to children. While we are all familiar with the sometimes frustrating Disneyfication of our favorite fairy stories as they are rendered toothless for the cartoon audience, even the Grimms were not averse to a little retouching in the name of good business. In fact, in response to public criticism the Grimms removed many a salacious plot point—though they shrewdly left in (and often increased) the violence.[3] The emphasized violence was not only a sure way to attract a younger audience; it also served as a useful tool for parents seeking to teach their children about right and wrong. Even modified though, it is the rare fairy tale that is intended only for a youthful audience, and many are often disturbing, heartbreaking, frightening and thrilling stories that have a great deal to offer the adult reader.

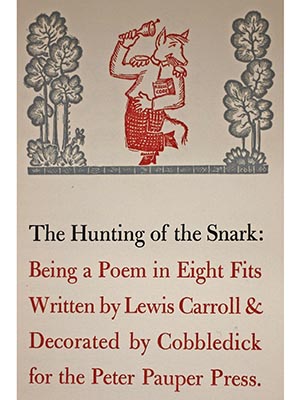

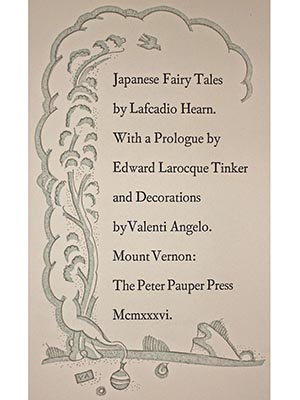

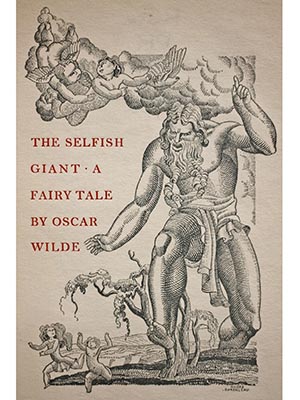

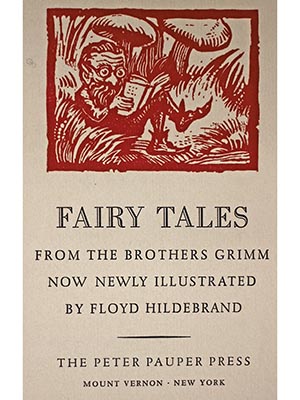

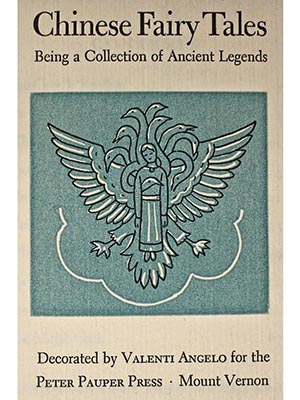

A number of the fine press editions held in Special Collections were donated to Brandeis by Henry and Hannah Hofheimer. These were published in limited runs by Peter Pauper Press and decorated by celebrated illustrators like Cobbledick, Valenti Angelo, Floyd Hildebrand and André Durenceau. They comprise the aforementioned “Grimm: Fairy Tales” (1931, English), Oscar Wilde’s “The Selfish Giant” (1932), and several collections of non-Western fables, such as “Chinese Fairy Tales: Being a Collection of Ancient Legends” (1938), “Persian Fairy Tales” (1939), and Lafacadio Hearn’s “Japanese Fairy Tales” (1936). Lewis Carroll’s “The Hunting of the Snark” (1939) and Edward Lear's “Nonsense Songs & Laughable Lyrics” (1935), which fall more in the camp of literary nonsense than fairy tale, were similarly aimed at adults as much as at children.

A number of the fine press editions held in Special Collections were donated to Brandeis by Henry and Hannah Hofheimer. These were published in limited runs by Peter Pauper Press and decorated by celebrated illustrators like Cobbledick, Valenti Angelo, Floyd Hildebrand and André Durenceau. They comprise the aforementioned “Grimm: Fairy Tales” (1931, English), Oscar Wilde’s “The Selfish Giant” (1932), and several collections of non-Western fables, such as “Chinese Fairy Tales: Being a Collection of Ancient Legends” (1938), “Persian Fairy Tales” (1939), and Lafacadio Hearn’s “Japanese Fairy Tales” (1936). Lewis Carroll’s “The Hunting of the Snark” (1939) and Edward Lear's “Nonsense Songs & Laughable Lyrics” (1935), which fall more in the camp of literary nonsense than fairy tale, were similarly aimed at adults as much as at children.

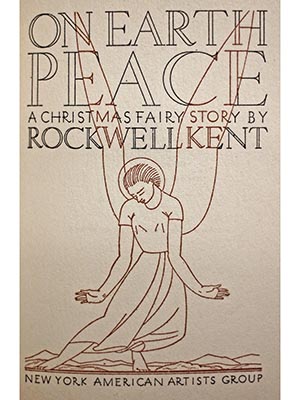

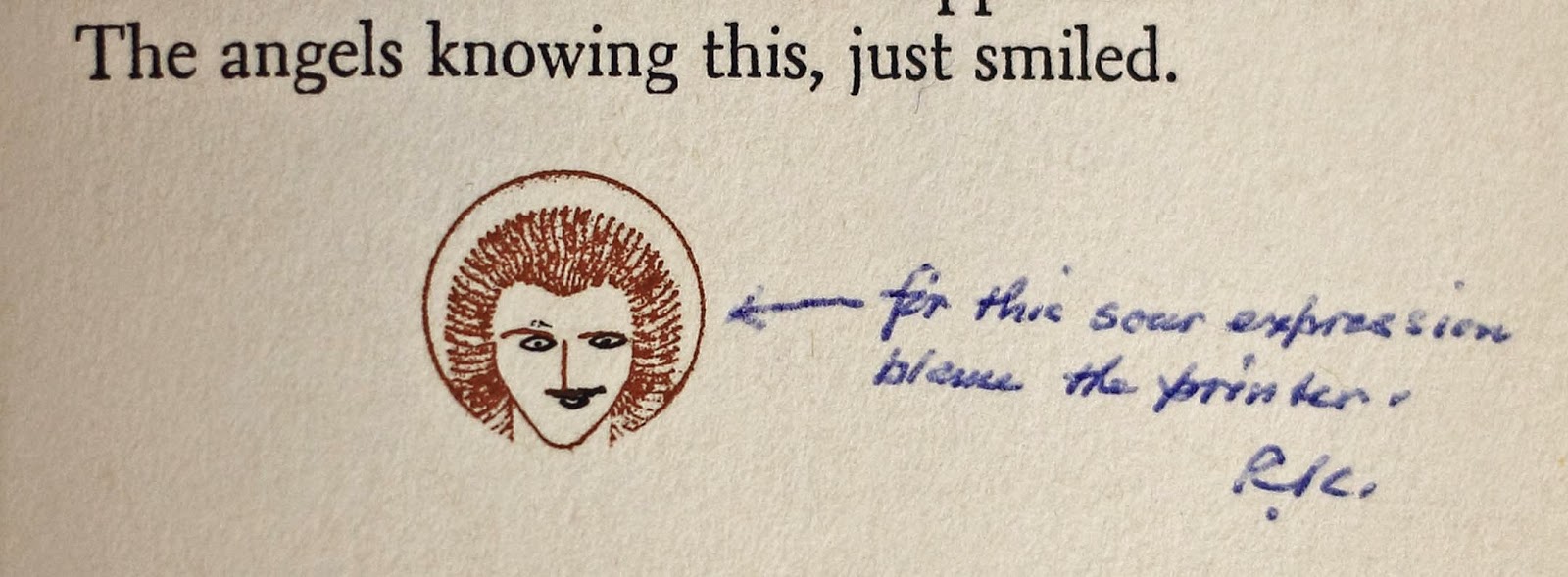

Some of the lesser-known fairy tale collections in our holdings include: “Stories for Children (Lu Lu tales): A Book for All Little Girls and Boys” (1853), edited by Mrs. Colman of Brookline, Massachusetts, and “Fairy Frisket,” an 1874 publication in which Charlotte Maria Tucker (writing as “A.L.O.E.” (A Lady of England), introduced the youth of her day to the world of science through whimsical stories of children taught by a fairy and turning into the insects that are the objects of their study.[4] Rockwell Kent, famed for his stunning illustrations, created his own fairy tale: “On Earth, Peace: A Christmas Fairy Story,” published in 1942 by the New York American Artists Group. Our copy, signed in 1961 with a gift note to Bern Dibner (who in turn donated it to Brandeis), includes an amusing and rather ironic handwritten note by the author/illustrator relating to the expression on the face of one of his characters.

Some of the lesser-known fairy tale collections in our holdings include: “Stories for Children (Lu Lu tales): A Book for All Little Girls and Boys” (1853), edited by Mrs. Colman of Brookline, Massachusetts, and “Fairy Frisket,” an 1874 publication in which Charlotte Maria Tucker (writing as “A.L.O.E.” (A Lady of England), introduced the youth of her day to the world of science through whimsical stories of children taught by a fairy and turning into the insects that are the objects of their study.[4] Rockwell Kent, famed for his stunning illustrations, created his own fairy tale: “On Earth, Peace: A Christmas Fairy Story,” published in 1942 by the New York American Artists Group. Our copy, signed in 1961 with a gift note to Bern Dibner (who in turn donated it to Brandeis), includes an amusing and rather ironic handwritten note by the author/illustrator relating to the expression on the face of one of his characters.

These and more fantastical stories can be found in Brandeis’ Special Collections.

Notes

- and

- Byatt, A.S. “Introduction by A.S. Byatt.” “The Annotated Brothers Grimm” Edited by Maria Tatar. New York: W.W. and Co., 2004, xvii and xix, respectively.

- Tatar, Maria. “Reading the Grimms’ Children’s Stories and Household Tales.” “The Annotated Brothers Grimm” Edited by Maria Tatar. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2004, xliii-xlv.

- Zimmerman, Virginia. “Natural History on Blocks, in Bodies, and on the Hearth: Juvenile Science Literature and Games, 1850–1875.” “Configurations” 19:3, Fall 2011, pp. 407-430.