William Lloyd Garrison Collection

October 27, 2011

Description by Anne Marie Reardon, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in History

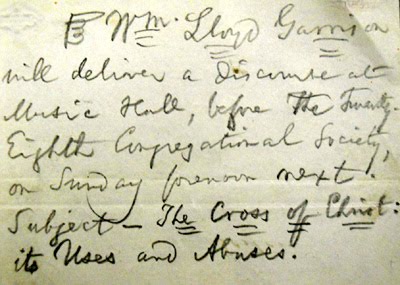

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis is fortunate to house a small but intriguing collection of papers relating to Boston’s famed radical white abolitionist and newspaper publisher, William Lloyd Garrison.[1] A gift of Philip D. Sang, the William Lloyd Garrison collection consists of lecture and editorial manuscripts, handwritten lecture notes and numerous letters from Garrison, his family and his many supporters (including numerous well-known 19th-century reformers). Written before, during and after the American Civil War, these papers illuminate Garrison’s tireless efforts to abolish slavery and inequality in the United States.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis is fortunate to house a small but intriguing collection of papers relating to Boston’s famed radical white abolitionist and newspaper publisher, William Lloyd Garrison.[1] A gift of Philip D. Sang, the William Lloyd Garrison collection consists of lecture and editorial manuscripts, handwritten lecture notes and numerous letters from Garrison, his family and his many supporters (including numerous well-known 19th-century reformers). Written before, during and after the American Civil War, these papers illuminate Garrison’s tireless efforts to abolish slavery and inequality in the United States.

In speaking of William Lloyd Garrison, historian David W. Blight has said “there is no more significant reformer in the 19th century.”[2] Similarly, Henry Mayer, Garrison’s modern biographer, declared that “Garrison occupies a place as central in the history of the nineteenth century as that of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the history of the twentieth.”[3] Yet Garrison’s upbringing far from predicted his future leadership. William Lloyd Garrison was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, on December 12, 1805. Fathered by an immigrant sailor who soon abandoned his family, Garrison was raised in poverty, gaining most of his education only as a teenager when a printer’s apprenticeship afforded him access to texts with which to educate himself. From an early age, Garrison was also influenced by his mother’s unswerving Baptist beliefs in Christian morality and righteousness—beliefs that became the root of Garrison’s future championing of universal civil rights.

In speaking of William Lloyd Garrison, historian David W. Blight has said “there is no more significant reformer in the 19th century.”[2] Similarly, Henry Mayer, Garrison’s modern biographer, declared that “Garrison occupies a place as central in the history of the nineteenth century as that of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the history of the twentieth.”[3] Yet Garrison’s upbringing far from predicted his future leadership. William Lloyd Garrison was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, on December 12, 1805. Fathered by an immigrant sailor who soon abandoned his family, Garrison was raised in poverty, gaining most of his education only as a teenager when a printer’s apprenticeship afforded him access to texts with which to educate himself. From an early age, Garrison was also influenced by his mother’s unswerving Baptist beliefs in Christian morality and righteousness—beliefs that became the root of Garrison’s future championing of universal civil rights.

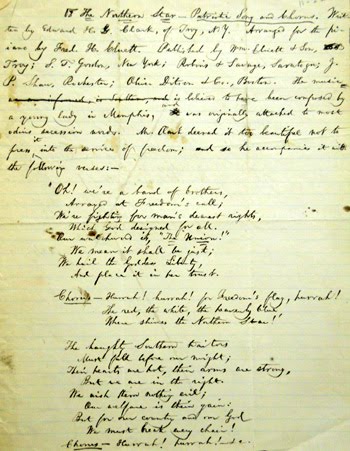

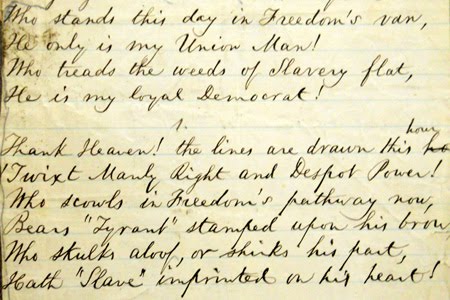

William Lloyd Garrison’s strong moral standards led him to become an active and vocal abolitionist at a very early age. By 1830, Garrison had shifted to the most radical of abolitionist views, calling for the immediate, complete and universal emancipation of all slaves (by contrast, many early abolitionists supported more gradual emancipation). To further his cause, on January 1, 1831, Garrison printed the inaugural edition of The Liberator, an anti-slavery newspaper. Soon after, Garrison helped to found the New England Anti-Slavery Society, and then, in 1833, the broader American Anti-Slavery Society. The Liberator immediately began to promote the platforms of these organizations. Gaining popularity and notoriety in equal measure over the following decades, The Liberator was published weekly without break through December 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, finally abolishing slavery in the United States.

William Lloyd Garrison’s strong moral standards led him to become an active and vocal abolitionist at a very early age. By 1830, Garrison had shifted to the most radical of abolitionist views, calling for the immediate, complete and universal emancipation of all slaves (by contrast, many early abolitionists supported more gradual emancipation). To further his cause, on January 1, 1831, Garrison printed the inaugural edition of The Liberator, an anti-slavery newspaper. Soon after, Garrison helped to found the New England Anti-Slavery Society, and then, in 1833, the broader American Anti-Slavery Society. The Liberator immediately began to promote the platforms of these organizations. Gaining popularity and notoriety in equal measure over the following decades, The Liberator was published weekly without break through December 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, finally abolishing slavery in the United States.

Over the course of its 34-year run, The Liberator focused primarily on anti-slavery issues and events. In Brandeis’s Garrison collection, one can follow the progression of these matters through Garrison’s often fiery notes, editorials and speeches, which praise various anti-slavery causes and supporters even as they rail against anti-slavery detractors.

Over the course of its 34-year run, The Liberator focused primarily on anti-slavery issues and events. In Brandeis’s Garrison collection, one can follow the progression of these matters through Garrison’s often fiery notes, editorials and speeches, which praise various anti-slavery causes and supporters even as they rail against anti-slavery detractors.

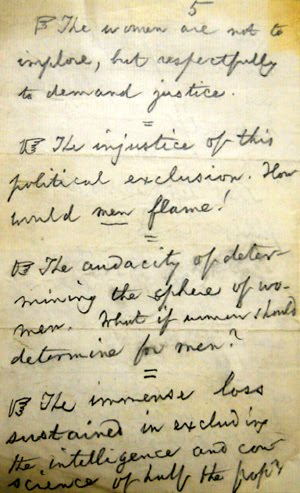

Similarly, the collection reflects Garrison’s practice of supporting many non-abolitionist causes that he felt were related to his greater goal of universal equality and civil rights. Garrison was an early champion of woman suffrage, as seen in his declaration: “where men only are allowed to vote, to say it is a government by, of and for the people is equally ridiculous.” Garrison also expressed his anticlerical views that “no man and no book be our master,” based in his belief that organized religion too often acted as a bulwark of slavery. Other writings in the collection detail Garrison’s long-held belief in pacifism and passive resistance; his briefer support of disunion (Northern secession) and election boycotts (to protest national support of slavery); his respect for spiritualism; his emphasis on temperance; and his unflagging conviction that African Americans should not only be free but also attain civil rights equal to those of all other Americans.

Similarly, the collection reflects Garrison’s practice of supporting many non-abolitionist causes that he felt were related to his greater goal of universal equality and civil rights. Garrison was an early champion of woman suffrage, as seen in his declaration: “where men only are allowed to vote, to say it is a government by, of and for the people is equally ridiculous.” Garrison also expressed his anticlerical views that “no man and no book be our master,” based in his belief that organized religion too often acted as a bulwark of slavery. Other writings in the collection detail Garrison’s long-held belief in pacifism and passive resistance; his briefer support of disunion (Northern secession) and election boycotts (to protest national support of slavery); his respect for spiritualism; his emphasis on temperance; and his unflagging conviction that African Americans should not only be free but also attain civil rights equal to those of all other Americans.

Some of the later writings in the Garrison collection show both Garrison’s prescient wisdom and his growing impatience over the speed of social and governmental change. As the Civil War was drawing to a close with Union victory, Garrison wrote:

We confess that we shudder at the thought that, possibly, through timidity or lack of principle, the present glorious opportunity to put an end to slavery may be allowed to pass unimproved by the Government, and that there may be a renewal or reconstruction of the old ‘covenant with death and agreement with hell,’ to the further demoralization of the nation, the longer supremacy of the Slave Power and the ultimate outbreak of another civil war with heavier judgments and under more appalling circumstances."

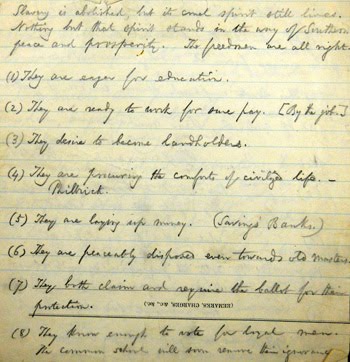

Even as the U.S. Congress adopted the Thirteenth Amendment banning slavery, Garrison wrote more about his fears for the future, warning that “slavery is abolished, but its cruel spirit still lives. Nothing but that spirit stands in the way of Southern peace and prosperity.” Though the U.S. Supreme Court’s segregationist “separate but equal” ruling and a full-fledged Jim Crow South were still decades off, Garrison’s words demonstrate his recognition that the abolition of slavery was only the first step in a long and difficult battle for universal civil rights.

Even as the U.S. Congress adopted the Thirteenth Amendment banning slavery, Garrison wrote more about his fears for the future, warning that “slavery is abolished, but its cruel spirit still lives. Nothing but that spirit stands in the way of Southern peace and prosperity.” Though the U.S. Supreme Court’s segregationist “separate but equal” ruling and a full-fledged Jim Crow South were still decades off, Garrison’s words demonstrate his recognition that the abolition of slavery was only the first step in a long and difficult battle for universal civil rights.

The Garrison collection speaks not only to the social causes Garrison advocated so vigorously, but also to the ramifications of such controversial opinions. While some saw Garrison as a visionary, or even a prophet, others saw him as a dangerous and heretical fanatic. Garrison was certainly not afraid to offend those he opposed. Thrown into jail for libel early in his abolitionist career, Garrison was unrepentant in his radical views. Despite a near-lynching by a mob in Boston in 1835, Garrison continued to be outspoken, both in person and in print. Included in the Garrison collection is a note expressing Garrison’s outrage over a newspaper’s downplayed account of a mob attack on a Garrison-led meeting. Other writings in the collection consist of angry rebuttals of ministers, government leaders and businessmen who opposed Garrison.

The Garrison collection speaks not only to the social causes Garrison advocated so vigorously, but also to the ramifications of such controversial opinions. While some saw Garrison as a visionary, or even a prophet, others saw him as a dangerous and heretical fanatic. Garrison was certainly not afraid to offend those he opposed. Thrown into jail for libel early in his abolitionist career, Garrison was unrepentant in his radical views. Despite a near-lynching by a mob in Boston in 1835, Garrison continued to be outspoken, both in person and in print. Included in the Garrison collection is a note expressing Garrison’s outrage over a newspaper’s downplayed account of a mob attack on a Garrison-led meeting. Other writings in the collection consist of angry rebuttals of ministers, government leaders and businessmen who opposed Garrison.

Garrison’s critics were not just from the pro-slavery camp. Garrison’s demands for moral perfectionism over pragmaticism, along with his insistence on friends’ loyalty to each and every one of his own radical beliefs, caused him to lose many of his initial supporters. Notes, letters and lectures in the Garrison collection give testament to the fact that Garrison was unafraid of publicly criticizing, even denouncing, peers in the anti-slavery cause when he felt they strayed from the “proper” course.

Garrison’s critics were not just from the pro-slavery camp. Garrison’s demands for moral perfectionism over pragmaticism, along with his insistence on friends’ loyalty to each and every one of his own radical beliefs, caused him to lose many of his initial supporters. Notes, letters and lectures in the Garrison collection give testament to the fact that Garrison was unafraid of publicly criticizing, even denouncing, peers in the anti-slavery cause when he felt they strayed from the “proper” course.

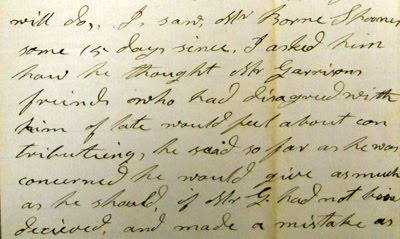

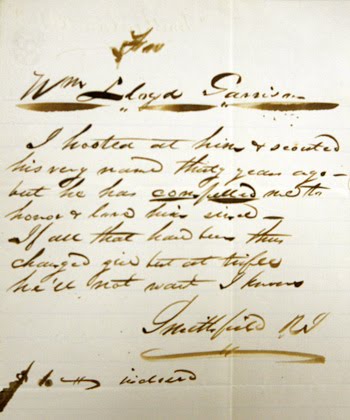

In 1865, Garrison’s contentious and uncompromising beliefs finally led him and the American Anti-Slavery Society (along with a number of Garrison’s former friends) to go their separate ways. A subsequent 1866 testimonial drive dedicated to providing Garrison with a retirement pension brought mixed results. Letters in the Garrison collection detail the reluctance of some former supporters to contribute to Garrison’s upkeep, in light of their recent disagreements. Letters of praise also abound from old abolitionist friends, including Caroline Weston (on behalf of Harriet Beecher Stowe), Rev. Samuel J. May, Jr., James M. McKim and Edmund Quincy, among others. In addition, a public announcement of the testimonial drive resulted in support from some unexpected sources, including Union General Francis C. Barlow, who wrote of “how much reverence and how grateful I feel to Mr. Garrison and those who have worked with him.” Perhaps the most surprising of the letters came from an anonymous contributor, who wrote how he had “hooted” at Garrison thirty years before, but was “compelled… to honor and laud him since.”

In 1865, Garrison’s contentious and uncompromising beliefs finally led him and the American Anti-Slavery Society (along with a number of Garrison’s former friends) to go their separate ways. A subsequent 1866 testimonial drive dedicated to providing Garrison with a retirement pension brought mixed results. Letters in the Garrison collection detail the reluctance of some former supporters to contribute to Garrison’s upkeep, in light of their recent disagreements. Letters of praise also abound from old abolitionist friends, including Caroline Weston (on behalf of Harriet Beecher Stowe), Rev. Samuel J. May, Jr., James M. McKim and Edmund Quincy, among others. In addition, a public announcement of the testimonial drive resulted in support from some unexpected sources, including Union General Francis C. Barlow, who wrote of “how much reverence and how grateful I feel to Mr. Garrison and those who have worked with him.” Perhaps the most surprising of the letters came from an anonymous contributor, who wrote how he had “hooted” at Garrison thirty years before, but was “compelled… to honor and laud him since.”

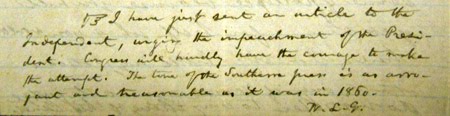

William Lloyd Garrison retired in 1865, closing down The Liberator and resigning his presidency of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Yet, as the Garrison collection confirms, the activist relinquished neither his causes nor his pen in the last years of his life. In an 1866 letter to his son Frank, Garrison wrote, “I have just sent an article to the Independent, urging the impeachment of the President. Congress will hardly have the courage to make the attempt. The tone of the Southern press is as arrogant and treasonable as it was in 1860.” Even in retirement, with declining health, Garrison maintained his radical progressive stance, though it would be two years before Congress agreed with him and successfully impeached President Andrew Johnson.

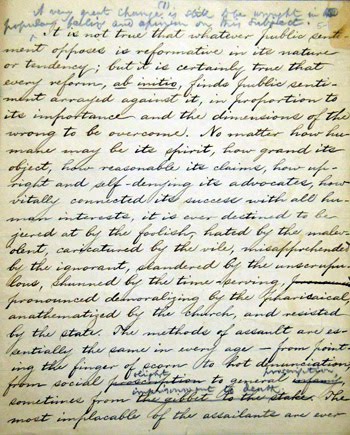

In a note within the Garrison collection, Garrison defended his uncompromising lifelong commitment to reform, in face of great opposition, saying:

"It is not true that whatever public sentiment opposes is reformative in its nature or tendency; but it is certainly true that every reform, ab initio, finds public sentiment arrayed against it, in proportion to its importance and the dimensions of the wrong to be overcome."

To his death in 1879, William Lloyd Garrison believed wholeheartedly in the all-encompassing importance of universal civil rights. Despite the critiques of friends and foes, Garrison thus remained unapologetic in his actions and writings. Brandeis’s William Lloyd Garrison collection offers a small window on Garrison’s radical views, along with the controversies they raised. In turn, through this single abolitionist’s example, the collection reveals much about the means and determination necessary to achieve lasting social reform.

Notes

- For general background and discussion regarding William Lloyd Garrison, see Henry Mayer, “All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery” (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), and James Brewer Stewart, ed., “William Lloyd Garrison at Two Hundred” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).

- David W. Blight, “William Lloyd Garrison at Two Hundred: His Radicalism and His Legacy for Our Time,” in William Lloyd Garrison at Two Hundred, 1.

- Mayer, “All on Fire,” 631.