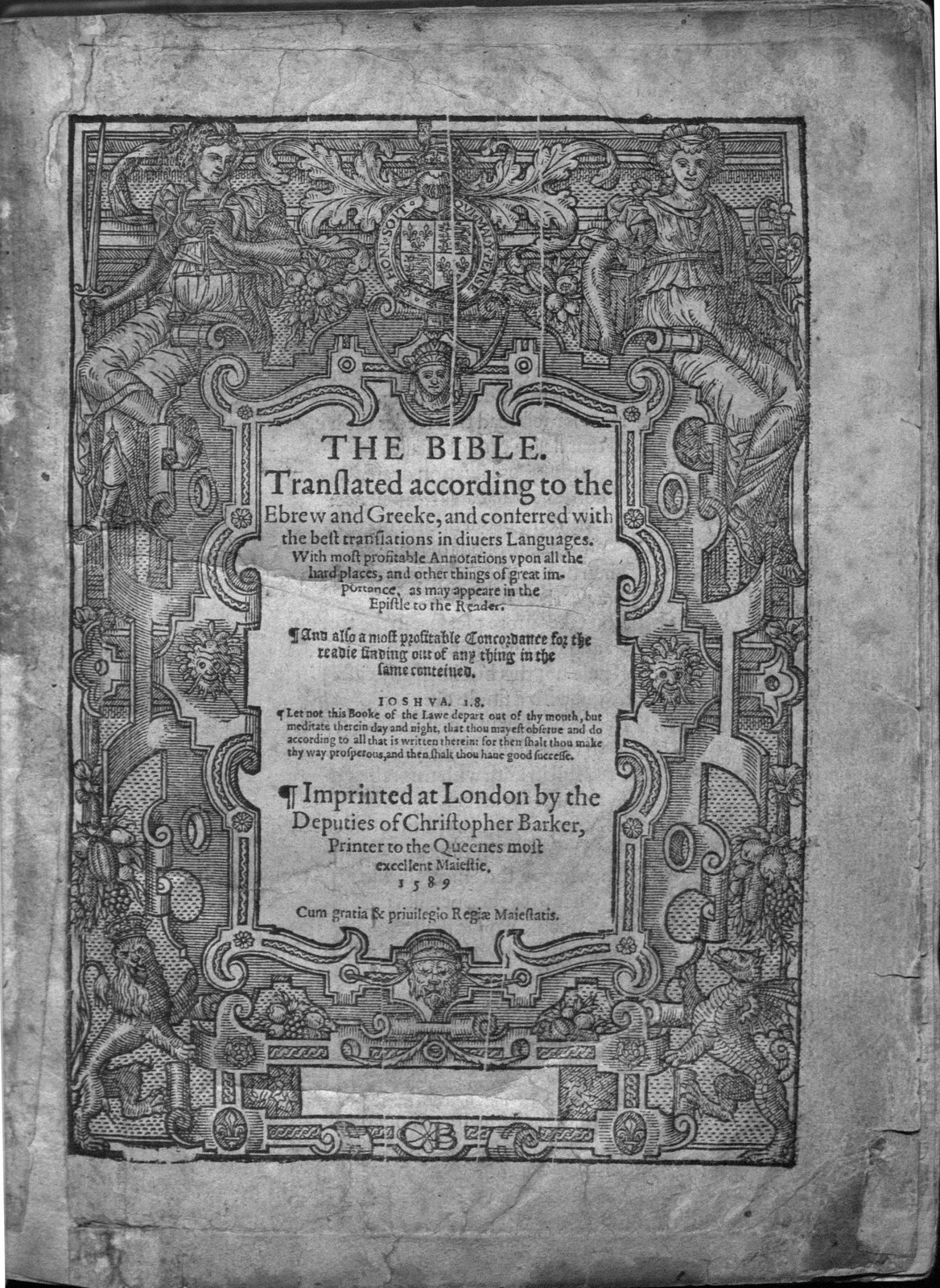

Geneva Bible. London: Deputies of Christopher Barker, Printer to the Queenes Most Excellent Majestie, 1589.

December 17, 2007

Description by Adam Rutledge, Senior University Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in English and American literature

The English Geneva Bible, published in completed form in 1560, was issued at a time when the Roman Catholic Church had banned all vernacular translations of the Bible. Building on the work of William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale, whose early English translation appeared in 1535, the Geneva Bible was the first English Bible to draw its translation entirely from the original Greek and Hebrew texts, rather than from the Latin Vulgate. Its title derives from the fact that the translation was prepared by English reformers living in the Protestant stronghold of Geneva, Switzerland, who had fled England during the reign of the Roman Catholic queen, Mary the First. It is also often called the “Breeches Bible” on account of its unusual translation of Genesis 3:7, in which Adam and Eve are described as fashioning “breeches” to cover their nakedness. This is the edition of the Bible that Shakespeare read, and from which he quotes in his plays. Its influence continues to the present day through its incorporation in the King James translation, which remained the standard English Bible for several centuries.

The English Geneva Bible, published in completed form in 1560, was issued at a time when the Roman Catholic Church had banned all vernacular translations of the Bible. Building on the work of William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale, whose early English translation appeared in 1535, the Geneva Bible was the first English Bible to draw its translation entirely from the original Greek and Hebrew texts, rather than from the Latin Vulgate. Its title derives from the fact that the translation was prepared by English reformers living in the Protestant stronghold of Geneva, Switzerland, who had fled England during the reign of the Roman Catholic queen, Mary the First. It is also often called the “Breeches Bible” on account of its unusual translation of Genesis 3:7, in which Adam and Eve are described as fashioning “breeches” to cover their nakedness. This is the edition of the Bible that Shakespeare read, and from which he quotes in his plays. Its influence continues to the present day through its incorporation in the King James translation, which remained the standard English Bible for several centuries.

While the 1560 edition was issued in modern, Roman type, a minority of editions were printed using the older Gothic-style type, including this edition from 1589. The pages of this volume are quite dark compared to other books of a similar age, largely as a result of the lower-quality paper used in the printing of this text. This was not a mistake, for the intention of the Protestant reformers in preparing this translation was to make the Bible both more accessible and more affordable for lay Christians, although the price would still have been out of reach for the majority of the population.

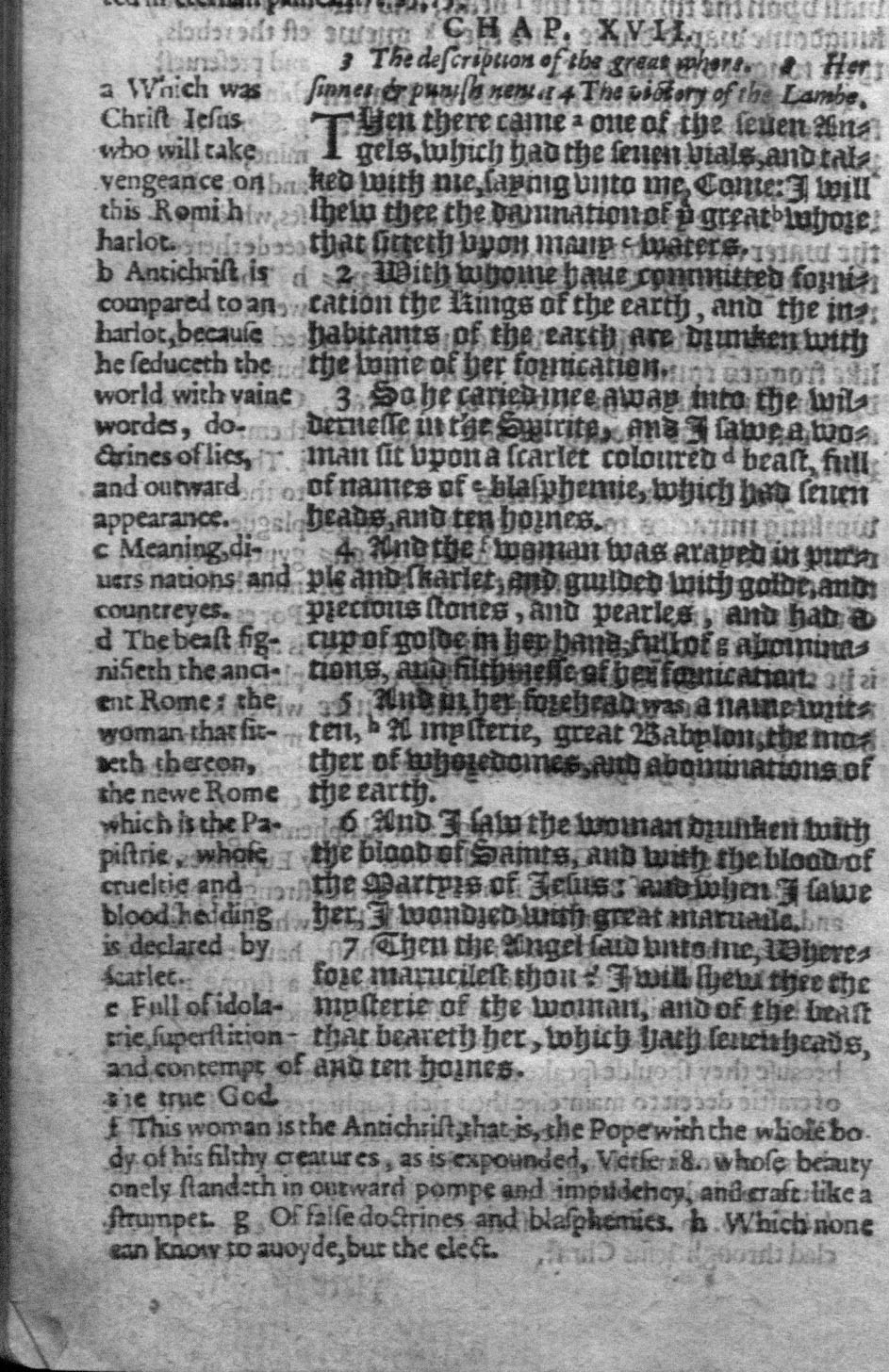

As part of the Protestant teaching that every Christian had the ability to read and interpret the Bible for himself or herself, another significant innovation in the Geneva Bible is the presence of printed marginal notes, offering aids to the reader for understanding the text. These range from translators’ explanations for their choice of words to theological exposition, and it is the latter that exhibit this edition’s strong anti-Catholic bias. Attacks on the Roman Catholic Church are especially prevalent in the marginal notes to the book of Revelation, one example of which may be seen in the explanation for Rev. 17:3-4, found in notes (d) and (f) in the margin.

Geneva Bible – Revelation 17:3-4

Geneva Bible – Revelation 17:3-4

3 So he caried mee away into the wildernesse in the Spirite, and I sawe a woman sit upon a scarlet coloured (d) beast, full of names of blasphemie, which had seven heads and ten hornes.

4 And the (f) woman was arayed in purple and skarlet, and guilded with golde, and precious stones, and pearles, and had a cup of golde in her hand; full of abominations, and filthinesse of her fornication.

(d) The beast signifieth the ancient Rome; the woman that sitteth thereon, the newe Rome which is the Papistrie, whose crueltie and bloodshedding is declared by scarlet.

(f) This woman is the Antichrist, that is, the Pope with the whole body of his filthy creatures, as is expounded, Verse 18. whose beauty onely standeth in outward pompe and impudency, and craft like a strumpet.

Further Reading

Geneva Bible, 1589. Main Library – Special Collections – Rare BS170 1589.

A copy of this edition in the British Library is also available online through LOUIS (search “Geneva Bible electronic resource”). Brandeis also owns another copy, from 1599 (Rare BS170 1599), and a modern facsimile of the 1st edition of 1560 (Rare BS170 1560a).

Norton, David. A textual history of the King James Bible. (NY : Cambridge UP, 2005) [BS186 .N67 2005]

Hammond, Gerald. The making of the English Bible. (Manchester, England : Carcanet New Press, 1982)