The Walter F. and Alice Gorham Collection of Early Music Imprints

December 30, 2008

Description by Sarah Mead, Associate Professor of the Practice of Music and Director of the Early Music Ensemble

The development of music printing at the onset of the 16th century changed the European musical world. Before Petrucci’s first printed collection in 1501, written music was available only to those who had the time or the money to copy it by hand. With the advent of printed music, new works could be disseminated quickly and across great distances.

The development of music printing at the onset of the 16th century changed the European musical world. Before Petrucci’s first printed collection in 1501, written music was available only to those who had the time or the money to copy it by hand. With the advent of printed music, new works could be disseminated quickly and across great distances.

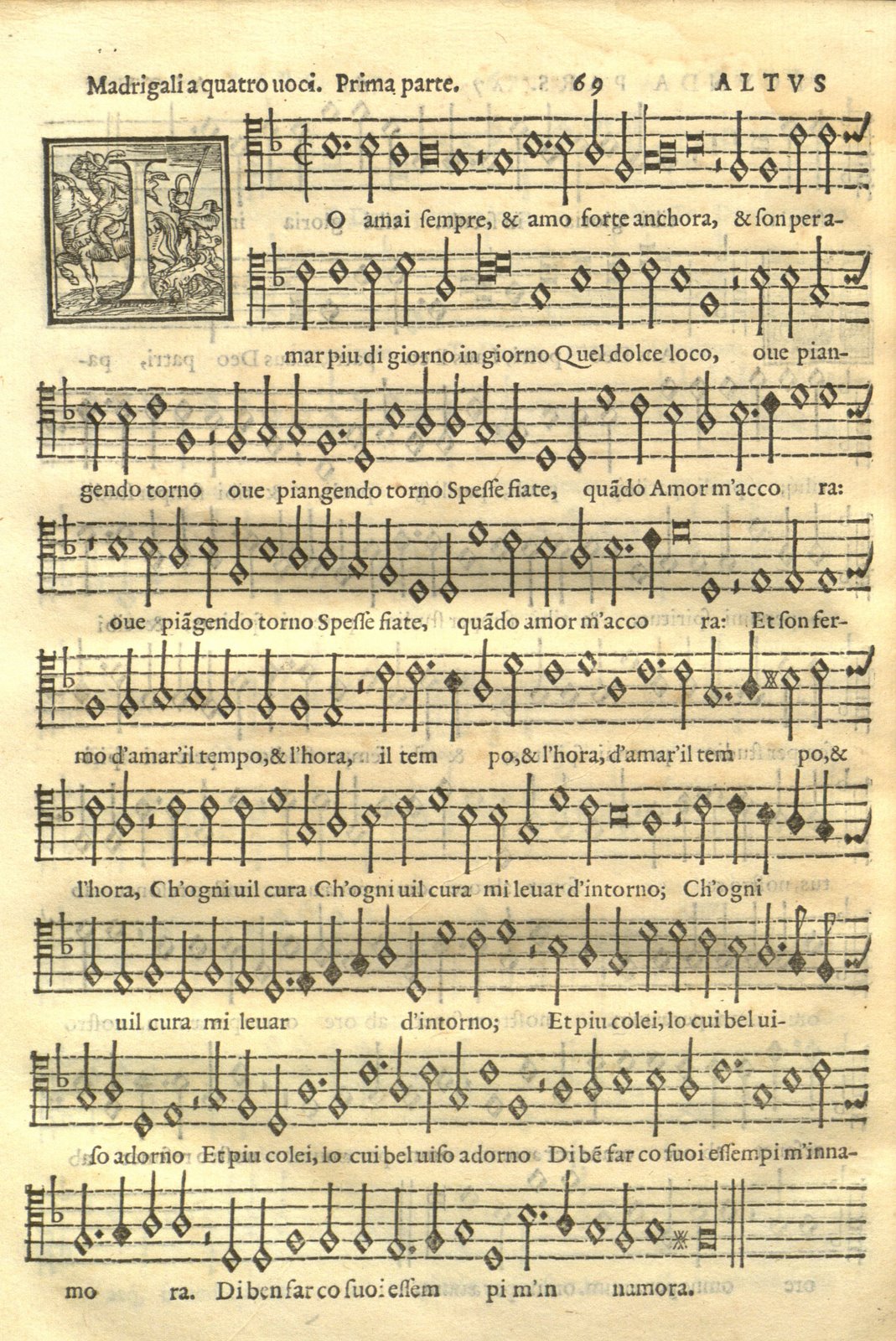

An even greater boost to the publication of music came with the development of type that contained both the note and a complete set of staff lines. Petrucci’s beautiful publications depended on a laborious process in which the staff lines, notes and text were each laid down with separate impressions, requiring painstaking precision. The new type enabled a single-impression process, making affordable music available to many more customers. The interrupted lines and blocky presentation were a small price to pay for greater availability. The educated classes could now emulate the nobility, purchasing the latest compositions and making music in their homes. Lovers of music—amateurs in the best sense—perfected their skills in singing and playing. Composers, freed from their dependence on courtly posts, could now profit directly from their work and also improve their job prospects through enhanced reputations (though patrons were still a necessity).

The second half of the 16th century saw a flowering of music publishing; the market for chamber music helped drive the growth of the madrigal and motet as forms well suited to home music-making, for both voices and instruments. In order that a group of singers or instrumentalists could easily read the notes, music was commonly published in separate partbooks, one book for each vocal or instrumental line. Since there was no conductor, a full score was unnecessary, and any one of the participants could supply the tactus—the pulse that keeps the parts together. The number of people who could participate in the music-making was determined by how many could see to share a part.

Any one publication, therefore, was made up of several partbooks, each one a thin pamphlet with no more than a paper cover. To protect and preserve them, the buyer could seek out a binder to make a more permanent cover. It often made sense to bind together several partbooks from different publications into a larger volume, each volume representing one voice or instrument. This highly practical system had one drawback: since the individual parts of one publication were not physically attached to one another, it was inevitable that over time these partbooks would become separated. Today it is rare to find a complete set of 16th-century partbooks intact. However, single partbooks do occasionally become available on the rare books market. Brandeis is very fortunate to have several of these books in its Gorham Collection.

Any one publication, therefore, was made up of several partbooks, each one a thin pamphlet with no more than a paper cover. To protect and preserve them, the buyer could seek out a binder to make a more permanent cover. It often made sense to bind together several partbooks from different publications into a larger volume, each volume representing one voice or instrument. This highly practical system had one drawback: since the individual parts of one publication were not physically attached to one another, it was inevitable that over time these partbooks would become separated. Today it is rare to find a complete set of 16th-century partbooks intact. However, single partbooks do occasionally become available on the rare books market. Brandeis is very fortunate to have several of these books in its Gorham Collection.

The Walter F. and Alice Gorham Collection of Early Music Imprints was established in 1998. In addition to treatises on the theory and performance of music, the collection includes eight partbooks, ranging from slim publications to large bound collections. These books contain parts to hundreds of pieces from the second half of the 16th century, published by some of the most influential printing houses of Italy and northern Europe. Brandeis scholars can work directly with the original texts, observing at close hand the details of printing and binding, watermarks and marginalia, that help to inform our understanding of the dissemination of music during this great flourishing of polyphony.

The Walter F. and Alice Gorham Collection of Early Music Imprints was established in 1998. In addition to treatises on the theory and performance of music, the collection includes eight partbooks, ranging from slim publications to large bound collections. These books contain parts to hundreds of pieces from the second half of the 16th century, published by some of the most influential printing houses of Italy and northern Europe. Brandeis scholars can work directly with the original texts, observing at close hand the details of printing and binding, watermarks and marginalia, that help to inform our understanding of the dissemination of music during this great flourishing of polyphony.

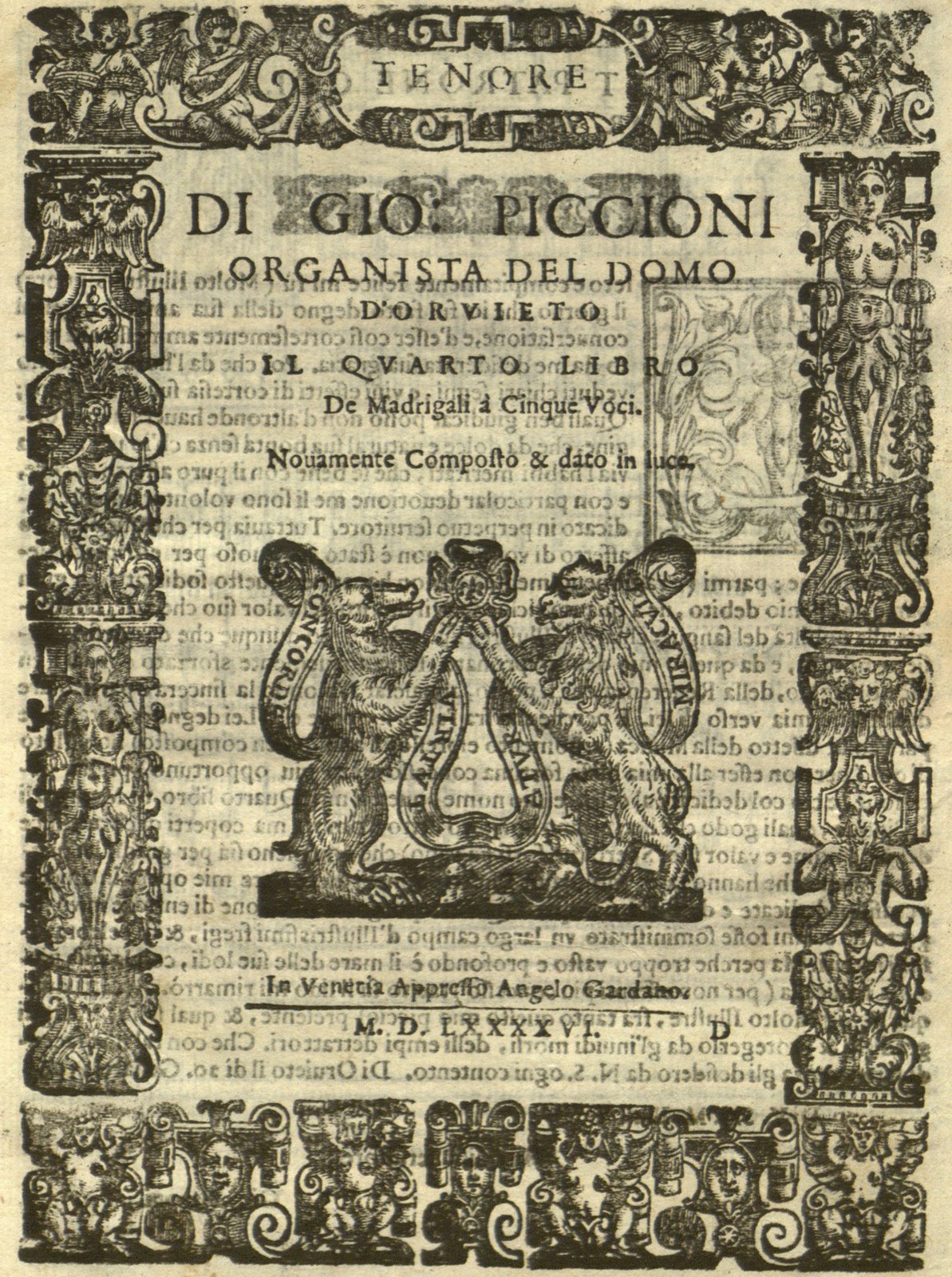

The tenor partbook from Giovanni Piccioni’s Il quarto libro de madrigali à cinque voci is an excellent example of how such a book would look before being taken to the bindery. The pages are sewn together and protected by a multicolored paper cover. The book contains the tenor parts to 21 madrigals. Although at least eight books of his madrigals were published in Venice during his lifetime, no modern editions of Piccioni’s music have yet been undertaken beyond one charming piece from a contemporary anthology. This book, the fourth of Piccioni’s madrigal collections, was brought out in 1596 by Angelo Gardano, a prolific Venetian publisher who produced almost 1000 publications over the course of his career.

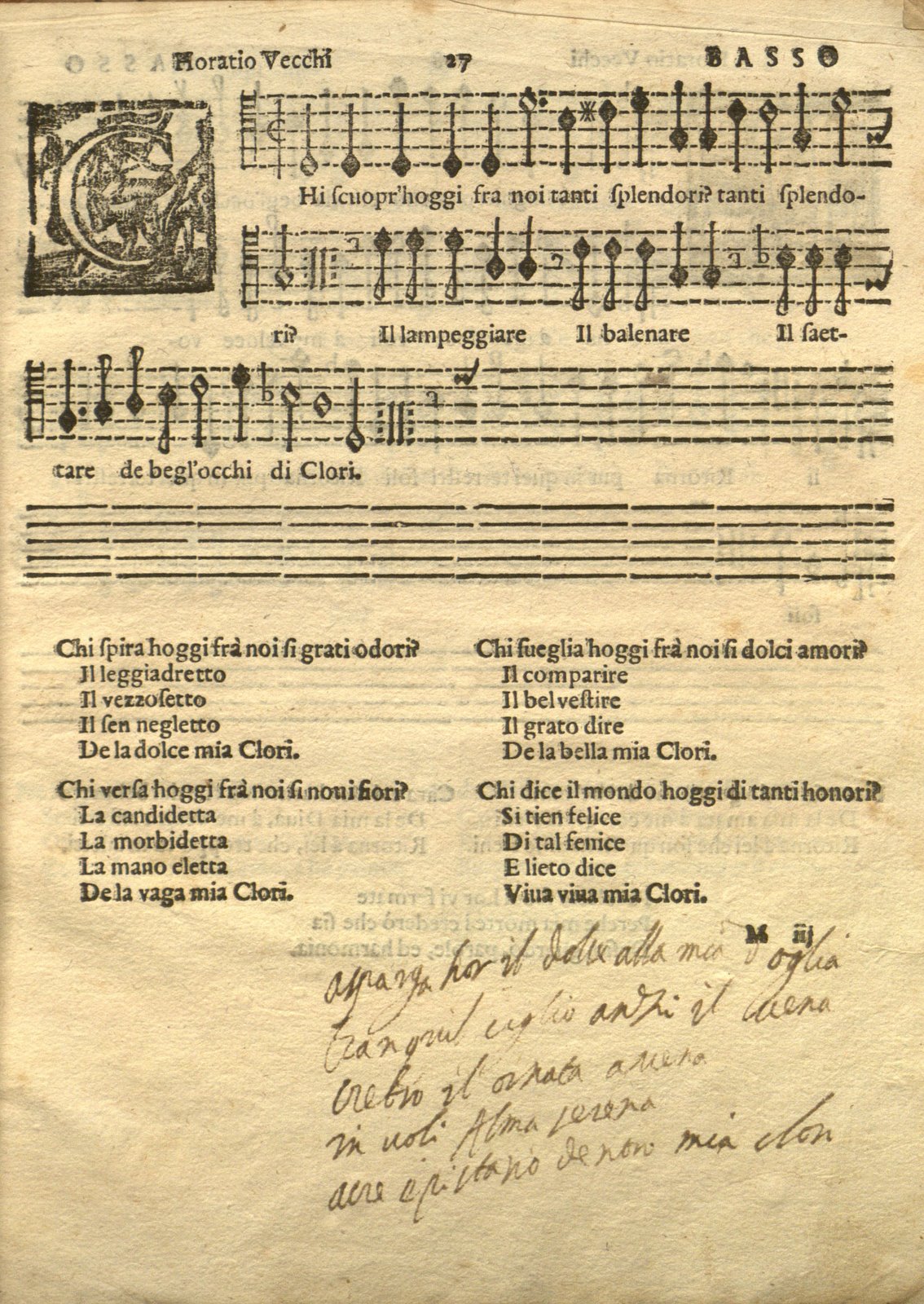

The bass partbook for the Canzonette à tre voci of Orazio Vecchi and his student Gemignano Capilupi contains the lowest part for 34 light and amorous trios. The canzonetta was a short, strophic song which, in Vecchi’s words, “did not bring great fatigue of mind.” In addition to the three vocal parts there would originally have been a fourth partbook containing tablature for a lutenist. Since the lute part doubles the voices, these pieces lent themselves to a variety of combinations from unaccompanied vocal trio to solo voice and lute. This kind of flexibility probably made for excellent sales for Angelo Gardano, who published this collection a year after the Piccioni.

Despite the felicity of this early partnership between master and student, undertaken when the younger musician was only 24 years old, Vecchi and Capilupi were not to remain friends. Capilupi’s jealousy over his master’s reputation eventually led him to cause Vecchi’s dismissal as maestro di capella at Modena Cathedral. When the older man died a year later, his rival succeeded to his posts both there and as musical director to the Duke of Modena. While Vecchi’s name is still known today, however, Capilupi’s fame has not weathered the passage of time.

Despite the felicity of this early partnership between master and student, undertaken when the younger musician was only 24 years old, Vecchi and Capilupi were not to remain friends. Capilupi’s jealousy over his master’s reputation eventually led him to cause Vecchi’s dismissal as maestro di capella at Modena Cathedral. When the older man died a year later, his rival succeeded to his posts both there and as musical director to the Duke of Modena. While Vecchi’s name is still known today, however, Capilupi’s fame has not weathered the passage of time.

The bass partbook in the Gorham Collection contains some contemporary annotations, including an additional verse to one of the songs, Chi scuopra oggi. Though the poetry does not fit the music as elegantly as the original text does, it gives us a compelling image of the man who once held and sang from this book. What caused him to add a verse to a song extolling the beauties and virtues of the fictional Clori? Who was his inspiration? Did he sing these words for her?

The Gardano printing house was founded in Venice in 1538 by Angelo’s father Antonio. Antonio (originally Antoine) had moved from France to Venice in the 1530s. He was a composer in his own right and was acquainted with many of the leading musicians working in Italy. One of these was the Netherlandish composer Adrian Willaert, who was born around 1490 and died in Italy in 1562. Willaert was one of the most influential composers and teachers of his time, numbering among his students the madrigalist Cipriano de Rore and theorist Gioseffo Zarlino (a print of whose influential Le istitutioni harmoniche also resides in the Gorham Collection).

The Gardano printing house was founded in Venice in 1538 by Angelo’s father Antonio. Antonio (originally Antoine) had moved from France to Venice in the 1530s. He was a composer in his own right and was acquainted with many of the leading musicians working in Italy. One of these was the Netherlandish composer Adrian Willaert, who was born around 1490 and died in Italy in 1562. Willaert was one of the most influential composers and teachers of his time, numbering among his students the madrigalist Cipriano de Rore and theorist Gioseffo Zarlino (a print of whose influential Le istitutioni harmoniche also resides in the Gorham Collection).

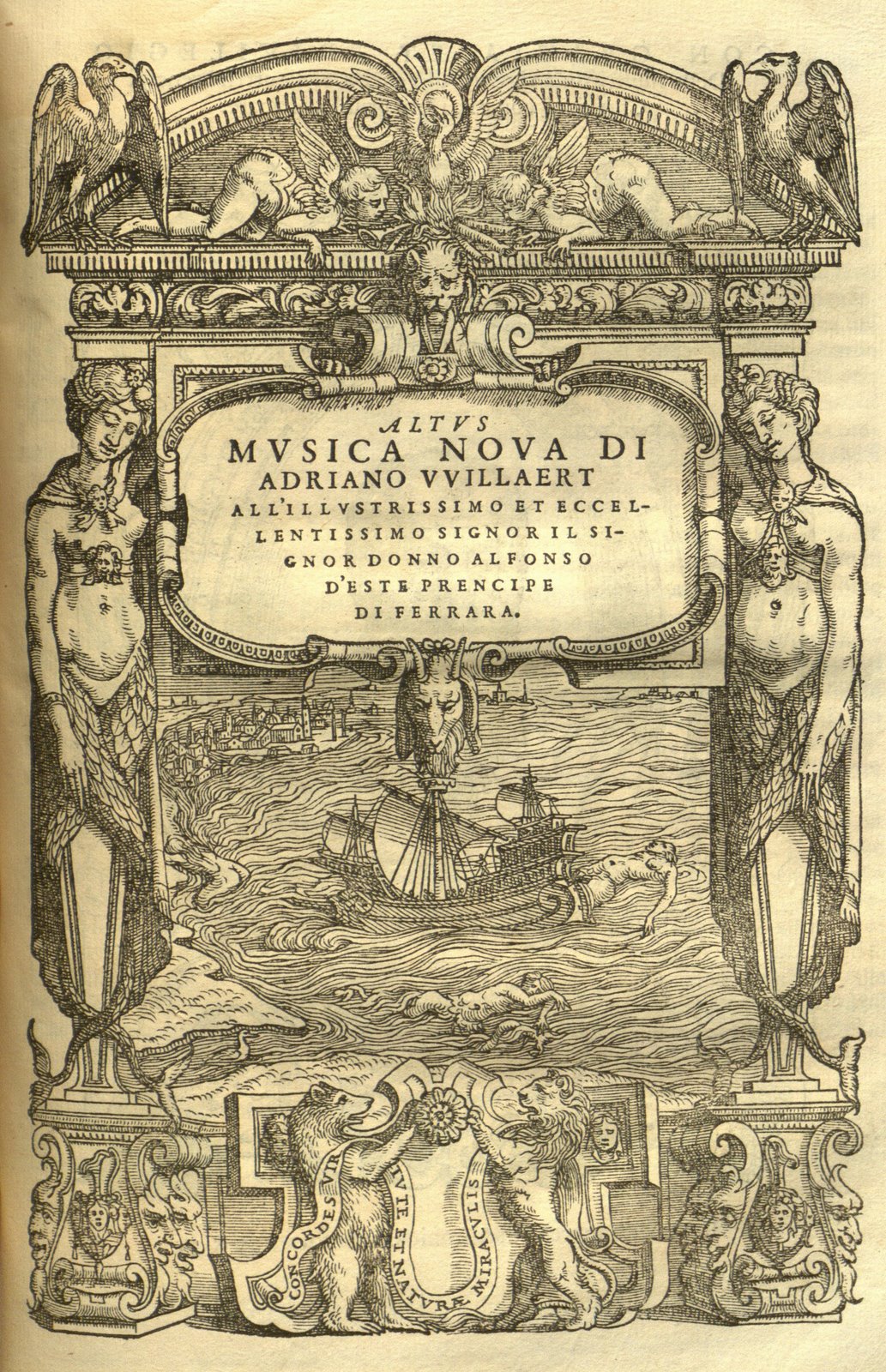

Although Willaert’s works had appeared in anthologies, it was the monumental collection Musica Nova that exemplified the significance of his work. The book was unusual in its time for containing both sacred and secular music. We can divine the influence of this publication from the fact that it is referred to in over a hundred extant documents from the period. Duke Alfonso d’Este subsidized the printing of this seminal work in 1559, for which Gardano devised a new format.  His previous publications had been oblong, but this one is an upright quarto. He also introduced a newly designed typeface and decorated initials for this publication. The clarity of the newly-cast type is striking when compared to earlier publications.

His previous publications had been oblong, but this one is an upright quarto. He also introduced a newly designed typeface and decorated initials for this publication. The clarity of the newly-cast type is striking when compared to earlier publications.

Gardano reused this deluxe design for a five-volume compilation of motets, the Novi Thesauri Musici, in 1568. The Gorham Collection contains a bound volume comprising the altus partbooks for the complete Novi Thesauri along with Willaert’s Musica Nova. Altogether this volume represents over 300 motets in addition to the 25 madrigals that make up the second half of Willaert’s book. Enhancing the collection are a number of handsome woodcuts.

In 1611 the Gardano firm passed to a third generation. Angelo’s daughter Diamante and son-in-law Bartolomeo Magni retained the illustrious name. Starting in that year, the printing house brought out six volumes of madrigals by Carlo Gesualdo.

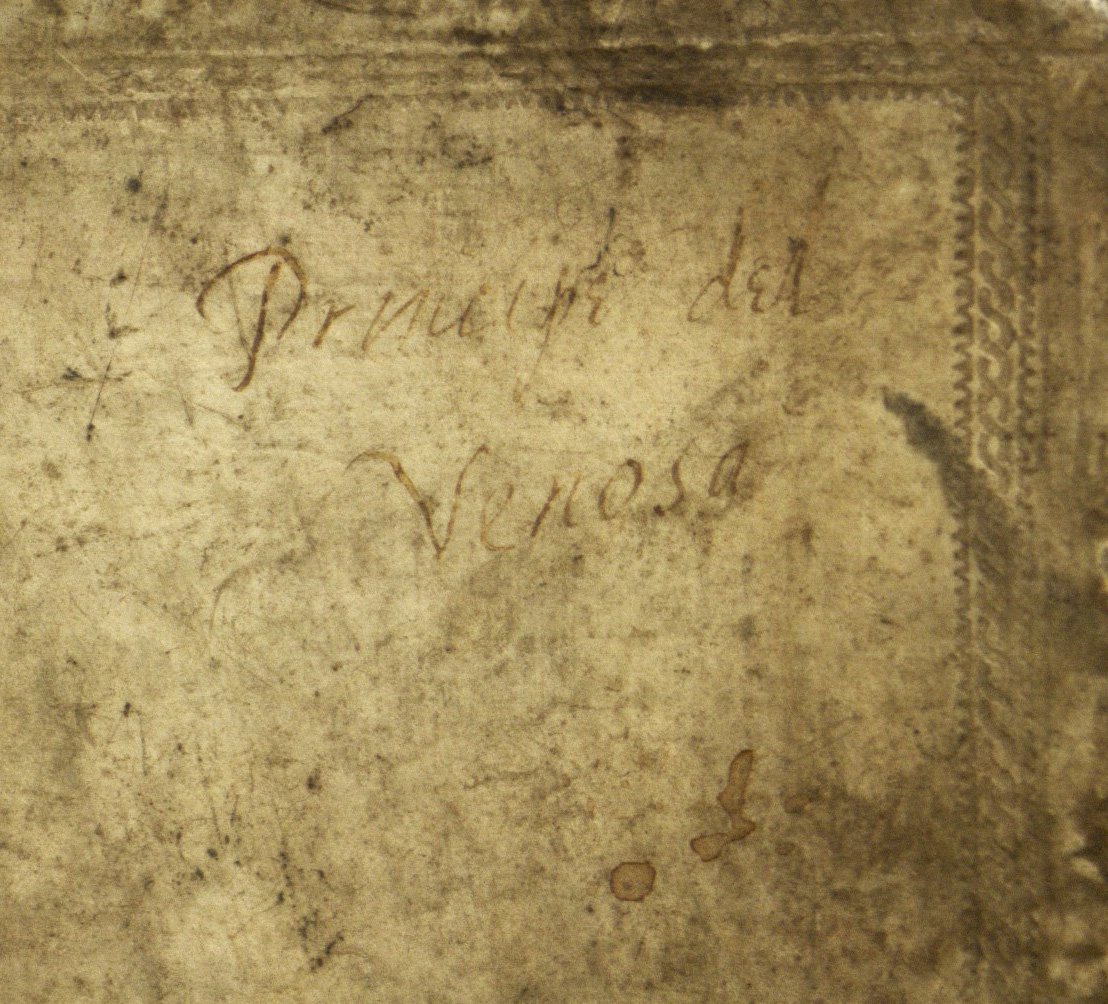

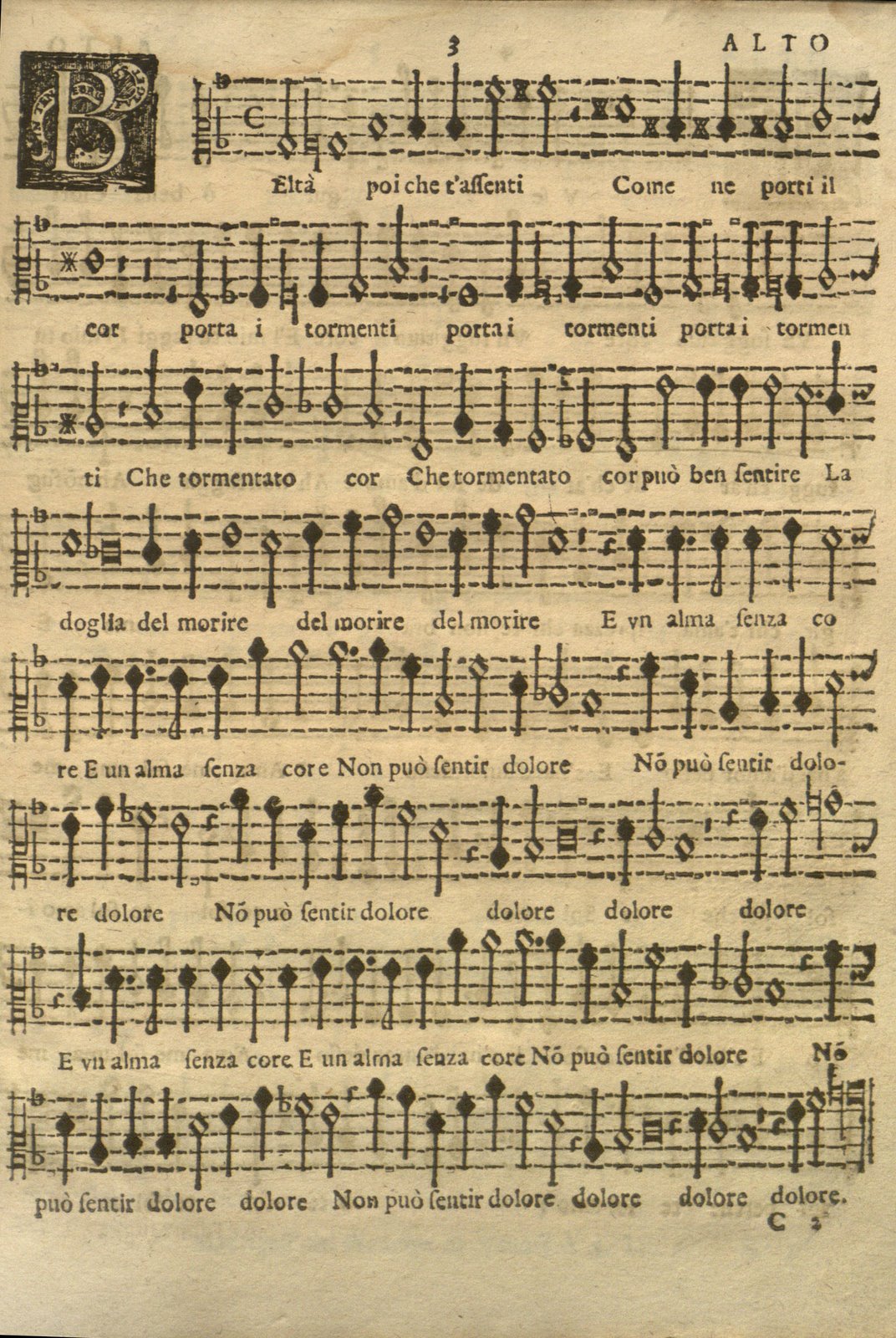

Those who know Gesualdo’s name today are likely to associate him with two things: chromaticism and murder. The Italian nobleman, who lived from 1561 to 1613, was early viewed as a dilettante, but earned the name of musician through his many publications, most notably the six volumes of five-part madrigals. His visibility increased after the assassination of his first wife and her lover, as did his “mad passion” for music, and this was further enhanced by his connections with the court of Ferrara after his marriage to Leonora d’Este.  As a prince, he was not constrained by economics to write music that would widely please, freeing him to push the boundaries of the madrigal with chromatic alterations and rhythmic surprises. The Gorham Collection boasts the only complete set of Altus partbooks to his madrigals in this country. Similar volumes that appear to have been their original partners are held in other U.S. libraries. The partbooks are bound together in contemporary vellum and inscribed with “Principe del Venosa” on the front cover. Below, a page from his sixth book of madrigals illustrates Gesualdo's chromatic lines.

As a prince, he was not constrained by economics to write music that would widely please, freeing him to push the boundaries of the madrigal with chromatic alterations and rhythmic surprises. The Gorham Collection boasts the only complete set of Altus partbooks to his madrigals in this country. Similar volumes that appear to have been their original partners are held in other U.S. libraries. The partbooks are bound together in contemporary vellum and inscribed with “Principe del Venosa” on the front cover. Below, a page from his sixth book of madrigals illustrates Gesualdo's chromatic lines.

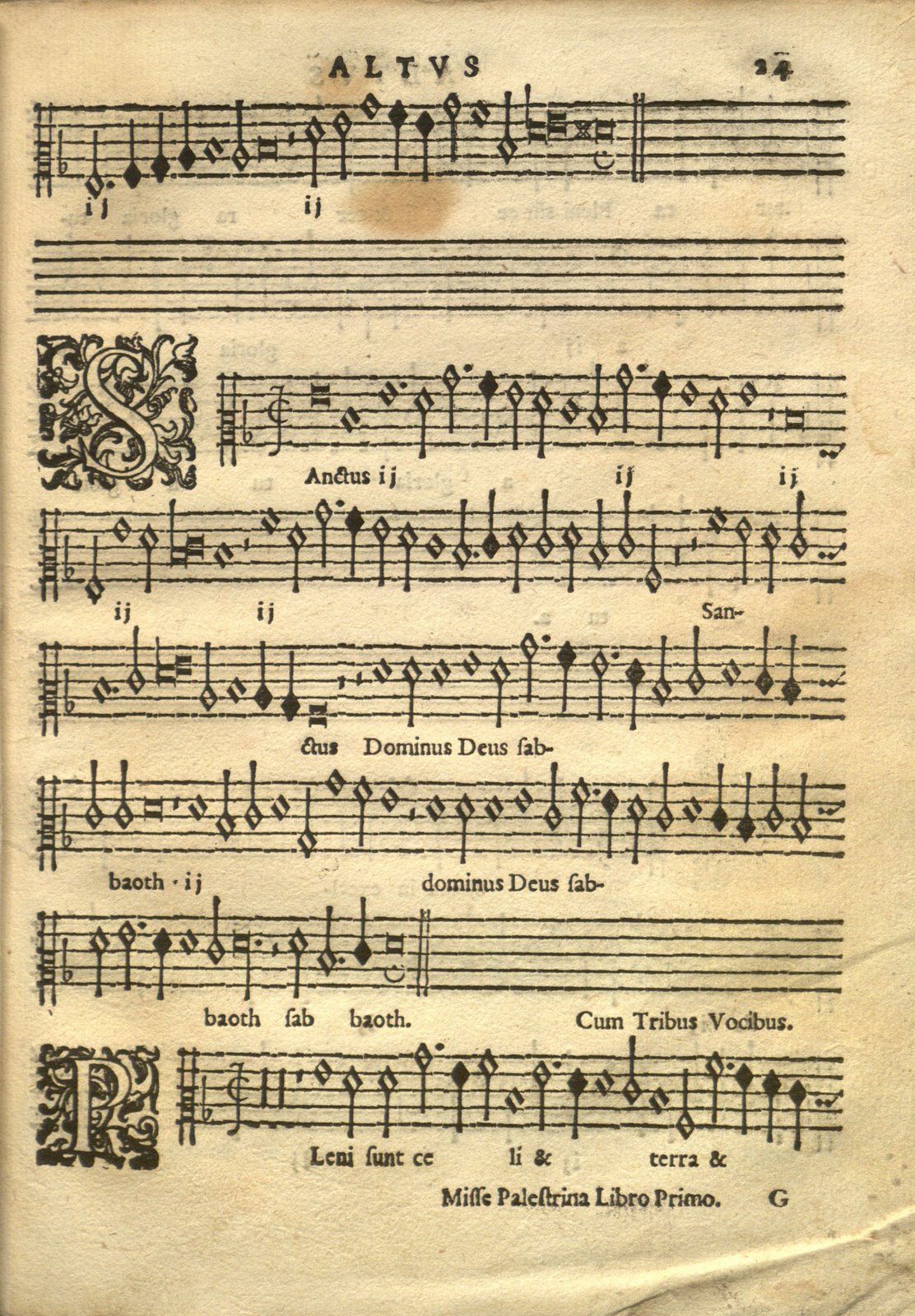

Allesandro Gardano, Angelo’s brother, worked side-by-side with him in Venice after their father’s death in 1569, but after six years he withdrew his assets from the firm and set up a separate shop. In the early 1580s he moved his press to Rome, where he focused on nonmusical editions, though he also published a number of sacred works by some of the leading Italian musicians of the day. Among these was the Roman composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, whose writing has for centuries been held up as the ideal of polyphonic style. In 1591, the year of his death, Allesandro brought out a new and expanded edition of Palestrina’s first book of masses, containing works for four, five and six voices. The alto partbook in the Gorham collection provides students with a remarkable opportunity to study these works at close hand.

Allesandro Gardano, Angelo’s brother, worked side-by-side with him in Venice after their father’s death in 1569, but after six years he withdrew his assets from the firm and set up a separate shop. In the early 1580s he moved his press to Rome, where he focused on nonmusical editions, though he also published a number of sacred works by some of the leading Italian musicians of the day. Among these was the Roman composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, whose writing has for centuries been held up as the ideal of polyphonic style. In 1591, the year of his death, Allesandro brought out a new and expanded edition of Palestrina’s first book of masses, containing works for four, five and six voices. The alto partbook in the Gorham collection provides students with a remarkable opportunity to study these works at close hand.

Like that of the Gardano family in Venice, the name Gerlach was associated with printing in Nuremberg. When Katherina Berg married Theodor Gerlach in 1565 she was already an experienced printer, as well as a widow twice over. Gerlach, who had probably been employed as a printer by her late husband, continued to run the company until his death in 1575, after which Katherina ran the firm on her own for another 17 years. Among their many publications they brought out a number of large collected editions of individual composers, among whom Orlando di Lasso figured prominently.

Like that of the Gardano family in Venice, the name Gerlach was associated with printing in Nuremberg. When Katherina Berg married Theodor Gerlach in 1565 she was already an experienced printer, as well as a widow twice over. Gerlach, who had probably been employed as a printer by her late husband, continued to run the company until his death in 1575, after which Katherina ran the firm on her own for another 17 years. Among their many publications they brought out a number of large collected editions of individual composers, among whom Orlando di Lasso figured prominently.

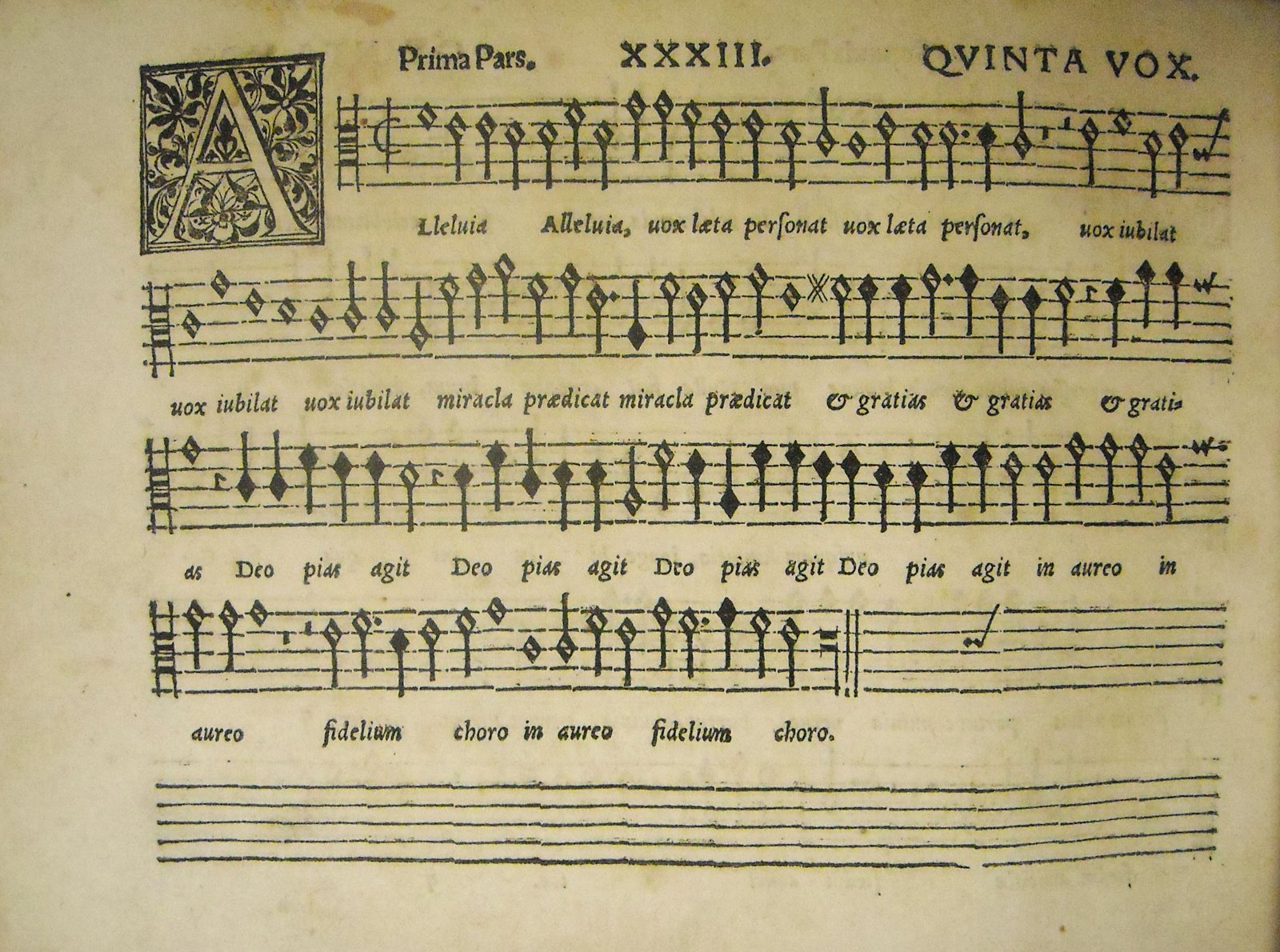

Lasso (1532–1594) was a prolific composer widely known and admired in his day. In 1568 he issued the first of many volumes of motets under the title Selectissimae cantiones… (“The choicest sacred songs, which are commonly called motets, partly altogether new, partly never before printed in Germany”). Brandeis owns a copy of the Quintus partbook of this work. Included in this book is a sacred contrafactum of a chanson first published nine years earlier; a piece that had begun life as a bawdy song was recycled as a joyful Alleluia.

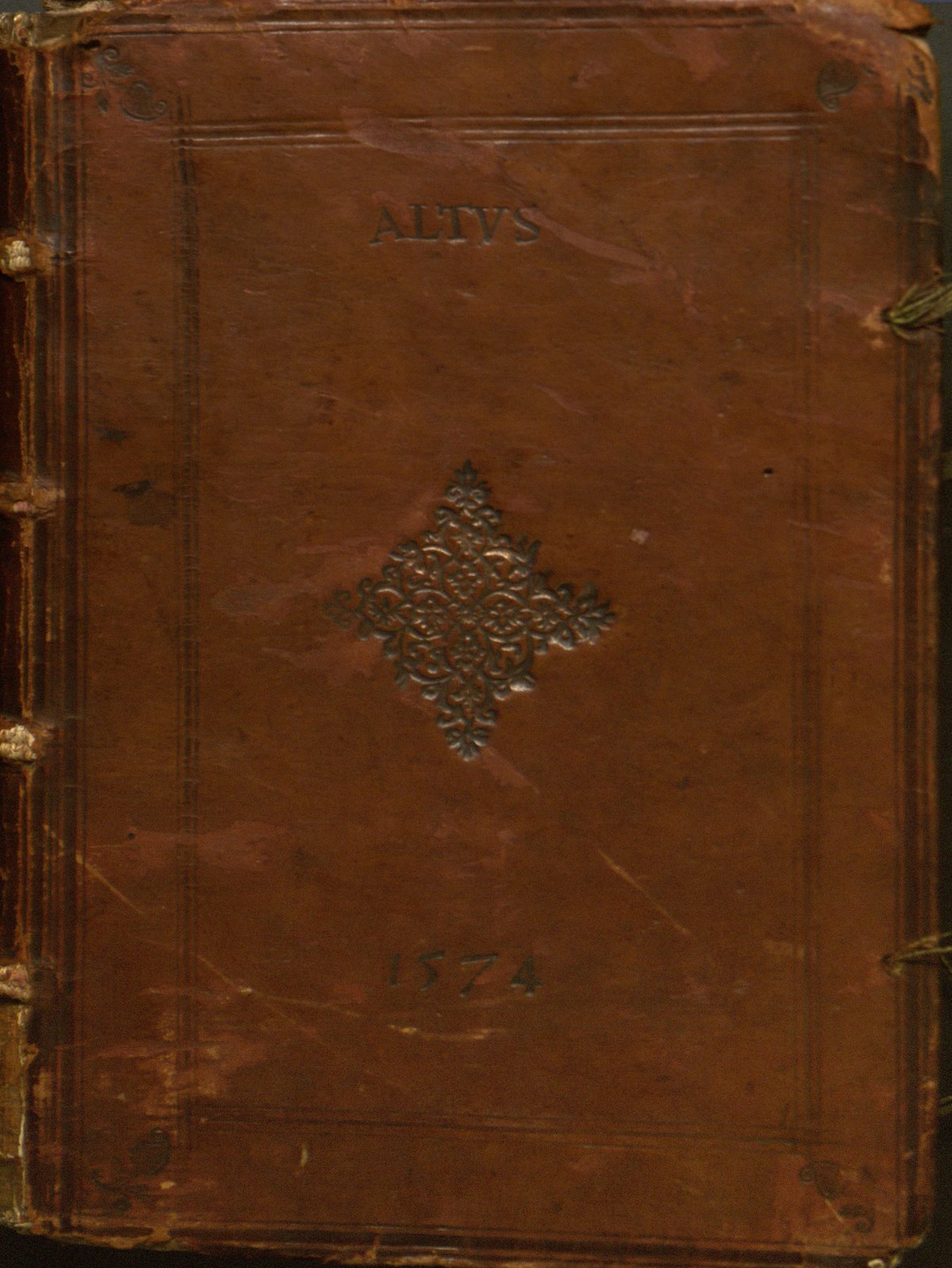

Nearly 20 years later this book was reissued in a revised and expanded form, under the title Altera pars Selectissimarum cantionum. The Gorham collection is fortunate to own a copy of the Altus partbook from this print, beautifully bound in leather with two other Lasso works. In combination with the Quintus partbook of the original print, Brandeis students can thus study two parts for some of the same pieces. Shown here are images of pages from these two prints showing the Alleluia, vox laeta with its original French title identifying its secular roots.

Nearly 20 years later this book was reissued in a revised and expanded form, under the title Altera pars Selectissimarum cantionum. The Gorham collection is fortunate to own a copy of the Altus partbook from this print, beautifully bound in leather with two other Lasso works. In combination with the Quintus partbook of the original print, Brandeis students can thus study two parts for some of the same pieces. Shown here are images of pages from these two prints showing the Alleluia, vox laeta with its original French title identifying its secular roots.

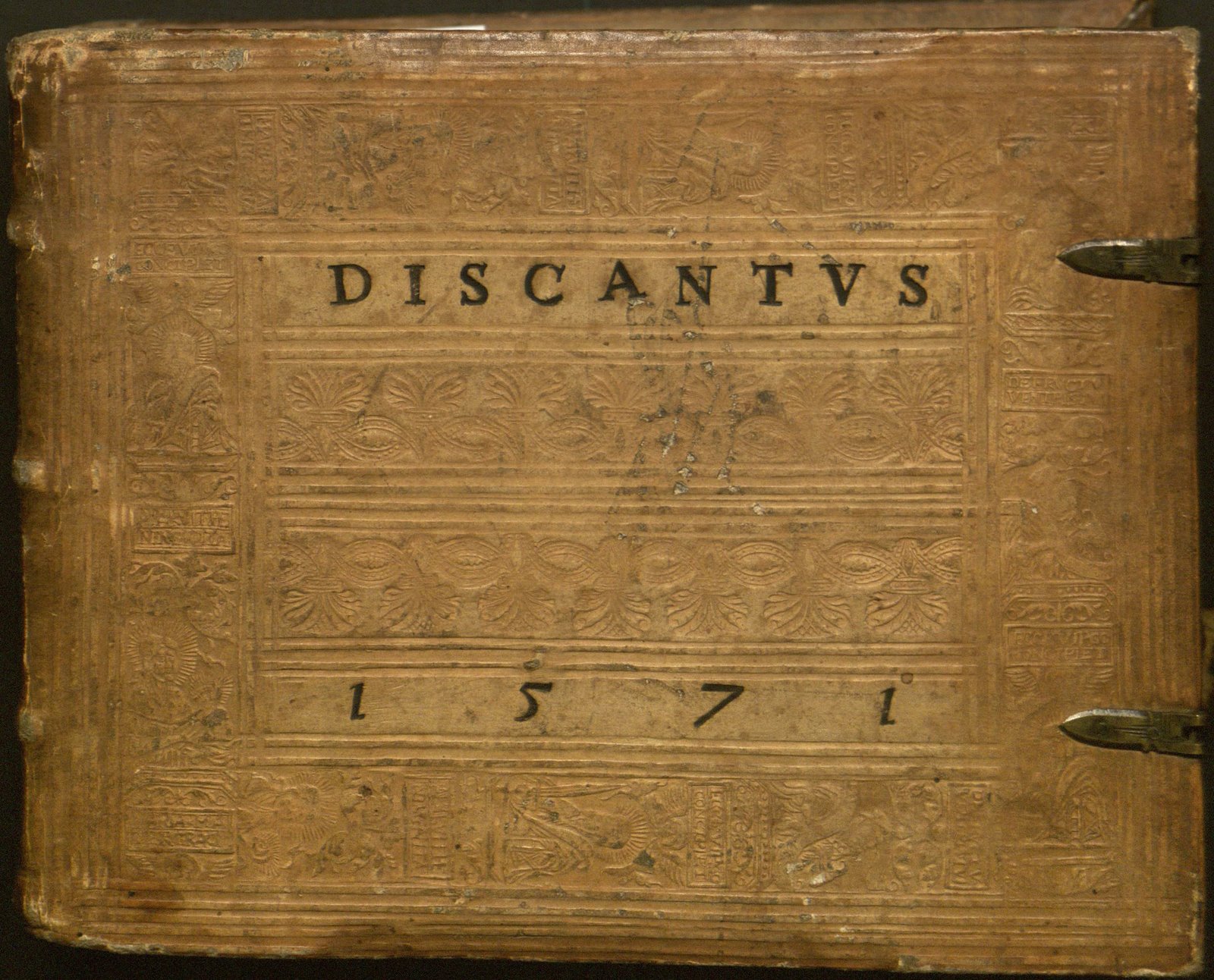

Probably the most compelling source of polyphonic music in the Gorham Collection is a hefty volume of Superius partbooks from the 1550s and ’60s, bound in tooled leather and stamped with the date of 1571. The remnants of brass closures are still attached to the cover, and tiny leather tabs are affixed to the first page of each book.

Probably the most compelling source of polyphonic music in the Gorham Collection is a hefty volume of Superius partbooks from the 1550s and ’60s, bound in tooled leather and stamped with the date of 1571. The remnants of brass closures are still attached to the cover, and tiny leather tabs are affixed to the first page of each book.

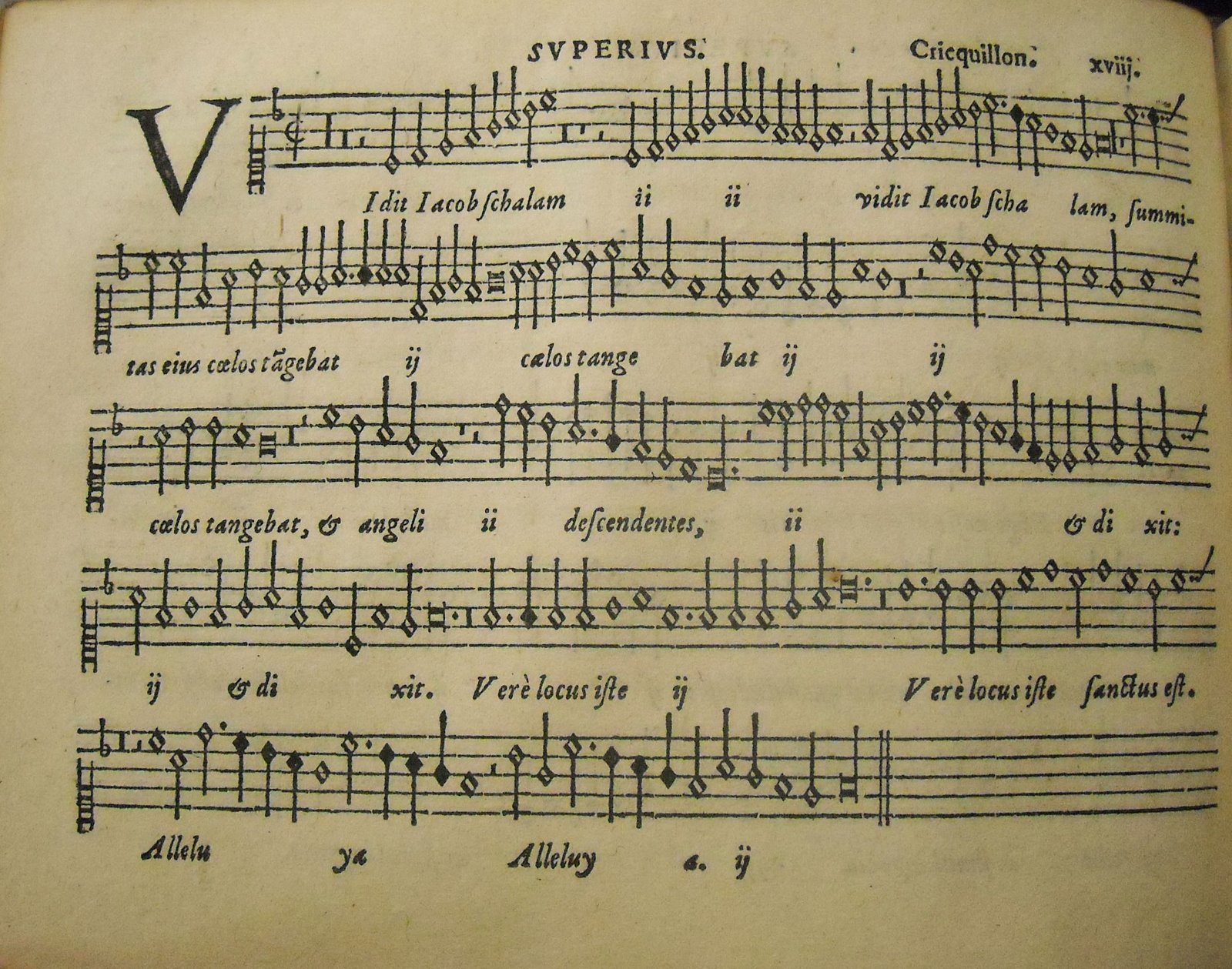

The first six partbooks in the volume are anthologies of motets published in Antwerp by Hubert Waelrant and Jan de Laet under the title Sacrarum Cantionum. Together they give a vivid snapshot of mid-century Franco-Flemish sacred music. Thomas Crecquillon, a member of the royal chapel for Emperor Charles V, died shortly after these anthologies were published. His work is well represented in these partbooks. Vidit Jacob scalam, pictured below, is a setting of the story of Jacob’s dream from Genesis 28: “Jacob saw a ladder, the top of which reached to heaven and angels descending on it.” The ladder (“scalam”) is illustrated by the opening scale, while the ascending and descending notes give a vivid picture of the angels going up and down. This kind of “word-painting” is most vivid in its original notation, where the diamond-headed notes are printed in close proximity, not interrupted by barlines or spaced according to their durations as they would be in a modern score.

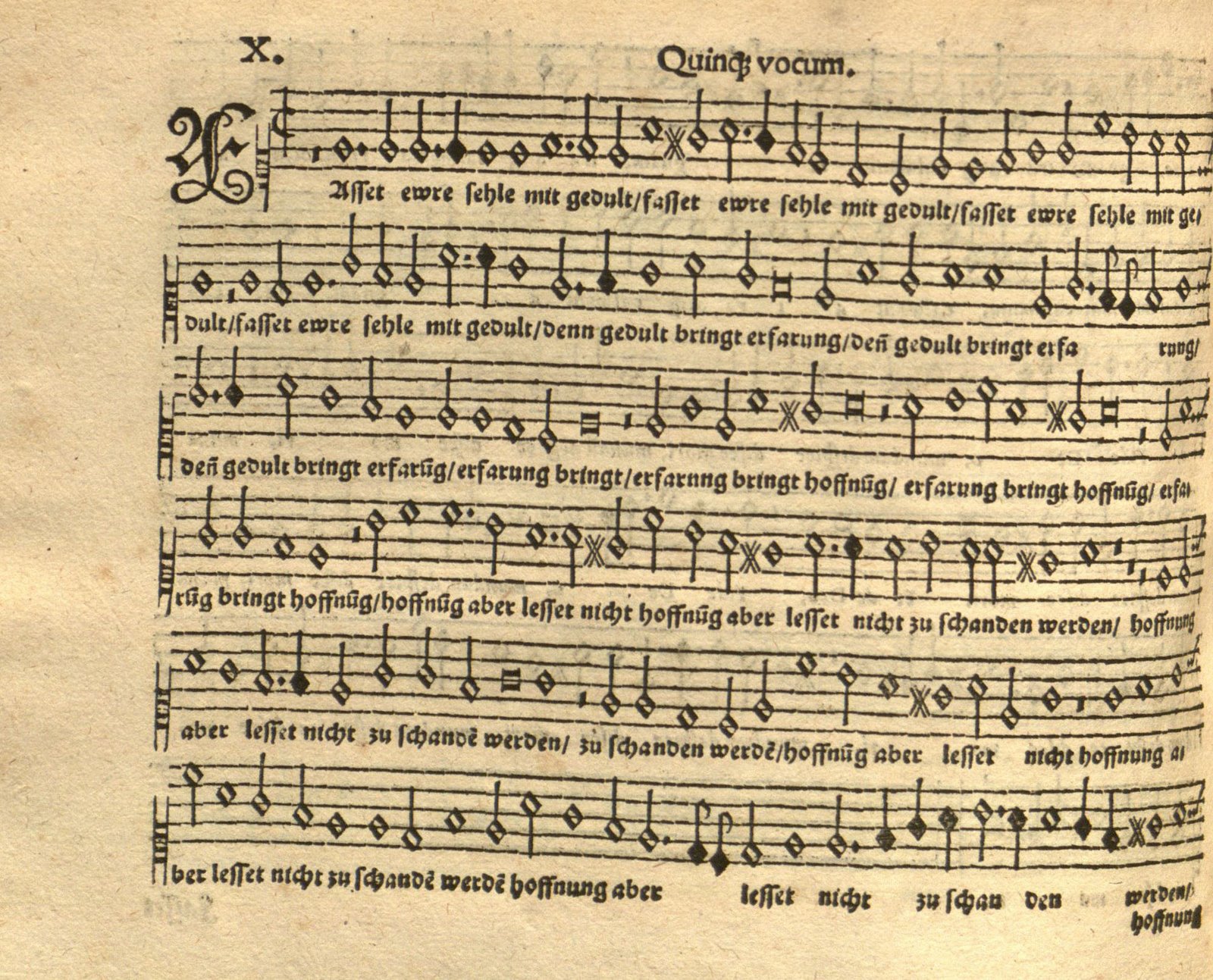

Bound among the 16 partbooks in this volume is one that has no title page; it has been identified as XIX Cantiones 4 & 5 vocum of Gallus Dressler, published in 1569. Brandeis senior Al Hoberman spent the fall 2008 semester researching this composer, whose work has yet to be brought out in a modern edition. Working from a microfilm of a complete set of partbooks, Hoberman has reconstructed one of the motets, Fasset eure seele mit gedult, pictured below.

Bound among the 16 partbooks in this volume is one that has no title page; it has been identified as XIX Cantiones 4 & 5 vocum of Gallus Dressler, published in 1569. Brandeis senior Al Hoberman spent the fall 2008 semester researching this composer, whose work has yet to be brought out in a modern edition. Working from a microfilm of a complete set of partbooks, Hoberman has reconstructed one of the motets, Fasset eure seele mit gedult, pictured below.

Most of the motets in this collection are on Latin texts, but three of them are in German. Dressler was a Philippist—a follower of a liberal sect that splintered from the Lutherans—who taught and wrote extensively about music theory and the expressive setting of text. His humanist leanings are demonstrated in his choice of a biblical text that focuses on personal responsibility.

In 1569 Clemens Stephani, a contentious poet, editor and bookseller from what is now the Czech Republic, published in Nuremberg a collection of fifteen settings of Psalm 128 for four to six voices under the title of Beati Omnes. The list of composers whose works are included ranges from some of the most well-known of the day to others who were already considered old-fashioned, and includes some so obscure that they appear in no other publication. The idea of collecting settings of the same text by many composers was uncommon and may have reflected Stephani’s Protestant zeal for education and moral uplift that is reflected in his literary publications. He was unable to hold any position for long because of his “poisonous, blasphemous tongue” and died penniless in 1592.

In 1569 Clemens Stephani, a contentious poet, editor and bookseller from what is now the Czech Republic, published in Nuremberg a collection of fifteen settings of Psalm 128 for four to six voices under the title of Beati Omnes. The list of composers whose works are included ranges from some of the most well-known of the day to others who were already considered old-fashioned, and includes some so obscure that they appear in no other publication. The idea of collecting settings of the same text by many composers was uncommon and may have reflected Stephani’s Protestant zeal for education and moral uplift that is reflected in his literary publications. He was unable to hold any position for long because of his “poisonous, blasphemous tongue” and died penniless in 1592.

This unusual collection is found just before the untitled Dressler partbook midway through this volume.

The works in this collection range from books by some of the most prominent composers of the day to some of the most obscure. Surprisingly, two different copies of Giaches de Wert's first volume of motets also appear here. One of these was printed in 1569, and the other—tucked in towards the end—is from the original 1566 printing. The appearance of two printings of the same book within this large collection of prints is quite curious. It lends to the impression that this splendid volume was compiled by a collector who was more interested in amassing an impressive anthology than in examining its contents in depth. One imagines a man with more money than he could keep track of sending his agent out to buy up all the latest sacred music. Perhaps the bookseller saw this as an opportunity to offload a few items from his remaindered list. This volume, richly bound and clasped and shelved alongside its companion partbooks, must have been a part of a handsome private library, or perhaps it was compiled for the court. One wonders how many of the hundreds upon hundreds of pieces it contains were ever read through in the household for which it was obtained. How many hands has it passed through since, and when did it become separated from its companions?

The partbooks in the Gorham collection represent a rich source of repertoire in its original notation. In the autumn of 2008 the Brandeis Early Music Ensemble undertook a project to perform representative works from each of these volumes. They again performed some of these works in a presentation at the Rapaporte Treasure Hall in the Goldfarb Library on Friday, January 16, 2009, where audience members had the opportunity to see some of these books in person and read from facsimiles of the original notation. Sarah Mead, director of the Early Music Ensemble, provided comments on the works to be performed.