Trimalchio (or The Great Gatsby)

June 14, 2017

Description by Katie Graff, MA student in Classical Studies and Archives and Special Collections assistant.

In June 1922, F. Scott Fitzgerald sent a brief letter to his editor: “When I send on this last bunch of stories I may start my novel…Its locale will be the middle west and New York of 1885 I think. It will concern less superlative beauties than I run to usually + will be centered on a smaller period of time. It will have a catholic element. I am not quite sure whether I’m ready to start it quite yet or not. I’ll write next week + tell you more definite plans.” Though perhaps not recognizable as such at this early stage of development, this is the first mention by Fitzgerald of his plan for the novel that would become his magnum opus, “The Great Gatsby.”

In June 1922, F. Scott Fitzgerald sent a brief letter to his editor: “When I send on this last bunch of stories I may start my novel…Its locale will be the middle west and New York of 1885 I think. It will concern less superlative beauties than I run to usually + will be centered on a smaller period of time. It will have a catholic element. I am not quite sure whether I’m ready to start it quite yet or not. I’ll write next week + tell you more definite plans.” Though perhaps not recognizable as such at this early stage of development, this is the first mention by Fitzgerald of his plan for the novel that would become his magnum opus, “The Great Gatsby.”

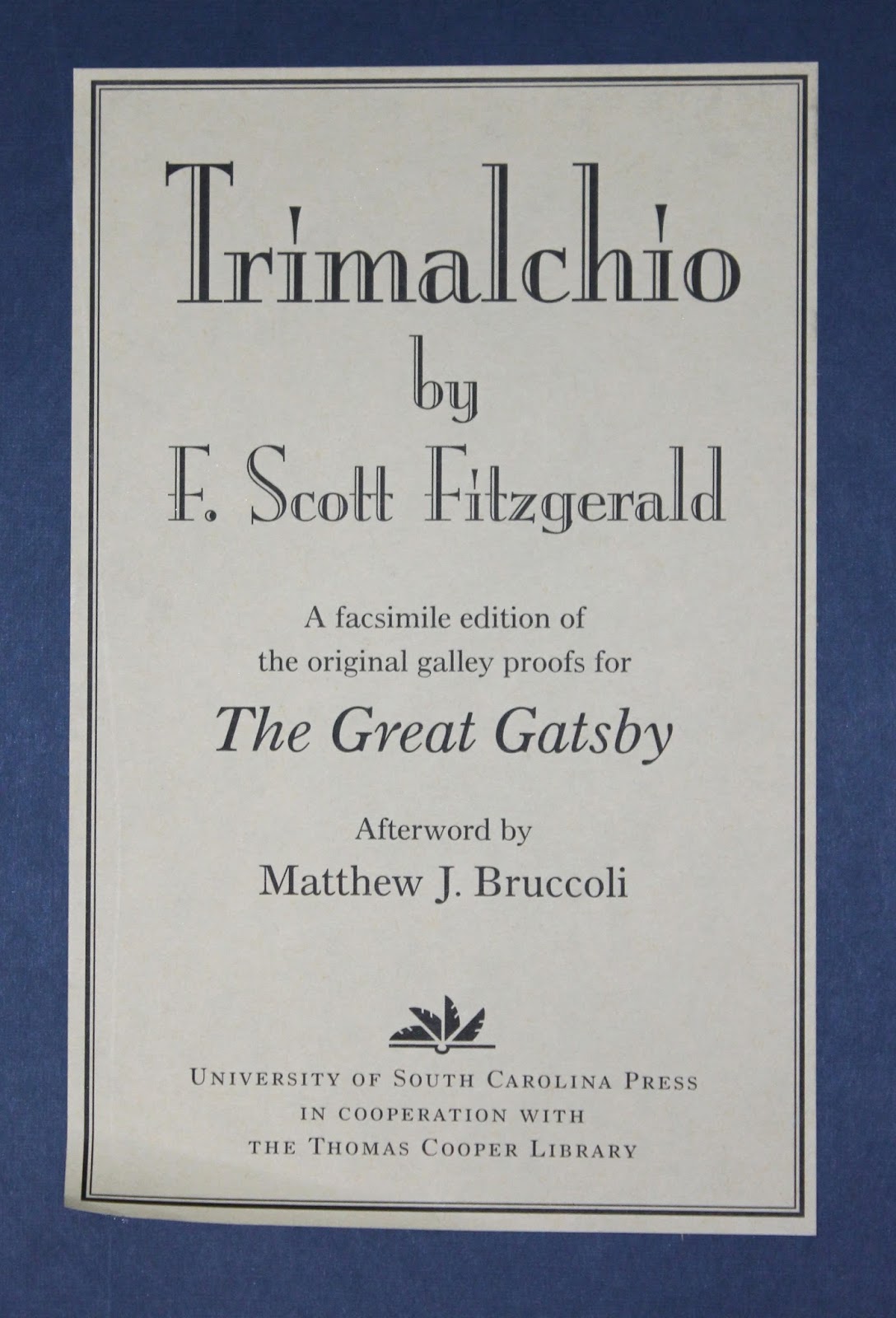

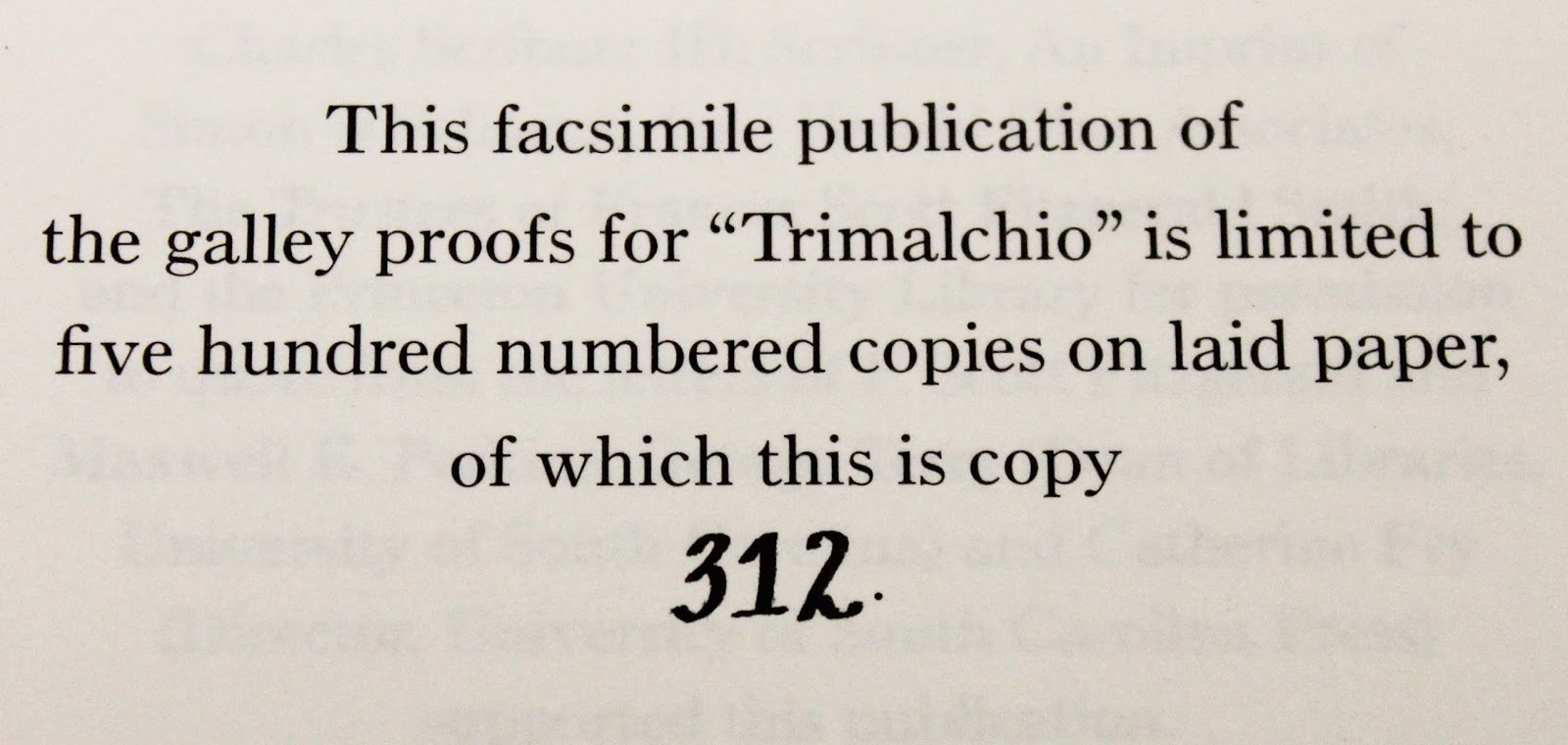

In the canon of American Literature, “The Great Gatsby” often holds the honor of being considered the front contender for the title of the “Great American Novel.” Interestingly enough, however, this praise took decades to earn, and was something Fitzgerald himself sought tirelessly and unsuccessfully throughout the last two decades of his life. Among the rare book holdings of Brandeis’ Special Collections is a numbered facsimile of the first galley proofs of this book — known at the moment of its printing as “Trimalchio.” Though the originals sold at auction in 1971, in reality they are priceless because they comprise the only extant pre-publication version of the novel.

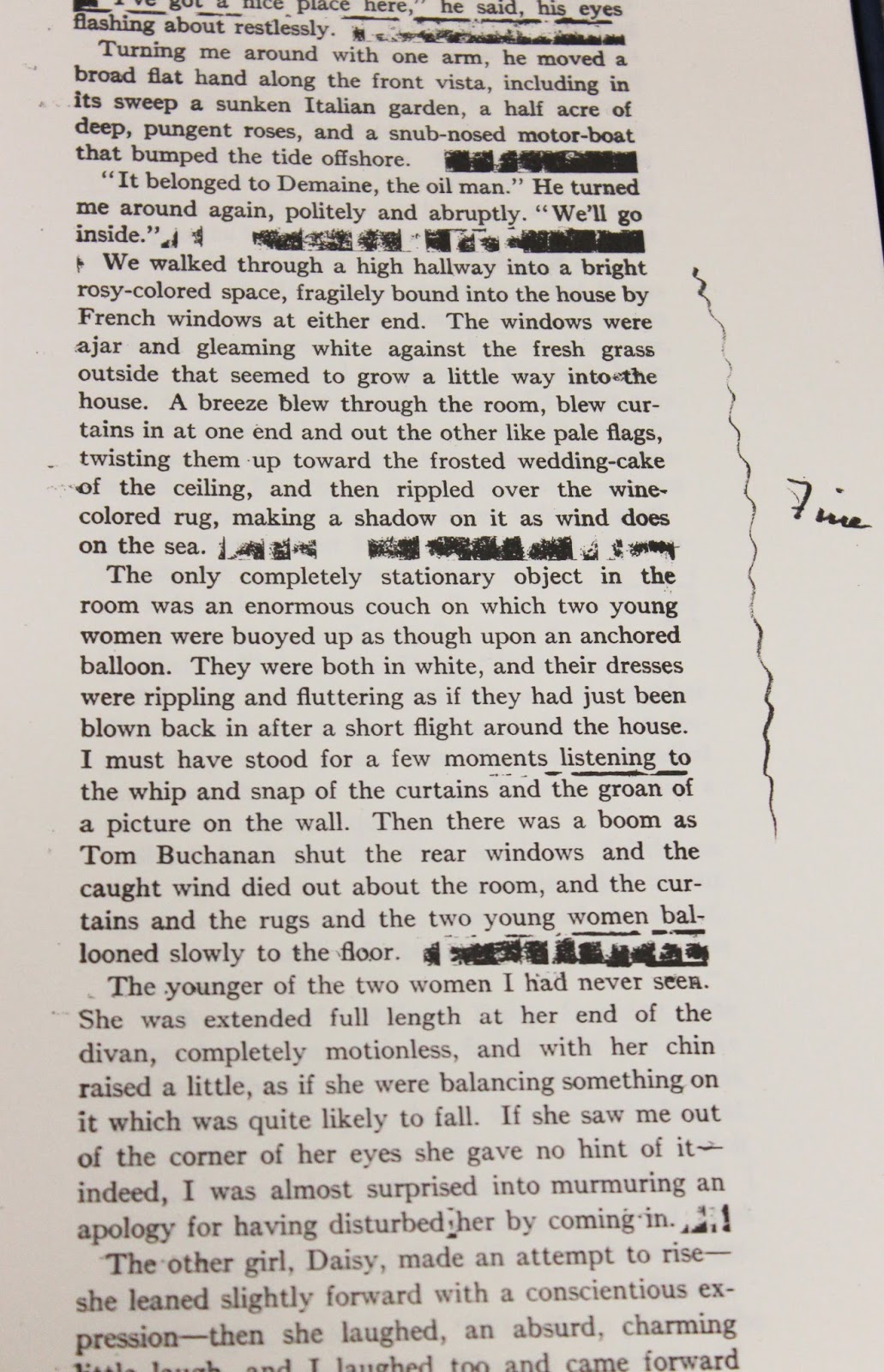

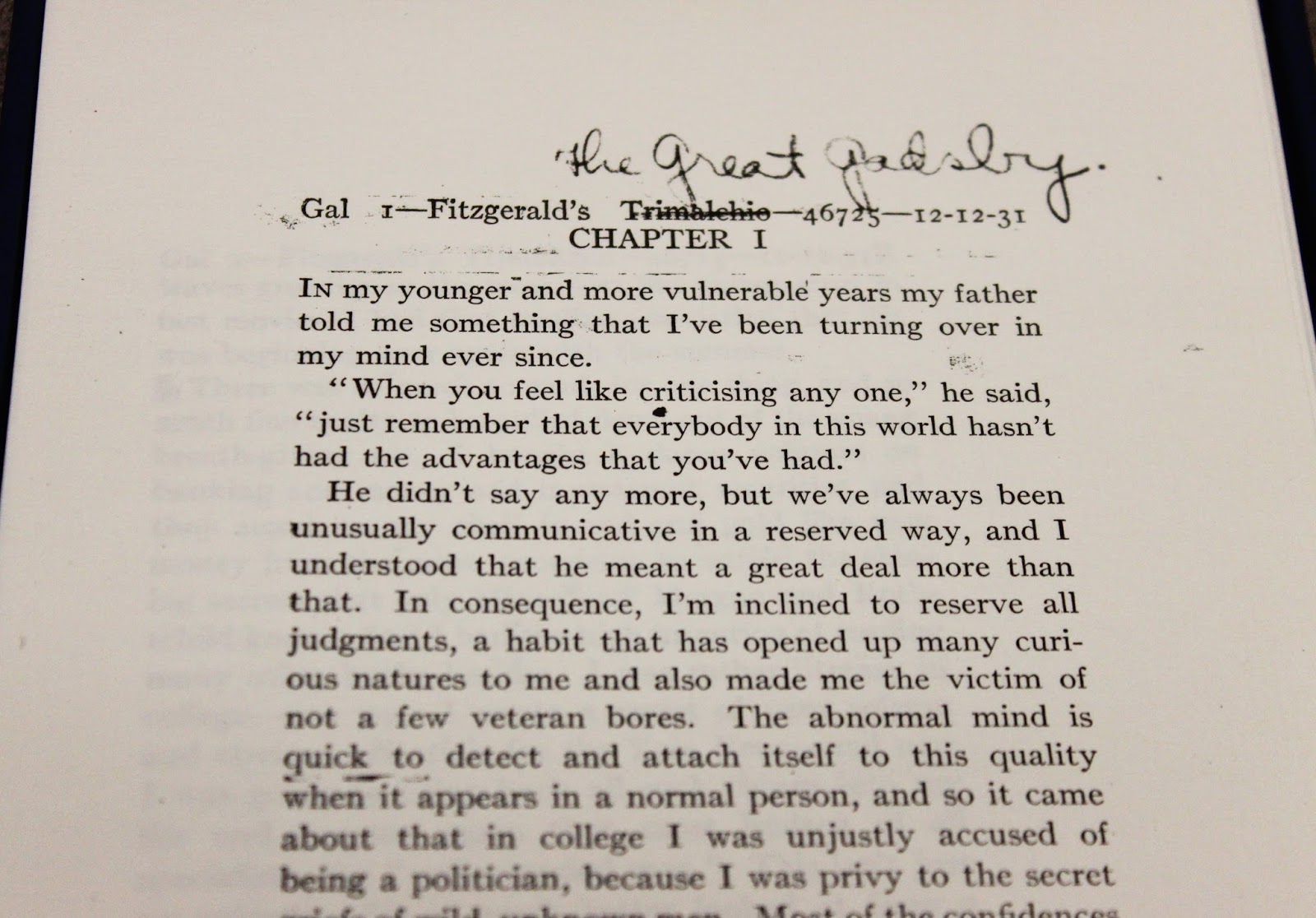

Sadly, aside from a hastily scribbled-over title change, there are no editorial notes on the pages. However, the layout and characterizations of “Trimalchio” differ greatly from the final novel, and therefore provide insight into one of the great, if not the greatest, American novels. This version of the book, from its early title to its preliminary layout (which differs quite a bit from the now-beloved published version) offers researchers a special view into Fitzgerald’s original intentions for the novel, and reflects his well-documented anxieties regarding its development and publication.

At its heart, the novel is about the rebound effects of the American Dream; a cynical, if not satirical, portrait of America at the height of the roaring 20s. The protagonist, Jay Gatsby, is a self-made millionaire fighting to earn a place not only beside his debutante love Daisy Buchanan, but also alongside the upper-crust members of early 20th-century high society.

Though few critics would dare to call “The Great Gatsby” directly autobiographical, it is clear that it is perhaps one of the most meaningful to the author in terms of direct personal engagement, and was intended to be the culmination of semi-autobiographical themes he had explored in numerous previously published short stories and novels. The novel that “Trimalchio” became seems to mirror several of Fitzgerald’s struggles: to prove himself worthy of a wealthy woman, his lifelong effort to make something of himself and his anxieties of failing to accomplish his dreams. Similarly, the “Trimalchio” proof seems to reflect the particular tensions and pressures Fitzgerald faced at the time of its writing: though he began the novel in the summer of 1923, he set it aside following the failure of his play “The Vegetable” in order to pay off his debts by quickly publishing a number of short stories. Furthermore, the relationship of Daisy and Gatsby can be said to parallel the path of Fitzgerald’s own marriage. In fact, snippets of Daisy’s dialogue are directly from Zelda. Daisy’s oft-quoted hope that her daughter would be a “beautiful little fool — that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world” were words spoken by Zelda in an anesthesia haze after giving birth to their only child — a daughter.

Though few critics would dare to call “The Great Gatsby” directly autobiographical, it is clear that it is perhaps one of the most meaningful to the author in terms of direct personal engagement, and was intended to be the culmination of semi-autobiographical themes he had explored in numerous previously published short stories and novels. The novel that “Trimalchio” became seems to mirror several of Fitzgerald’s struggles: to prove himself worthy of a wealthy woman, his lifelong effort to make something of himself and his anxieties of failing to accomplish his dreams. Similarly, the “Trimalchio” proof seems to reflect the particular tensions and pressures Fitzgerald faced at the time of its writing: though he began the novel in the summer of 1923, he set it aside following the failure of his play “The Vegetable” in order to pay off his debts by quickly publishing a number of short stories. Furthermore, the relationship of Daisy and Gatsby can be said to parallel the path of Fitzgerald’s own marriage. In fact, snippets of Daisy’s dialogue are directly from Zelda. Daisy’s oft-quoted hope that her daughter would be a “beautiful little fool — that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world” were words spoken by Zelda in an anesthesia haze after giving birth to their only child — a daughter.

The most obvious and interesting difference between this proof and the final published work is the title. Fitzgerald cycled through several titles, including “Under the Red, White and Blue,” “Among the Ash-Heaps and Millionaires,” “Gold-Hatted Gatsby,” and “Trimalchio in West Egg.” Often, he would set aside one title at the encouragement of friends and peers, just to return to it again later. It is important to note, however, that Fitzgerald seems to have favored some iteration on “Trimalchio” in most drafts, and with good reason.

“Trimalchio,” known well to Classics scholars, is a character from the work of Latin satirist Petronius. This text, “Satyricon,” follows the fictional journey of a traveling rhetoric teacher and his companion Giton. “Satyricon” is considered to be one of the earliest works of deliberate fiction, and is studied as a chronicle of attitudes and perceptions toward lower-class citizens of the Roman Empire. One of the work’s most famous sections describes the mishaps of a gaudy and crude party thrown by a former slave named Trimalchio, a man who embodies the “new money” archetype in every way. Trimalchio is boorish and rude, brightly gilded but lacking manners, substance or even polity. Every aspect of his new existence is carefully chosen to reinforce his new status, and suggest an air of desperation to prove his place in proper society. His full name — Gaius Pompeius Trimalchio Maecenatianus — implies a link to both Pompey and Maecenas, famous figures in the late years of the Roman Republic, and while no one seems to be sure precisely how he made his vast and sudden wealth, they know at the very least it was in dishonest or distasteful ways.

Trimalchio is introduced as the host of a party in his villa, where he provides his guests a lavish but debauched experience. The revelers, largely fellow freedmen, marvel at his luxurious home and possessions and enjoy rich food, drink and entertainment, all the while descending into increased drunkenness. Throughout the celebration Trimalchio attempts to impress his guests with symbols of his status and ubiquitous wealth, including repeated references to his lavish plans for his tomb. Indeed, the party culminates when Trimalchio’s obnoxious showiness prompts him to act out his own mock funeral for the amusement of his guests and his own reassurance.

Trimalchio is introduced as the host of a party in his villa, where he provides his guests a lavish but debauched experience. The revelers, largely fellow freedmen, marvel at his luxurious home and possessions and enjoy rich food, drink and entertainment, all the while descending into increased drunkenness. Throughout the celebration Trimalchio attempts to impress his guests with symbols of his status and ubiquitous wealth, including repeated references to his lavish plans for his tomb. Indeed, the party culminates when Trimalchio’s obnoxious showiness prompts him to act out his own mock funeral for the amusement of his guests and his own reassurance.

The connection of title character Jay Gatsby to Trimalchio is clear. Gatsby is a former nobody who can suddenly claim great wealth by uncertain means, a figure of gossip and speculation trusted by no one, whose wealth is taken advantage of by everyone. Much like Trimalchio’s miscalculated fete, and despite, or perhaps because of, his best intentions, Gatsby’s parties do not represent wealth and status so much as corruption and excess. The nouveau riche and corrupted old money alike consume these parties decadently, partaking in the free-flowing drink, food and jazz music. Their excessiveness suggests an underlying crudeness lacking in those securely born into wealth and status — a theme that underwrites the main tension of the novel.

Fitzgerald seems to have greatly enjoyed the “Trimalchio” title, and felt that it represented best the ideology and paradoxical “innocent corruption” the character of Gatsby was meant to embody. Unfortunately, the “Trimalchio”-based titles were ultimately forced into rejection by his publishers based on their belief that the American public could neither pronounce the name nor understand the reference.

Among the other changes from the “Trimalchio” proof to the published “Gatsby” is a less complete failure of Gatsby’s dream: his relationship with his father appears more friendly and communicative, and his associate Meyer Wolfsheim appears to have a genuine fondness for Gatsby and regret over his death, rather than the character serving as a mere shadow figure who used Gatsby as a tool and scavenged his estate for profit. As well, his argument with his rival Tom Buchanan is more even and less awkward for Gatsby, and the chain of events leading to the pivotal death of Tom’s mistress Myrtle Wilson is far more ambiguous in terms of who was responsible for the accident. In general, careful readers will find subtle shifts in the dialogue and plot which provide new perspectives and insight into well-tread events and familiar characters.

Sadly, even after settling on a title and plot, “The Great Gatsby” proved to be a nagging anxiety for Fitzgerald and was accompanied by unrest in both his personal and professional life. Fitzgerald’s moderate literary success, for example, proved a stress in his marriage. His wife Zelda, from a wealthy and influential family, had married him on condition that he could support her and her lifestyle. On a writer’s income, this proved near impossible. Much of the positive reviews of Gatsby at the time of its publication came from personal communications from writer and critics friends to whom he had he sent copies, seeking legitimate praise and approval. Yet, even with their encouraging remarks, he never seemed quite satisfied. At the time of its publication, the novel was deemed an overwrought mess, irrelevant, and gaudy. Many critics panned it, and it was considered a mediocre commercial success at best. The value of the novel was proven only after it could be read objectively in separation from the age which produced it, by which point the Great Depression and the Second World War had sobered America and the country felt a paradoxical coexistence of nostalgia and disdain for Gatsby’s era.

Sadly, even after settling on a title and plot, “The Great Gatsby” proved to be a nagging anxiety for Fitzgerald and was accompanied by unrest in both his personal and professional life. Fitzgerald’s moderate literary success, for example, proved a stress in his marriage. His wife Zelda, from a wealthy and influential family, had married him on condition that he could support her and her lifestyle. On a writer’s income, this proved near impossible. Much of the positive reviews of Gatsby at the time of its publication came from personal communications from writer and critics friends to whom he had he sent copies, seeking legitimate praise and approval. Yet, even with their encouraging remarks, he never seemed quite satisfied. At the time of its publication, the novel was deemed an overwrought mess, irrelevant, and gaudy. Many critics panned it, and it was considered a mediocre commercial success at best. The value of the novel was proven only after it could be read objectively in separation from the age which produced it, by which point the Great Depression and the Second World War had sobered America and the country felt a paradoxical coexistence of nostalgia and disdain for Gatsby’s era.

Within the past two years, Cambridge University Press has released an edited copy of this proof, titled “Trimalchio: An Early Version of the Great Gatsby”. Though this mass-produced version is far easier on the eyes to read, Fitzgerald fans, biographers and literary critics and scholars might find that the opportunity to see the text as Fitzgerald and his publishers would have read it, crooked, with ink block smudges and typos rampant, holds a unique charm. In addition, this limited release contains an afterword by literary scholar and professor, Matthew J. Bruccoli, which provides a wealth of insight into the creative process and agonies of writing “The Great Gatsby,” as well as the biographical events of Fitzgerald’s life and death which helped shaped the beloved novel as it is known today. Though Brandeis’ galley proofs are clean copy (they do not have any handwritten edits), they nonetheless contain interesting information and, when compared to the final form of the Gatsby so cherished today, lift the veil on the publishing and editorial process of a novel that has inspired generations of writers, filmmakers and dreamers.