A Few Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts at Brandeis

April 30, 2010

Description by Leah Lefkowitz, undergraduate student in history and English

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis houses several medieval manuscripts that depict beautiful examples of illumination. Four notable examples include an early-14th-century French breviary fragment; two Books of Hours, one the Italian Office of the Virgin from the 15th century, and one a 15th-century text from the Netherlands; and a 1485 copy of De Pictura (“On Painting”) written by Leon Battista Alberti between 1420 and 1430. Although these texts span more than a hundred years and several countries, they demonstrate striking similarities that indicate artistic patterns in the Middle Ages.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis houses several medieval manuscripts that depict beautiful examples of illumination. Four notable examples include an early-14th-century French breviary fragment; two Books of Hours, one the Italian Office of the Virgin from the 15th century, and one a 15th-century text from the Netherlands; and a 1485 copy of De Pictura (“On Painting”) written by Leon Battista Alberti between 1420 and 1430. Although these texts span more than a hundred years and several countries, they demonstrate striking similarities that indicate artistic patterns in the Middle Ages.

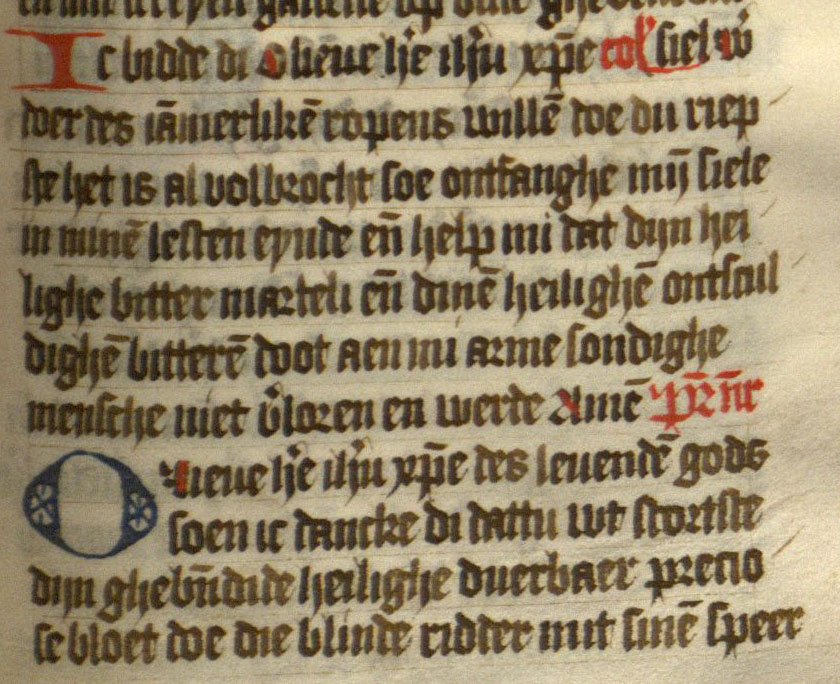

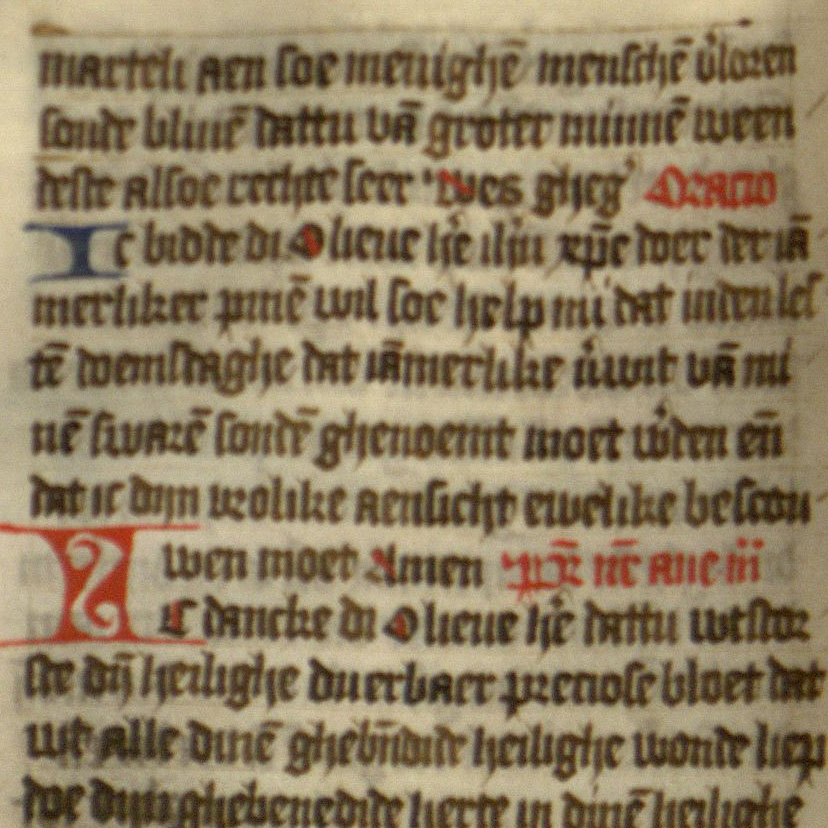

Illumination in these four texts can be divided into three categories: colored initials, ornately designed initials and miniature paintings. Colored initials appear in all four of the manuscripts described here. In these four texts, the two most frequently used colors for script are red and blue; scribes more commonly wrote in red ink, which may be because the composition of red ink allowed it to flow more easily than blue.[1] The illuminated letters in medieval manuscripts vary in size. Some are the same size as the surrounding black text, whereas others occupy an entire page. Size variation indicated hierarchical variation: the larger the letter, the more important the moment in the text.

For example, the two pages seen here, an initial O and an initial I, from Alberti’s De Pictura, depict colored letters that are only a little larger than one line or two lines of the regular text. The I and the O are not only slightly larger than the single-line, colored letters on the page; they also include decorations inside the letters. These differences help to divide the page into recognizable segments and thereby increase the legibility of a page that has no lowercase letters and no punctuation.

For example, the two pages seen here, an initial O and an initial I, from Alberti’s De Pictura, depict colored letters that are only a little larger than one line or two lines of the regular text. The I and the O are not only slightly larger than the single-line, colored letters on the page; they also include decorations inside the letters. These differences help to divide the page into recognizable segments and thereby increase the legibility of a page that has no lowercase letters and no punctuation.

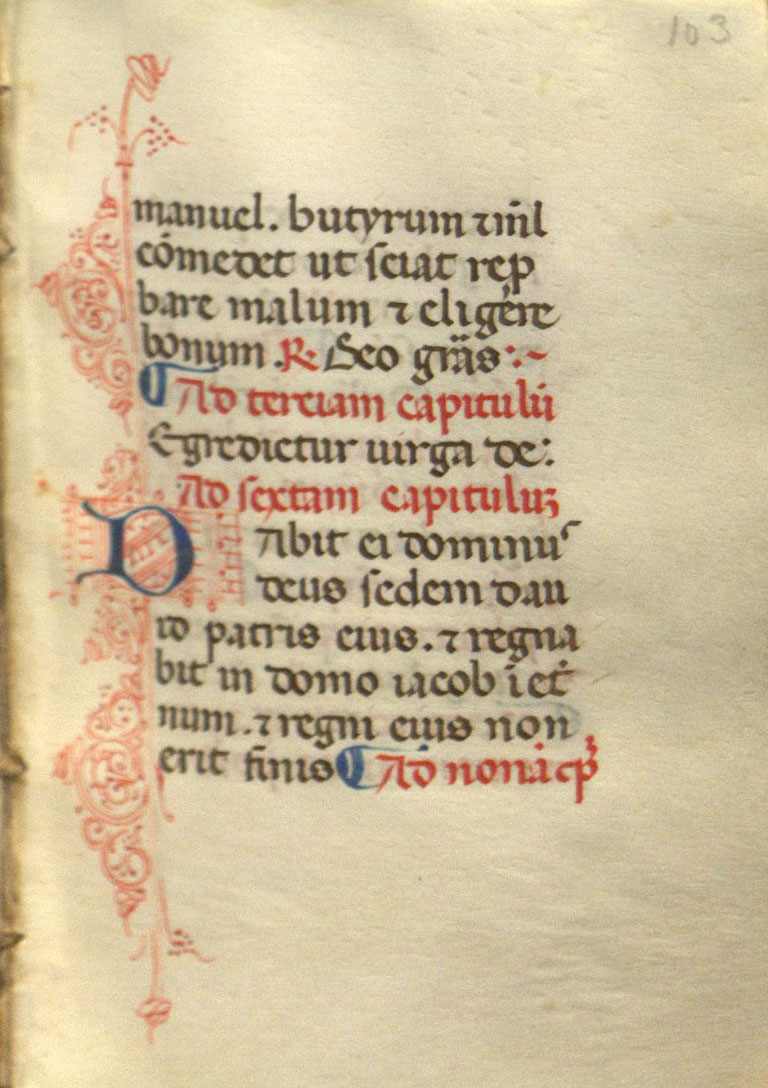

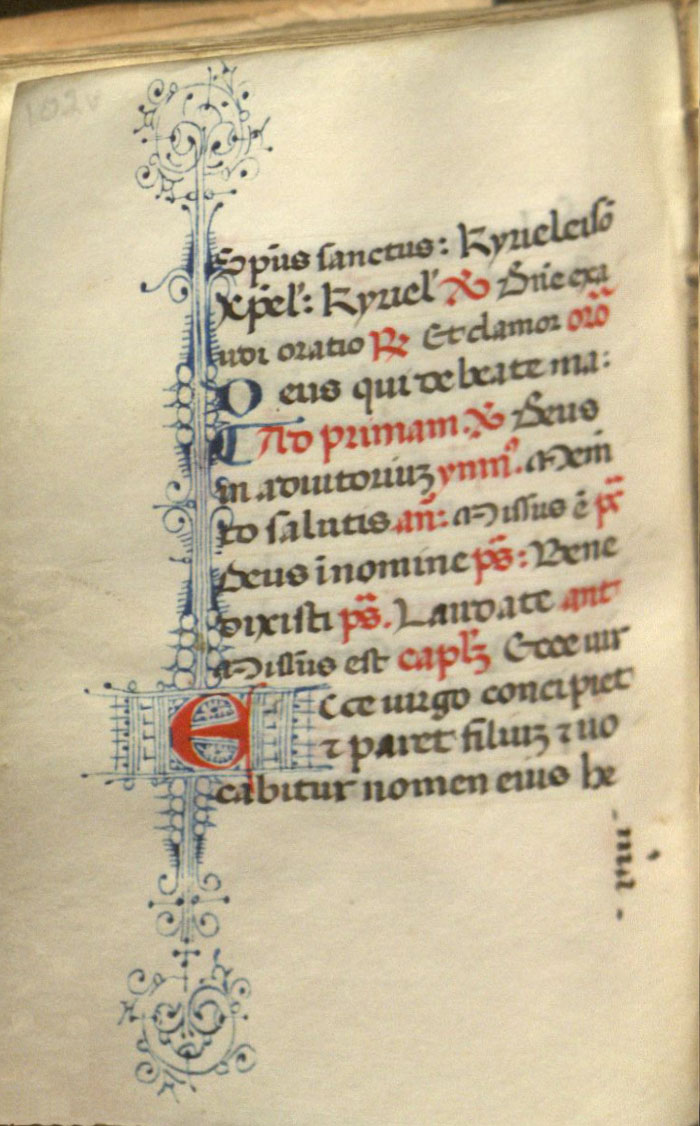

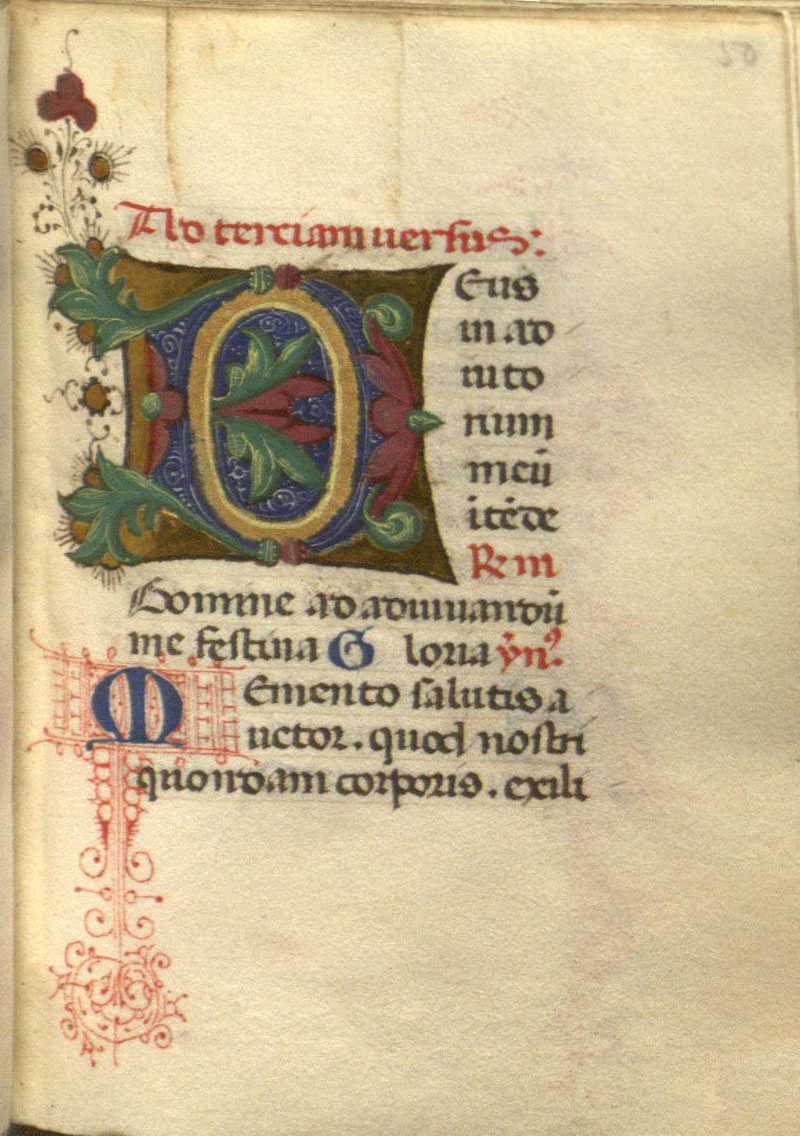

Slightly more elaborate letters than the I and the O are surrounded by linear borders. For example, swirling linear designs, called “penwork flourishing,” encompass this D and this E from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours. Designs such as these sometimes fully surround the page, and sometimes they decorate only part of the page, as these do.

Slightly more elaborate letters than the I and the O are surrounded by linear borders. For example, swirling linear designs, called “penwork flourishing,” encompass this D and this E from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours. Designs such as these sometimes fully surround the page, and sometimes they decorate only part of the page, as these do.

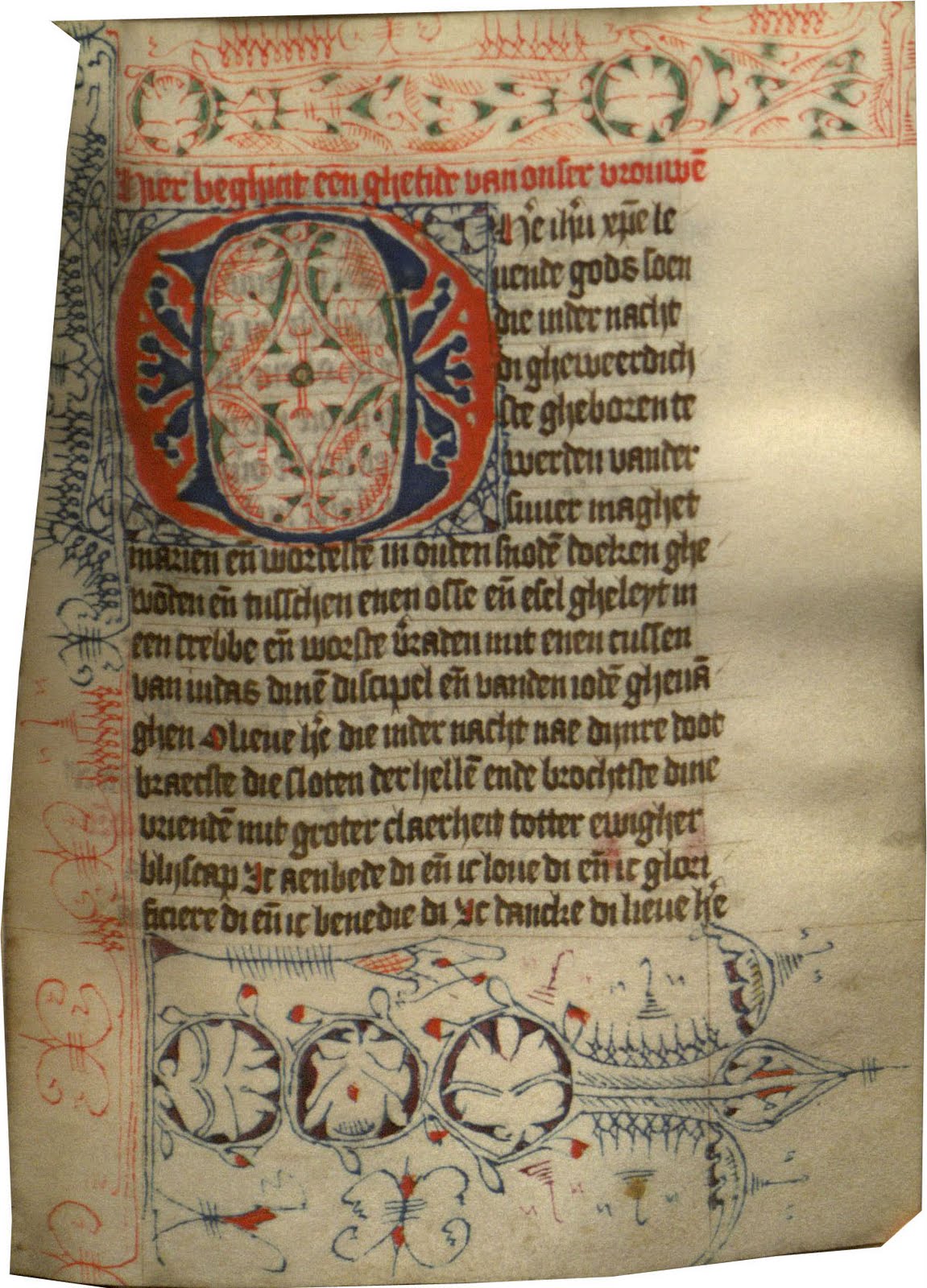

In contrast to the previous two colored borders, this third one, from De Pictura, which depicts a large seven-line O, also includes the color green. Because the letter is larger and more elaborately decorated than the previous D and E, viewers can assume that it marks an important moment within the text. This type of letter is called a puzzle-initial because of the blank space between the red and the blue colors, which creates a puzzle-like appearance. Another difference between the first D and E borders, from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours, and the second O border, from De Pictura, is that the latter includes recognizable objects, such as leaves and flowers.

In contrast to the previous two colored borders, this third one, from De Pictura, which depicts a large seven-line O, also includes the color green. Because the letter is larger and more elaborately decorated than the previous D and E, viewers can assume that it marks an important moment within the text. This type of letter is called a puzzle-initial because of the blank space between the red and the blue colors, which creates a puzzle-like appearance. Another difference between the first D and E borders, from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours, and the second O border, from De Pictura, is that the latter includes recognizable objects, such as leaves and flowers.

A second example of a heavily illuminated initial is this letter D from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours. The borders are drawn in a style different from the others, but it too spans seven lines of text and depicts swirling designs. The flowers on this initial are easier to recognize as flowers. Also, the leaves include subtle shading, increasing the realism of the object. Another interesting feature of this beflowered D is the faintly visible penciled lines between the lines of text. A scribe drew these lines before writing the text not only to keep the text evenly spaced, but also to ensure that the illuminated letters grew at regular intervals. For example, the M is exactly twice as big as the surrounding text.

A second example of a heavily illuminated initial is this letter D from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours. The borders are drawn in a style different from the others, but it too spans seven lines of text and depicts swirling designs. The flowers on this initial are easier to recognize as flowers. Also, the leaves include subtle shading, increasing the realism of the object. Another interesting feature of this beflowered D is the faintly visible penciled lines between the lines of text. A scribe drew these lines before writing the text not only to keep the text evenly spaced, but also to ensure that the illuminated letters grew at regular intervals. For example, the M is exactly twice as big as the surrounding text.

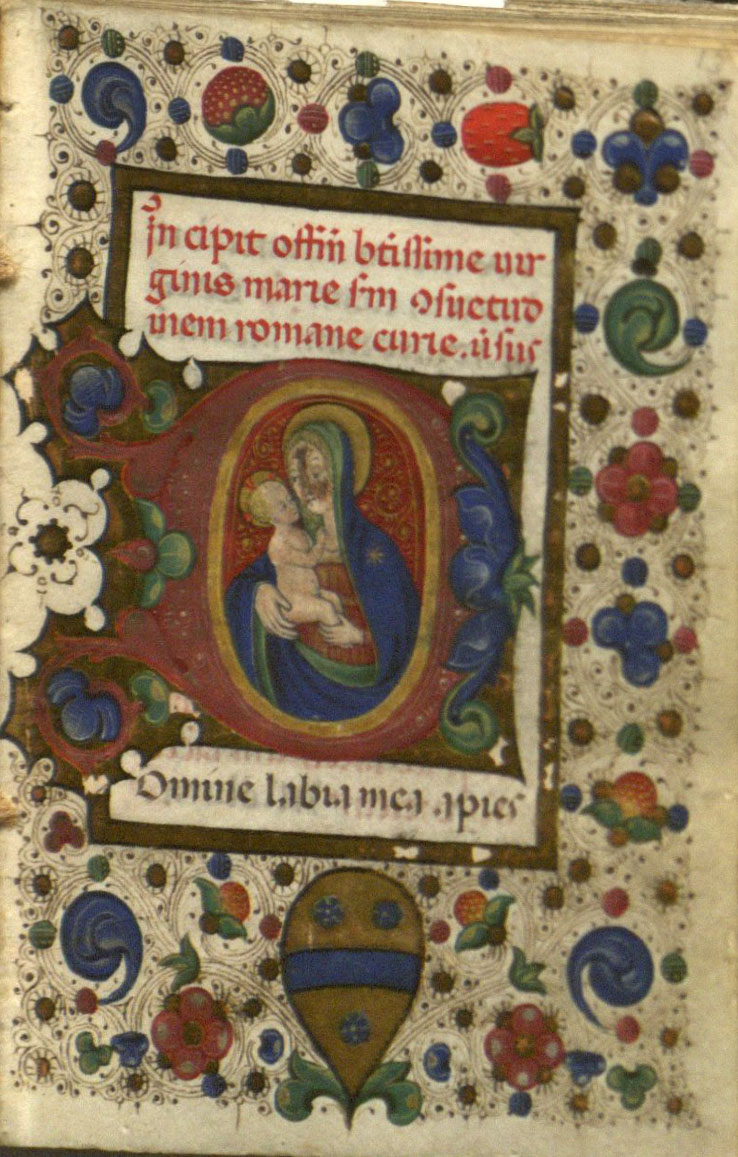

The most ornately illuminated initials seen here are inhabited initials, which depict human figures or animal figures inside the letter. Although only a few inches high, one example, from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours, depicts the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus inside a letter D. A border of swirling lines, flowers and fruit surrounds the miniature painting.

The most ornately illuminated initials seen here are inhabited initials, which depict human figures or animal figures inside the letter. Although only a few inches high, one example, from the 15th-century Italian Book of Hours, depicts the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus inside a letter D. A border of swirling lines, flowers and fruit surrounds the miniature painting.

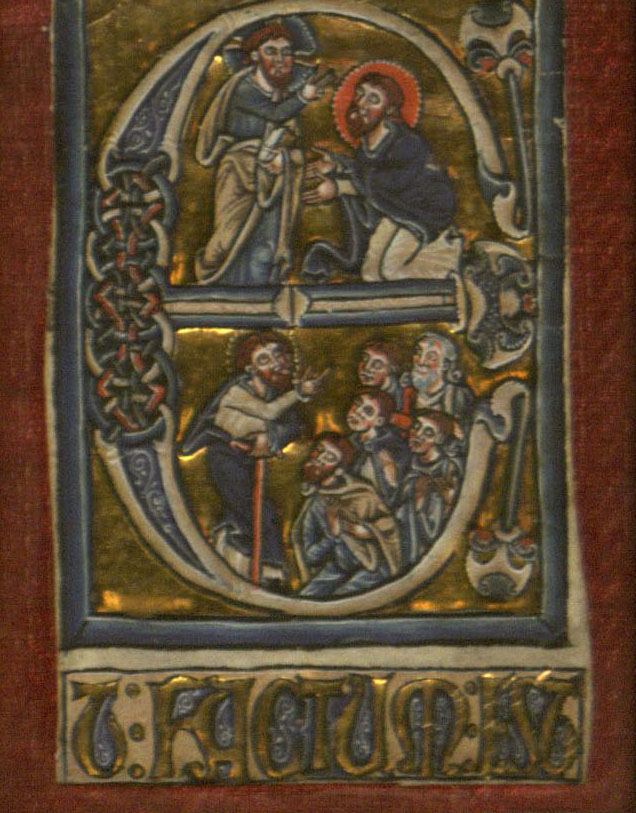

Another example of an inhabited initial, the letter E from the 14th-century breviary fragment, houses two scenes. On the top St. Peter kneels before Christ, and on the bottom Christ preaches to his followers. This illuminated initial E is a single page from the original 14th-century volume. The text below the letter reads “Et factum es,” which may be a line from Luke 9:18, sometimes called Peter’s Declaration because it describes Peter recognizing the divinity of Christ. The top half of the letter E depicts a man kneeling before Christ, which would correspond with the passage from Luke.

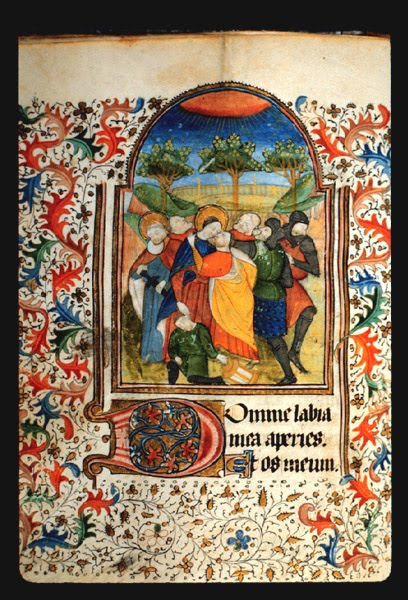

The 15th-century Flemish Book of Hours contains ten pages that depict entire miniature paintings. These paintings do not fit inside letters, but sit on their own, above the text. Books of Hours frequently include more illumination than other texts because pictures helped readers to recognize where one prayer started and another began;[2] this was particularly important because medieval manuscripts did not divide texts into chapters the way modern books do. Often the paintings do not directly parallel the narrative of the text, and instead show moments in the life of Christ. Therefore, although the pictures do not show the actual content of prayers, they still allow readers to mark which prayer they are reading. The two pictures seen here depict the Kiss of Judas on f. 39 v, and the Crucifixion on f. 56 v. Illuminations from this Book of Hours of the Virgin Mary from Rennes in Brittany, France, are available digitally on the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections website.

The 15th-century Flemish Book of Hours contains ten pages that depict entire miniature paintings. These paintings do not fit inside letters, but sit on their own, above the text. Books of Hours frequently include more illumination than other texts because pictures helped readers to recognize where one prayer started and another began;[2] this was particularly important because medieval manuscripts did not divide texts into chapters the way modern books do. Often the paintings do not directly parallel the narrative of the text, and instead show moments in the life of Christ. Therefore, although the pictures do not show the actual content of prayers, they still allow readers to mark which prayer they are reading. The two pictures seen here depict the Kiss of Judas on f. 39 v, and the Crucifixion on f. 56 v. Illuminations from this Book of Hours of the Virgin Mary from Rennes in Brittany, France, are available digitally on the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections website.

Although this describes a few of the most impressive illuminations from the four selected texts, all of these texts (except the breviary fragment with the letter E) include several additional examples of illuminations. All of these pictures display amazing detail, especially considering that they are only a few inches tall. This level of detail highlights the importance of books in medieval culture. Scribes wrote manuscripts by hand and with great care. Books were highly prized and expensive items; patrons spent a lot of money when they bought books. Even today, when modern readers look at illuminated manuscripts, they can appreciate the careful artistry used to write and illustrate these texts.

Although this describes a few of the most impressive illuminations from the four selected texts, all of these texts (except the breviary fragment with the letter E) include several additional examples of illuminations. All of these pictures display amazing detail, especially considering that they are only a few inches tall. This level of detail highlights the importance of books in medieval culture. Scribes wrote manuscripts by hand and with great care. Books were highly prized and expensive items; patrons spent a lot of money when they bought books. Even today, when modern readers look at illuminated manuscripts, they can appreciate the careful artistry used to write and illustrate these texts.

Notes

- de Hamel, Christopher. The British Library Guide to Manuscript Illumination: History and Techniques. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

- ibid.

Manus 1, Catholic Church. [Book of Hours : Use of Rennes], 1420-1430. Gift of Philip D. Sang.

Manus 3, Catholic Church. [Book of Hours : Use of Rome]. (Italy), 15th c. History of acquisition unknown; possibly the gift of Philip D. Sang.

Manus 7, Alberti, Leon Battista. De Pictura [On Painting], 1485. Gift of Bern Dibner.

Manus 31, Breviary (?) [fragment]. (France), early 14th c. Gift of Eugene L. Gabarty.