The History of the Indian Tribes of North America

With Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs. Embellished with One Hundred and Twenty Portraits from the Indian Gallery in the Department of War, at Washington. Philadelphia, 1837-1844. 3 vols., by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall.

September 4, 2013

Description by Cassandra N. Berman, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD student in history.

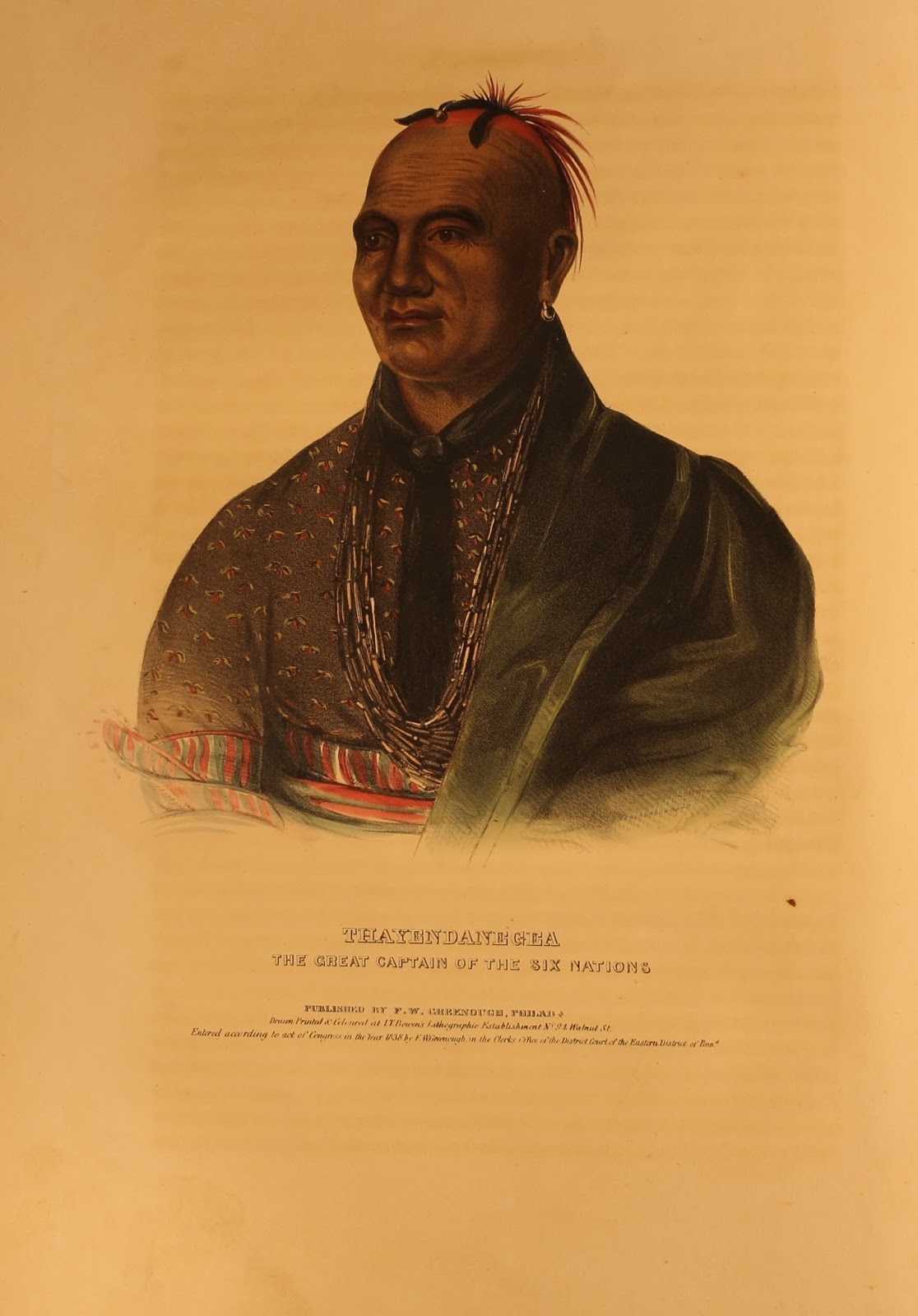

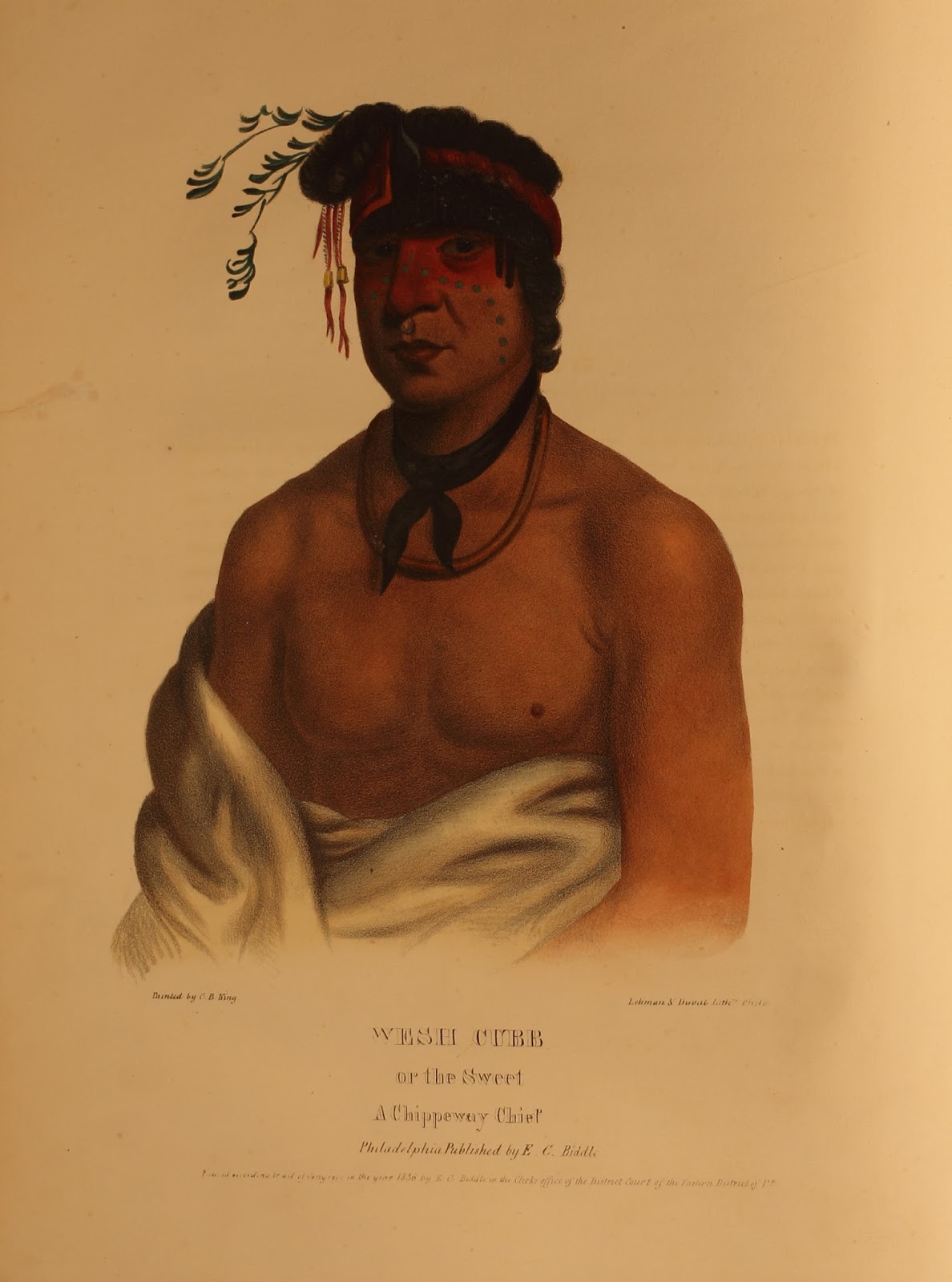

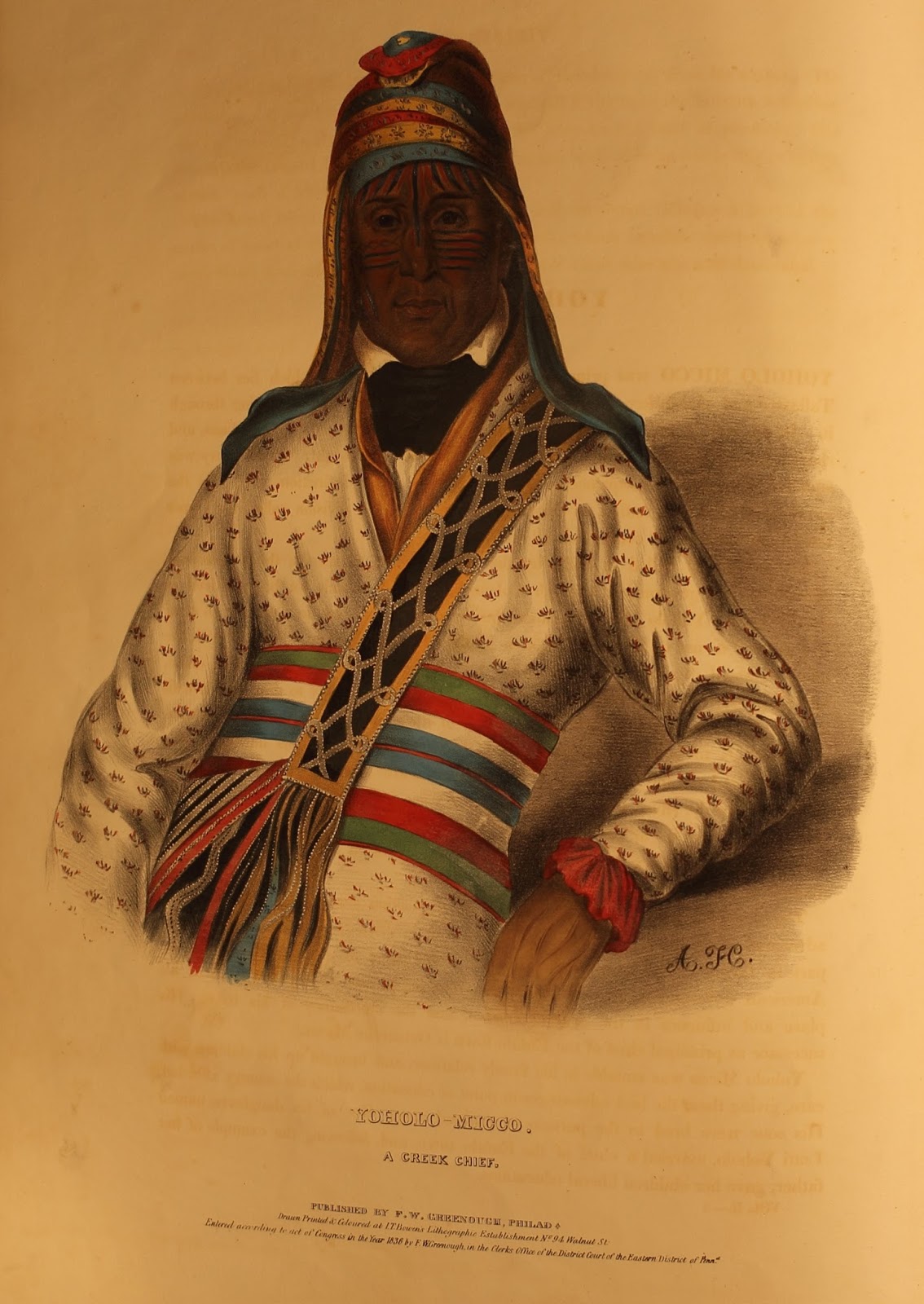

The “History of the Indian Tribes of North America,” first published from 1837 to 1844, features biographies and portraits of Native American leaders, many of whom had been active in negotiating treaties with the federal government. With 120 color lithographs spread over three volumes—and each volume measuring over 20 inches high—the “History” is an important example of 19th-century publishing, printmaking and illustration. It is also significant for its subject matter, reflecting contradictory, concurrent efforts to document the way of life of American Indians and to initiate their relocation westward as part of the Indian Removal Act, authorized by President Andrew Jackson in 1830. Finally, the story behind the publication—of the author and of the creation, destruction and ultimate preservation of the images—is almost as interesting as the volumes themselves. Brandeis University is very fortunate, then, to have a complete set of the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” in its rare book collection in the Department of Archives and Special Collections.

The “History of the Indian Tribes of North America,” first published from 1837 to 1844, features biographies and portraits of Native American leaders, many of whom had been active in negotiating treaties with the federal government. With 120 color lithographs spread over three volumes—and each volume measuring over 20 inches high—the “History” is an important example of 19th-century publishing, printmaking and illustration. It is also significant for its subject matter, reflecting contradictory, concurrent efforts to document the way of life of American Indians and to initiate their relocation westward as part of the Indian Removal Act, authorized by President Andrew Jackson in 1830. Finally, the story behind the publication—of the author and of the creation, destruction and ultimate preservation of the images—is almost as interesting as the volumes themselves. Brandeis University is very fortunate, then, to have a complete set of the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” in its rare book collection in the Department of Archives and Special Collections.

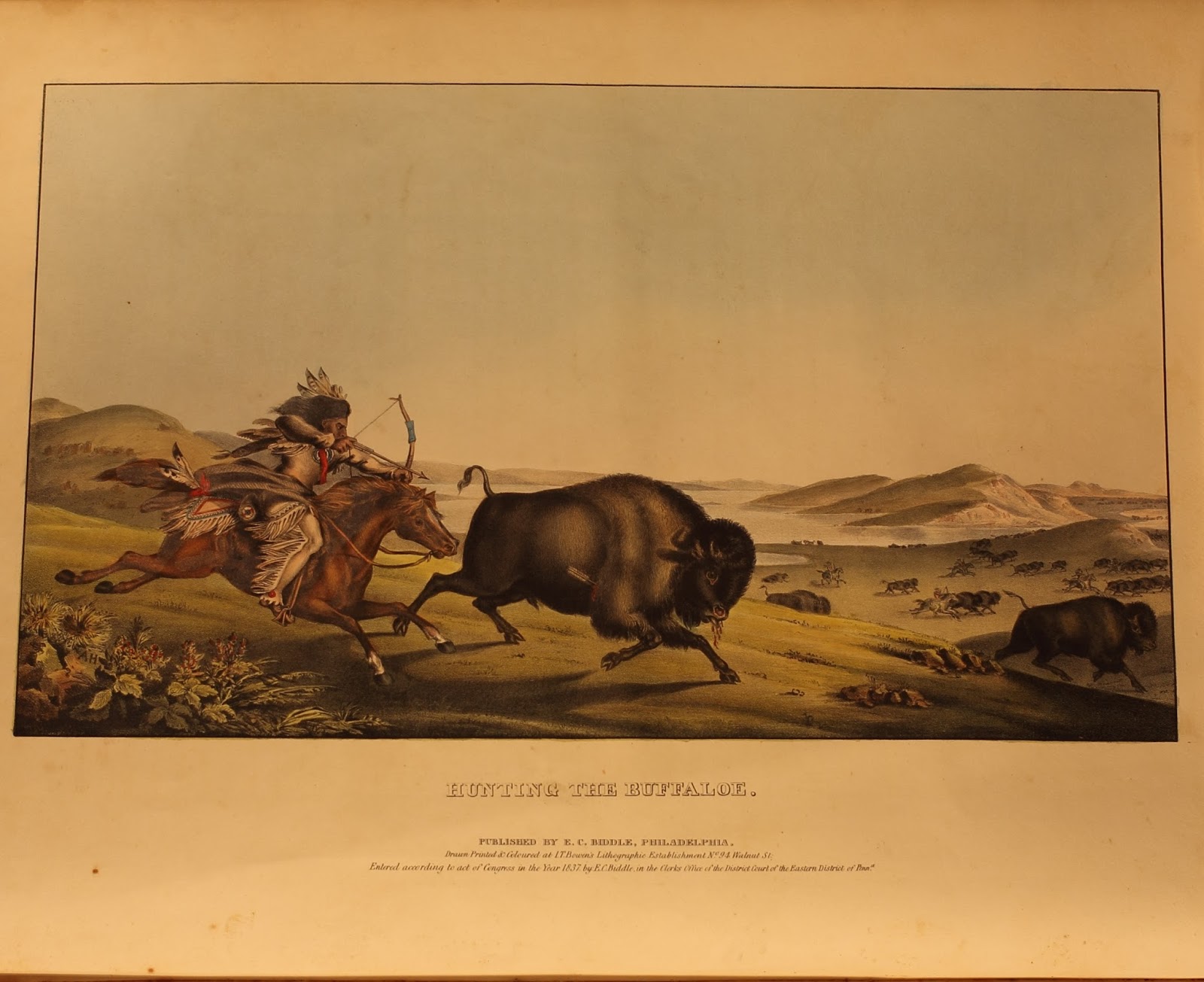

As an object of printing history and material culture, the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” is a vibrant example of 19th-century lithography. Lithography is a printing process in which images are drawn in a greasy ink onto a flat stone, and the stone is then pressed onto paper. Invented in the late 18th century, lithographic techniques had become increasingly advanced by the 1830s. Yet color lithography—printing images in multiple hues and in subtle gradations—remained problematic until the development of chromolithography in the 1840s and later. [1] The lithographs of the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” are striking for their rich colors—colors that were for the most part added by hand, after the images themselves were already printed. This technique was also used by John James Audubon in his “Birds of North America,” which features some of the most iconic American lithographs of the 19th century. The lithographs in these works represent both great advancement in printing processes and the beauty of handwork.

As an object of printing history and material culture, the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” is a vibrant example of 19th-century lithography. Lithography is a printing process in which images are drawn in a greasy ink onto a flat stone, and the stone is then pressed onto paper. Invented in the late 18th century, lithographic techniques had become increasingly advanced by the 1830s. Yet color lithography—printing images in multiple hues and in subtle gradations—remained problematic until the development of chromolithography in the 1840s and later. [1] The lithographs of the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” are striking for their rich colors—colors that were for the most part added by hand, after the images themselves were already printed. This technique was also used by John James Audubon in his “Birds of North America,” which features some of the most iconic American lithographs of the 19th century. The lithographs in these works represent both great advancement in printing processes and the beauty of handwork.

The “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” is also the product of a particular moment in which Native American culture was increasingly becoming a subject of study and, for some, of preservation—just as the government’s formal policies toward Indian tribes fixated on removal. In 1819, the War Department, for example, oversaw the Indian Civilization Fund Act, which provided financial support for the schooling of Indian children. While this was seen as a humanitarian effort by some, the Act’s goal of “civilizing” Indian children resulted in their removal from their families, communities and ways of life. [2] And it was just after the “History”’s publication that the Indian Removal Act culminated in the infamous Cherokee Trail of Tears, in which a 1,000-mile forced relocation resulted in the deaths of thousands of Cherokee Indians. Around this same time, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs at the War Department, Thomas L. McKenney, was amassing an impressive museum of objects, portraits, documents, books and other materials related to Native American life. This may have been because McKenney admired some aspects of Indian culture. But it also had a more troubling impetus: as the chief architect of Indian removal, McKenney believed that Indians would soon disappear, assimilating so completely into white Euro-American society that all that would remain of Indian material culture would be in his museum. [3] The “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” is McKenney’s book, and the lithographs in it are a product of his museum and his work at the War Department.

The “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” is also the product of a particular moment in which Native American culture was increasingly becoming a subject of study and, for some, of preservation—just as the government’s formal policies toward Indian tribes fixated on removal. In 1819, the War Department, for example, oversaw the Indian Civilization Fund Act, which provided financial support for the schooling of Indian children. While this was seen as a humanitarian effort by some, the Act’s goal of “civilizing” Indian children resulted in their removal from their families, communities and ways of life. [2] And it was just after the “History”’s publication that the Indian Removal Act culminated in the infamous Cherokee Trail of Tears, in which a 1,000-mile forced relocation resulted in the deaths of thousands of Cherokee Indians. Around this same time, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs at the War Department, Thomas L. McKenney, was amassing an impressive museum of objects, portraits, documents, books and other materials related to Native American life. This may have been because McKenney admired some aspects of Indian culture. But it also had a more troubling impetus: as the chief architect of Indian removal, McKenney believed that Indians would soon disappear, assimilating so completely into white Euro-American society that all that would remain of Indian material culture would be in his museum. [3] The “History of the Indian Tribes of North America” is McKenney’s book, and the lithographs in it are a product of his museum and his work at the War Department.

Thomas L. McKenney was a complex man, as was his relationship to the War Department and the Jackson administration. McKenney was with the War Department from 1824 until he was dismissed from his position in 1830. The reasons for his dismissal are not entirely clear, though it seems that McKenney had angered some with the substantial time and funds he directed toward his Indian museum, even as it was proving popular with the public. McKenney had also complicated his stance on Indian removal, as the Indian Removal Act was not implemented in the way that McKenney had intended. McKenney did not approve of violently forcing unwilling tribes to move; nor did he intend the dissolution of tribal governments. When he asked the acting Secretary of War the reason for his dismissal, he was told, “General Jackson has long been satisfied that you are not in harmony with him, in his views in regard to the Indians.” McKenney later wrote to a friend, “I could never have been in harmony with any such views, or feelings.” McKenney may have advocated for Indian “civilization” and removal, but he could not support the inhumane ways with which these policies were implemented. [4]

Thomas L. McKenney was a complex man, as was his relationship to the War Department and the Jackson administration. McKenney was with the War Department from 1824 until he was dismissed from his position in 1830. The reasons for his dismissal are not entirely clear, though it seems that McKenney had angered some with the substantial time and funds he directed toward his Indian museum, even as it was proving popular with the public. McKenney had also complicated his stance on Indian removal, as the Indian Removal Act was not implemented in the way that McKenney had intended. McKenney did not approve of violently forcing unwilling tribes to move; nor did he intend the dissolution of tribal governments. When he asked the acting Secretary of War the reason for his dismissal, he was told, “General Jackson has long been satisfied that you are not in harmony with him, in his views in regard to the Indians.” McKenney later wrote to a friend, “I could never have been in harmony with any such views, or feelings.” McKenney may have advocated for Indian “civilization” and removal, but he could not support the inhumane ways with which these policies were implemented. [4]

It was after McKenney’s dismissal that he set to work on the “History” (as the title page makes clear, listing him as “late of the Indian department, Washington”). His work on the illustrations, however, began much earlier. As Superintendent of Indian Affairs, one of McKenney’s primary roles before the Removal Act was the negotiation of treaties with Indian tribes. He was so impressed with the various leaders who came to Washington that he commissioned portraitist Charles Bird King to paint the visitors—paintings that would nicely complement the other items in McKenney’s museum. When McKenney’s tenure with the War Department ended, he decided to bring King’s arresting images to the public by having them copied into lithographic form, and then publishing these lithographs along with biographies of the portrait subjects. This became the three-volume “History of the Indian Tribes of North America,” with text written by co-author James Hall. Though the financing and publication of the volumes proved quite difficult, nearly bankrupting McKenney, we are, in the end, fortunate that McKenney devoted his post–War Department years to this endeavor. King’s original portraits were eventually transferred to the Smithsonian, where they were displayed in the institution’s art gallery. In 1865, the gallery burned down, and most of King’s original works were destroyed. [5]

It was after McKenney’s dismissal that he set to work on the “History” (as the title page makes clear, listing him as “late of the Indian department, Washington”). His work on the illustrations, however, began much earlier. As Superintendent of Indian Affairs, one of McKenney’s primary roles before the Removal Act was the negotiation of treaties with Indian tribes. He was so impressed with the various leaders who came to Washington that he commissioned portraitist Charles Bird King to paint the visitors—paintings that would nicely complement the other items in McKenney’s museum. When McKenney’s tenure with the War Department ended, he decided to bring King’s arresting images to the public by having them copied into lithographic form, and then publishing these lithographs along with biographies of the portrait subjects. This became the three-volume “History of the Indian Tribes of North America,” with text written by co-author James Hall. Though the financing and publication of the volumes proved quite difficult, nearly bankrupting McKenney, we are, in the end, fortunate that McKenney devoted his post–War Department years to this endeavor. King’s original portraits were eventually transferred to the Smithsonian, where they were displayed in the institution’s art gallery. In 1865, the gallery burned down, and most of King’s original works were destroyed. [5]

What we have left of McKenney’s conflicted effort to preserve Native American culture through portraiture is now contained only in the pages of the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America.” While this publication has been reprinted many times, the Department of Archives and Special Collections at Brandeis University has one of the earliest editions of the set, with volumes printed in 1837, 1842 and 1844. Viewing these folios in person allows for a vibrant, truly colorful glimpse into this fraught period of American history.

What we have left of McKenney’s conflicted effort to preserve Native American culture through portraiture is now contained only in the pages of the “History of the Indian Tribes of North America.” While this publication has been reprinted many times, the Department of Archives and Special Collections at Brandeis University has one of the earliest editions of the set, with volumes printed in 1837, 1842 and 1844. Viewing these folios in person allows for a vibrant, truly colorful glimpse into this fraught period of American history.

Notes

Bamber Gascoigne, “How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Ink-Jet” (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1986), section 19, “Lithographs.”

Bamber Gascoigne, “How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Ink-Jet” (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1986), section 19, “Lithographs.”- For information on this act, see “Education” in the “Encyclopedia of North American Indians” (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1996).

- Herman J. Viola, “Thomas L. McKenney, Architect of America’s Early Indian Policy: 1816-1830” (Chicago: Sage Books, 1974), 237.

- Viola, 235.

Viola, 250.

Viola, 250.

Digitized volumes (from edition at the American Antiquarian Society):

McKenney, Thomas Loraine. “History of the Indian tribes of North America: with biographical sketches and anecdotes of the principal chiefs: embellished with one hundred … Philadelphia, 1837-1844. 3 vols. ” Available online through the Sabin Americana database.