14th-Century Italian Illuminated Breviary Leaf: Feast of Epiphany

February 28, 2008

Description by Adam Rutledge, Senior University Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in English and American Literature

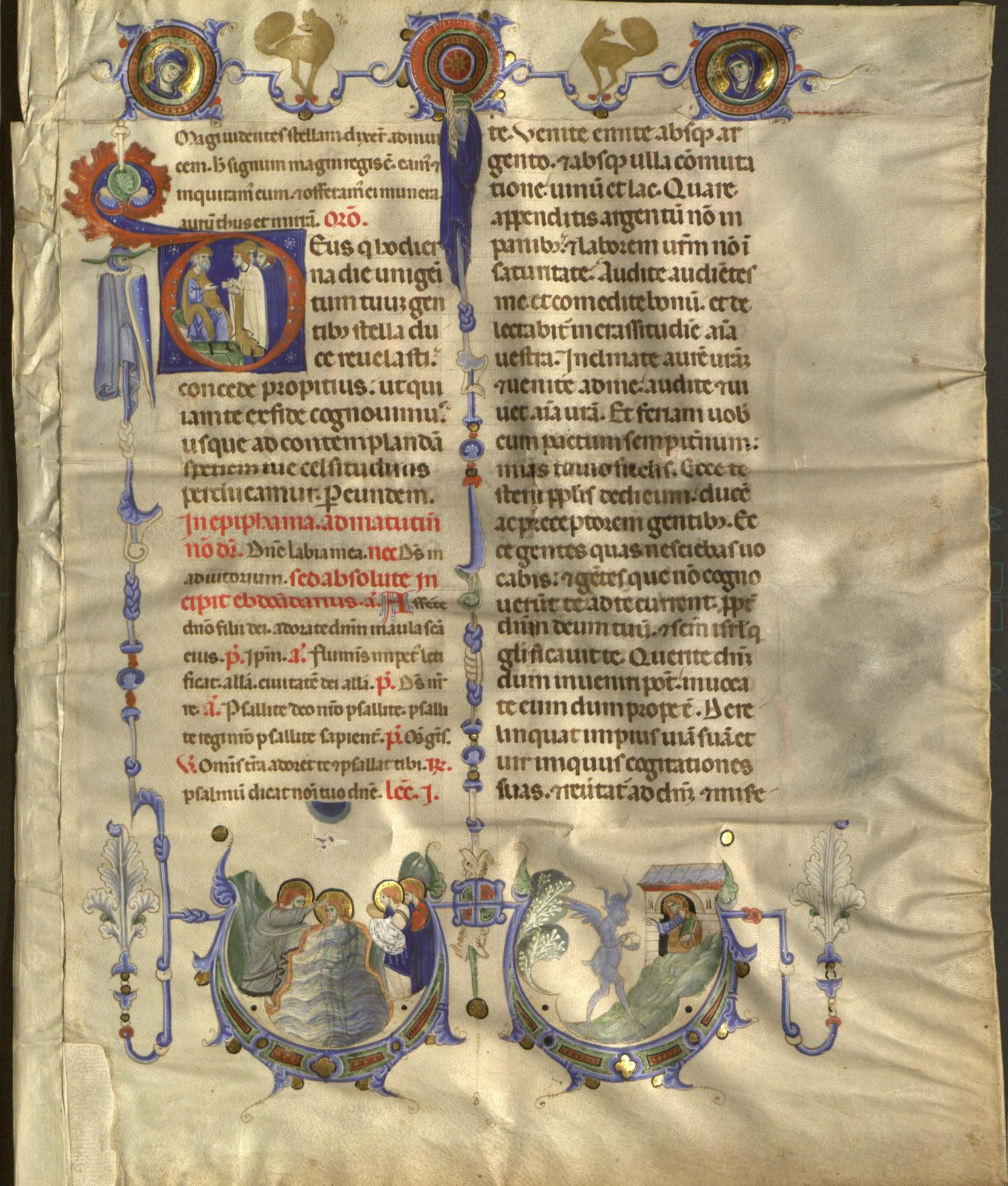

The Brevarium or Breviary is a book containing the offices, hymns and prayers for the canonical hours, which are appointed by the Catholic Church to be recited daily by priests and members of certain religious orders. The first of the seven canonical hours is matins, traditionally celebrated at daybreak, followed by lauds, prime, tierce, sext, nones, vespers and compline, the last of which is sung just before retiring. Nones, though traditionally sung at three in the afternoon, was gradually celebrated earlier and earlier, until it marked the middle of the day, giving us the English word “noon.” A simplified version of the breviary, known as the Book of Hours, was produced for laypeople, and many copies of both the Book of Hours and the Breviary contain numerous manuscript illuminations, providing some of the finest and most well-preserved examples of the art of the medieval period. This leaf, cut from a Medieval Latin breviary, contains the first part of the liturgy for matins on the Feast of the Epiphany.

The Brevarium or Breviary is a book containing the offices, hymns and prayers for the canonical hours, which are appointed by the Catholic Church to be recited daily by priests and members of certain religious orders. The first of the seven canonical hours is matins, traditionally celebrated at daybreak, followed by lauds, prime, tierce, sext, nones, vespers and compline, the last of which is sung just before retiring. Nones, though traditionally sung at three in the afternoon, was gradually celebrated earlier and earlier, until it marked the middle of the day, giving us the English word “noon.” A simplified version of the breviary, known as the Book of Hours, was produced for laypeople, and many copies of both the Book of Hours and the Breviary contain numerous manuscript illuminations, providing some of the finest and most well-preserved examples of the art of the medieval period. This leaf, cut from a Medieval Latin breviary, contains the first part of the liturgy for matins on the Feast of the Epiphany.

Epiphany, which means “appearance” or “revelation” in Greek, is celebrated on the sixth of January, the day after Christmastide concludes (the “twelve days of Christmas” end on January fifth). The festival marks, for Western Christians, the Journey of the Magi to visit the infant Christ, as described in the second chapter of Matthew’s gospel:

Epiphany, which means “appearance” or “revelation” in Greek, is celebrated on the sixth of January, the day after Christmastide concludes (the “twelve days of Christmas” end on January fifth). The festival marks, for Western Christians, the Journey of the Magi to visit the infant Christ, as described in the second chapter of Matthew’s gospel:

9 When they had heard the king, they departed; and, lo, the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. 10 When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy. 11 And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh (Matthew 2:9-11 [KJV]).

In the Eastern Church, this festival has different associations; it celebrates the baptism of Jesus in the river Jordan, also called the Theophany, the manifestation of God to the world, since this story describes the descent of the holy spirit in the form of a dove upon Jesus at the time of his baptism, during which the voice of God was heard, saying: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (cf. Matthew 3).

In the Eastern Church, this festival has different associations; it celebrates the baptism of Jesus in the river Jordan, also called the Theophany, the manifestation of God to the world, since this story describes the descent of the holy spirit in the form of a dove upon Jesus at the time of his baptism, during which the voice of God was heard, saying: “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (cf. Matthew 3).

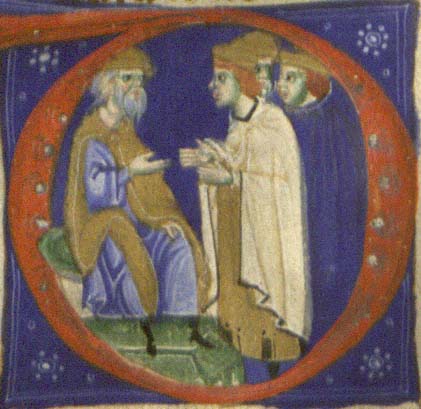

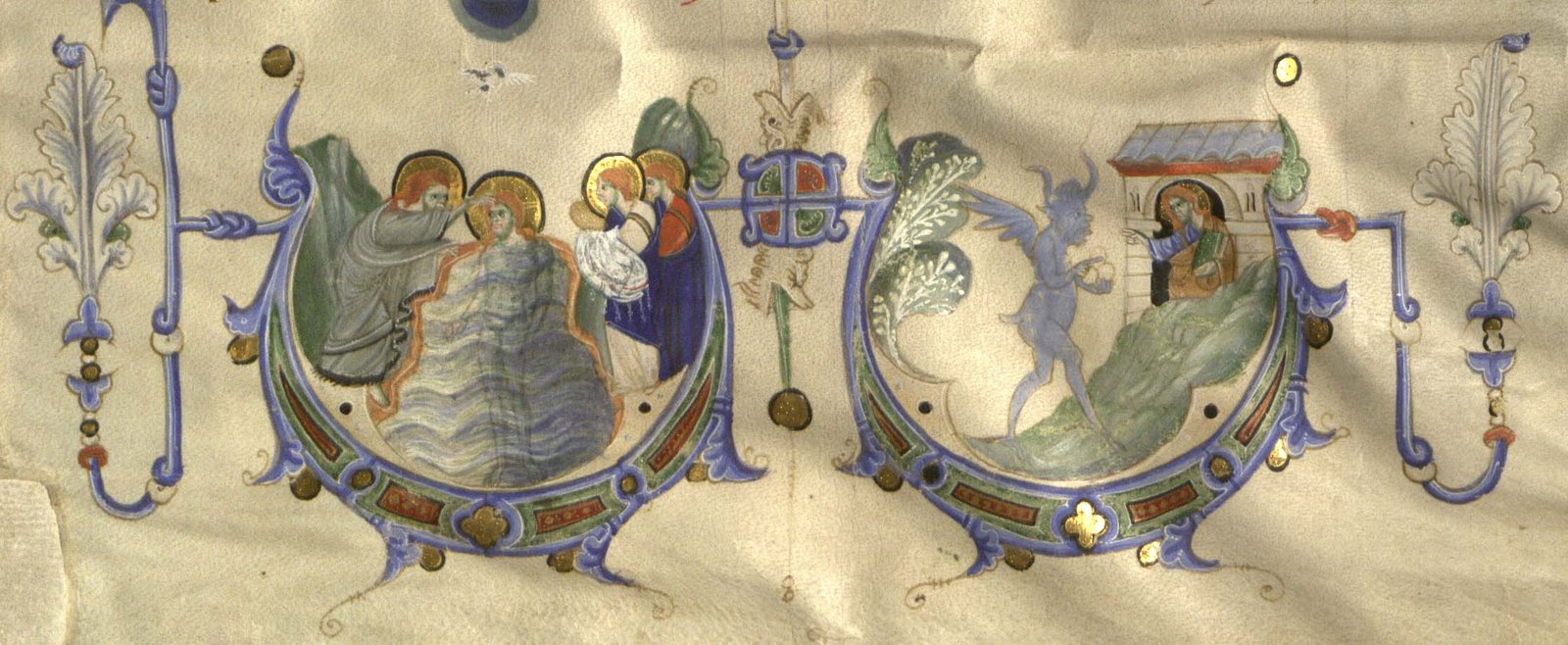

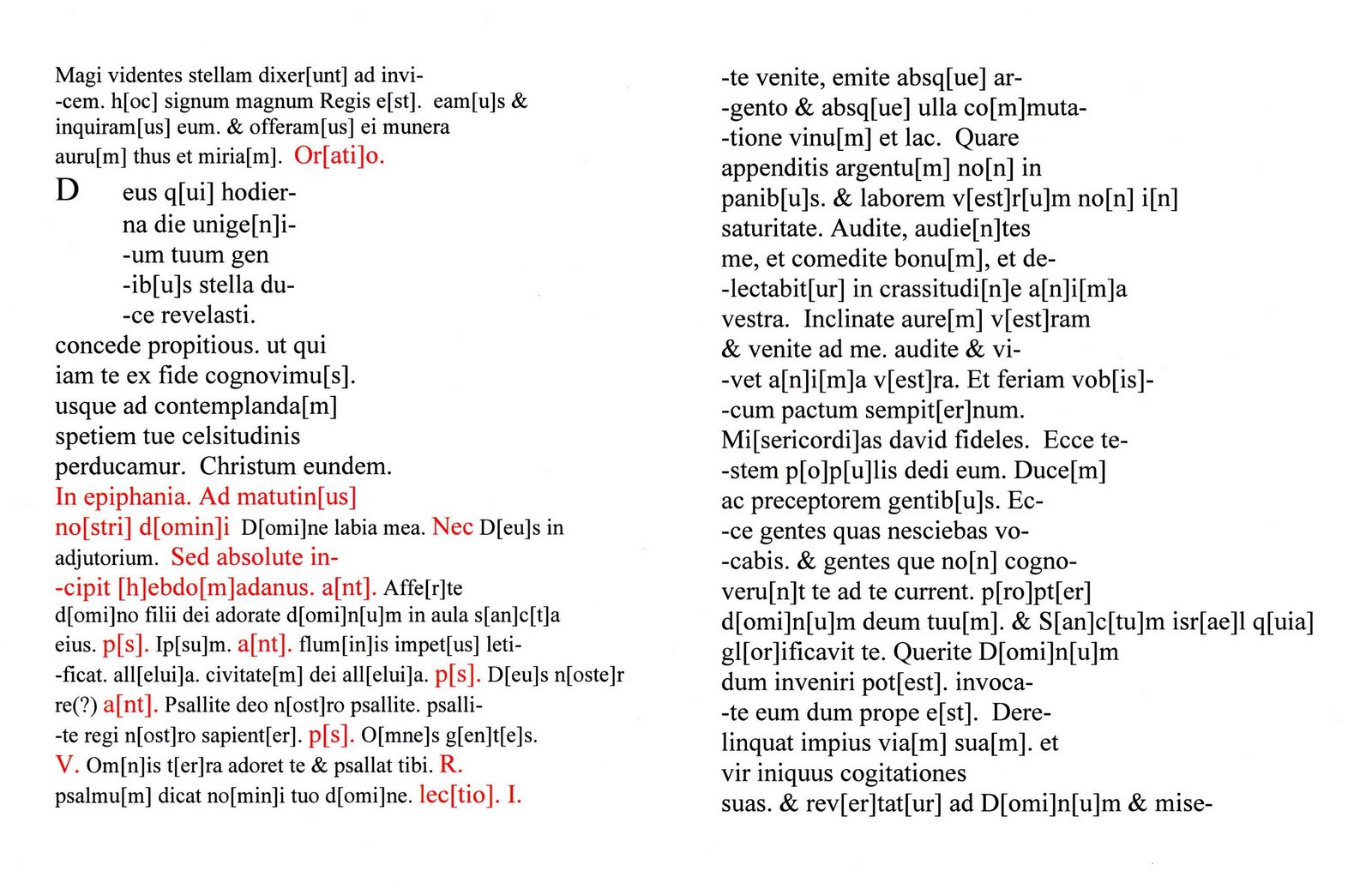

These two different traditions of celebrating Epiphany are important in relation to this leaf in that the imagery used in the illuminations partakes of both the Western and the Eastern traditions, despite the fact that this text was written in Latin in northern Italy and thus was clearly produced for the Western Church. These illuminations are particularly striking and well-preserved, and they include, on the recto, one historiated initial, two large scenes (7 x 6 cm. each) painted in the lower margin, and an elaborate three-quarter border, while the verso contains two fine initials in blue, red and white with a partial border. The first of these illuminations follows the Western tradition of associating Epiphany with the Journey of the Magi, as the historiated initial “D” of Deus contains within it a miniature of the visit of the three magi to King Herod as they were journeying toward Bethlehem to see the infant Jesus, an event described in Matthew, chapter two:

1 Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem, 23 When Herod the king had heard these things, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him….7 Then Herod, when he had privily called the wise men, inquired of them diligently what time the star appeared. 8 And he sent them to Bethlehem, and said, Go and search diligently for the young child; and when ye have found him, bring me word again, that I may come and worship him also (Matthew 2:1-3,7-8 [KJV]). Saying, Where is he that is born King of the Jews? for we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him.

Herod is depicted bearded, seated on a green chair to the left, clothed in blue and brown, while before him, on the right, stand the three wise men, the first clothed in white and brown, the second in blue such that his body nearly fades entirely into the blue background, and the third shown standing behind the others, with only his head visible.

Herod is depicted bearded, seated on a green chair to the left, clothed in blue and brown, while before him, on the right, stand the three wise men, the first clothed in white and brown, the second in blue such that his body nearly fades entirely into the blue background, and the third shown standing behind the others, with only his head visible.

In addition to this historiated initial D, two small roundels appear in the upper margin, each depicting a woman’s face, hooded by a blue robe and surrounded by a halo. Because of the close links between Epiphany and the story of the birth of Jesus, with Epiphany following immediately after the conclusion of Christmas celebrations, and because of the blue color of the robe and the gold-leaf halo that surround this woman, these roundels may be provisionally identified as depicting the Virgin Mary, further emphasizing the practice of the Latin West in its celebrations of this festival.

In addition to this historiated initial D, two small roundels appear in the upper margin, each depicting a woman’s face, hooded by a blue robe and surrounded by a halo. Because of the close links between Epiphany and the story of the birth of Jesus, with Epiphany following immediately after the conclusion of Christmas celebrations, and because of the blue color of the robe and the gold-leaf halo that surround this woman, these roundels may be provisionally identified as depicting the Virgin Mary, further emphasizing the practice of the Latin West in its celebrations of this festival.

By contrast, the two rather more elaborate scenes painted in the lower margin partake more of traditional Eastern associations. The first is a depiction of the Baptism of Jesus in the left portion of the lower margin. Jesus is portrayed in the waters of the Jordan River, while John the Baptist, clothed in a grey robe with a black fringe, stands on the shore, reaching out to perform the baptism. Above Jesus, a dove is shown descending, representing the descent of the Holy Spirit at the time of the baptism (cf. Mark 1:10, Matthew 3:16). On the opposite bank stand two disciples, one robed in blue and white, the other in blue and orange, most likely Andrew and Peter, who are described in the gospel of John (John 1:35-42) as having witnessed this event. All four figures are portrayed with haloes surrounding their heads, painted in gold leaf. While the most likely explanation for this illumination is an Eastern influence in the manuscript, in the West baptisms were often performed on Epiphany, which could possibly account for the presence of this image.

By contrast, the two rather more elaborate scenes painted in the lower margin partake more of traditional Eastern associations. The first is a depiction of the Baptism of Jesus in the left portion of the lower margin. Jesus is portrayed in the waters of the Jordan River, while John the Baptist, clothed in a grey robe with a black fringe, stands on the shore, reaching out to perform the baptism. Above Jesus, a dove is shown descending, representing the descent of the Holy Spirit at the time of the baptism (cf. Mark 1:10, Matthew 3:16). On the opposite bank stand two disciples, one robed in blue and white, the other in blue and orange, most likely Andrew and Peter, who are described in the gospel of John (John 1:35-42) as having witnessed this event. All four figures are portrayed with haloes surrounding their heads, painted in gold leaf. While the most likely explanation for this illumination is an Eastern influence in the manuscript, in the West baptisms were often performed on Epiphany, which could possibly account for the presence of this image.

The portrayal of the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness on the right side of the lower margin is even more unusual. Jesus, depicted robed in blue and brown, clutches a bible in his left hand while he extends his right hand in a liturgical gesture of blessing. He stands in the doorway of a shelter of decidedly medieval European architecture, and the darkness of the doorway is set off by a gold-leaf halo that surrounds his head. Approaching him from the left is Satan, painted in blue with wings, horns and a tail, carrying with him three loaves of bread, illustrating a passage from the gospel of Luke:

The portrayal of the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness on the right side of the lower margin is even more unusual. Jesus, depicted robed in blue and brown, clutches a bible in his left hand while he extends his right hand in a liturgical gesture of blessing. He stands in the doorway of a shelter of decidedly medieval European architecture, and the darkness of the doorway is set off by a gold-leaf halo that surrounds his head. Approaching him from the left is Satan, painted in blue with wings, horns and a tail, carrying with him three loaves of bread, illustrating a passage from the gospel of Luke:

1 And Jesus being full of the Holy Ghost returned from Jordan, and was led by the Spirit into the wilderness, 2 Being forty days tempted of the devil. And in those days he did eat nothing: and when they were ended, he afterward hungered. 3 And the devil said unto him, If thou be the Son of God, command this stone that it be made bread. 4 And Jesus answered him, saying, It is written, That man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word of God (Luke 4:1-4 [KJV], cf. Matthew 4:1-4, Mark 1:13).

In all three synoptic gospels the story of the temptation of Jesus immediately follows the story of Jesus’ baptism, and thus the scribe may have taken inspiration from these passages as a continuation of the imagery of the Eastern Church. However, it is also possible to see this passage as having an oblique relation to the text from Isaiah 55, which is the first reading for Epiphany and which is the text present just above this illumination. Verses two and three of this passage read as follows:

In all three synoptic gospels the story of the temptation of Jesus immediately follows the story of Jesus’ baptism, and thus the scribe may have taken inspiration from these passages as a continuation of the imagery of the Eastern Church. However, it is also possible to see this passage as having an oblique relation to the text from Isaiah 55, which is the first reading for Epiphany and which is the text present just above this illumination. Verses two and three of this passage read as follows:

2 Wherefore do ye spend money for that which is not bread? and your labour for that which satisfieth not? hearken diligently unto me, and eat ye that which is good, and let your soul delight itself in fatness. 3 Incline your ear, and come unto me: hear, and your soul shall live; and I will make an everlasting covenant with you, even the sure mercies of David. (Isaiah 55:2-3 [KJV])

The parallels here are obvious, yet the narrative of the Temptation in the Wilderness is not generally a story associated with Epiphany, thus raising interesting questions about medieval hermeneutics, especially as practiced in the relations between text and imagery in illuminated religious manuscripts. The artist has paired the verse written above his work, “hearken diligently unto me, and eat ye that which is good, and let your soul delight itself in fatness,” with an illustration of another text, “man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word of God.” It is thus possible to argue that the illuminator of this manuscript, by picking this particular topic for his art, was in effect performing a reading of the passage quoted in the text above the image, choosing his own New Testament parallel to the Hebrew Bible verses appointed for the day’s reading, a parallel fitting both in its relation to the Baptism of Jesus, which the church celebrates on Epiphany in the East, and in relation to the play on consuming food that is ultimately unsatisfying versus listening to the word of God, as seen in the passage from Isaiah.

The parallels here are obvious, yet the narrative of the Temptation in the Wilderness is not generally a story associated with Epiphany, thus raising interesting questions about medieval hermeneutics, especially as practiced in the relations between text and imagery in illuminated religious manuscripts. The artist has paired the verse written above his work, “hearken diligently unto me, and eat ye that which is good, and let your soul delight itself in fatness,” with an illustration of another text, “man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word of God.” It is thus possible to argue that the illuminator of this manuscript, by picking this particular topic for his art, was in effect performing a reading of the passage quoted in the text above the image, choosing his own New Testament parallel to the Hebrew Bible verses appointed for the day’s reading, a parallel fitting both in its relation to the Baptism of Jesus, which the church celebrates on Epiphany in the East, and in relation to the play on consuming food that is ultimately unsatisfying versus listening to the word of God, as seen in the passage from Isaiah.

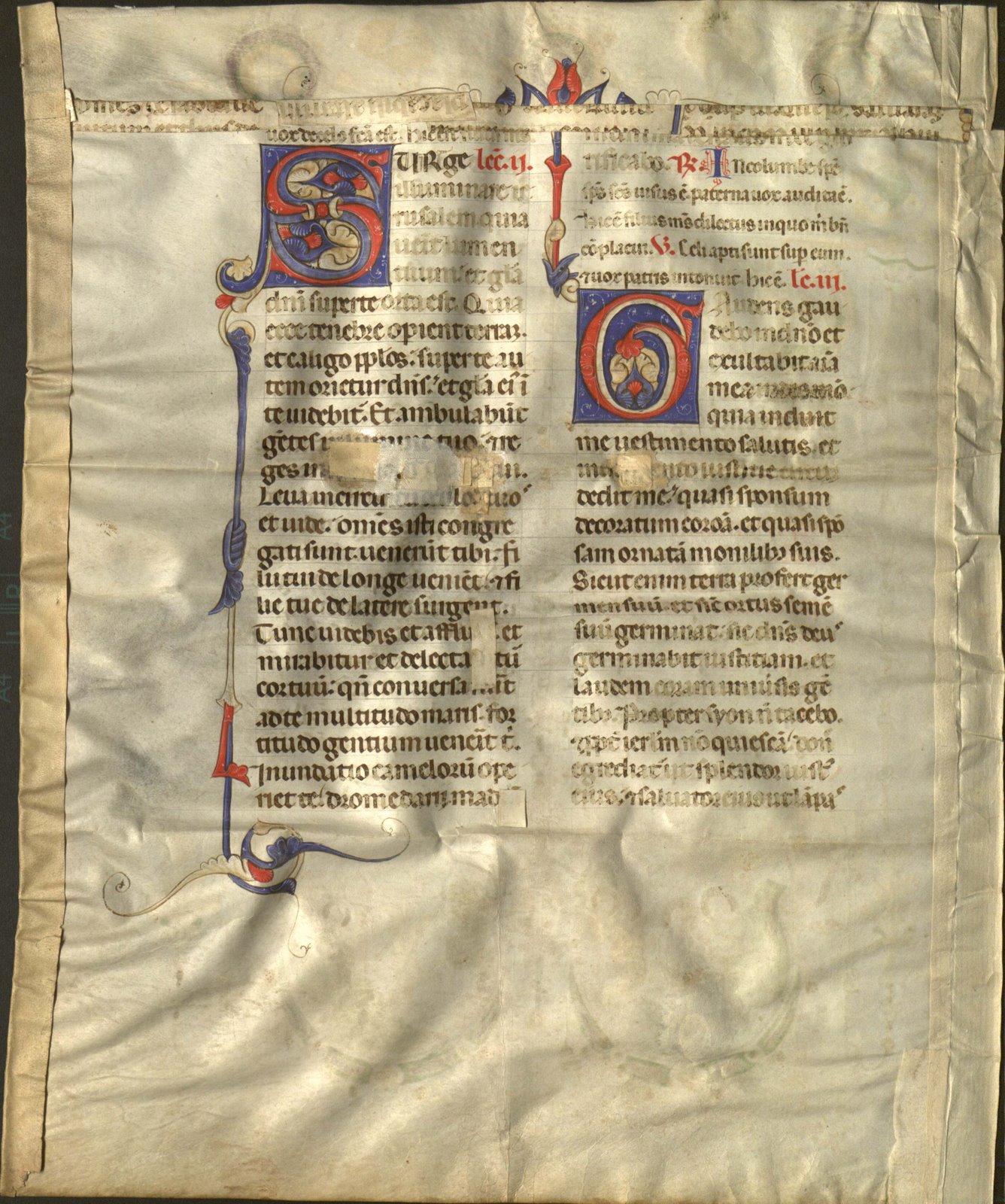

With these close associations between text and illumination in mind, a discussion of the text found on this leaf is in order, followed by a full transcription and translation. The recto of the leaf begins with an antiphon for Epiphany (Magi videntes stellam…), the use of which on Epiphany is attested in numerous breviaries and antiphoners (Cursus antiphon c3654). [1] Next is a short prayer (Deus qui hodierna?), in which the initial D of Deus is illuminated (Cursus prayer o1631).[2] This series of prayers is followed by three scripture readings from the book of Isaiah: Is. 55:1ff., 60:1ff, and 61:10ff, the text of which follows closely, but not exactly, the Vulgata Clementina. These are followed by a series of antiphons and psalms which mirror almost exactly those sung on Epiphany in the St. Albans Breviary (f. 51 r.), thus suggesting that this set of short prayers was one in wide use in the West as part of the celebration of this feast. These readings were appointed for use on Epiphany by at least one medieval rubric, the Ordo Romanus XIIIa, in which is written:

With these close associations between text and illumination in mind, a discussion of the text found on this leaf is in order, followed by a full transcription and translation. The recto of the leaf begins with an antiphon for Epiphany (Magi videntes stellam…), the use of which on Epiphany is attested in numerous breviaries and antiphoners (Cursus antiphon c3654). [1] Next is a short prayer (Deus qui hodierna?), in which the initial D of Deus is illuminated (Cursus prayer o1631).[2] This series of prayers is followed by three scripture readings from the book of Isaiah: Is. 55:1ff., 60:1ff, and 61:10ff, the text of which follows closely, but not exactly, the Vulgata Clementina. These are followed by a series of antiphons and psalms which mirror almost exactly those sung on Epiphany in the St. Albans Breviary (f. 51 r.), thus suggesting that this set of short prayers was one in wide use in the West as part of the celebration of this feast. These readings were appointed for use on Epiphany by at least one medieval rubric, the Ordo Romanus XIIIa, in which is written:

In theophania similiter lectiones tres de Esaia propheta. Prima lectio sic continent in capite: Omnes scientes venite ad aquas. Secunda lectio: Surge, inluminare, Hierusalem. Tertia lectio: Gaudens gaudebo in domino.

[Likewise in Epiphany there are three readings from the prophet Isaiah. The first reading begins: Omnes scientes venite ad aquas (Is. 55:1ff); the second reading: Surge, inluminare, Hierusalem (Is. 60:1ff); and the third reading: Gaudens gaudebo in domino (Is. 61:10ff.)]

(Andrieu, Michel. Les Ordines Romani du Haut Moyen Age, v.2. (Louvain: Specilegium Sacrum Lovaniense Administration, 1971): 487)

These readings from Isaiah would have been followed by readings from the sermons of Augustine, Gregory, Jerome, Ambrose, or others, though this leaf contains only the three scripture readings.

These readings from Isaiah would have been followed by readings from the sermons of Augustine, Gregory, Jerome, Ambrose, or others, though this leaf contains only the three scripture readings.

On the recto of the leaf, the text is fairly well preserved, though it would appear that perhaps two lines of text are missing from the top of the page, the result of a foreshortening of the leaf, likely for display purposes, sometime in the past. In addition, in one place the leaf has suffered damage that has corrupted a portion of the text, though fortunately this is in one of the scriptural quotations and this the damaged words may be easily reconstructed from other sources (Mi[sericordi]as david fideles). The verso of the leaf has suffered much more damage, likely as a result of the recto of the leaf, with its several illuminations, having been placed on display, while the verso was allowed to be damaged in the process of framing, etc. However, since the text on the verso is drawn from the second and third scripture lessons appointed for the day, dramatically faded or otherwise damaged portions may be reconstructed with relative ease. The one other puzzling textual element is the presence of the letters “re” after Deus noster in one of the prayers on the recto of the leaf. This lettering is not present in the St. Albans breviary, and I have not been able to make sense of its meaning in the text; it contains no abbreviation marks. Otherwise the text is quite readable, written in a heavily abbreviated but clean gothic book hand in two sizes, with psalms, antiphons, etc. indicated in red, as is customary.

Below follows a transcription and translation of the text found on this leaf, with the translation of the scriptural passages taken from the King James translation of the Bible. In the Latin transcription, letters in brackets were elided in the original text.

Below follows a transcription and translation of the text found on this leaf, with the translation of the scriptural passages taken from the King James translation of the Bible. In the Latin transcription, letters in brackets were elided in the original text.

[Antiphon:] The Magi, seeing the star, said to one another: “This is the great sign of a king. Let us go and seek him and offer to him gifts – gold, frankincense and myrrh.”

Prayer. O God, you who on this day revealed your only-begotten son to the people by the guidance of a star, graciously grant, that we who know you now by faith may be led on to the contemplation of your splendor. Through the same Jesus Christ.

On Epiphany. At the matins of our Lord: O Lord open my lips. Not: O God, come to my assistance. But the weekly antiphon simply begins: Bring to the Lord, you sons of God, worship the Lord in his holy temple (cf. Ps. 28:1-2). Psalm: The same (i.e. Ps. 28). Antiphon: The fury of the river delights, alleluia, the city of God, alleluia (cf. Ps. 45:5). Psalm: Our God. Antiphon: Sing psalms to our God, sing psalms, sing psalms wisely to our king (cf. Ps. 46:7). Psalm: All the peoples. Call: Let all the earth worship you and sing psalms to you. Response: Let it sing a psalm to your name, O Lord (cf. Ps. 65:4). Reading I: (Isaiah 55:1-7a [King James Version])

1 [Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters, and he that hath no money;] come ye, buy, and eat; yea, come, buy wine and milk without money and without price. 2 Wherefore do ye spend money for that which is not bread? and your labour for that which satisfieth not? hearken diligently unto me, and eat ye that which is good, and let your soul delight itself in fatness. 3 Incline your ear, and come unto me: hear, and your soul shall live; and I will make an everlasting covenant with you, even the sure mercies of David. 4 Behold, I have given him for a witness to the people, a leader and commander to the people. 5 Behold, thou shalt call a nation that thou knowest not, and nations that knew not thee shall run unto thee because of the LORD thy God, and for the Holy One of Israel; for he hath glorified thee. 6 Seek ye the LORD while he may be found, call ye upon him while he is near: 7 Let the wicked forsake his way, and the unrighteous man his thoughts: and let him return unto the LORD, and he will have mercy [upon him.]

1 [Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters, and he that hath no money;] come ye, buy, and eat; yea, come, buy wine and milk without money and without price. 2 Wherefore do ye spend money for that which is not bread? and your labour for that which satisfieth not? hearken diligently unto me, and eat ye that which is good, and let your soul delight itself in fatness. 3 Incline your ear, and come unto me: hear, and your soul shall live; and I will make an everlasting covenant with you, even the sure mercies of David. 4 Behold, I have given him for a witness to the people, a leader and commander to the people. 5 Behold, thou shalt call a nation that thou knowest not, and nations that knew not thee shall run unto thee because of the LORD thy God, and for the Holy One of Israel; for he hath glorified thee. 6 Seek ye the LORD while he may be found, call ye upon him while he is near: 7 Let the wicked forsake his way, and the unrighteous man his thoughts: and let him return unto the LORD, and he will have mercy [upon him.]

The two readings on the verso have not been transcribed, but they are from Isaiah 60:1ff. and Isaiah 61:10ff, respectively.

The two readings on the verso have not been transcribed, but they are from Isaiah 60:1ff. and Isaiah 61:10ff, respectively.

Language: Latin.

Date: 14th c.

Title: Breviarium [fragment] : Feast of Epiphany.

Creator: Unidentified.

Place of creation: Northern Italy.

Physical description: Vellum, 1 leaf (2 p.) ; 25 x 31 cm.

Summary: Roman Catholic Church liturgy and ritual. Matins of the Feast of Epiphany (6 Jan.). In the Western Church, Epiphany commemorates the Journey of the three Magi to visit the infant Jesus. The first scripture reading (recto, right column) is Isaiah 55:1ff., the second (verso, left column) Isaiah 60:1ff., and the third (verso, right column) Isaiah 61:10ff., as specified in the Ordo Romanus XIIIa (see Andrieu, Michel. Les Ordines Romani du Haut Moyen Age, v.2. (Louvain: Specilegium Sacrum Lovaniense Administration, 1971): 487). Exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1940 ; exhibited at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, 1948.

Note: On recto, miniature of the visit of the Magi to Herod in the D of Deus ; two scenes depicted in lower margin : on left, the Baptism of Jesus, on right, the Temptation of Jesus in the Wilderness ; three-quarter border in red, blue, orange, green, brown and gold leaf, which includes two unidentified figures, two foxes(?) and two small roundels with depictions of a woman’s face (Mary’s?) ; verso contains two initials in red, blue and white with a partial border. Vellum damaged and crudely repaired, with some small loss of text to recto, verso badly damaged and faded, with some portions now nearly unreadable ; page appears to have been foreshortened from original height, though efforts were made to spare the illuminations. Gift of Eugene Gabarty (c. 1960?) ; formerly part of the collection of Adolf von Beckerath, Berlin.

- A Printed Breviary of the Use of the Benedictine Abbey of St Albans, St Albans, Hertfordshire, Published in 1532. (London, British Library, C.110.a.27); The Peterborough Antiphoner. (Cambridge, Magdalene College Ms F.4.10) [An Antiphoner of the 14th century from the Benedictine Abbey of St Peter, St Paul and St Andrew, Peterborough, Northamptonshire]; The Monastic Breviary of Hyde Abbey, Winchester (MS Rawlinson Liturg. e. 1.).

- A Printed Breviary of the Use of the Benedictine Abbey of St Albans, St Albans, Hertfordshire, Published in 1532. (London, British Library, C.110.a.27): f. 51r.