Jewish Resistance Collection

September 28, 2012

Description by Drew Flanagan, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in History

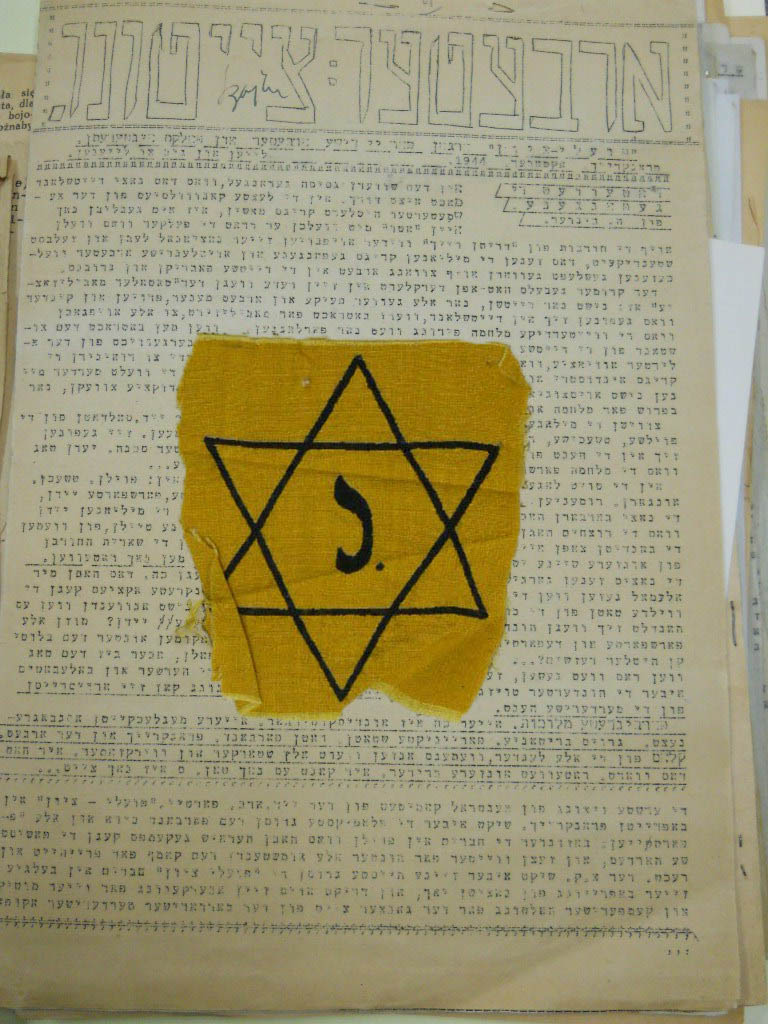

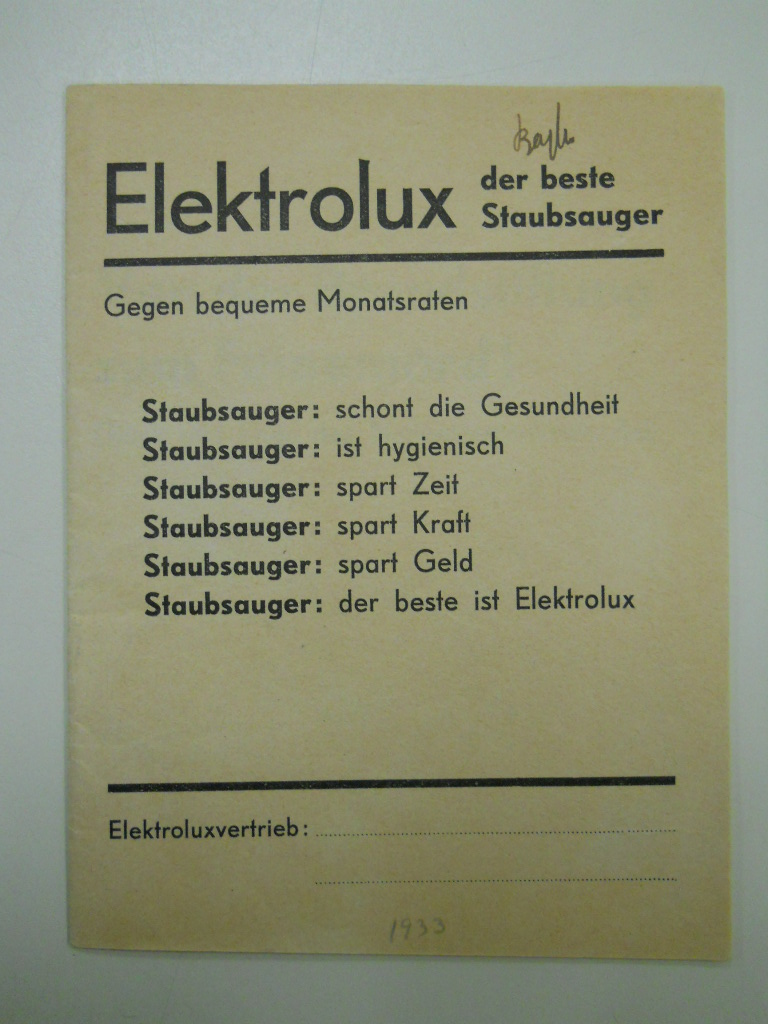

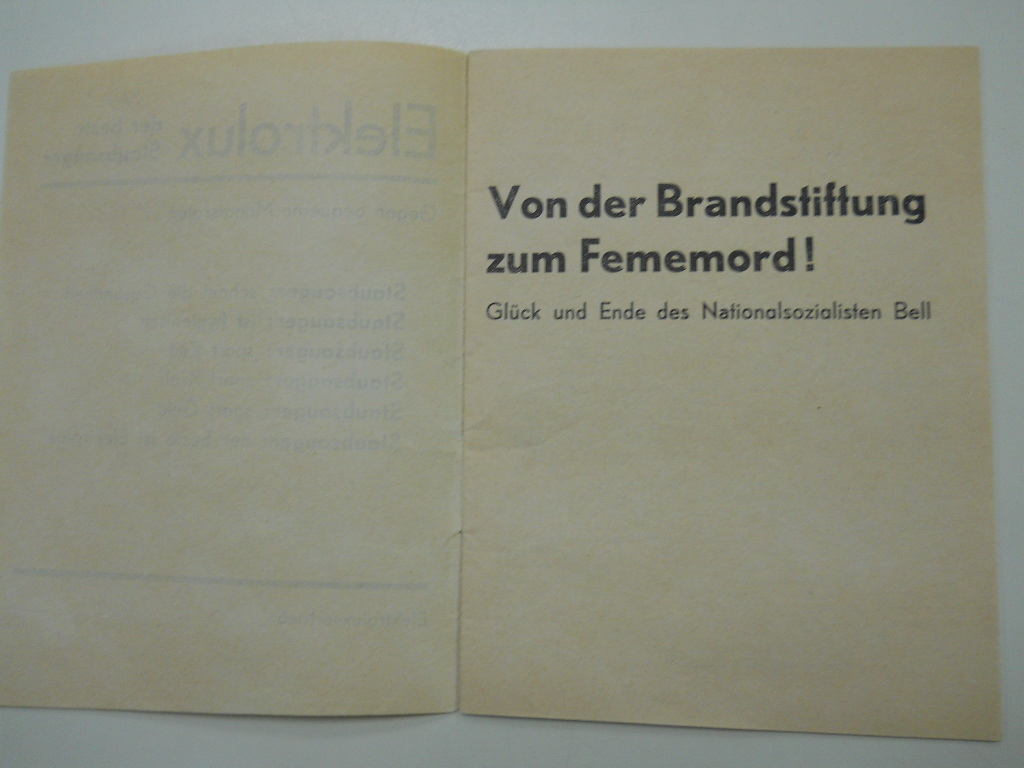

The Jewish Resistance Collection at the Brandeis University Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department contains 1.5 linear feet of propaganda material, individual testimonies, newsletters and other documents pertaining to Jewish resistance movements in Europe during World War II. This unprocessed collection contains documents in English, French, German, Polish, Dutch, Spanish, Hebrew, Yiddish and Italian. Documents include postwar reports on Nazi atrocities and assorted Nazi paraphernalia. Clandestine publications included in the collection deal with a range of issues, from major wartime events to the activities of Jewish resistance organizations. One such publication, a German antifascist pamphlet from 1933, is cleverly disguised as an owner’s manual for an Electrolux vacuum cleaner.

The Jewish Resistance Collection at the Brandeis University Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department contains 1.5 linear feet of propaganda material, individual testimonies, newsletters and other documents pertaining to Jewish resistance movements in Europe during World War II. This unprocessed collection contains documents in English, French, German, Polish, Dutch, Spanish, Hebrew, Yiddish and Italian. Documents include postwar reports on Nazi atrocities and assorted Nazi paraphernalia. Clandestine publications included in the collection deal with a range of issues, from major wartime events to the activities of Jewish resistance organizations. One such publication, a German antifascist pamphlet from 1933, is cleverly disguised as an owner’s manual for an Electrolux vacuum cleaner.

Outside: Vacuum Cleaner — the best is Electrolux!

Outside: Vacuum Cleaner — the best is Electrolux!

The collection also includes a sizeable collection of French Jewish resistance newspapers and propaganda distributed in Nice during the last year or so of the war. Somewhat out of step with its overall theme, the collection also includes several full-color magazines put out by the Bulgarian Communist Party in the 1970s.

As one of the central events of Jewish resistance under Nazi domination, the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising features prominently in a number of these publications. Differing interpretations of this event shed light on the experience of the war for Europe’s Jews in general, as well as the ideological differences within the Jewish resistance.

Inside: From Arson to Lynching — The Rise and Fall of the National Socialist Bell

Inside: From Arson to Lynching — The Rise and Fall of the National Socialist Bell

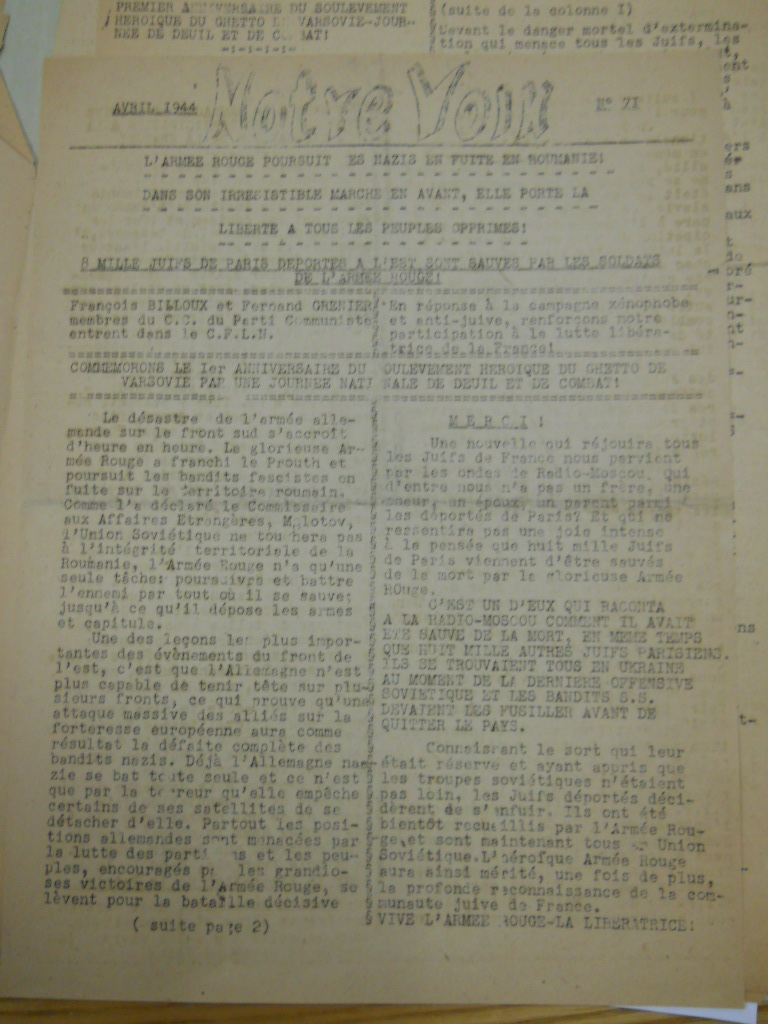

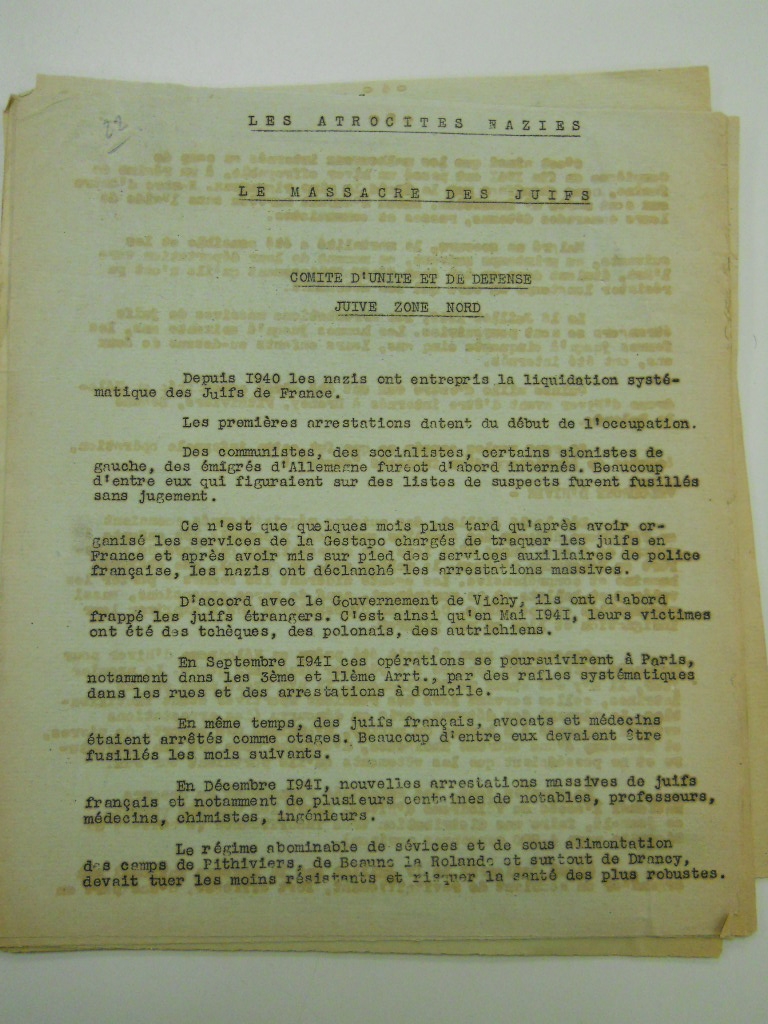

During the war, French Jewish resisters produced a range of documents that publicized and interpreted the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Collecting what information they could, they attempted to piece together the experiences of European Jews in the East and used those experiences to reflect on the meaning and value of Jewish resistance in Europe as a whole. This Spotlight focuses on two accounts. The first account is contained in the April 1944 issue of the Jewish communist resistance newspaper Notre Voix. The collection contains several issues of this paper as well as issues of several similar typewritten underground newspapers corresponding to different resistance organizations. Notre Voix provides an ideologically specific interpretation of the uprising and its consequences. In July 1944, a resistance group calling itself the Jewish Committee of Unity and Defense produced a longer, typewritten account of the uprising that places that event within the broader context of Nazi atrocities in Europe. The Jewish Committee’s interpretation of the event contains a very different interpretation of its meaning and importance. These two accounts reflect differing attempts to reconcile two contradictory images of the wartime Jew, as passive victim and as courageous resister.

Communist groups, perhaps unsurprisingly, tended to emphasize the role of (or fabricate a role for) the Soviet Union in the event. The April 1944 issue of Notre Voix contains an account of how, “inspired by the glorious example of their Soviet brothers, 35,000 Jews of Warsaw raised themselves, weapons in hand, against the ferocious enemy.”

Communist groups, perhaps unsurprisingly, tended to emphasize the role of (or fabricate a role for) the Soviet Union in the event. The April 1944 issue of Notre Voix contains an account of how, “inspired by the glorious example of their Soviet brothers, 35,000 Jews of Warsaw raised themselves, weapons in hand, against the ferocious enemy.”

The account is characterized by rather blatant factual inaccuracies, though this not especially surprising in a piece of propaganda. Most likely, 600-800 Jewish fighters engaged in the uprising, causing relatively minor material damage to the German army before being wiped out.[1] The article also tells how, although 30,000 were killed, “some thousands of Jews” managed to escape with their lives and join the Polish partisans. While some of the ghetto residents and fighters did manage to escape into the forest, this newsletter uses that fact to imply that acts of apparently hopeless armed resistance could have positive strategic value.

In addition to converting a small and hopeless rebellion into a major battle, Communist propaganda converted a ghetto population that might otherwise have appeared passive into a community of heroes. According to Notre Voix, the ghetto fighters died “not as fattened beasts but as heroic combatants. The Jews of Warsaw chose the glorious path of struggle […] it was not the hope of defeating that ferocious enemy that animated the heroic combatants of the Warsaw ghetto, but to make the Nazi bandits pay dearly for their lives, to defend their honor, to use all chances to save from extermination a part at least of the Jewish population.”[2]

It seems plausible that, in order to make armed resistance appear more hopeful and practical, these propagandists might have inflated both the casualties suffered by the Jewish resisters and the degree of military success they achieved. The rhetoric of this article reflects its multiple functions: as a recruitment tool for armed resistance, as a publicity broadside for international communism and as a tribute to the experience of the ghetto fighters.

Another document in the collection, put out by the “Jewish Committee of Unity and Defense” in July of 1944, contains a differing account of the same event that nonetheless reflects the essential tension between images of the Jew as resister and as victim. The document consists of a short description of Nazi war crimes in France, followed by a much longer appendix that describes the events of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in detail.

"Adama Czerniakow dziennik getta warszawskiego" wyd. Marian Fuks, PWN, Warszawa 1983, public domain.

"Adama Czerniakow dziennik getta warszawskiego" wyd. Marian Fuks, PWN, Warszawa 1983, public domain.

To begin with, its author interprets the causes of the uprising very differently from his communist counterpart. “In effect, the success of the Allies in North Africa reanimated their hope that life and liberty matter when we fight for them. They were also encouraged to revolt by the example of the Polish clandestine movement.”[3] The influence of the heroic Red Army is nowhere in sight in this account, while the often rabidly anticommunist Polish underground and the armed forces of the western allies takes its place. Unlike in the Notre Voix account, the sources for the information are clearly stated. In large part, the account is drawn from documents distributed by the Polish government in exile in London as well as information disseminated over the radio by the Polish underground radio operator “Swit.” Among other things, Swit reported that there were “300 dead and over 1000 injured” on the German side during the fighting, a much more plausible figure.[4]

Of particular interest is this document’s handling of a controversial individual: the head of Warsaw’s Jewish Council, Adam Czerniakow.

Here no attempt is made to deal with the implications of Jewish collaboration and instead Czerniakow is treated as purely a victim of the Germans. The document tells of his death as follows:

“In the evening of July 23, two functionaries of the German police visited again with Czerniakoff, who committed suicide a few moments after their departure. No one knew what had happened but it seems from the notes found after his death and a letter destined for his wife that he had decided to give his life when he realized that the Germans intended to change the first contingent of transfers to 10,000 and the daily contingent to 7,000. It is thus that the heroic mayor of the ghetto of Warsaw demonstrated in an indelible manner the horror and the indignation that he felt before the mass deportation of his people.”

The document’s author then claims that Czerniakow likely knew what would happen when his constituents arrived at Treblinka, but opines that his sacrifice was useless and largely overlooked at the time.[5]

In addition to the peculiarity of an interpretation of Czerniakow as a “heroic mayor” rather than a complex, tragic figure and a leading collaborator, the emphasis on his “useless” sacrifice serves as a preface to the description of the fighting in the ghetto that occurs soon after. After describing the fighting rather vaguely based on spotty information, the document concludes:

“Thus the Jewish population of Warsaw paid even more dearly than the Poles for its resistance to the Germans… but resistance was achieved in the silent protest of death with the extermination of the last Jew and the complete destruction of the ghetto itself.” [6]

This rather hopeless note contrasts sharply with the nearly fanatical dynamism of the communist account of the battle.

The piece finds a subtle and nuanced synthesis between the very real victimization experienced by the Jews of the ghetto and their equally real and courageous resistance activities.

“The atrocious persecutions of which they have been victims have demoralized and depressed the Jews of France. Others have had a more virile reaction. They are not resigned, they have not wanted to submit themselves to an implacable death, they have passed to the camp of men who are free and fighting, weapons in hand…”[7]

What at first appears to be a story of fruitless sacrifice is here revalorized as evidence of the “virility” and quality of Polish Jewry and an example to French Jews of how they ought to behave.

In these two examples, it can be seen how different opinions of the Jewish role in armed resistance to the Germans influenced two separate retellings of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising roughly one year after its occurrence. The communist interpretation of the events, aside from being manipulated to suit a narrative that emphasized the heroism of the Red Army, also presents a view of Jewish resistance that conveniently reconciles the Jew as victim and the Jew as resister. A small, hopeless symbolic uprising is presented as a mass uprising of the entire ghetto in which every resident died fighting, thus disguising the fact that many of the ghetto’s Jews did not or could not fight. Meanwhile, the version of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising told by the Jewish Committee of Unity and Defense is more factually accurate and provides a more positive impression of the moral strength of the Jewish people, presenting even the head of Warsaw’s Jewish Council as a hero of the resistance. This telling privileges the symbolic value of acts of resistance, awarding Czerniakow and the ghetto fighters alike the title of hero for protesting with “the silence of death,” even while admitting the strategic uselessness of their gestures. In each case, through reflecting on the resistance of Jews both in France and in Poland, French Jewish resistance organizations began to work toward retrospective visions of the Jewish experience of World War II that would be politically useful and emotionally acceptable for their members—retrospective visions that could take into account both the worst humiliations of the Holocaust and the greatest acts of heroism undertaken by Jewish resistance fighters.

In these two examples, it can be seen how different opinions of the Jewish role in armed resistance to the Germans influenced two separate retellings of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising roughly one year after its occurrence. The communist interpretation of the events, aside from being manipulated to suit a narrative that emphasized the heroism of the Red Army, also presents a view of Jewish resistance that conveniently reconciles the Jew as victim and the Jew as resister. A small, hopeless symbolic uprising is presented as a mass uprising of the entire ghetto in which every resident died fighting, thus disguising the fact that many of the ghetto’s Jews did not or could not fight. Meanwhile, the version of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising told by the Jewish Committee of Unity and Defense is more factually accurate and provides a more positive impression of the moral strength of the Jewish people, presenting even the head of Warsaw’s Jewish Council as a hero of the resistance. This telling privileges the symbolic value of acts of resistance, awarding Czerniakow and the ghetto fighters alike the title of hero for protesting with “the silence of death,” even while admitting the strategic uselessness of their gestures. In each case, through reflecting on the resistance of Jews both in France and in Poland, French Jewish resistance organizations began to work toward retrospective visions of the Jewish experience of World War II that would be politically useful and emotionally acceptable for their members—retrospective visions that could take into account both the worst humiliations of the Holocaust and the greatest acts of heroism undertaken by Jewish resistance fighters.

Notes

- Alfred Katz, Poland’s Ghettos at War (New York: Twayne Publishers, inc., 1970), 80.

- Francois Billoux, “Notre Voix #71”, April 1944, Jewish Resistance Collection, unprocessed, Robert D. Farber University Archives, Brandeis University.

- Jewish Committee of Unity and Defense, Northern Zone, “Nazi Atrocities: The Massacre of Jews (with appendix on the Warsaw ghetto)”, July 1944, 11, Jewish Resistance Collection, unprocessed, Robert D. Farber University Archives, Brandeis University.

- Ibid., 12.

- Ibid., 5.

- Ibid., appendix 12.

- Ibid., 7.