Arthur Laurents Correspondence

Any Shakespeare student or fan of musicals will tell you that the tale behind “West Side Story” is “Romeo and Juliet”—but there is another story behind the creation of the award-winning musical that is less well known. The creators of the musical—Arthur Laurents, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim and Jerome Robbins—did not always agree about the direction the show should be taking. Correspondence in the Arthur Laurents collection at Brandeis reveals a backdrop of argument, reconciliation and frequent changes to the musical.

Arthur Laurents (1917-2011) was a playwright, novelist and director; while he was perhaps best known for “West Side Story,” for which he wrote the book, Laurents was celebrated for many successful projects for stage and film. He wrote a memoir of his work and life in 2000, entitled “Original Story By,” in which he discussed his blacklisting from Hollywood during McCarthyism, his homosexuality and his success and failures on Broadway.

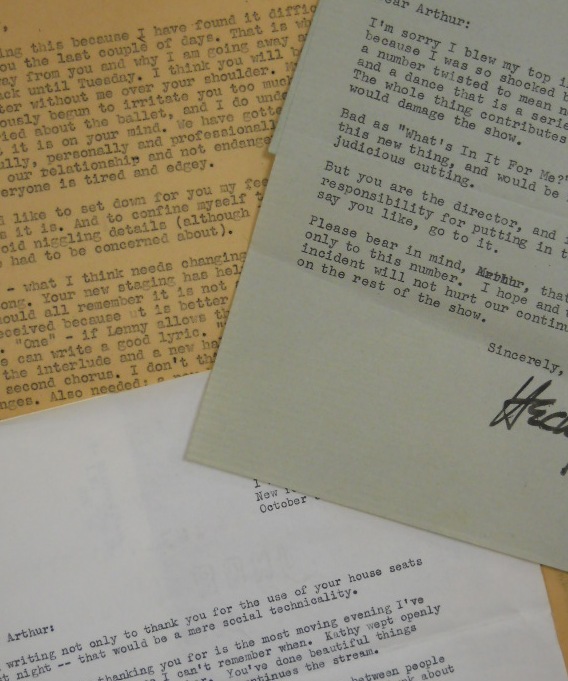

The Arthur Laurents collection at Brandeis consists primarily of typescripts of several plays and screenplays, including annotated typescripts of “West Side Story” and other productions. The folder of correspondence in the collection relates mainly to the development of “West Side Story” and “I Can Get it for You Wholesale,” and includes letters from Irving Berlin, Jerome Robbins and Harold Rome, among others involved with the two shows. The correspondence demonstrates a frequent back-and-forth between the principal creative agents, including disagreements over particular characters and scenes as well as larger issues of creative control.

The Arthur Laurents collection at Brandeis consists primarily of typescripts of several plays and screenplays, including annotated typescripts of “West Side Story” and other productions. The folder of correspondence in the collection relates mainly to the development of “West Side Story” and “I Can Get it for You Wholesale,” and includes letters from Irving Berlin, Jerome Robbins and Harold Rome, among others involved with the two shows. The correspondence demonstrates a frequent back-and-forth between the principal creative agents, including disagreements over particular characters and scenes as well as larger issues of creative control.

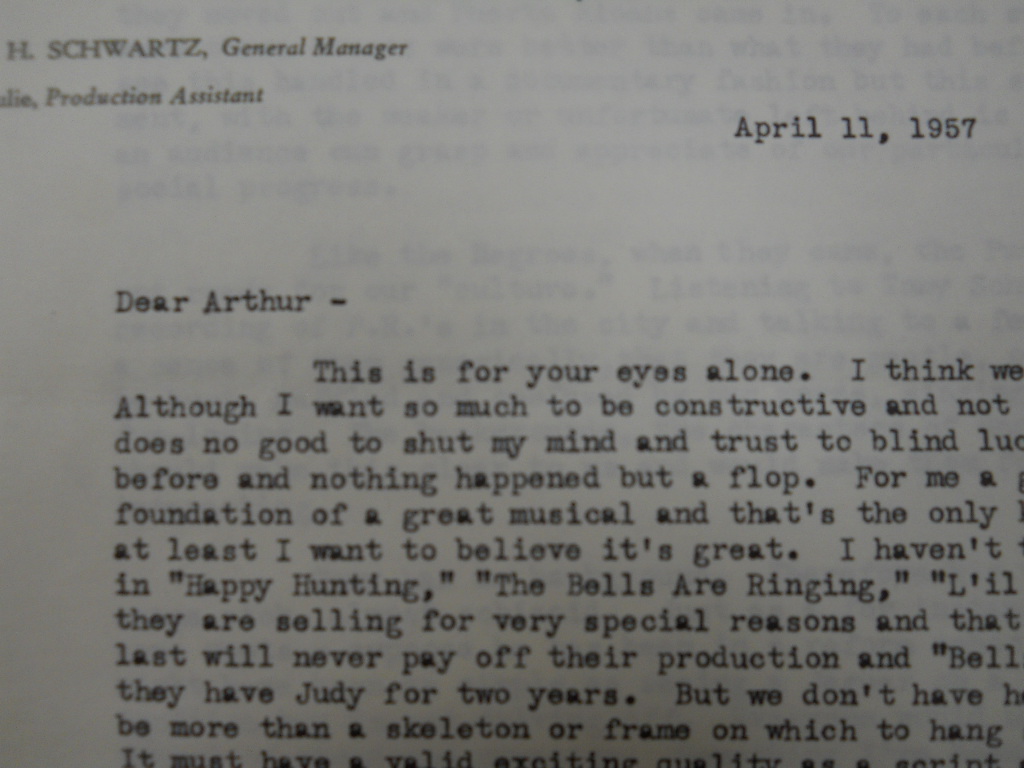

For example, Cheryl Crawford, who had been the producer for the show until she dropped it shortly before rehearsals began for its Broadway debut in September of 1957, voices doubts about the production in a letter to Laurents in April of that year: "I think we are in trouble. Although I want so much to be constructive and not destructive, it does no good to shut my mind and trust to blind luck." She outlines a number of problems with the plans for the show, including the critique that “The story at present has no real depth or urgency.”

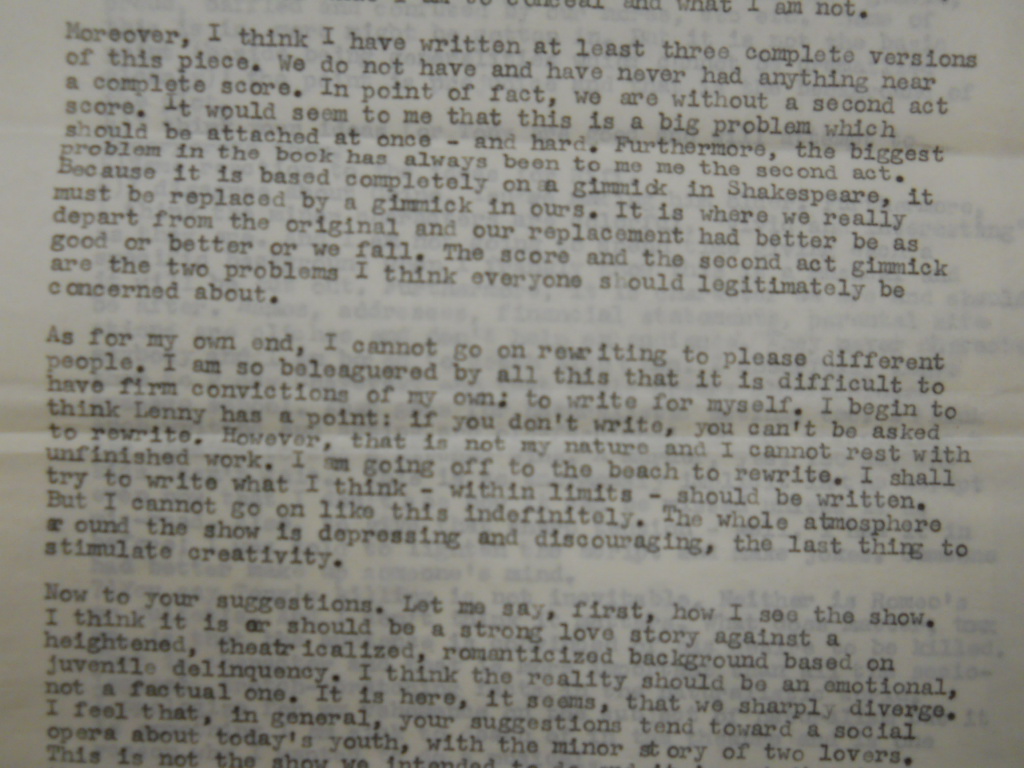

In a letter back to Crawford, Laurents addresses her concerns; some he agrees with, some not: "I apologize for my vehemence on the subject of naturalism but it is something I am sick to death of in the theatre and is one reason why I wanted to do a musical." He also writes: “…the biggest problem in the book has always been to me the second act. Because it is based completely on a gimmick in Shakespeare, it must be replaced by a gimmick in ours. It is where we really depart from the original and our replacement had better be as good or better or we fall.” It is clear that Laurents has heard critiques from various sides, telling Crawford that “as for my own end, I cannot go on rewriting to please different people.”

In a letter back to Crawford, Laurents addresses her concerns; some he agrees with, some not: "I apologize for my vehemence on the subject of naturalism but it is something I am sick to death of in the theatre and is one reason why I wanted to do a musical." He also writes: “…the biggest problem in the book has always been to me the second act. Because it is based completely on a gimmick in Shakespeare, it must be replaced by a gimmick in ours. It is where we really depart from the original and our replacement had better be as good or better or we fall.” It is clear that Laurents has heard critiques from various sides, telling Crawford that “as for my own end, I cannot go on rewriting to please different people.”

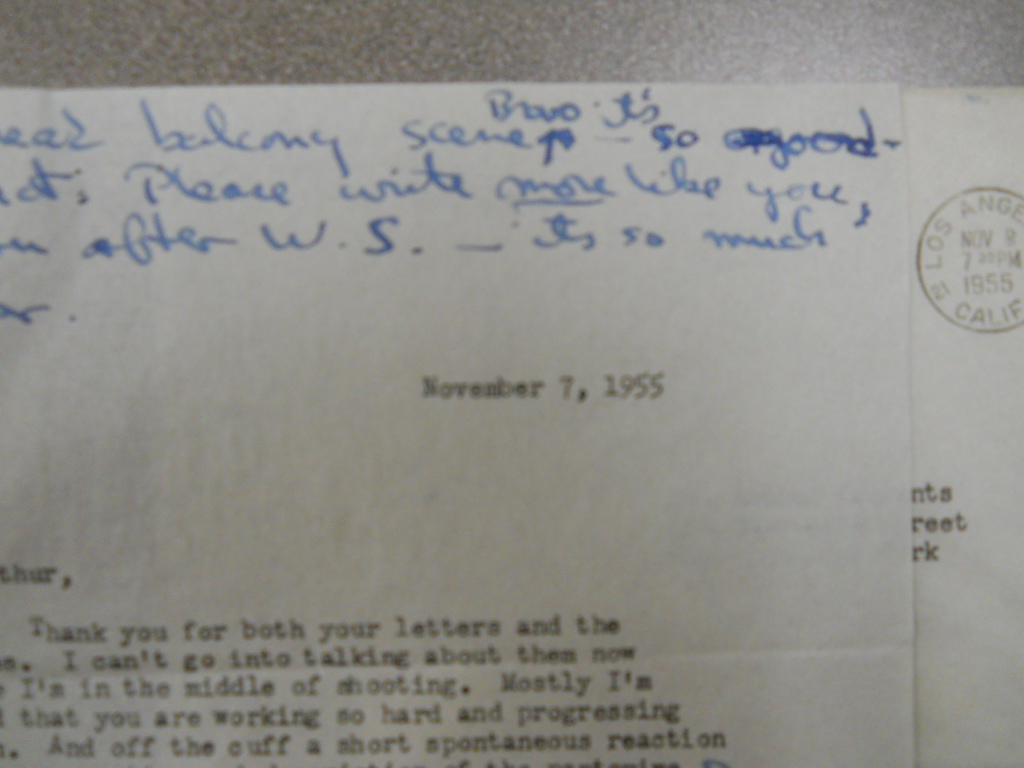

Not all of the letters are disapproving. Some of the richest correspondence comes from Jerome Robbins, the director and choreographer of the show, who writes in a handwritten postscript to his letter of November 7, 1955: "Just read balcony scene—Bravo—it's so good...." A few weeks before, Robbins had written a letter in which he reassures Laurents that he feels hopeful about the show as a whole: “…before I tell you my objections I want you to know that I think it’s a hell of a good job and very much on the right track, and that these differences are incidental to the larger wonderful job you are both doing.”

Not all of the letters are disapproving. Some of the richest correspondence comes from Jerome Robbins, the director and choreographer of the show, who writes in a handwritten postscript to his letter of November 7, 1955: "Just read balcony scene—Bravo—it's so good...." A few weeks before, Robbins had written a letter in which he reassures Laurents that he feels hopeful about the show as a whole: “…before I tell you my objections I want you to know that I think it’s a hell of a good job and very much on the right track, and that these differences are incidental to the larger wonderful job you are both doing.”

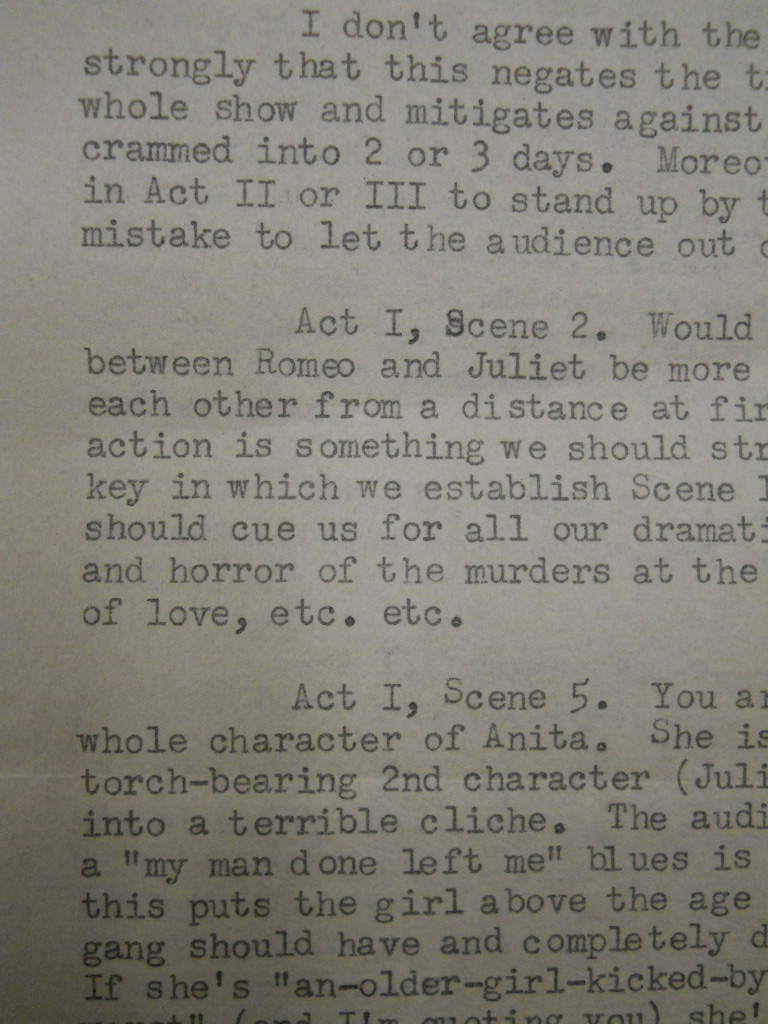

In that same letter, Robbins provides pointed notes on about a dozen scenes in the outline of the play, such as: "Act I, Scene 5. You are away off the track with the whole character of Anita. She is the typical downbeat blues torch-bearing 2nd character (Julie of SHOWBOAT, etc) and falls into a terrible cliche. The audience will know that somewhere a ‘my man done left me’ blues is coming up for her."

In that same letter, Robbins provides pointed notes on about a dozen scenes in the outline of the play, such as: "Act I, Scene 5. You are away off the track with the whole character of Anita. She is the typical downbeat blues torch-bearing 2nd character (Julie of SHOWBOAT, etc) and falls into a terrible cliche. The audience will know that somewhere a ‘my man done left me’ blues is coming up for her."

About a week later, Robbins points out what he finds to be the strongest parts of the work-in-progress, and his theory as to why: “I like best the sections in which you have gone on your own path, writing in your own style with your own characters and imagination. Least successful are the sections in which I sense the intimidation of Shakespeare standing behind you.”

About a week later, Robbins points out what he finds to be the strongest parts of the work-in-progress, and his theory as to why: “I like best the sections in which you have gone on your own path, writing in your own style with your own characters and imagination. Least successful are the sections in which I sense the intimidation of Shakespeare standing behind you.”

A letter from Robbins written on November 21, 1955, is evidently a response to an exchange with Laurents discussing some of his comments. “Thank you for the letter and the scene. As for your letter and your reaction to my criticism I have to confess that mine also is oh, dear! I guess for the same reasons as yours.” This letter outlines both positives and negatives in the script Robbins has read, including more of his opinion on the character of Anita: “I still don’t see what the hell you’re driving at with Anita’s character except to justify the appearance of a friend of yours in the show. I don’t agree at all about this age girl going with this set.”

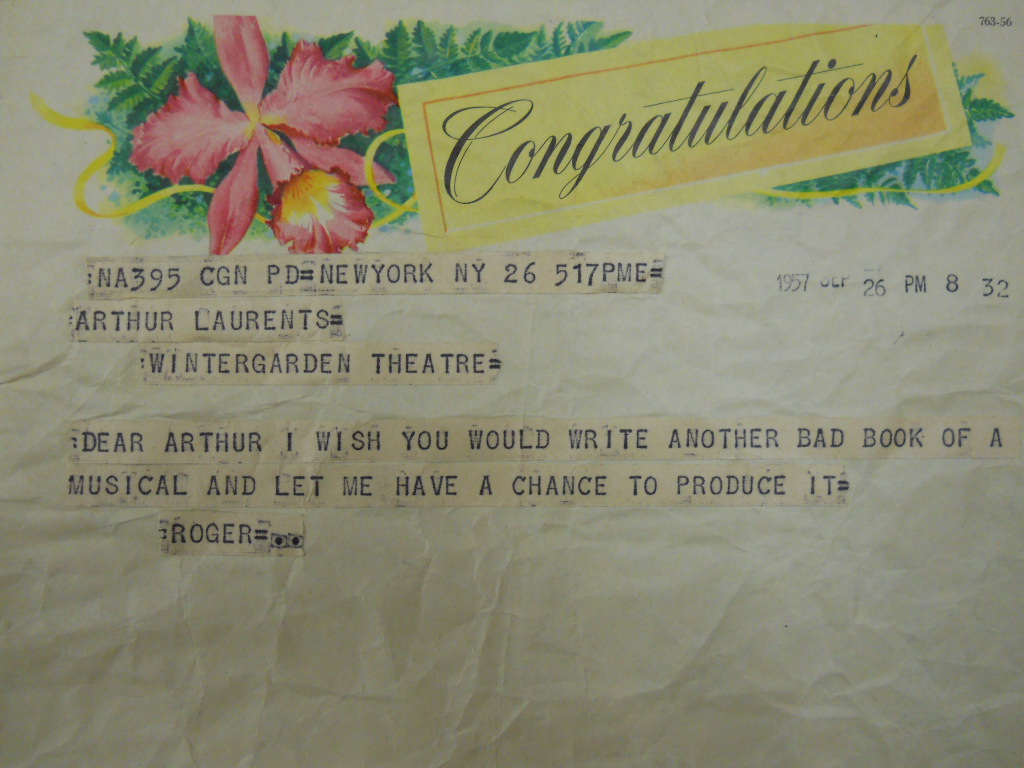

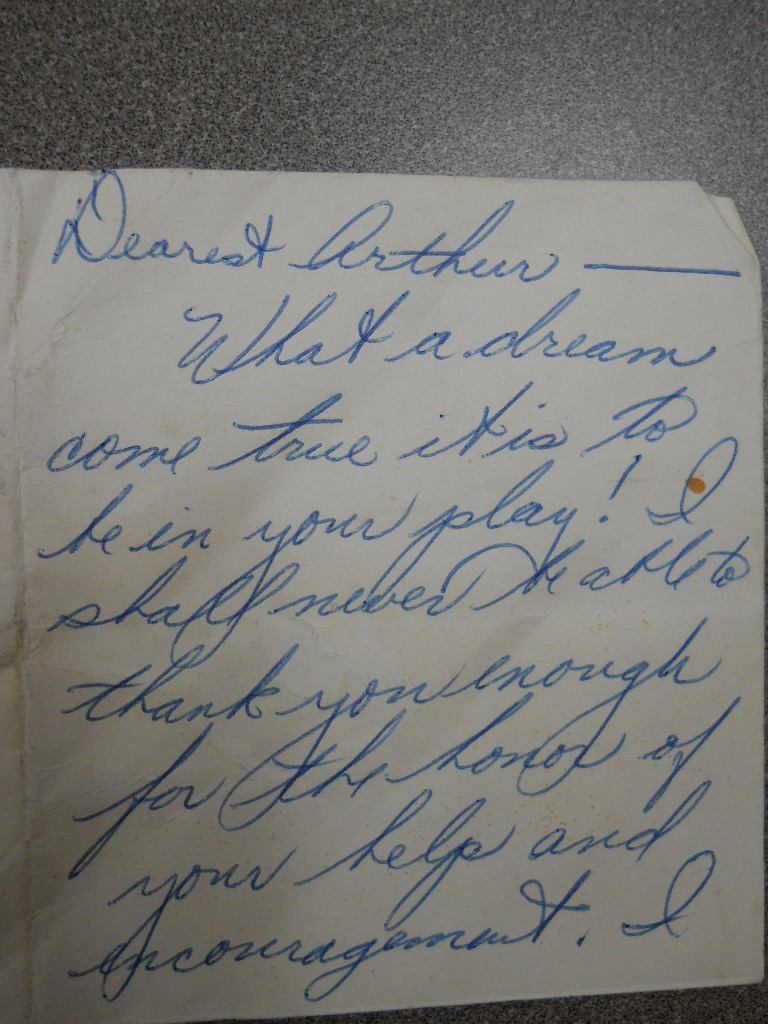

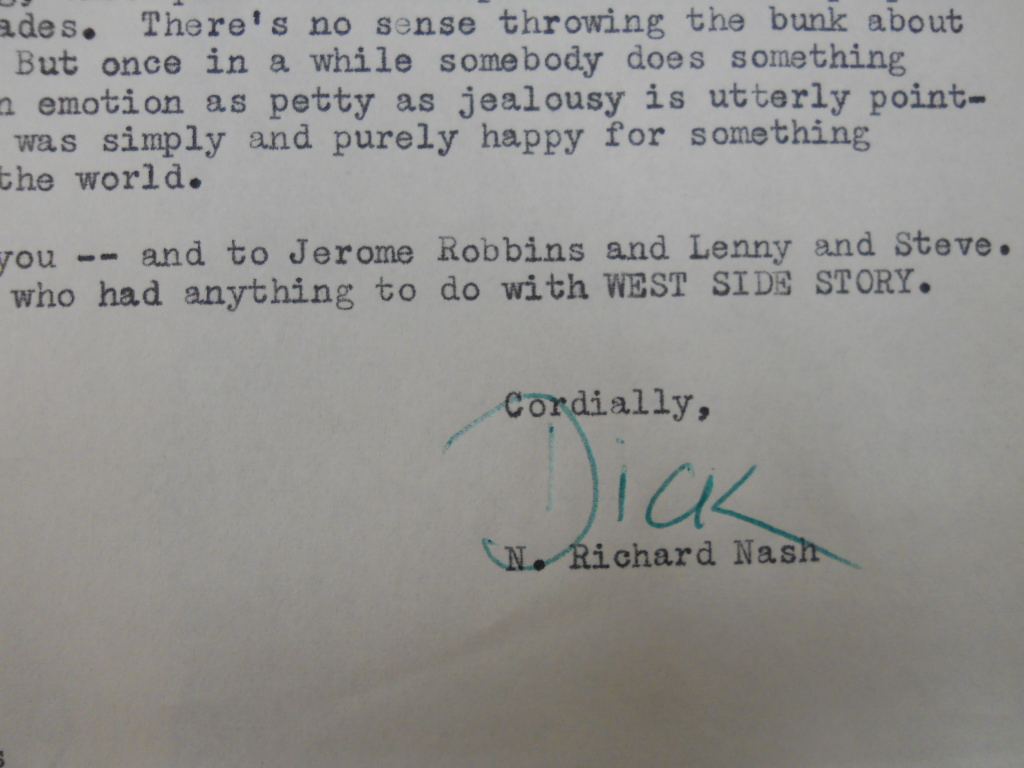

After the show opened, enthusiastic letters came in. Richard Nash, also a Broadway writer, wrote a gracious letter to Laurents the day after he saw “West Side Story,” on October 31, 1957: “…once in a while somebody does something so beautiful that an emotion as petty as jealousy is utterly pointless. Last night I was simply and purely happy for something newly beautiful in the world.” In September of 1957, a telegram came from Roger (presumably Roger Stevens, the theatre producer) to say "Dear Arthur I wish you would write another bad book of a musical and let me have a chance to produce it." A card signed “Maria” (from the show’s star, Carol Lawrence) gushes, "What a dream come true it is to be in your play!"

After the show opened, enthusiastic letters came in. Richard Nash, also a Broadway writer, wrote a gracious letter to Laurents the day after he saw “West Side Story,” on October 31, 1957: “…once in a while somebody does something so beautiful that an emotion as petty as jealousy is utterly pointless. Last night I was simply and purely happy for something newly beautiful in the world.” In September of 1957, a telegram came from Roger (presumably Roger Stevens, the theatre producer) to say "Dear Arthur I wish you would write another bad book of a musical and let me have a chance to produce it." A card signed “Maria” (from the show’s star, Carol Lawrence) gushes, "What a dream come true it is to be in your play!"

After “West Side Story”—nominated for a Tony award for best musical—Laurents wrote several other successful musicals and was also active as a director. Correspondence related to the 1962 musical “I Can Get It for You Wholesale,” with music and lyrics by Harold Rome and direction by Laurents (and with a cast including a young Barbra Streisand in her Broadway debut), reveals another round of contentious collaboration. Harold Rome wrote a letter to Laurents on March 5, 1962, a couple of weeks before the opening, indicating an angry episode: “I’m sorry I blew my top in the theatre. I lost control because I was so shocked by what I saw on the stage—a number twisted to mean nothing—that goes nowhere and a dance that is a series of meaningless gymnastics.” But Rome strikes a conciliatory tone (“you are the director…”) and expresses hope that they can continue to cooperate.

After “West Side Story”—nominated for a Tony award for best musical—Laurents wrote several other successful musicals and was also active as a director. Correspondence related to the 1962 musical “I Can Get It for You Wholesale,” with music and lyrics by Harold Rome and direction by Laurents (and with a cast including a young Barbra Streisand in her Broadway debut), reveals another round of contentious collaboration. Harold Rome wrote a letter to Laurents on March 5, 1962, a couple of weeks before the opening, indicating an angry episode: “I’m sorry I blew my top in the theatre. I lost control because I was so shocked by what I saw on the stage—a number twisted to mean nothing—that goes nowhere and a dance that is a series of meaningless gymnastics.” But Rome strikes a conciliatory tone (“you are the director…”) and expresses hope that they can continue to cooperate.

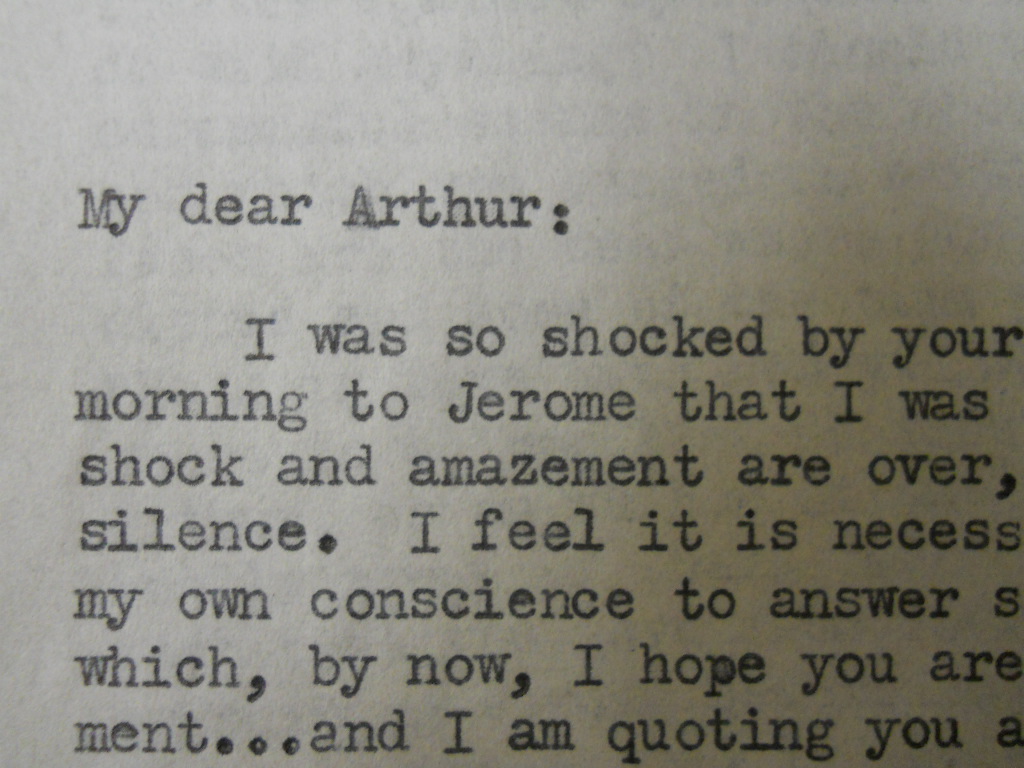

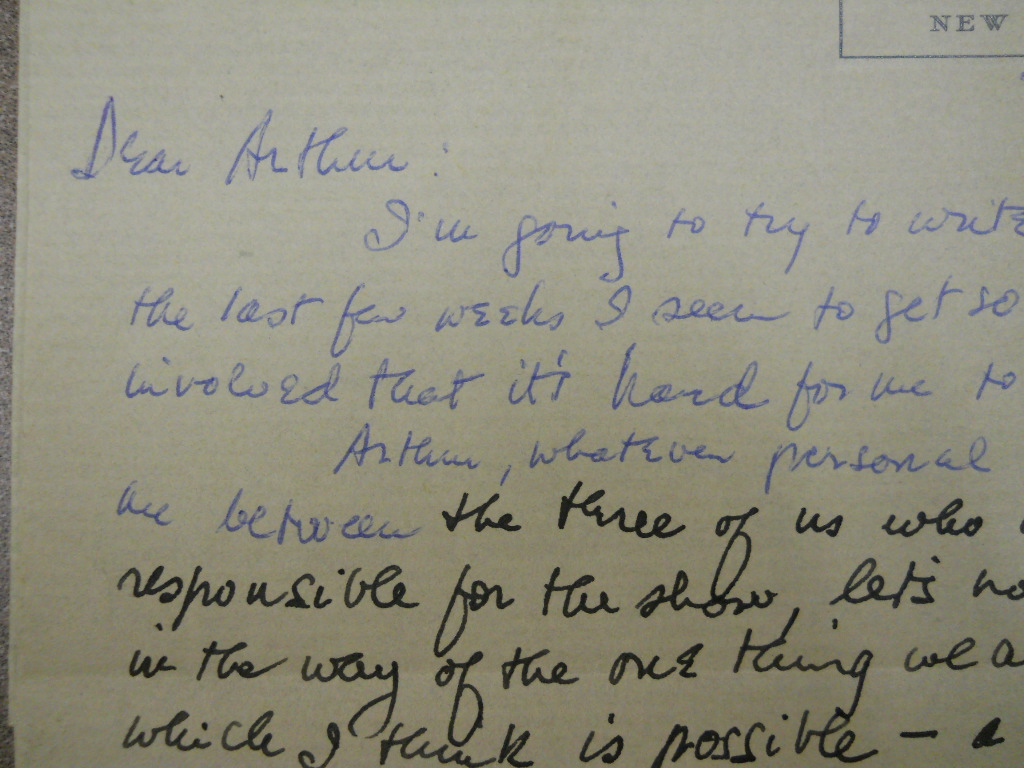

A few days later, another letter from Rome responds to another altercation he has evidently had with Laurents. Rome allies with Jerome Weidman, who wrote the musical’s book; the letter opens with: “I was so shocked by your statement on the phone yesterday morning to Jerome that I was literally speechless. Now that the shock and amazement are over, I feel I cannot let it go by in silence.” He goes on to elaborate on the problems he is having working with Laurents. A carbon of a letter from Laurents to Jerome Weidman was also written in the aftermath of an argument, with specific examples of what is wrong with the show. “I think you will be able to work better without me over your shoulder. My “nagging” has obviously begun to irritate you too much.” Laurents strikes a conciliatory tone here too: “Oh, there I go—telling you things you know. Well, you will be rid of me for several days! That’s probably the nicest and happiest thing I can say.”

A few days later, another letter from Rome responds to another altercation he has evidently had with Laurents. Rome allies with Jerome Weidman, who wrote the musical’s book; the letter opens with: “I was so shocked by your statement on the phone yesterday morning to Jerome that I was literally speechless. Now that the shock and amazement are over, I feel I cannot let it go by in silence.” He goes on to elaborate on the problems he is having working with Laurents. A carbon of a letter from Laurents to Jerome Weidman was also written in the aftermath of an argument, with specific examples of what is wrong with the show. “I think you will be able to work better without me over your shoulder. My “nagging” has obviously begun to irritate you too much.” Laurents strikes a conciliatory tone here too: “Oh, there I go—telling you things you know. Well, you will be rid of me for several days! That’s probably the nicest and happiest thing I can say.”

The correspondence in the Arthur Laurents collection about these two Broadway shows reveals working relationships obviously fraught with disagreement. The specific and substantive changes proposed by various correspondents to each production is fascinating in retrospect. Through their correspondence, the various personalities involved clash, reconcile and attempt to navigate a way to collaborate, opening an interesting window into the sometimes messy process behind the creation of iconic Broadway productions.

The correspondence in the Arthur Laurents collection about these two Broadway shows reveals working relationships obviously fraught with disagreement. The specific and substantive changes proposed by various correspondents to each production is fascinating in retrospect. Through their correspondence, the various personalities involved clash, reconcile and attempt to navigate a way to collaborate, opening an interesting window into the sometimes messy process behind the creation of iconic Broadway productions.