Leo Frank Trial Collection, 1909-1961

October 29, 2009

The Leo Frank Trial Collection at Brandeis University documents one of the most notorious capital-punishment cases in early 20th-century America. Leo Frank, a pencil-factory superintendent in Atlanta, Georgia, and a northern Jew, was at the center of a murder trial and lynching that continues to reverberate almost 95 years later.

Frank was born in Texas in 1884 but spent his formative years in Brooklyn. He attended Cornell University, graduating with an engineering degree in 1906, and married Lucille Selig, a Georgia native, four years later. The Franks lived in Atlanta, where Leo was the superintendent of the National Pencil Factory and active in B’nai Brith.

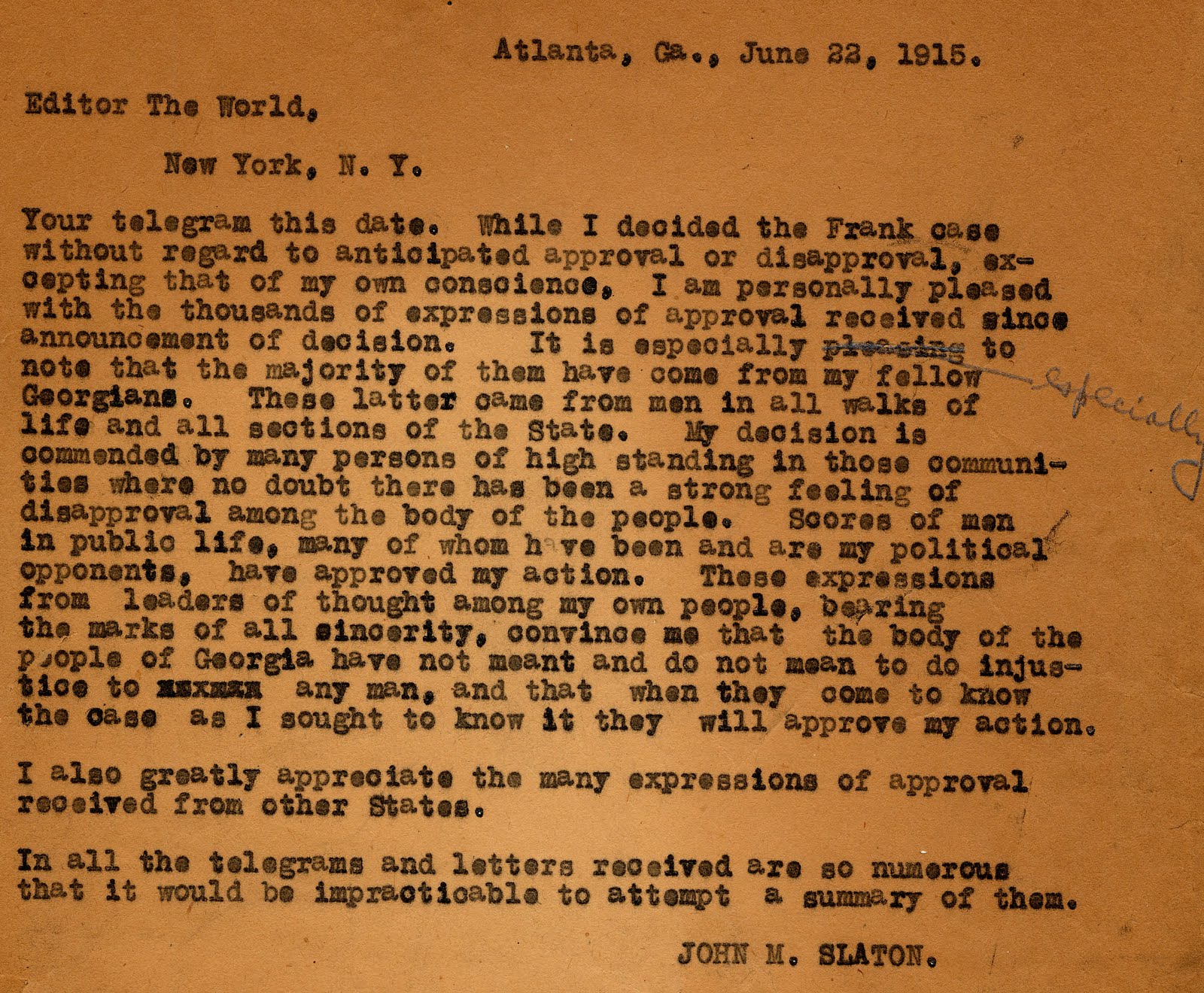

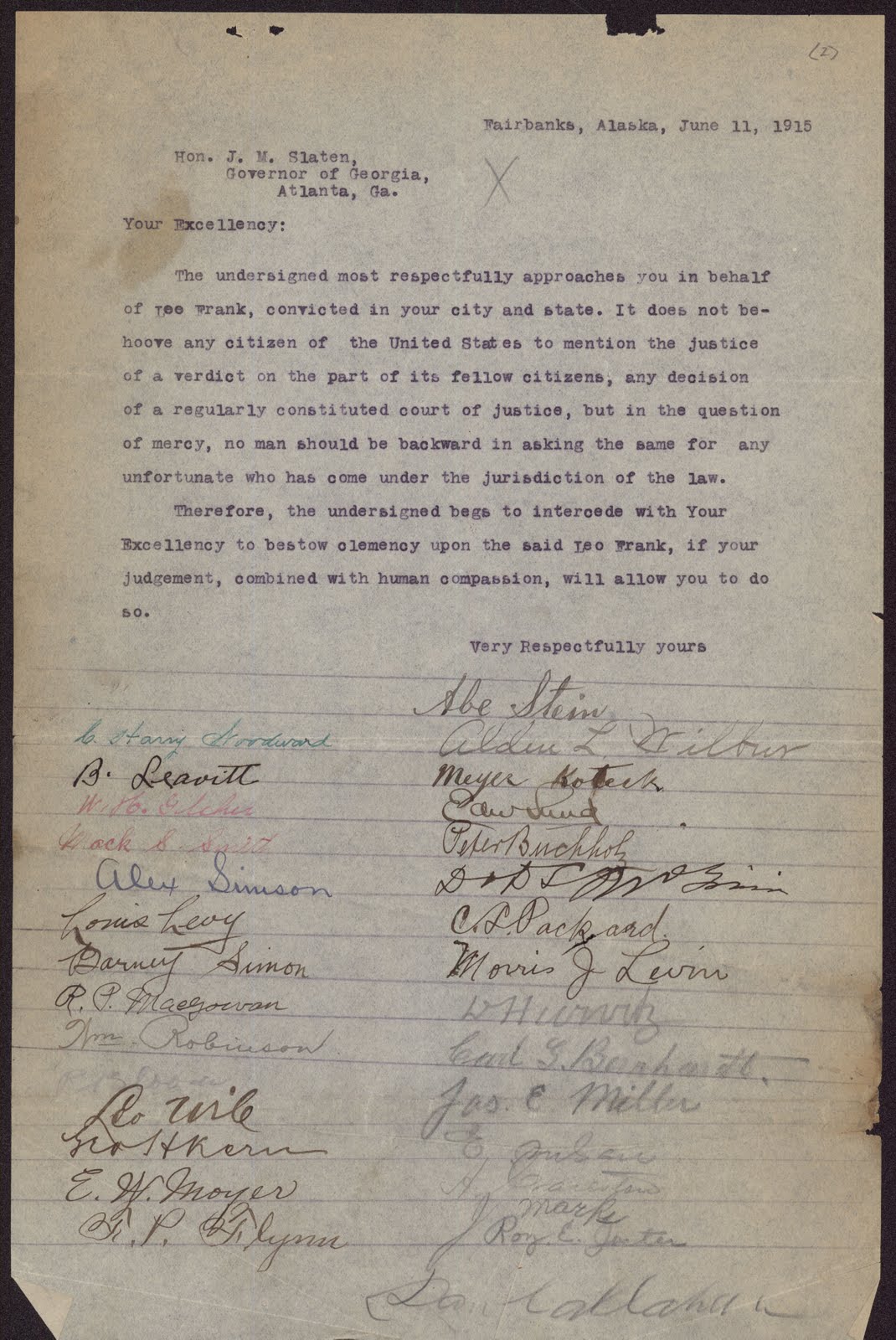

In April of 1913, a young employee of the National Pencil Factory named Mary Phagan was found murdered. Frank was accused and convicted based on circumstantial evidence; the trial was widely considered a mockery of justice, with crowds shouting “hang the Jew” outside the courtroom. Frank was sentenced to death. While he was in prison, new evidence came to light; in response to this and to widespread public outcry and petitioning (represented in the collection at Brandeis), Governor John Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence to life in prison. Slaton’s decision instigated a mob—composed in part of prominent individuals including a former state governor—to kidnap Frank from prison and lynch him on August 17, 1915. Commemorative postcards were printed displaying Frank’s hanging body. The events surrounding the Leo Frank case were instrumental in the founding of the Anti-Defamation League; they also spurred the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan.

In April of 1913, a young employee of the National Pencil Factory named Mary Phagan was found murdered. Frank was accused and convicted based on circumstantial evidence; the trial was widely considered a mockery of justice, with crowds shouting “hang the Jew” outside the courtroom. Frank was sentenced to death. While he was in prison, new evidence came to light; in response to this and to widespread public outcry and petitioning (represented in the collection at Brandeis), Governor John Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence to life in prison. Slaton’s decision instigated a mob—composed in part of prominent individuals including a former state governor—to kidnap Frank from prison and lynch him on August 17, 1915. Commemorative postcards were printed displaying Frank’s hanging body. The events surrounding the Leo Frank case were instrumental in the founding of the Anti-Defamation League; they also spurred the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan.

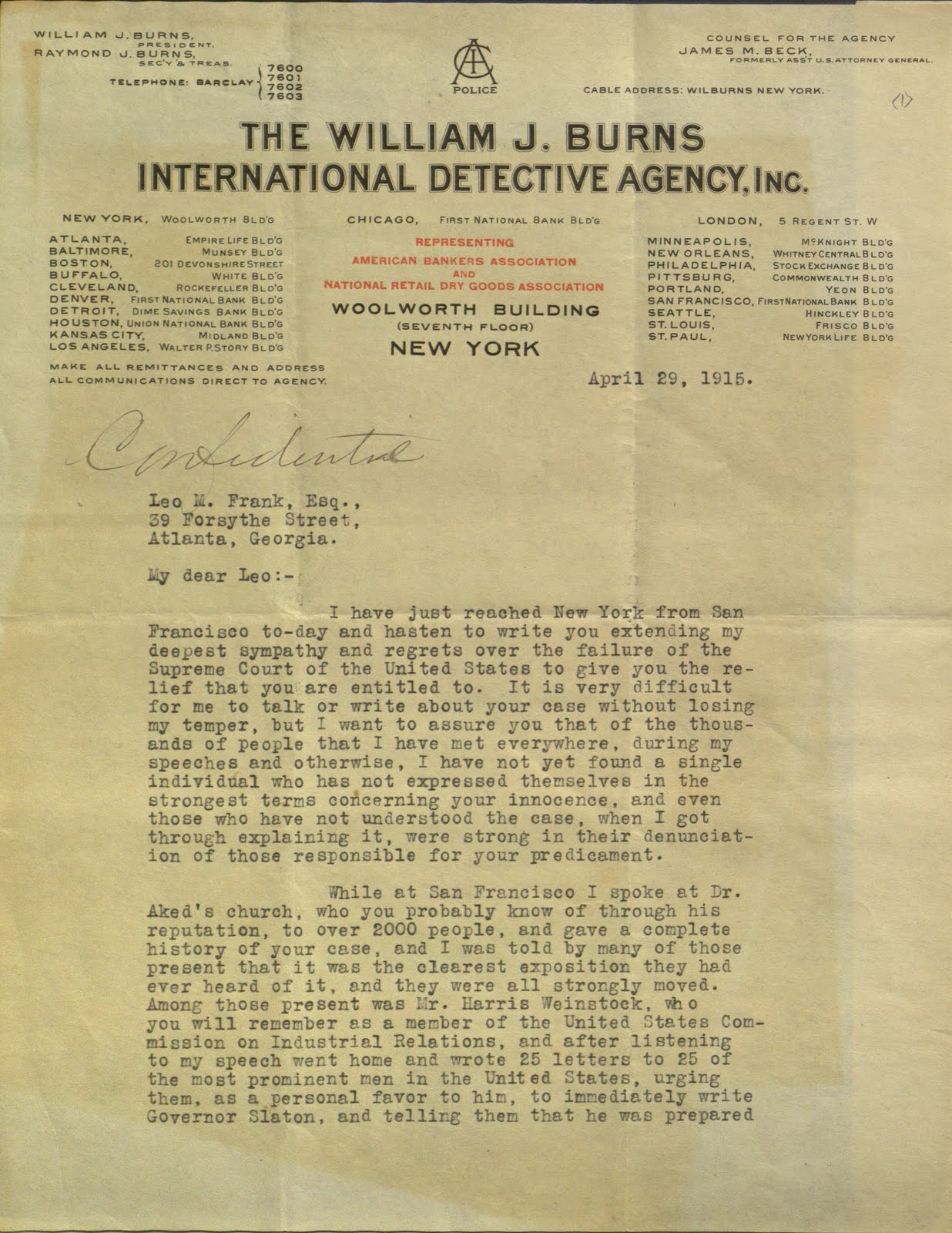

The Leo Frank Trial Collection at Brandeis includes letters written by Leo Frank, the majority of them from prison, as well as correspondence to and from his wife, Lucille, and correspondence to and from Governor Slaton, Frank’s lawyer, and others. The collection also contains related articles, pamphlets and legal documents. Within these categories are letters of support, death threats to Governor Slaton, petitions on behalf of Frank, news clippings, thank-you letters from Lucille Frank to various supporters and anti-Semitic as well as pro-Frank publications.

The Leo Frank Trial Collection at Brandeis includes letters written by Leo Frank, the majority of them from prison, as well as correspondence to and from his wife, Lucille, and correspondence to and from Governor Slaton, Frank’s lawyer, and others. The collection also contains related articles, pamphlets and legal documents. Within these categories are letters of support, death threats to Governor Slaton, petitions on behalf of Frank, news clippings, thank-you letters from Lucille Frank to various supporters and anti-Semitic as well as pro-Frank publications.

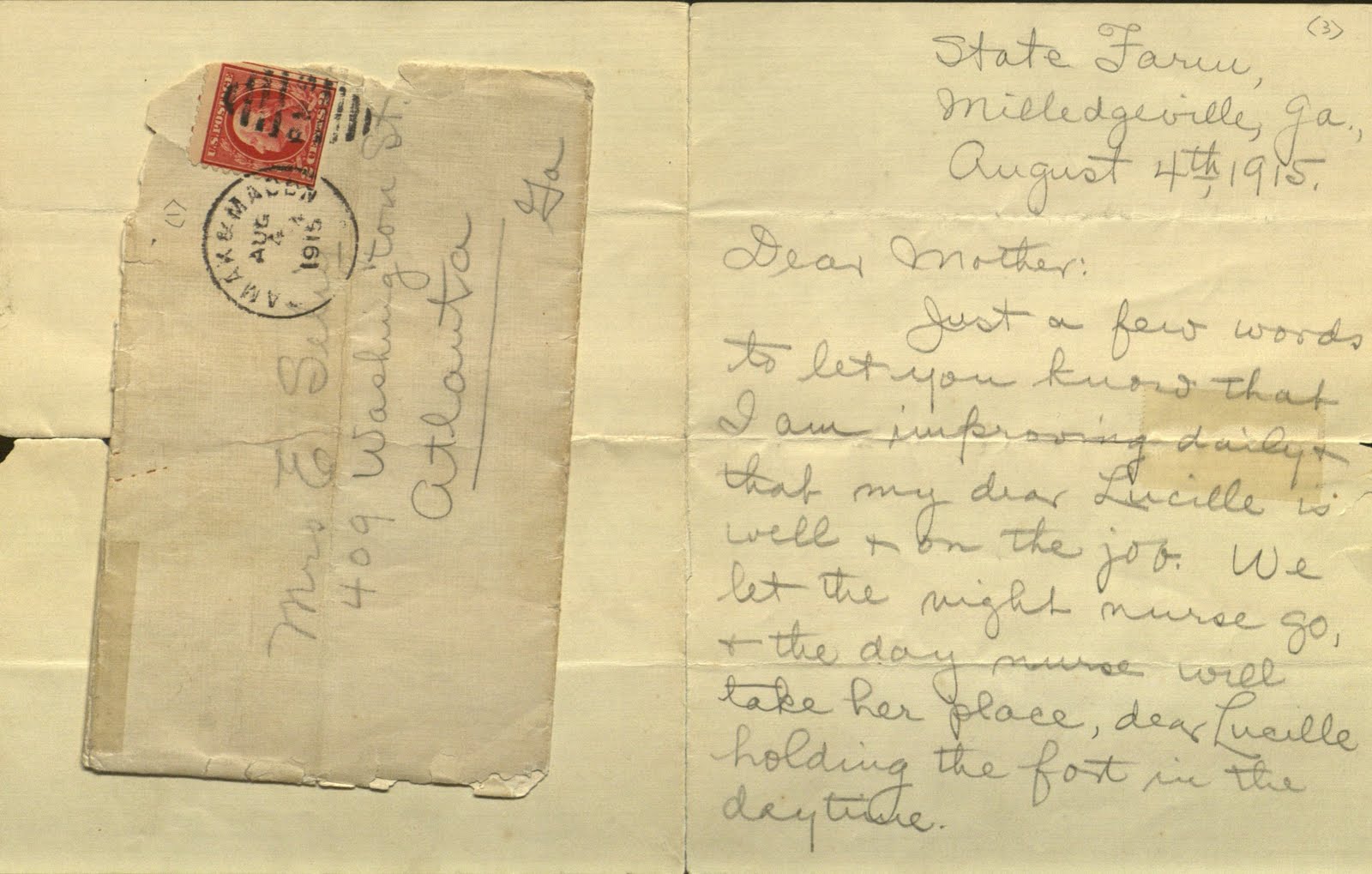

At the heart of the collection is the correspondence. Many of Leo Frank’s letters to his wife describe the day-to-day needs and doings of prison life, the state of his health and his affection for her. In the last letter contained in the collection from Frank, he writes to his mother-in-law after an attempt on his life was made by another inmate: “I hope you did not yesterday or today hear the rumor I heard—viz: that I was dead. I want to firmly and decisively deny that rumor. I am alive by a big majority.” This letter was written on August 4, 1915, two weeks before Frank was murdered.

At the heart of the collection is the correspondence. Many of Leo Frank’s letters to his wife describe the day-to-day needs and doings of prison life, the state of his health and his affection for her. In the last letter contained in the collection from Frank, he writes to his mother-in-law after an attempt on his life was made by another inmate: “I hope you did not yesterday or today hear the rumor I heard—viz: that I was dead. I want to firmly and decisively deny that rumor. I am alive by a big majority.” This letter was written on August 4, 1915, two weeks before Frank was murdered.

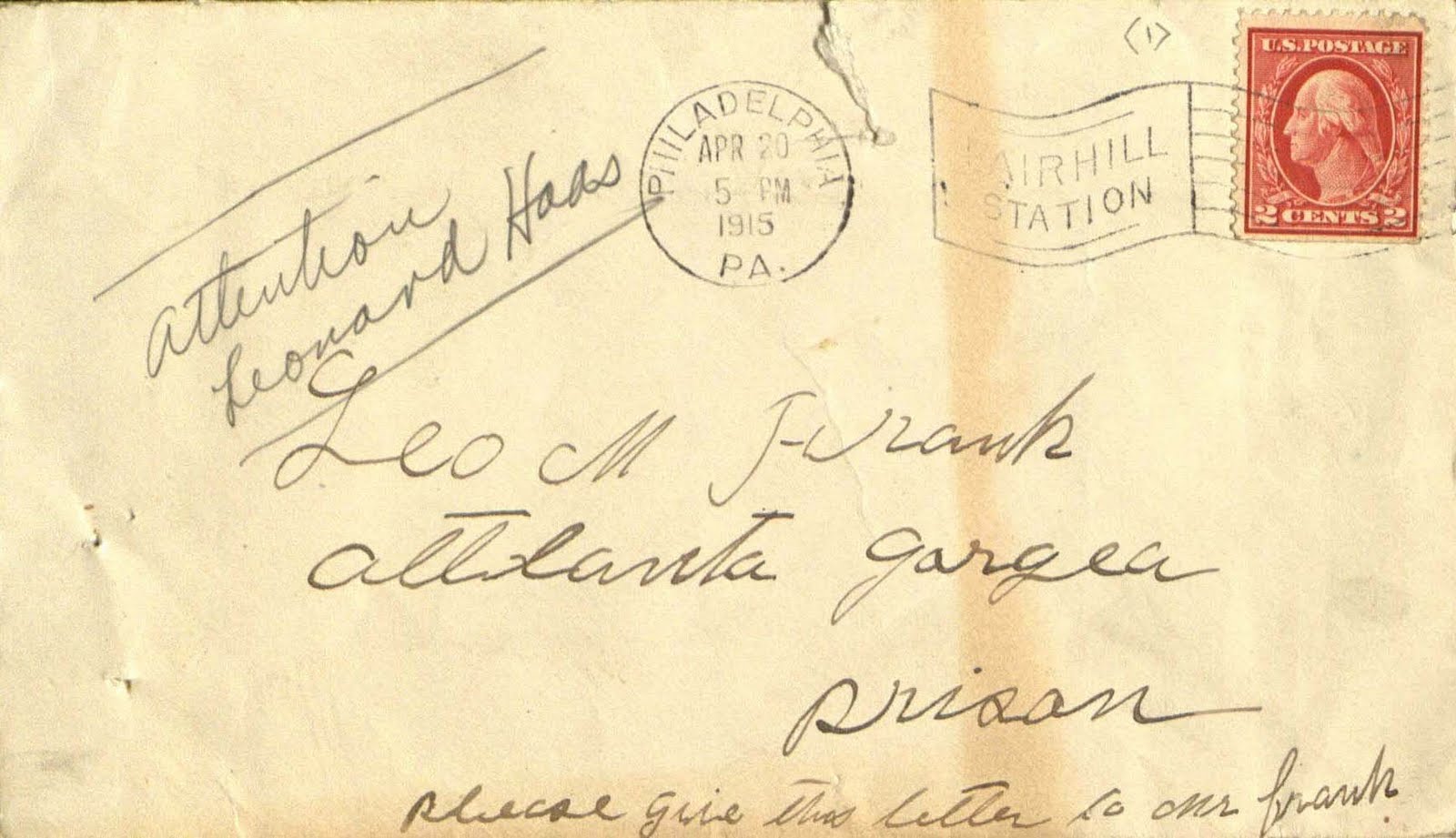

Some of the letters express support for Frank and affirm his innocence. One letter to Frank in prison, postmarked April 20, 1915, did not reach him before his death.  In it, a person signing himself “A Friend of Connelly’s” wrote: “Sir I know in my very heart and soul that it was Connelly that killed the Phagan girl…” It goes on: “the white folks never did treat me good so I need not cair [sic] whether you live or die but before me and my god Connelly [sic] killed Mary Phagan as true as death he did.” Jim Conley, the pencil factory’s custodian and an early suspect in the case, gave damning testimony that ultimately sealed Frank’s conviction. (Many years later, Conley’s lawyer proclaimed his belief in Frank’s innocence.)

In it, a person signing himself “A Friend of Connelly’s” wrote: “Sir I know in my very heart and soul that it was Connelly that killed the Phagan girl…” It goes on: “the white folks never did treat me good so I need not cair [sic] whether you live or die but before me and my god Connelly [sic] killed Mary Phagan as true as death he did.” Jim Conley, the pencil factory’s custodian and an early suspect in the case, gave damning testimony that ultimately sealed Frank’s conviction. (Many years later, Conley’s lawyer proclaimed his belief in Frank’s innocence.)

Other letters express outrage at Governor Slaton for commuting Frank’s sentence. On June 24, 1915, a letter to Slaton expressed the vow of “a body of reliable citizens” of Fulton County “to kill you regardless of time or your where-abouts, we expect to hang you by the neck with a rope until you are dead and riddle your body with bullets, no matter where you go, or where you stay, we intend to kill you and then kill Frank…” The letter is signed “Yours to destroy, The life takers.”

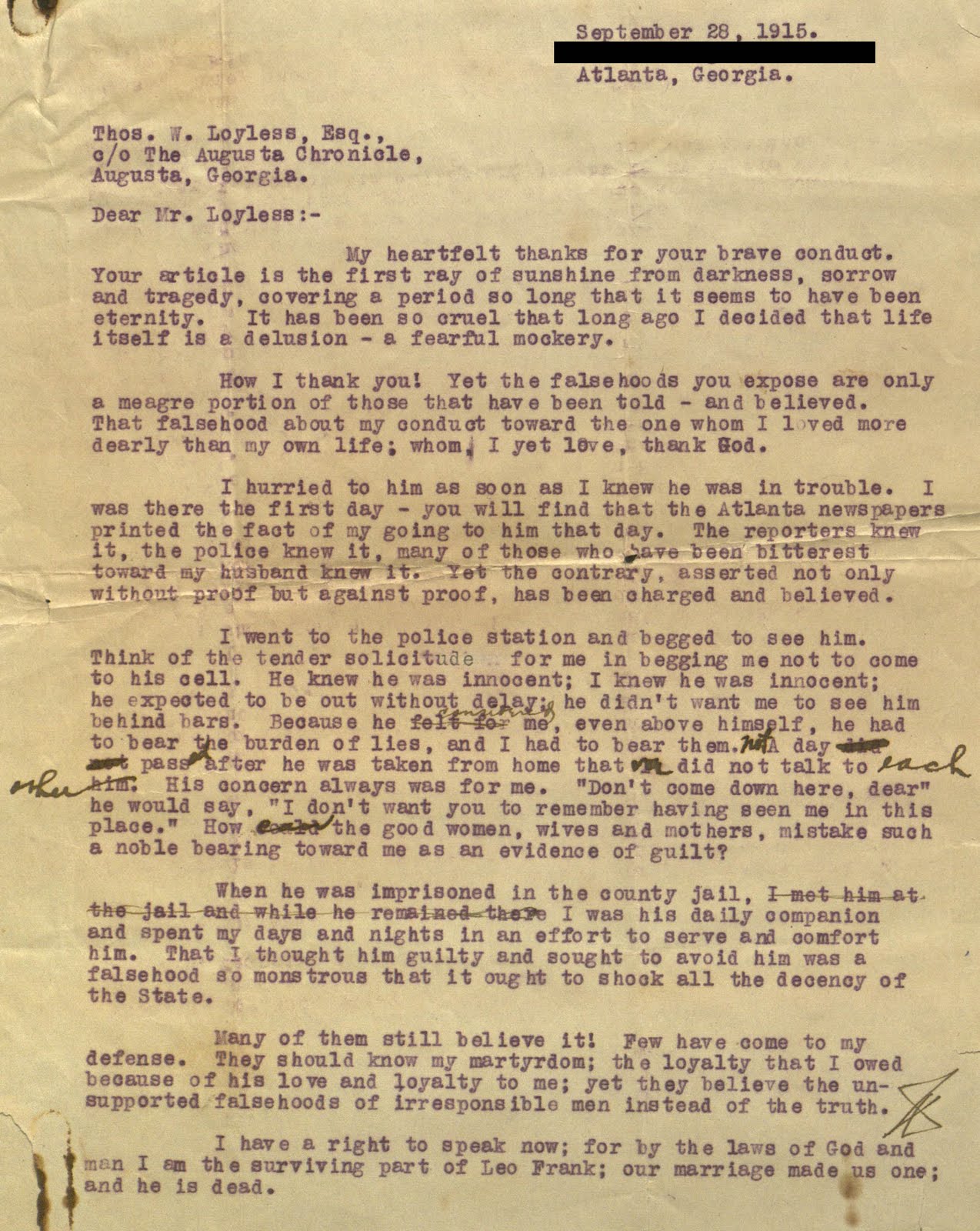

After Leo’s death, Lucille’s entry in her daily planner read: “My darling is buried; what has life for me now?” The following month, she wrote a letter to Thomas Loyless about her husband. “I only pray that those who destroyed his life will realize the truth before they meet their God—they perhaps are not entirely to blame, fed as they were on lies unspeakable, their passions aroused by designing persons….” she wrote. “But those who inspired these men to this awful act, what of them? Will not their conscience make for them a hell on earth, and will not their associates, in their hearts, despise them? … If there is a God—and I know there is—truth will prevail.” It was another seventy-one years before Leo Frank was pardoned by the State of Georgia, in 1986.

After Leo’s death, Lucille’s entry in her daily planner read: “My darling is buried; what has life for me now?” The following month, she wrote a letter to Thomas Loyless about her husband. “I only pray that those who destroyed his life will realize the truth before they meet their God—they perhaps are not entirely to blame, fed as they were on lies unspeakable, their passions aroused by designing persons….” she wrote. “But those who inspired these men to this awful act, what of them? Will not their conscience make for them a hell on earth, and will not their associates, in their hearts, despise them? … If there is a God—and I know there is—truth will prevail.” It was another seventy-one years before Leo Frank was pardoned by the State of Georgia, in 1986.

The Leo Frank Trial Collection is widely used by researchers from all over, including theater groups preparing for performances of the musical “Parade”, students researching the history of anti-Semitism in America, documentary filmmakers and many others. This collection was donated to the University in 1961 by Harold E. and Maxine Marcus. These materials were given to them by Mrs. Lucille Frank, widow of Leo Frank, and the aunt of Harold Marcus. Mrs. Frank was a life member of the Brandeis University National Women’s Committee (BUNWC) and died in 1957. The Marcuses were also active donors to the University (starting in the 1950s), and Mrs. Marcus was a founding member of the Atlanta Chapter of BUNWC and a permanent member of the National Board.