Eric M. Lipman Collection of Nazi Documents

March 31, 2011

Description and all translations from German by Clinton Walding, PhD candidate in history

The Eric M. Lipman collection of Nazi documents offers researchers and students alike a wide-ranging glimpse into the evolution of the Third Reich’s political and military apparatus, in addition to revealing salient aspects of Nazi racial policy in action. This unique set of documents exhibits how Nazi figures as well as institutions responded in the face of significant external and internal pressures, such as the assassination attempt upon Hitler on July 20, 1944, or the January 1945 bombing raids over München. The occasionally contentious interplay of prominent personalities and bureaucratic initiatives is also on full display.

The Eric M. Lipman collection of Nazi documents offers researchers and students alike a wide-ranging glimpse into the evolution of the Third Reich’s political and military apparatus, in addition to revealing salient aspects of Nazi racial policy in action. This unique set of documents exhibits how Nazi figures as well as institutions responded in the face of significant external and internal pressures, such as the assassination attempt upon Hitler on July 20, 1944, or the January 1945 bombing raids over München. The occasionally contentious interplay of prominent personalities and bureaucratic initiatives is also on full display.

A native of Stolzenau an der Weser, Germany, Eric M. Lipman graduated from the University of Geneva in Switzerland before emigrating to the United States in the late 1930s to escape the Holocaust. During World War II, he attained the post of Army Master Sergeant, specializing in enemy documents collection and analysis. Immediately following the war’s conclusion, Lipman remained to serve as a field investigator locating and preparing documents that would eventually be submitted to the International Military Tribunal in Nürnberg. He was honorably discharged in 1946 and worked abroad in industrial international trade before permanently relocating to Richmond, Virginia, in 1950. He graciously donated files from his personal collection as a gift to the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department in the early 1980s. Eric Lipman passed away on April 17, 1992.

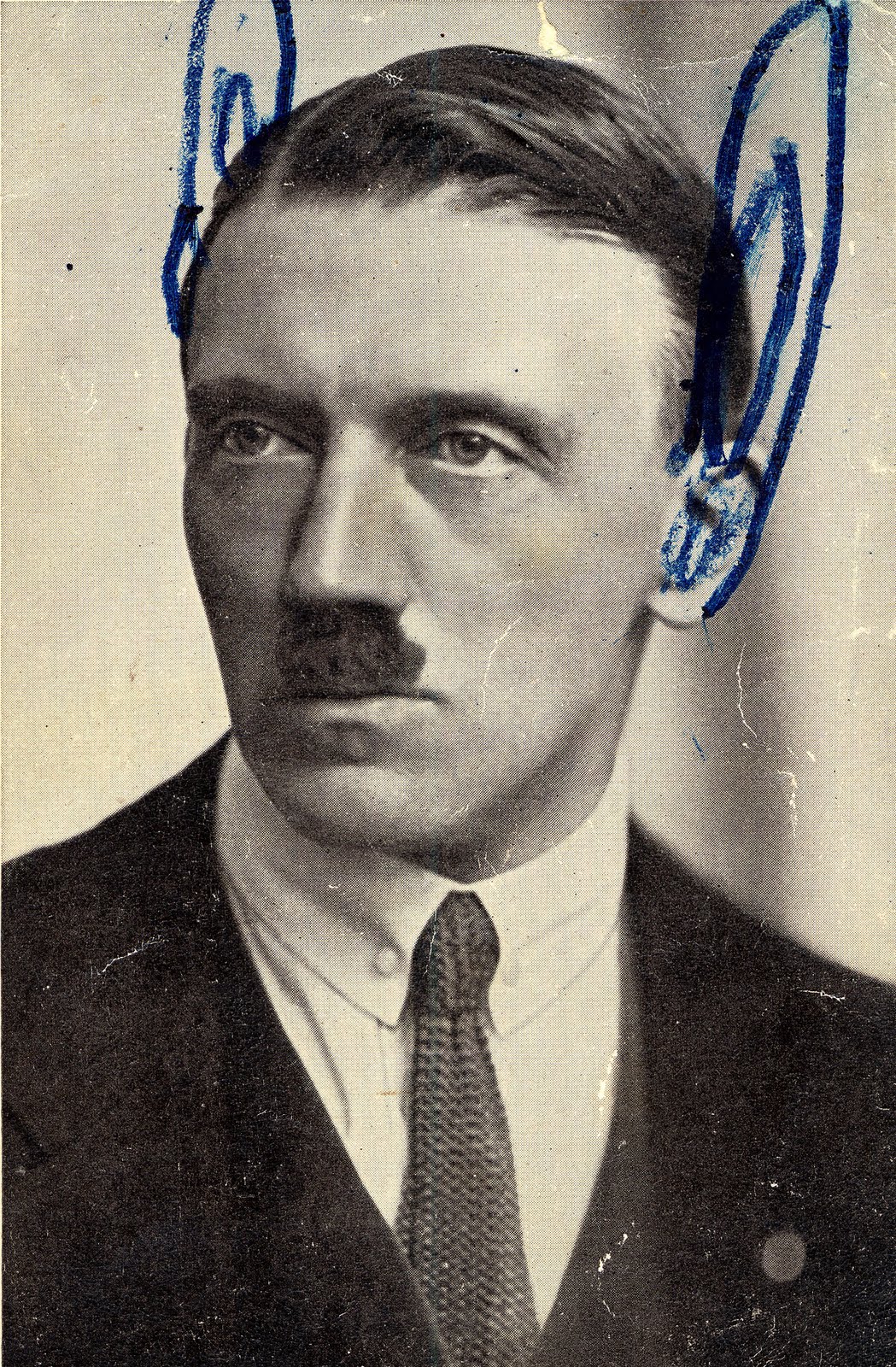

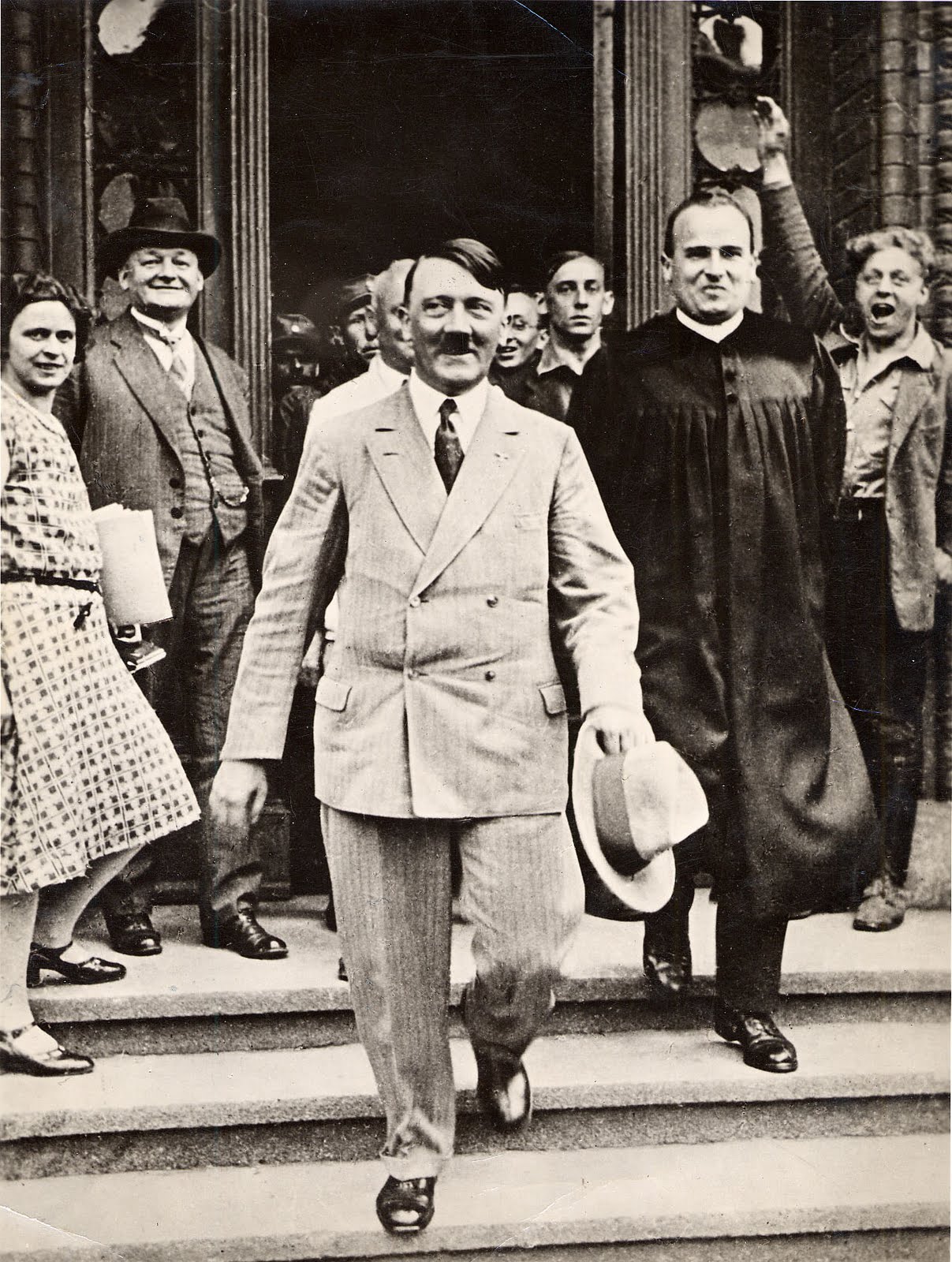

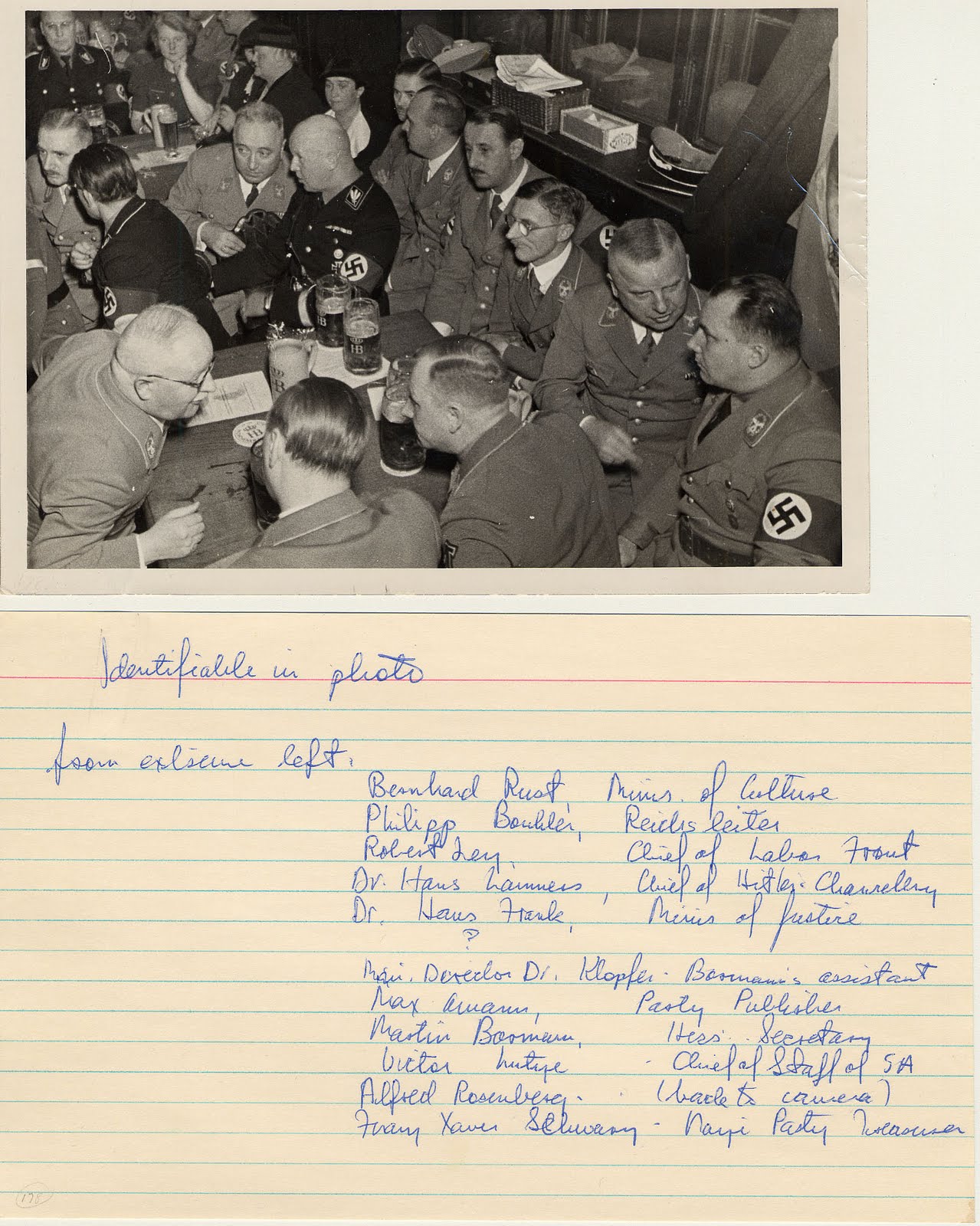

The collection at Brandeis, two linear feet in size, consists chiefly of correspondence written between 1921 and 1945, before and during World War II. As diverse as it is fragmented, the collection includes government letters and classified internal correspondence to and from Nazi party officials and military figures, war certificates, personal diaries and official decrees. Some of this correspondence indicates how early party and military leaders felt about aspects of Hitler’s reign as Führer during the initial phases of the National Socialist consolidation of power. Notable senders and recipients include Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels, Martin Bormann, Wilhelm Keitel, Ulrich Greifelt and Franz von Papen. A series of personal and official photographs and postcards rounds out the collection, many of which feature Hitler and other well-known Nazi officials.

The collection at Brandeis, two linear feet in size, consists chiefly of correspondence written between 1921 and 1945, before and during World War II. As diverse as it is fragmented, the collection includes government letters and classified internal correspondence to and from Nazi party officials and military figures, war certificates, personal diaries and official decrees. Some of this correspondence indicates how early party and military leaders felt about aspects of Hitler’s reign as Führer during the initial phases of the National Socialist consolidation of power. Notable senders and recipients include Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels, Martin Bormann, Wilhelm Keitel, Ulrich Greifelt and Franz von Papen. A series of personal and official photographs and postcards rounds out the collection, many of which feature Hitler and other well-known Nazi officials.

One of the more historically significant documents in the collection is a top-secret July 1942 letter from Heinrich Himmler to Wolfram Sievers. At the time, Himmler served as the Reichsführer of the SS (Schutzstaffel, or “Protection Squadron,” the Nazi party’s premier paramilitary organization), while Sievers was the Reichsgeschäftsführer (managing director) of the Ahnenerbe (Forschungs- und Lehrgemeinschaft das Ahnenerbe e.V., or “Research and Teaching Community for Ancestral Heritage”). This brief and seemingly innocuous letter serves as a clear indictment of the SS’s role in the establishment and financial sanctioning of medical experiments upon human subjects at Dachau concentration camp, as well as the Ahnenerbe’s integral role in physically conducting these atrocities. The Ahnenerbe billed itself as an intellectual society for the research and promotion of the Aryan “race,” and was deeply implicated in the intellectual justification of National Socialist ideology as well as ethnic resettlement initiatives and human medical experimentation.

The letter provides for the establishment of the Institut für Wehrwissenschaftliche Zweckforschung (“Institute for Military Scientific Research”) under the auspices of the Ahnenerbe and the personal direction of Sievers. This decree also allows the Ahnenerbe full use of facilities at Dachau concentration camp, and Sievers is pointedly instructed by Himmler to assist Dr. August Hirt “in every possible way” with his research. Examples of the scientific “research” conducted by this institute at Dachau include extensive human experimentation in order to determine safety thresholds for German servicemen in the Luftwaffe (Air Force); camp inmates were placed in vacuum chambers in order to simulate high-altitude conditions or exposed to freezing water for hours while naked to determine how long pilots could survive after being shot down over open water. Many subjects perished in the process. Himmler ends by noting that funding for these activities will come directly from the Waffen-SS. Sievers, a chief target of Allied prosecution at the infamous “Doctors’ Trial” at Nürnberg, was sentenced to death by hanging in August 1947.

The letter provides for the establishment of the Institut für Wehrwissenschaftliche Zweckforschung (“Institute for Military Scientific Research”) under the auspices of the Ahnenerbe and the personal direction of Sievers. This decree also allows the Ahnenerbe full use of facilities at Dachau concentration camp, and Sievers is pointedly instructed by Himmler to assist Dr. August Hirt “in every possible way” with his research. Examples of the scientific “research” conducted by this institute at Dachau include extensive human experimentation in order to determine safety thresholds for German servicemen in the Luftwaffe (Air Force); camp inmates were placed in vacuum chambers in order to simulate high-altitude conditions or exposed to freezing water for hours while naked to determine how long pilots could survive after being shot down over open water. Many subjects perished in the process. Himmler ends by noting that funding for these activities will come directly from the Waffen-SS. Sievers, a chief target of Allied prosecution at the infamous “Doctors’ Trial” at Nürnberg, was sentenced to death by hanging in August 1947.

The Lipman collection contains several official documents that collectively represent one of the most complete and compelling investigations to date into the local impact of the assassination attempt upon Hitler of July 20, 1944. Chief among these are a July and August 1944 internal report and attendant correspondence between Herbert Wiktorin, who was Wehrmacht (the collective armed forces of Germany) General of the Infantry, and Himmler and Hitler. Wiktorin served at the time as commander of Wehrkreis XIII in Gau Franconia, a Nazi administrative district headquartered in Nürnberg. Wiktorin provided a factual account as well as his own personal take on the struggle between the Führer headquarters and the Bendlerstraße (the building used as headquarters by high-ranking Wehrmacht officers who carried out the July 20 coup attempt) for the loyalty of local military commanders. Also documented in depth is the local civilian response to the coup attempt as demonstrated in allegedly spontaneous “loyalty rallies” to Hitler. Wiktorin also recorded a painstakingly detailed personal reconstruction of the events of July 20 and 21. Taken as a whole, the report reflects Wiktorin’s intense efforts to prove his unwavering personal loyalty to Hitler and the National Socialist regime.

The Lipman collection contains several official documents that collectively represent one of the most complete and compelling investigations to date into the local impact of the assassination attempt upon Hitler of July 20, 1944. Chief among these are a July and August 1944 internal report and attendant correspondence between Herbert Wiktorin, who was Wehrmacht (the collective armed forces of Germany) General of the Infantry, and Himmler and Hitler. Wiktorin served at the time as commander of Wehrkreis XIII in Gau Franconia, a Nazi administrative district headquartered in Nürnberg. Wiktorin provided a factual account as well as his own personal take on the struggle between the Führer headquarters and the Bendlerstraße (the building used as headquarters by high-ranking Wehrmacht officers who carried out the July 20 coup attempt) for the loyalty of local military commanders. Also documented in depth is the local civilian response to the coup attempt as demonstrated in allegedly spontaneous “loyalty rallies” to Hitler. Wiktorin also recorded a painstakingly detailed personal reconstruction of the events of July 20 and 21. Taken as a whole, the report reflects Wiktorin’s intense efforts to prove his unwavering personal loyalty to Hitler and the National Socialist regime.

An August 1944 letter addressed to Wiktorin indicates that he was summoned for interrogation by the chief of the SD (Sicherheitsdienst, the covert intelligence branch of the SS) in Nürnberg, and informs Wiktorin that the Gestapo and the SD suspect him of involvement in the July 20 plot. A terse birthday letter from Hitler to Wiktorin sent later that month appears to indicate that the Gestapo eventually cleared him of suspicion. A more “official” counterpoint intended for public consumption is found in a typed copy of a speech delivered on July 25, 1944, by Stellv. Gauleiter (Deputy Party Leader) Karl Holz, also of Wehrkries XIII, to the local Franconian population. This officially sanctioned version of the assassination attempt and its aftermath posits that “rarely has the faithful devotion to the Führer, has the Nazi attitude of loyalty so spontaneously and so movingly been expressed, as when the news of the criminal attack upon the life of the Führer became known.” Holz identifies the perpetrators as a “numerically vanishing small clique of treacherous officers” motivated by “reactionary desires” found in the “dark side of the caste spirit that National Socialism has always hated.” Holz repeatedly implores the local German population to keep their faith and loyalty to Hitler intact, and goes so far as to proclaim that “The healthy instinct of our people itself has spoken the death sentence for these machinations.”

An internal memo of August 28, 1944, circulated to all SD branches by Rudolf Brandt, Himmler’s personal administrator, echoes this general assessment, informing all recipients that the perpetrators of July 20 were a small “clique” of high-ranking Wehrmacht officers who did not in the least represent the overall loyal attitude of the Wehrmacht to the Führer. One of the crown jewels of the Eric M. Lipman collection is one of only four surviving original copies of a 70-page top-secret speech delivered by Hitler to high-ranking generals in Platterhof in June 1944. Wrought in oversized typescript, ostensibly so that Hitler did not have to don glasses in public, the speech took almost two full hours to deliver. The general tenor of the address is that the Third Reich is in no real danger of losing the war effort, and Hitler asserts that victory is inevitable “because we are the best organized state.” He goes on to note that Germany lost World War I because of “the traitors within—the Jews,” and that no such threat exists in 1944 since “I removed the Jews.” Interestingly, Hitler does betray certain doubts about the General Staff, noting, “If we win the war, then everyone will have done his duty….”

An internal memo of August 28, 1944, circulated to all SD branches by Rudolf Brandt, Himmler’s personal administrator, echoes this general assessment, informing all recipients that the perpetrators of July 20 were a small “clique” of high-ranking Wehrmacht officers who did not in the least represent the overall loyal attitude of the Wehrmacht to the Führer. One of the crown jewels of the Eric M. Lipman collection is one of only four surviving original copies of a 70-page top-secret speech delivered by Hitler to high-ranking generals in Platterhof in June 1944. Wrought in oversized typescript, ostensibly so that Hitler did not have to don glasses in public, the speech took almost two full hours to deliver. The general tenor of the address is that the Third Reich is in no real danger of losing the war effort, and Hitler asserts that victory is inevitable “because we are the best organized state.” He goes on to note that Germany lost World War I because of “the traitors within—the Jews,” and that no such threat exists in 1944 since “I removed the Jews.” Interestingly, Hitler does betray certain doubts about the General Staff, noting, “If we win the war, then everyone will have done his duty….”

The Lipman collection also contains a valuable cache of local documents originally from archival holdings of the SD in München. This file consists primarily of several local reports detailing the wide-ranging impact of British strategic bombing (referred to as a Terrorangriff, or “terror raid”) in January 1945 upon the civilian populace of München. These field reports record in painstaking statistical detail the tremendous loss of human life as well as the destruction of material resources and essential public services. Of particular importance, these internal reports identify the severely flagging public morale as a direct result of the “terror raids” and note that it is the most pressing threat to the Reich’s survival.

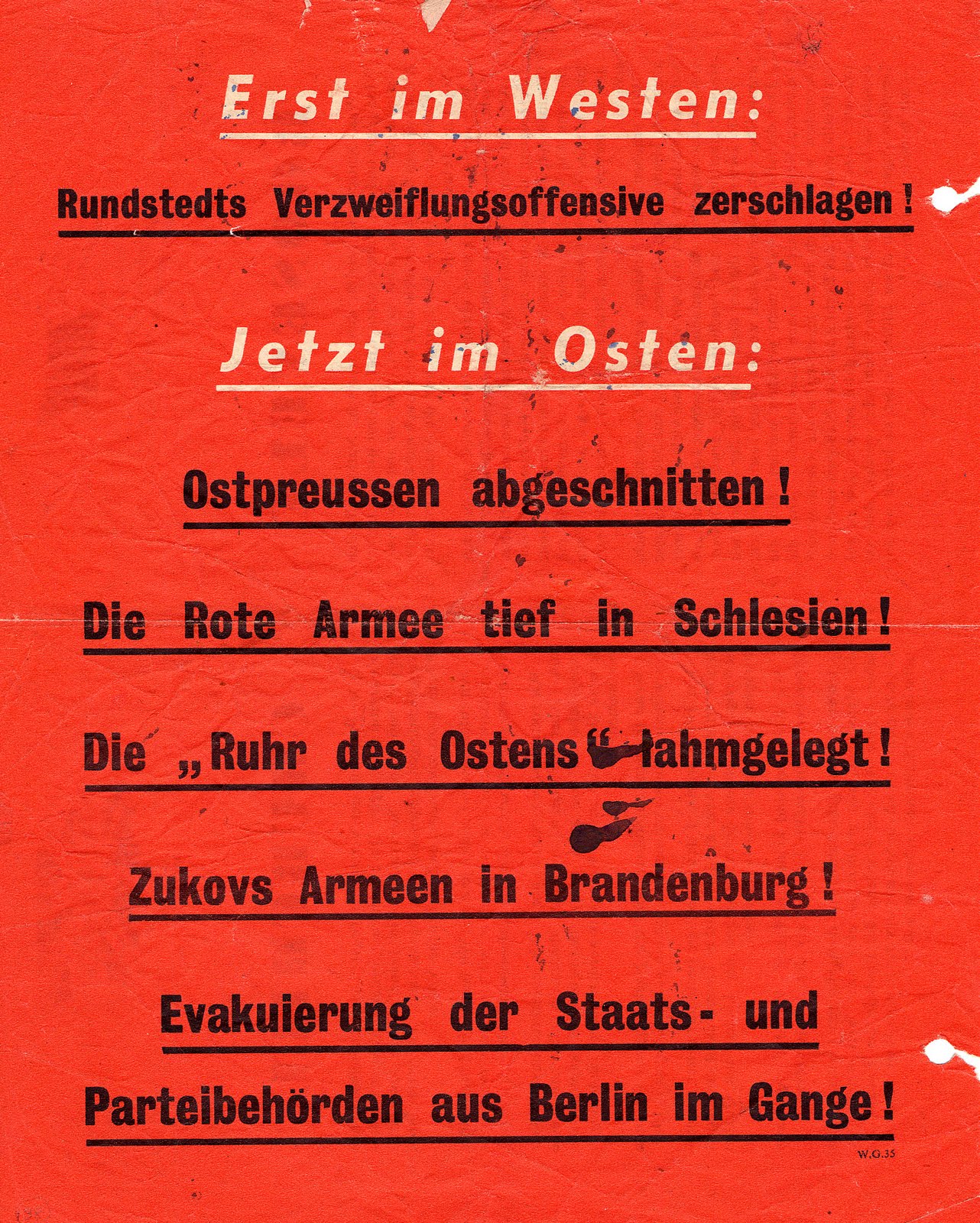

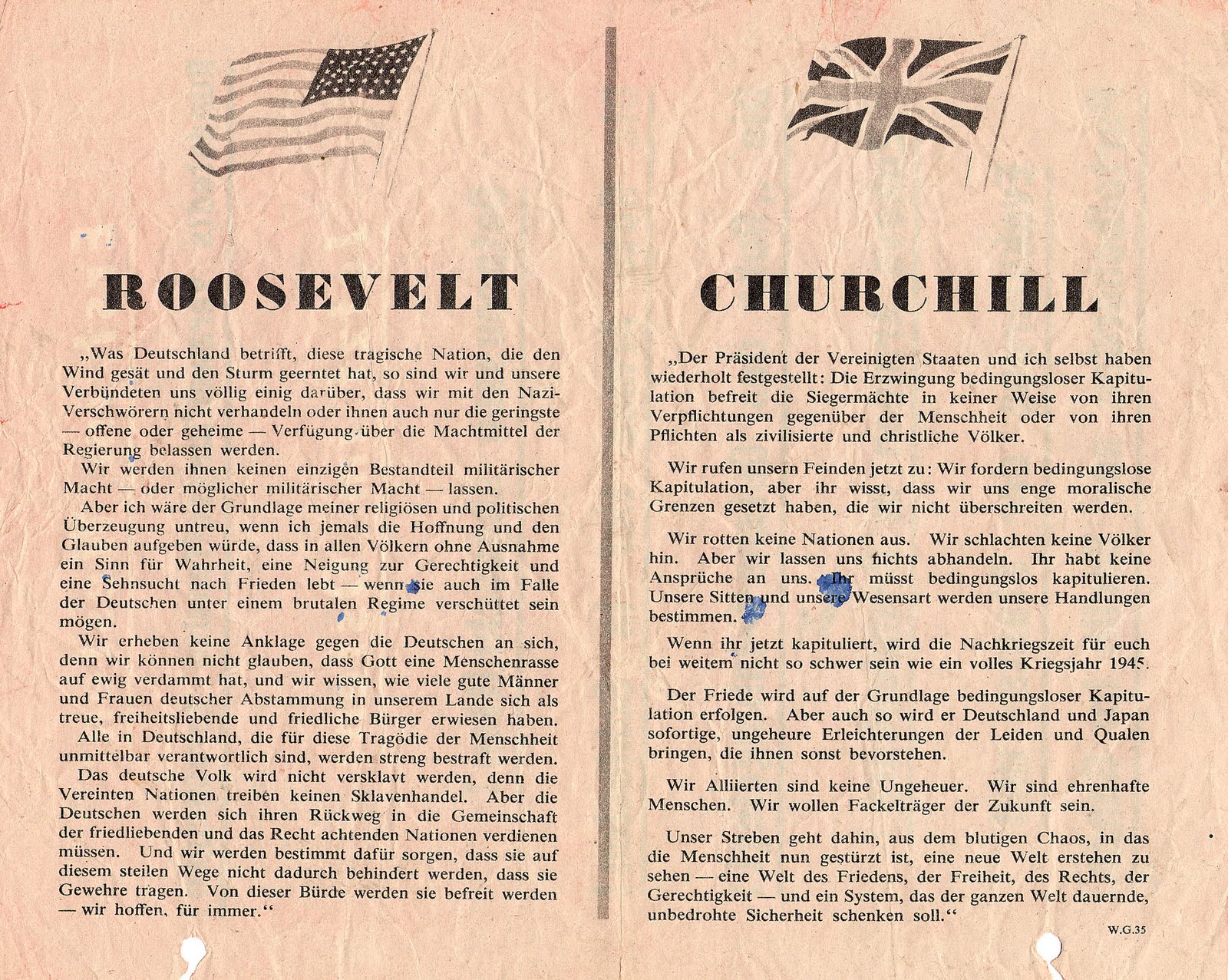

Interestingly, these archival documents are interspersed with Allied propaganda leaflets presumably dropped over München or the surrounding areas. An undated, striking red leaflet boldly proclaims: “East Prussia cut off! The Red Army deep in Silesia! The ‘Ruhr of the East’ paralyzed! Zukov’s army in Brandenburg! Evacuation of state and party officials in Berlin in progress!” The back of the leaflet features two sections entitled “Roosevelt” and “Churchill” along with their national flags, and extols the social and political virtues of each nation’s system while simultaneously denigrating the dictatorial nature of the Third Reich. Measuring the intended effectiveness of propagandistic efforts like this one remains a notoriously difficult scholarly task.

Interestingly, these archival documents are interspersed with Allied propaganda leaflets presumably dropped over München or the surrounding areas. An undated, striking red leaflet boldly proclaims: “East Prussia cut off! The Red Army deep in Silesia! The ‘Ruhr of the East’ paralyzed! Zukov’s army in Brandenburg! Evacuation of state and party officials in Berlin in progress!” The back of the leaflet features two sections entitled “Roosevelt” and “Churchill” along with their national flags, and extols the social and political virtues of each nation’s system while simultaneously denigrating the dictatorial nature of the Third Reich. Measuring the intended effectiveness of propagandistic efforts like this one remains a notoriously difficult scholarly task.

Also included are collected newspaper clippings from local München-area newspapers concerning the impact of strategic bombing upon civilian life. This file also contains secret reports by Gestapo informers and SD plainclothes officers who were tasked with covertly measuring the pulse of civilian morale. Collectively these documents indicate that the SS was extremely concerned with both quantifying as well as influencing the contours of popular opinion. The cumulative tenor of these reports indicates that the Allied strategic bombing of München in January 1945 proved devastating to civilian morale as well as inflicted staggering human casualties and widespread destruction of property.

Of particular interest are 1944 internal SS court documents that detail the peculiar and ultimately tragic local case involving ethnic ownership of the storied castle estate of Ostrometzko (in present-day Poland) of the von Alvensleben-Schönborn family. The vigorous von Alvensleben line had served Prussian kings for centuries, and Count Albrecht von Alvensleben inherited the sprawling 30,000-acre estate in 1873 through his marriage to Martha von Schönborn, a member of the Polish aristocracy. Their son Graf Joachim inherited the estate in 1915. Internal squabbles over money and the inheritance of the estate animated life for the Alvensleben-Schönborn family during most of the first half of the 20th century.

Hitler founded the Reichskommissar für die Festigung des deutschen Volkstums (“Reichs Commission for the Strengthening of Germandom”), or RKFDV, shortly after the invasion of Poland in October 1939; Heinrich Himmler officially held the commission. This agency was tasked with actively preparing Slavic-populated areas for resettlement by ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche). Central to this process was determining who belonged in the Deutsche Volksliste (“German People’s List”), a rigorous racial classification hierarchy developed by Himmler. Four broad grades determined what became of Poles of German descent (and, later, other “Slavic” populations such as those in Russia) in occupied territories: those in Category I were eligible for SS service and German citizenship, while those in Category IV were subject to forfeiture of their property, for instance. Those who refused to register risked being sent to concentration camps.

Hitler founded the Reichskommissar für die Festigung des deutschen Volkstums (“Reichs Commission for the Strengthening of Germandom”), or RKFDV, shortly after the invasion of Poland in October 1939; Heinrich Himmler officially held the commission. This agency was tasked with actively preparing Slavic-populated areas for resettlement by ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche). Central to this process was determining who belonged in the Deutsche Volksliste (“German People’s List”), a rigorous racial classification hierarchy developed by Himmler. Four broad grades determined what became of Poles of German descent (and, later, other “Slavic” populations such as those in Russia) in occupied territories: those in Category I were eligible for SS service and German citizenship, while those in Category IV were subject to forfeiture of their property, for instance. Those who refused to register risked being sent to concentration camps.

The court documents determine that for Count Graf Joachim von Alvensleben’s son Ludolf and his Italian wife, “The couple von Alvensleben have placed no application to the Volksliste (German People’s List) and have therefore been rejected for missing the application deadline.” The racial examiners involved in the case go on to note, “Apart from this Ludolf von Alvensleben is of Polish descent on his mother’s side. His wife suggests an impact of foreign blood.” The RKFDV eventually confiscated the property, and members of the family appear to have fallen on hard times. Ludolf von Alvensleben appears to have remained with his wife in Italy during the remainder of the war, with the report matter-of-factly concluding, “He has up until today found no need to return to the Reich.”

The court documents determine that for Count Graf Joachim von Alvensleben’s son Ludolf and his Italian wife, “The couple von Alvensleben have placed no application to the Volksliste (German People’s List) and have therefore been rejected for missing the application deadline.” The racial examiners involved in the case go on to note, “Apart from this Ludolf von Alvensleben is of Polish descent on his mother’s side. His wife suggests an impact of foreign blood.” The RKFDV eventually confiscated the property, and members of the family appear to have fallen on hard times. Ludolf von Alvensleben appears to have remained with his wife in Italy during the remainder of the war, with the report matter-of-factly concluding, “He has up until today found no need to return to the Reich.”

The unfortunate case of the von Alvensleben-Schönborn estate offers the researcher an instructive convergence point between the sprawling RKFDV bureaucracy and a local estate held by Volksdeutsche (“ethnic Germans”). What is rather apparent is the deadly earnestness and pseudoscientific precision with which the SS bureaucracy dealt with matters of racial citizenship, often with devastating material consequences. What also emerges is the incredible degree of racial scrutiny and classification ethnic Germans living abroad underwent during Nazi occupation of areas such as Poland. For many of these families of “questionable” Germanic descent, the Deutsche Volksliste and attendant litigation represented a precarious situation: the Nazi bureaucracy did not regard them as “pure” Germans, and as such they were subject to the vagaries of a system that included dispossession as well as death, while those of full Polish descent regarded them as despicable Nazi traitors and turncloaks.

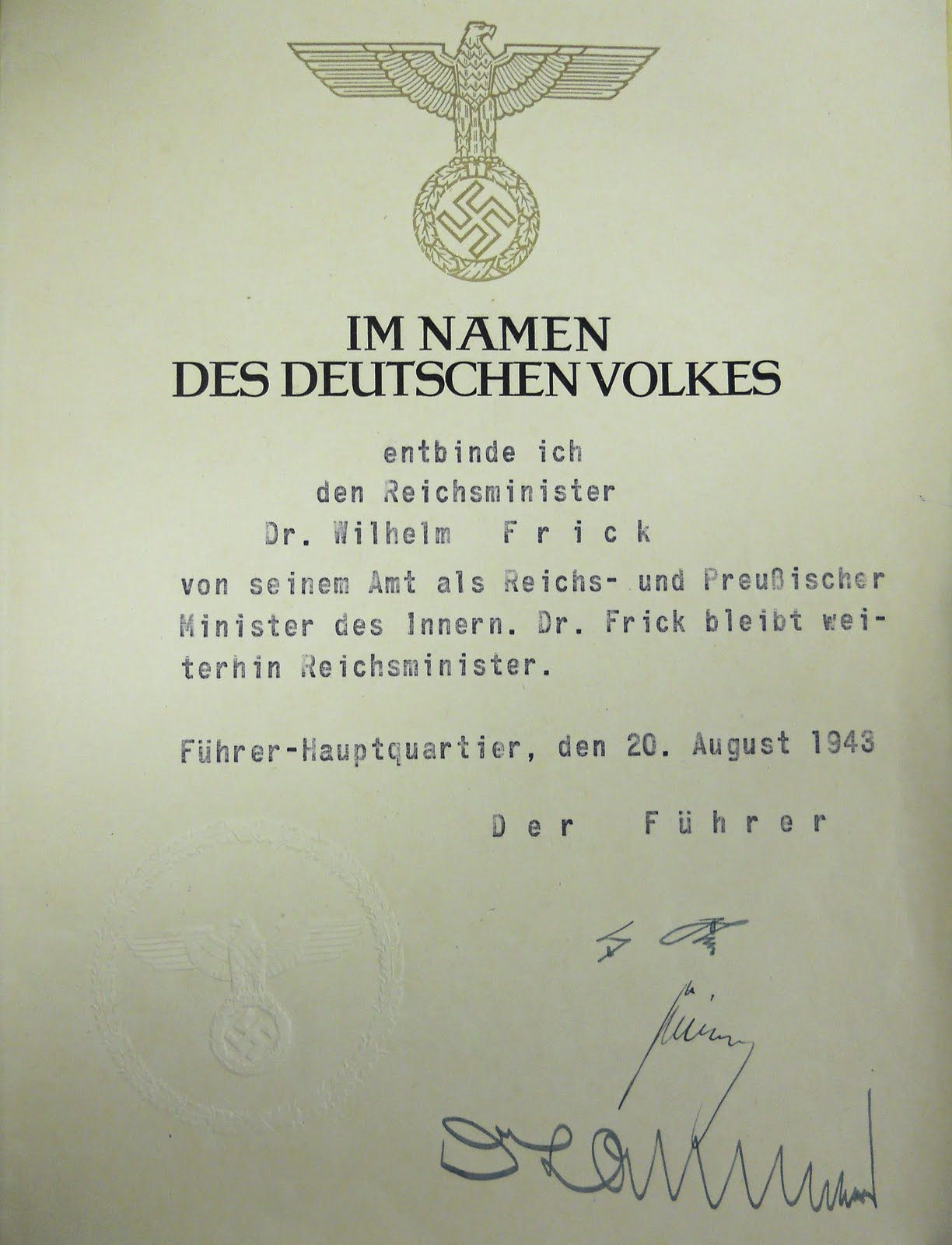

Other items of note include a handsome official 1943 decree dismissing Wilhelm Frick from his position as Minister des Innern (Minister of the Interior); this document is at once a historical document of significant import as well as a rare collector’s item. An extensive series of handwritten diaries kept by Wilhelm Frick and his second wife, Margarete Schultze-Naumburg, also deserves further academic scrutiny. The variegated holdings of the Eric M. Lipman collection represent a uniquely valuable resource to any serious researcher or student of the history of the Third Reich.