Nuremberg Chronicle (Liber Chronicarum)

November 27, 2010

Description by Craig Bruce Smith, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in history

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections possesses two rare editions of Dr. Hartmann Schedel’s “Nuremberg Chronicle”: the original Latin first edition of 1493 (given by the Bibliophiles of Brandeis University), and the vernacular edition published in German several months later (the gift of Lewis K. and Elizabeth Land). Composed in the 15th century in the city of Nuremberg—for which the book is named—the “Chronicle ”is “the first humanistic and scholastic world history in Germany.”[1] Encompassing religious, secular and mythical themes, this work is essentially a recompilation of ancient histories and medieval chronicles. The “Chronicle ” illustrates the strengths and limitations of early modern history, Renaissance learning and 15th-century understanding of the world.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections possesses two rare editions of Dr. Hartmann Schedel’s “Nuremberg Chronicle”: the original Latin first edition of 1493 (given by the Bibliophiles of Brandeis University), and the vernacular edition published in German several months later (the gift of Lewis K. and Elizabeth Land). Composed in the 15th century in the city of Nuremberg—for which the book is named—the “Chronicle ”is “the first humanistic and scholastic world history in Germany.”[1] Encompassing religious, secular and mythical themes, this work is essentially a recompilation of ancient histories and medieval chronicles. The “Chronicle ” illustrates the strengths and limitations of early modern history, Renaissance learning and 15th-century understanding of the world.

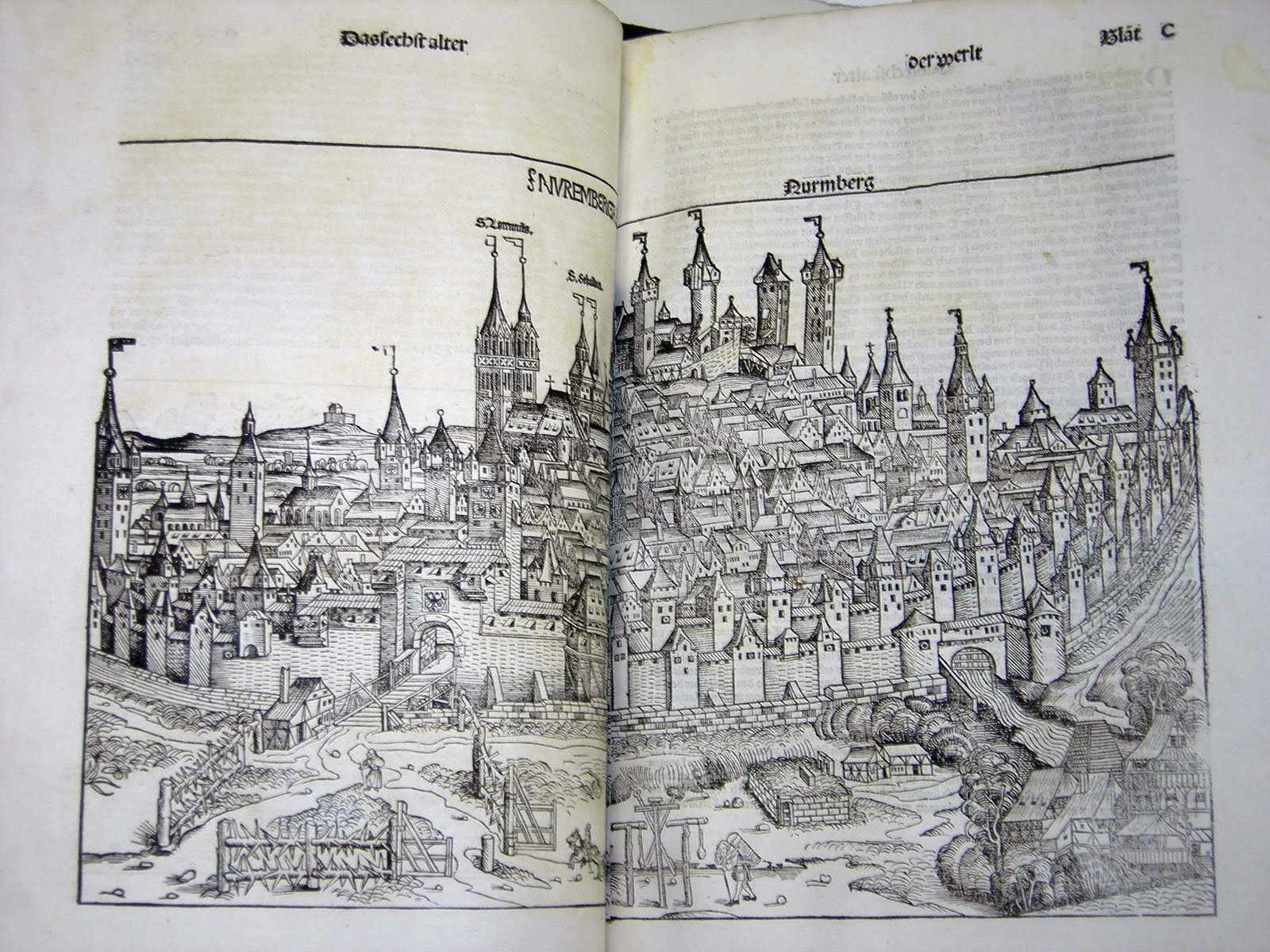

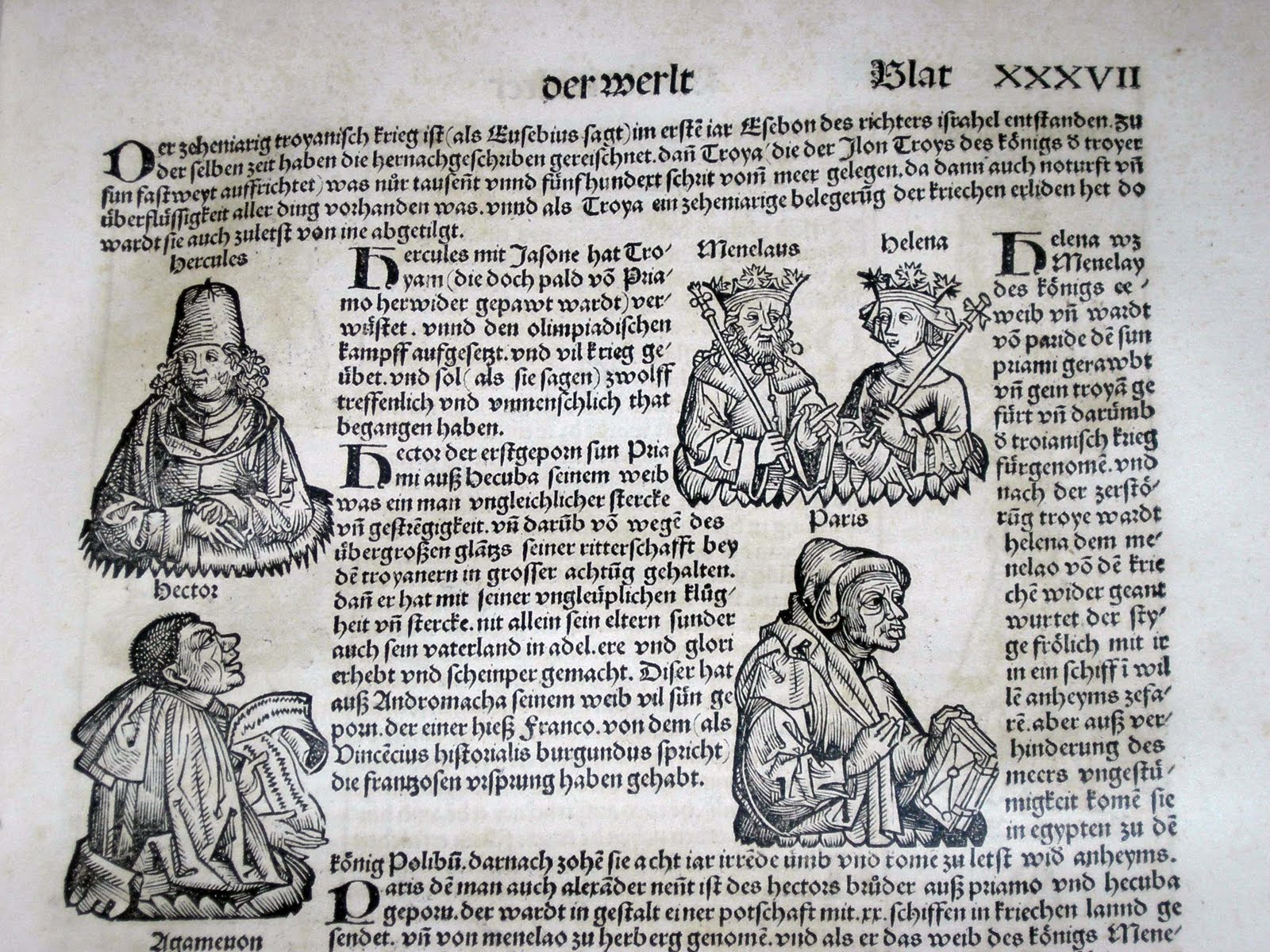

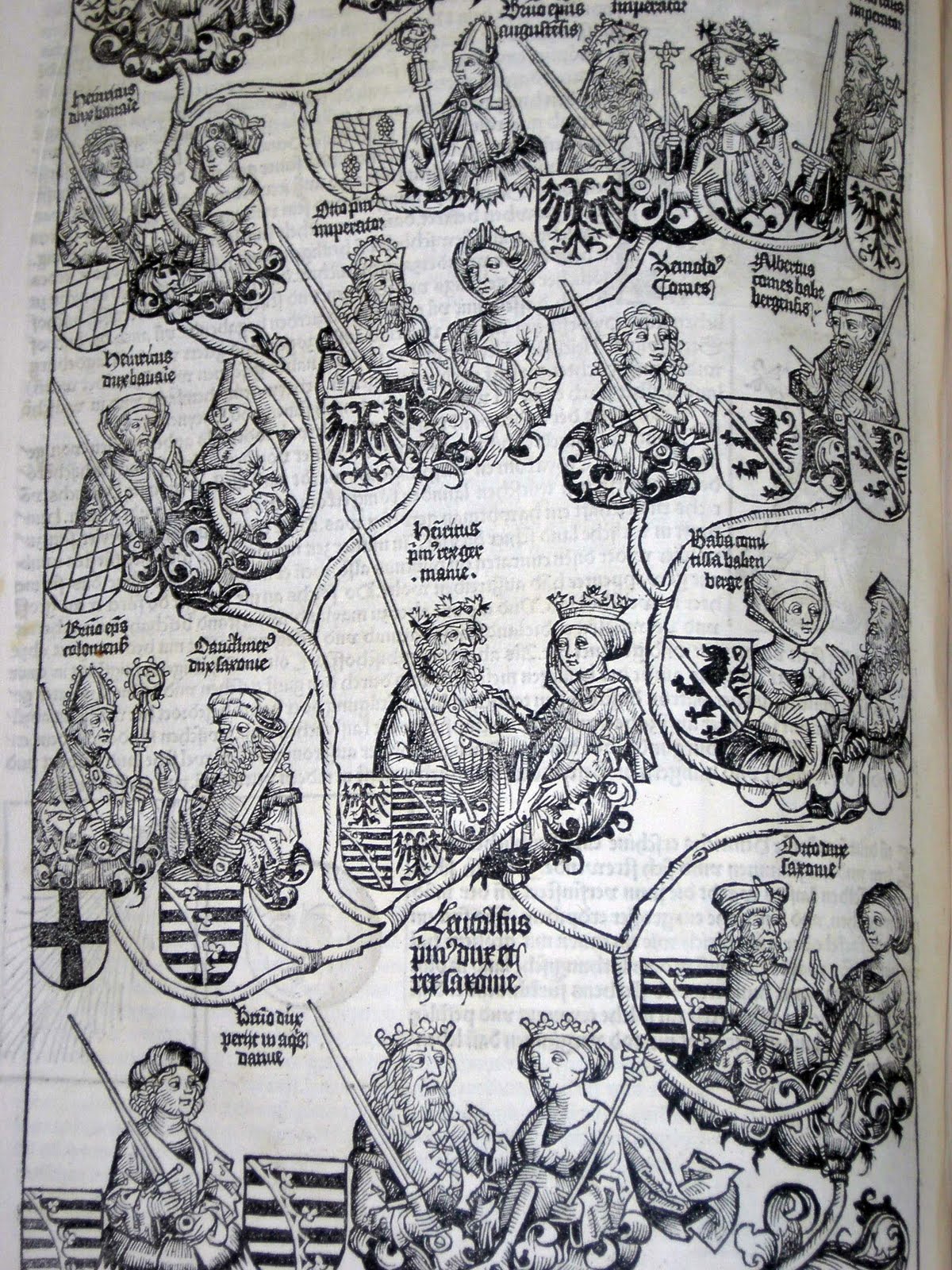

The most impressive aspect of the “Chronicle” is its exquisite printing and finely detailed woodcuts, which took over two years to complete. It was revolutionary for its incorporation of text with related images—virtually unheard-of prior to the 16th century. The creation of the book required an artist to draw an image before turning it over to be carved into a woodcut to be used for future printings. Designed and illustrated by Michael Wohlgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, the book contains over 1,800 images that are made from over 600 individual woodcuts—more than any other previously printed volume.[2] A teenaged Albrecht Dürer, who would go on to become a famed Renaissance painter, apprenticed under Wohlgemut during the initial phases of the illustration of the “Chronicle, ” leading to strong indications that some of the designs can be attributed directly to his hand, or at least to his influence.[3]

The most impressive aspect of the “Chronicle” is its exquisite printing and finely detailed woodcuts, which took over two years to complete. It was revolutionary for its incorporation of text with related images—virtually unheard-of prior to the 16th century. The creation of the book required an artist to draw an image before turning it over to be carved into a woodcut to be used for future printings. Designed and illustrated by Michael Wohlgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, the book contains over 1,800 images that are made from over 600 individual woodcuts—more than any other previously printed volume.[2] A teenaged Albrecht Dürer, who would go on to become a famed Renaissance painter, apprenticed under Wohlgemut during the initial phases of the illustration of the “Chronicle, ” leading to strong indications that some of the designs can be attributed directly to his hand, or at least to his influence.[3]

The “Nuremberg Chronicle” was first published by Anton Koberger, Europe’s largest printer, in Latin in June of 1493 for the elite and religious readership, with a subsequent German edition released in December for the literate upper-middle class. The German version, translated by the Nuremberg’s Treasury writer, George Alt, is slightly shorter and omits more esoteric detail than its Latin counterpart. Another small difference lies in the typeset employed by Koberger. The German edition features Schwabacher type, derived from a semi-Gothic form, while the Latin edition features the Italian Rotunda common to similar texts of the era.[4] While 800 Latin editions and only 408 German editions were printed, it was the later, smaller-run vernacular translation that enjoyed a higher proportionate degree of success after publication. Today, only 300 German editions exist throughout the world, and about 400 Latin editions.

The “Nuremberg Chronicle” was first published by Anton Koberger, Europe’s largest printer, in Latin in June of 1493 for the elite and religious readership, with a subsequent German edition released in December for the literate upper-middle class. The German version, translated by the Nuremberg’s Treasury writer, George Alt, is slightly shorter and omits more esoteric detail than its Latin counterpart. Another small difference lies in the typeset employed by Koberger. The German edition features Schwabacher type, derived from a semi-Gothic form, while the Latin edition features the Italian Rotunda common to similar texts of the era.[4] While 800 Latin editions and only 408 German editions were printed, it was the later, smaller-run vernacular translation that enjoyed a higher proportionate degree of success after publication. Today, only 300 German editions exist throughout the world, and about 400 Latin editions.

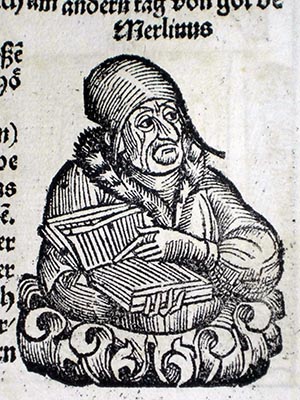

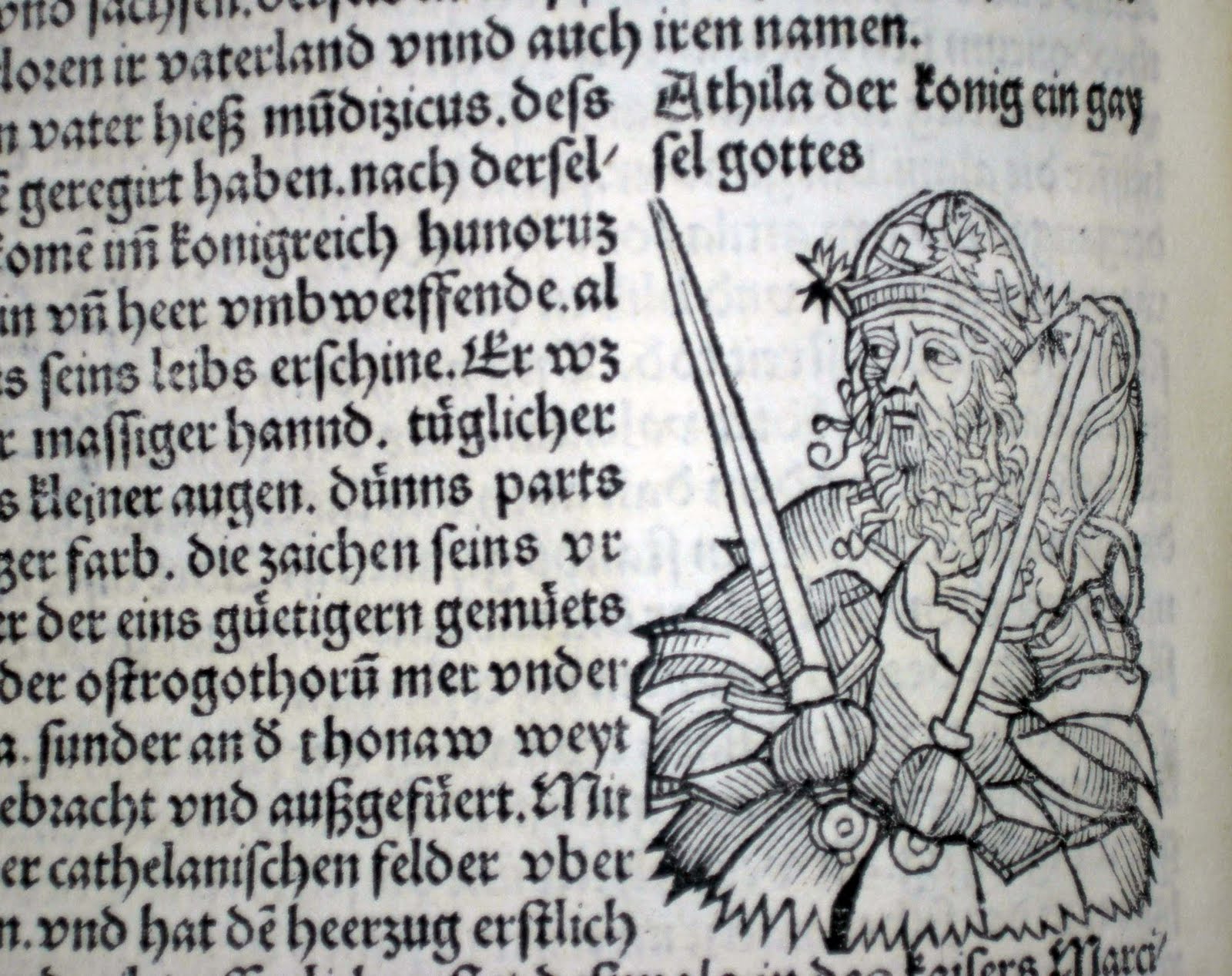

Among other images, the massive collection of woodcuts prominently features European cityscapes, Biblical scenes and royal and papal portraits, as well as depictions of legendary scenes and figures. For instance, a portrait of Merlin, the sorcerer of Arthurian fame, can be found displayed among those of true historical figures, such as Attila the Hun or the crown heads of Europe.

Perhaps the most controversial and incendiary aspect of the book, defaced in numerous copies but intact in both Brandeis copies, is the image of Pope Joan. The “Nuremberg Chronicle” perpetuated a legend that was supported by men such as Martin Luther and even promulgated by some authors and filmmakers well into the 21st century.[5] The tale claimed that a woman disguised as a man was elected as a pope of the Catholic Church in the ninth century, only to be exposed when she gave birth to a child during a service. The image of Joan, depicted with her newborn child, can be found discreetly among the portraits of actual Catholic popes. The “Chronicle ” “breaks with conventional narratives, in which the beginning of Joan’s motherhood marks the end of her pontificate, to portray her as simultaneously pope and mother.”[6] Once again, it is through imagery that Schedel’s work most clearly presents the blending of fact and lore as history.

Perhaps the most controversial and incendiary aspect of the book, defaced in numerous copies but intact in both Brandeis copies, is the image of Pope Joan. The “Nuremberg Chronicle” perpetuated a legend that was supported by men such as Martin Luther and even promulgated by some authors and filmmakers well into the 21st century.[5] The tale claimed that a woman disguised as a man was elected as a pope of the Catholic Church in the ninth century, only to be exposed when she gave birth to a child during a service. The image of Joan, depicted with her newborn child, can be found discreetly among the portraits of actual Catholic popes. The “Chronicle ” “breaks with conventional narratives, in which the beginning of Joan’s motherhood marks the end of her pontificate, to portray her as simultaneously pope and mother.”[6] Once again, it is through imagery that Schedel’s work most clearly presents the blending of fact and lore as history.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections’ editions of the “Nuremberg Chronicle” provide researchers with access to a scarce historical text still vibrant in its original bold black ink, virtually unaltered since leaving a Nuremberg printer over six centuries ago. The “Chronicle” can provide an understanding not only of Renaissance knowledge, but also of art, culture and the development of printing.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections’ editions of the “Nuremberg Chronicle” provide researchers with access to a scarce historical text still vibrant in its original bold black ink, virtually unaltered since leaving a Nuremberg printer over six centuries ago. The “Chronicle” can provide an understanding not only of Renaissance knowledge, but also of art, culture and the development of printing.

Notes

Wilson, Adrian. “The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle.” Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1976, p. 21.

Wilson, Adrian. “The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle.” Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1976, p. 21.- Ibid., p. 42.

- Ibid., p. 60.

- Ibid., p. 184.

- Stanford, Peter. “The Legend of Pope Joan: In Search of the Truth.” New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, p. 104.

- Rustici, Craig M. “The Afterlife of Pope Joan: Deploying the Popess Legend in Early Modern England.” Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006, p. 27.

Secondary Sources

Boureau, Alain. “The Myth of Pope Joan.” Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Boureau, Alain. “The Myth of Pope Joan.” Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

“Nuremberg Chronicle,” Morse Library, Beloit College.

“Nuremberg Chronicle,” Special Collections, University of Maryland.

Rustici, Craig M. “The Afterlife of Pope Joan: Deploying the Popess Legend in Early Modern England.” Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

Stanford, Peter. “The Legend of Pope Joan: In Search of the Truth.” New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998.

Wilson, Adrian. “The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle.” Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1976.

Wood, Clement. “The Woman Who Was Pope: A Biography of Pope Joan,” 853-855 AD. New York: William Faro, Inc., 1931.