Thomas Paine's Common Sense, 1776

August 2, 2015

Description by Kenneth Hong, Brandeis undergraduate and special contributor to the Special Collections Spotlight.

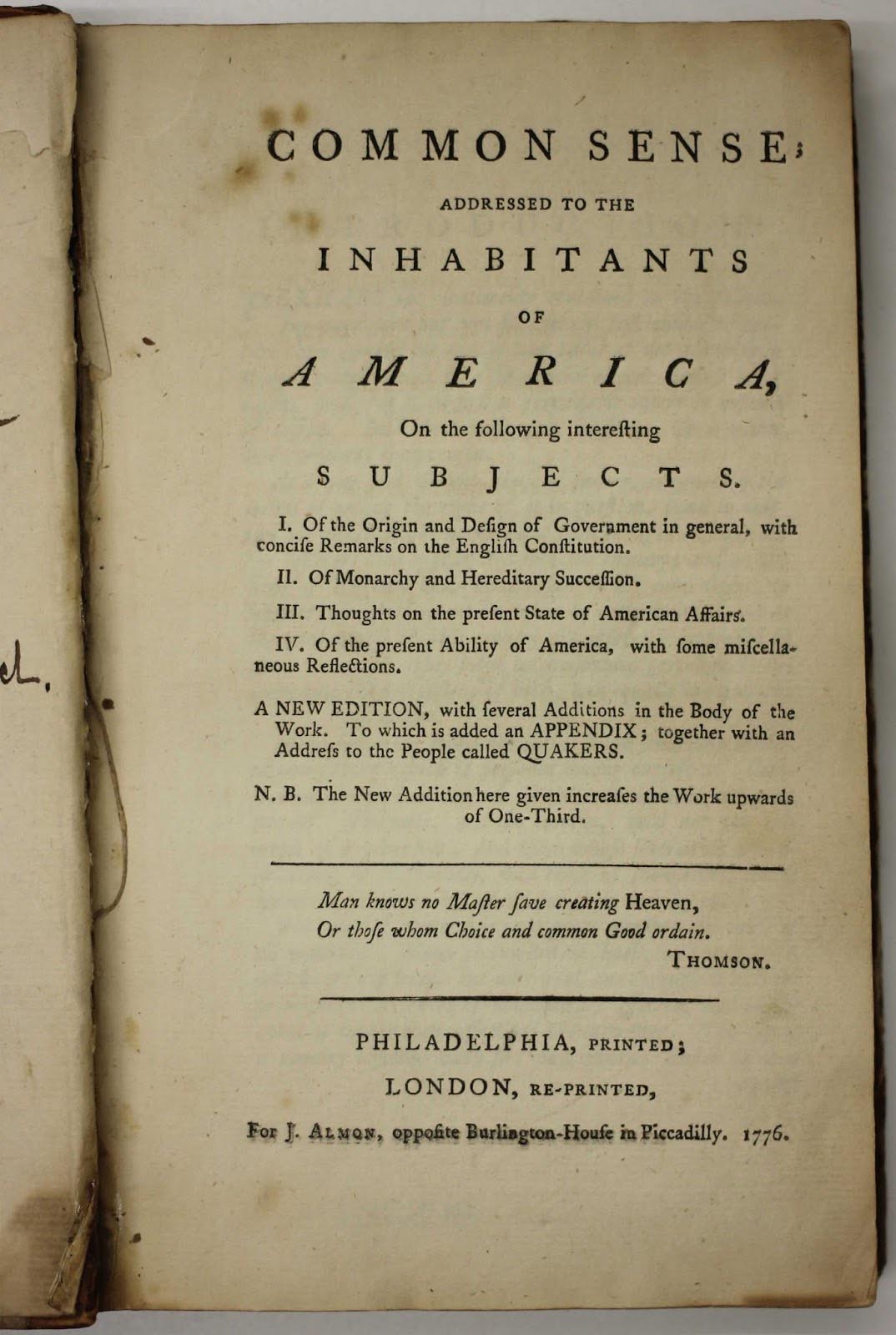

Amid the campus grounds of Brandeis University, housed in the Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections, is one of America’s most significant primary documents, a pamphlet, written by Thomas Paine: “Common Sense.” This pamphlet, donated by Nettie Podell Ottenberg, is an original copy of the 1776 London edition. Thomas Paine awakened the world with his quill and ink; with delicate yet intense force, with the masterful use of language, he gave birth to “Common Sense,” from which ignited a revolution.

Amid the campus grounds of Brandeis University, housed in the Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections, is one of America’s most significant primary documents, a pamphlet, written by Thomas Paine: “Common Sense.” This pamphlet, donated by Nettie Podell Ottenberg, is an original copy of the 1776 London edition. Thomas Paine awakened the world with his quill and ink; with delicate yet intense force, with the masterful use of language, he gave birth to “Common Sense,” from which ignited a revolution.

“Common Sense,” published on January 10, 1776, was originally printed in the city of Philadelphia, but was soon reprinted across America and Great Britain, and translated into German and Danish.[1] Thomas Paine’s pamphlet was first published anonymously, due to fears that its contents would be construed as treason; it was simply signed, “by an Englishman”.[2] The version housed at Brandeis University is one of the London printings, which had hiatuses, where words and phrases were omitted that were offensive to the British crown.[3] “Common Sense” sold about 120,000 copies in the first three months alone, being read in taverns and meeting houses across the 13 original colonies (the U.S. Census Bureau estimates the population in 1776 to be about 2.5 million and today to be about 320 million, that would make it proportionally equivalent to selling 15,000,000 copies today!)[4]

The 48-page pamphlet was the fuel that the colonists needed to have courage to rise against the British Empire, an astonishing contemplation for a common, non-militarized people to consider. Writing during a time when Kings and Monarchs ruled, Paine advocated for a government by the people, a highly innovative idea at the time. The colonists, still very much connected to the King and English ways, had not publicly voiced ideas of independence, and perhaps had not even brought the idea into consciousness; nevertheless, thoughts of independence were not far below the surface. Newspaper articles printed in response to Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” portray a nation that seemed to have outgrown its parent, ready to step out on its own. The Essex Gazette printed a letter on March 17, 1776, which read, in part: “In your famous pamphlet entitled ‘Common Sense,’ by which I am convinced of the necessity of Independence, to which I was before averse, you have given liberty to every individual to contribute materials for that great building, the grand charter of American Liberty.”[5] And from The New-London [Connecticut] Gazette, on 22 March 1776, “The doctrine of Independence hath been in times past greatly disgustful; we abhorred the principle. It is now become our delightful theme and commands our purest affections. We revere the author and highly prize and admire his works.”[6] Interestingly, the publishing date of “Common Sense” in January 1776 was only six months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and was perhaps a driving force behind the signing of that infamous document. “Common Sense” not only united average citizens and their political leaders behind the idea of independence, it transformed a colonial quarrel into the American Revolution.

The 48-page pamphlet was the fuel that the colonists needed to have courage to rise against the British Empire, an astonishing contemplation for a common, non-militarized people to consider. Writing during a time when Kings and Monarchs ruled, Paine advocated for a government by the people, a highly innovative idea at the time. The colonists, still very much connected to the King and English ways, had not publicly voiced ideas of independence, and perhaps had not even brought the idea into consciousness; nevertheless, thoughts of independence were not far below the surface. Newspaper articles printed in response to Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” portray a nation that seemed to have outgrown its parent, ready to step out on its own. The Essex Gazette printed a letter on March 17, 1776, which read, in part: “In your famous pamphlet entitled ‘Common Sense,’ by which I am convinced of the necessity of Independence, to which I was before averse, you have given liberty to every individual to contribute materials for that great building, the grand charter of American Liberty.”[5] And from The New-London [Connecticut] Gazette, on 22 March 1776, “The doctrine of Independence hath been in times past greatly disgustful; we abhorred the principle. It is now become our delightful theme and commands our purest affections. We revere the author and highly prize and admire his works.”[6] Interestingly, the publishing date of “Common Sense” in January 1776 was only six months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and was perhaps a driving force behind the signing of that infamous document. “Common Sense” not only united average citizens and their political leaders behind the idea of independence, it transformed a colonial quarrel into the American Revolution.

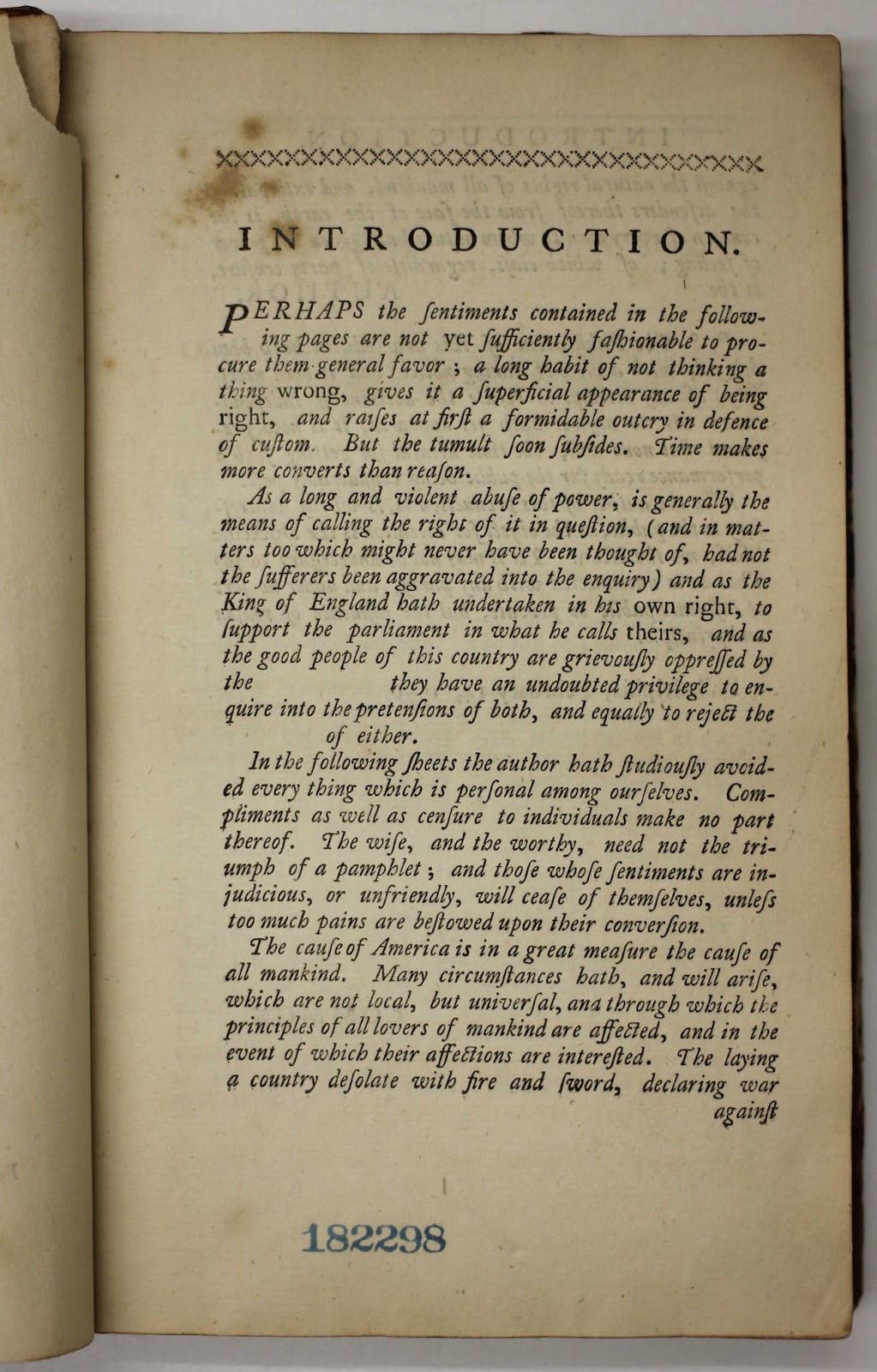

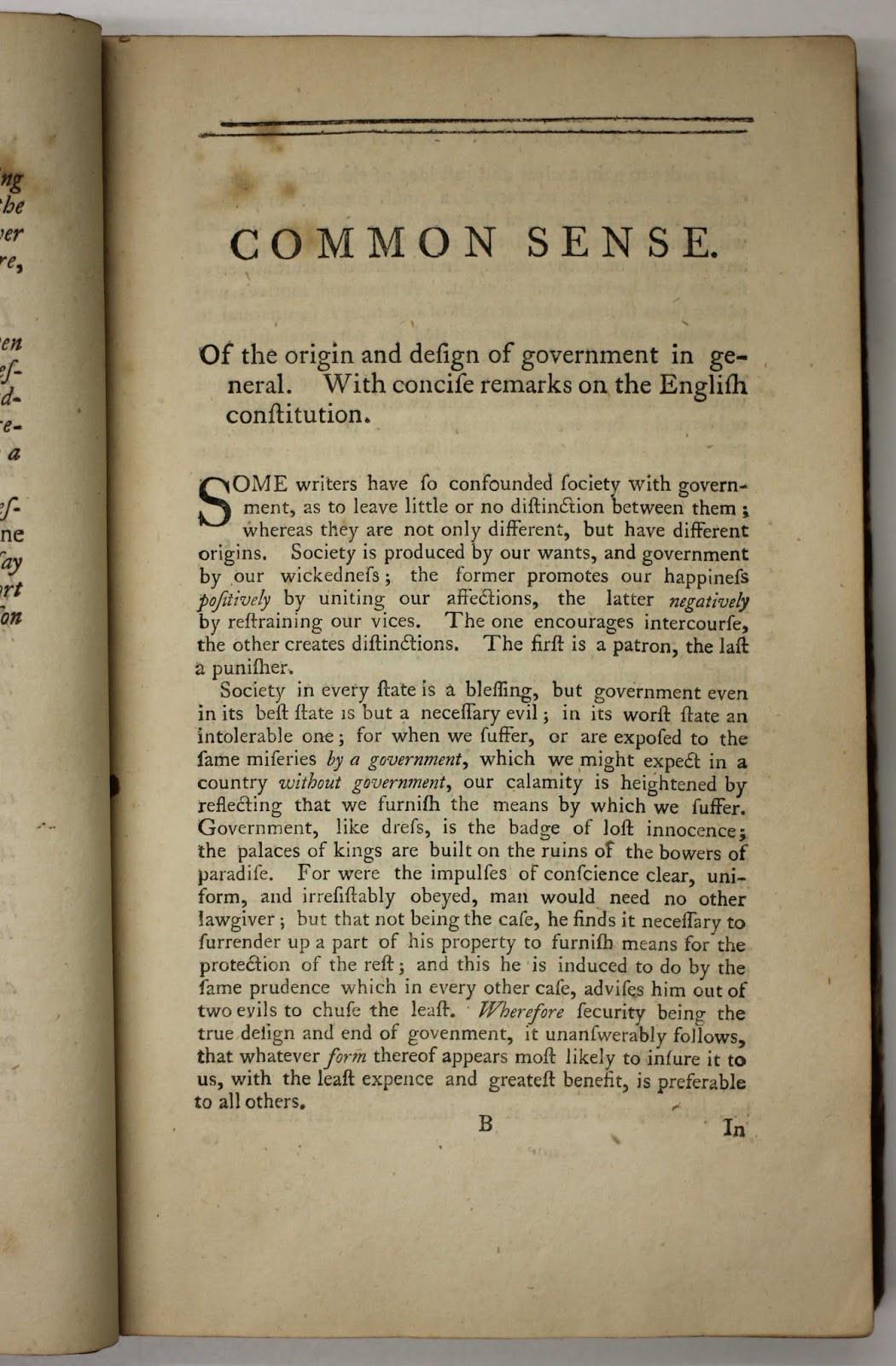

“Common Sense” makes for straightforward reading. Paine’s words are strong and honest; he writes with courage, makes no apologies, asks for no forgiveness. The pamphlet is split into four main sections, preceded by an introduction. Paine begins his writing with a challenge, at once giving the people permission to consider what is truly right and what is wrong: “Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not YET sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favour; a long habit of not thinking a thing WRONG, gives it a superficial appearance of being RIGHT, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom.”[7] Later, Paine discusses the absurdity of an island (England) governing an entire continent (America): “Small islands, not capable of protecting themselves, are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care; but there is something absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.”[8] Researchers will find Paine’s pamphlet useful as insight into the relationship between the crown and the colonists as it existed at that time, and as a window into the soul of the colonists given how quickly and to the extent that Paine’s ideas were adopted and affected the direction of America.

“Common Sense” makes for straightforward reading. Paine’s words are strong and honest; he writes with courage, makes no apologies, asks for no forgiveness. The pamphlet is split into four main sections, preceded by an introduction. Paine begins his writing with a challenge, at once giving the people permission to consider what is truly right and what is wrong: “Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not YET sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favour; a long habit of not thinking a thing WRONG, gives it a superficial appearance of being RIGHT, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom.”[7] Later, Paine discusses the absurdity of an island (England) governing an entire continent (America): “Small islands, not capable of protecting themselves, are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care; but there is something absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.”[8] Researchers will find Paine’s pamphlet useful as insight into the relationship between the crown and the colonists as it existed at that time, and as a window into the soul of the colonists given how quickly and to the extent that Paine’s ideas were adopted and affected the direction of America.

Paine used his writing as his weapon against the crown. With masterful language, Paine united the will of the colonists, planting the seed and giving hope and inspiration to fulfill the dream of America as an independent nation. The pamphlet was originally published without his name and all of the royalties associated with “Common Sense” were donated to the Continental Army.[9] It would appear that Paine was looking for neither fame nor fortune in writing a pamphlet that profoundly affected the creation of a nation. To Paine, these ideas came naturally, they were simply, “Common Sense.”

Notes

- Powell, Jim. “Thomas Paine, Passionate Pamphleteer for Liberty,” in The Freeman, January 1, 1996. Foundation for Economic Education. Accessed March 11, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Entry for Call# D793.P147c. Brown University Library Online Catalog. Accessed March 12, 2015.

- Harvey Kaye. “Common Sense and the American Revolution.” The Thomas Paine National Historical Association. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- “Praise for Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, 1776 as Reported in American Newspapers,” in “America in Class: Making the Revolution: America, 1763-1791: Primary Source Collection.” The National Humanities Center. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Paine, Thomas. Common Sense. London: J. Almon, 1776.

- Ibid.

- Kaye, Accessed February 10, 2015.

This essay, by Brandeis undergraduate Kenneth Hong, resulted from a Spring 2015 course for the Myra Kraft Transitional Year Program, taught by Dr. Craig Bruce Smith, entitled, “Preserving Boston’s Past: Public History and Digital Humanities.” In this course, students worked with archival materials, developed website content, and produced their own commemoration event, “The 250th Anniversary of the Stamp Act: A Revolutionary Exhibit and Performance,” marking one of the first steps of the American Revolution.

The Transitional Year Program was established in 1968 and was renamed in 2013 for Myra Kraft ‘64, the late Brandeis alumna and trustee. It provides small classes and strong support systems for students who have had limitations to their precollege academic opportunities.