Paul Iribe's Le Témoin

December 16, 2009

Description by Surella Evanor Seelig, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in the comparative history program

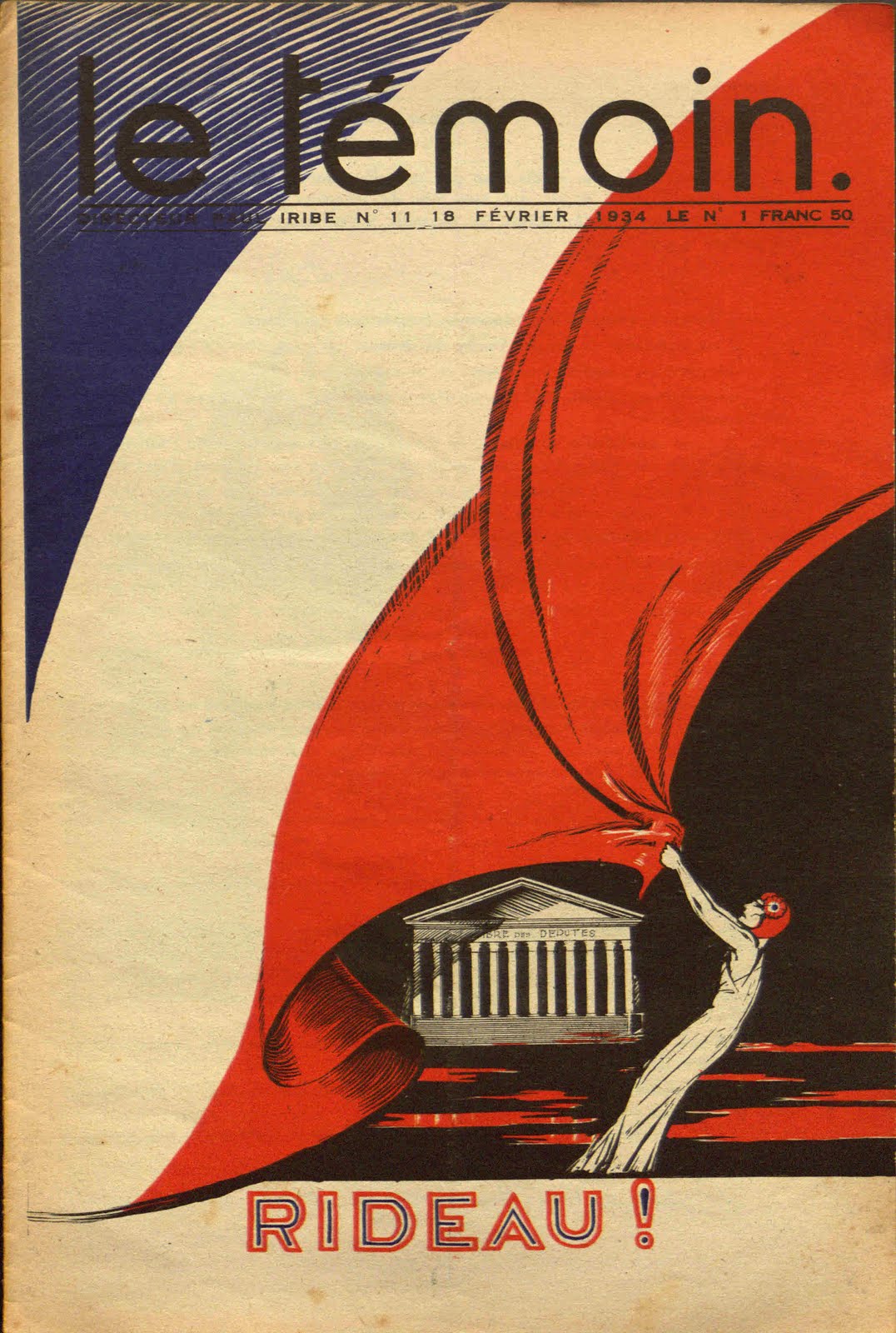

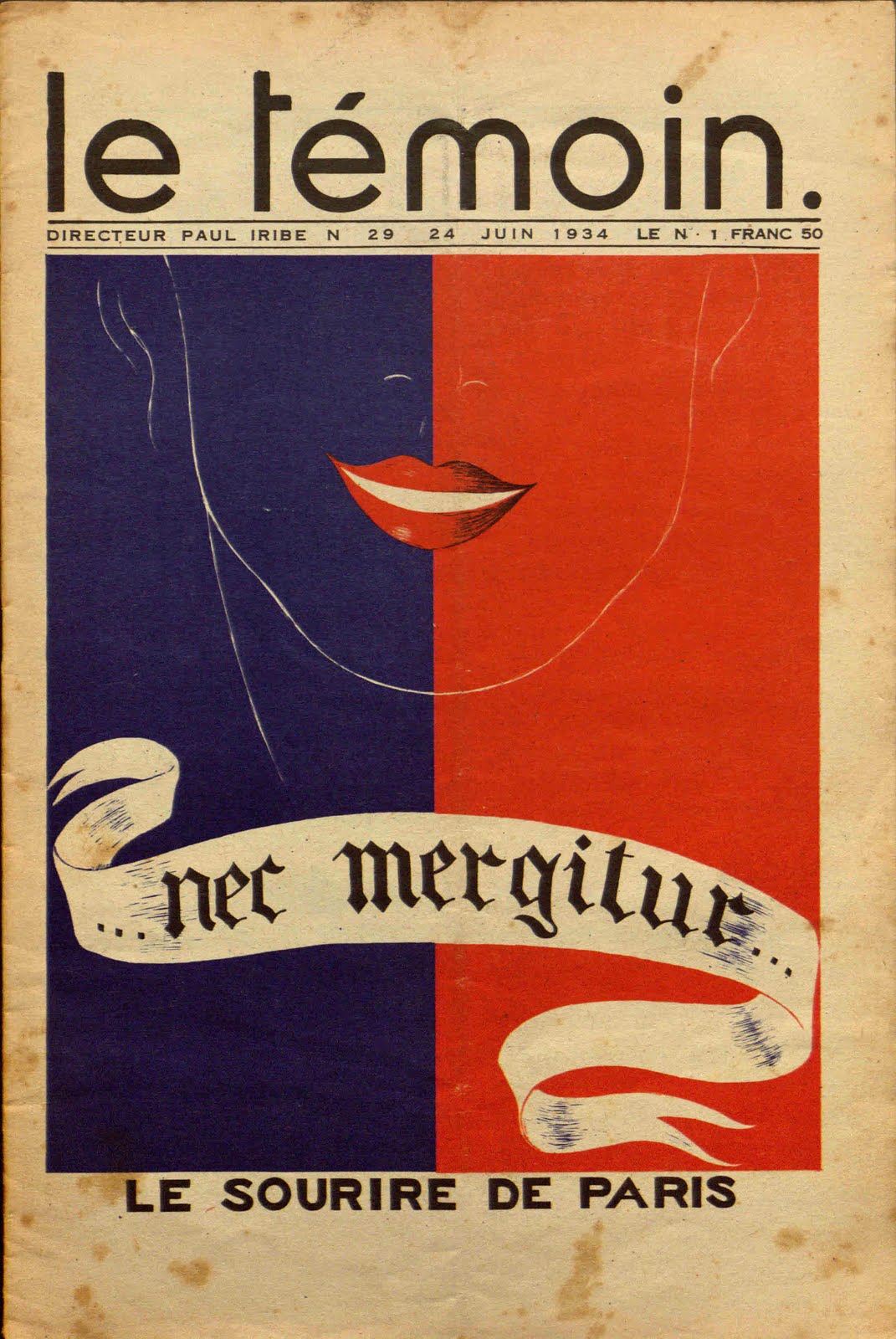

The French journal of political satire Le Témoin [The Witness], created by Paul Iribe, was not only a scathing report on every aspect of French political life, but also a magnificent display of Iribe’s artwork in its most mature state. The journal, while short-lived—it was distributed weekly from December 10, 1933, to June 30, 1935 (at a price of 1.50 FF), for a total of 69 issues—is noteworthy in its richness and complexity. Le Témoin stopped production during its regular summer hiatus at the end of June 1935, and was never to appear again, as Iribe died shortly before the fall issue was to be released.

The French journal of political satire Le Témoin [The Witness], created by Paul Iribe, was not only a scathing report on every aspect of French political life, but also a magnificent display of Iribe’s artwork in its most mature state. The journal, while short-lived—it was distributed weekly from December 10, 1933, to June 30, 1935 (at a price of 1.50 FF), for a total of 69 issues—is noteworthy in its richness and complexity. Le Témoin stopped production during its regular summer hiatus at the end of June 1935, and was never to appear again, as Iribe died shortly before the fall issue was to be released.

It is exceedingly difficult to find any issues of this fascinating journal, let alone the full run, which Brandeis is fortunate to hold. The journal will be of interest to researchers from a wide range of disciplines, including politics, French, history, fine arts and journalism.

The First Témoin

The 1933-1935 run of Le Témoin owned by Brandeis is in fact the second journal by that name put out by Iribe. Iribe published the first Témoin from 1906 to 1910. This original Témoin was the first of several newspapers and journals Iribe was to publish and to which he would contribute in his lifetime (including Le Temps, Le Cri de Paris, Le Canard Sauvage, L’Assiette Au Beurre and Le Mot). The 1906-1910 run is also a wonder of both political satire and art, and a myriad of famous artists (Hermann-Paul and Lyonel Feininger, among others) contributed to its pages, in contrast to the 1933-1935 run, which was illustrated solely by Iribe. It is unclear how many others contributed to the text of the two versions of Le Témoin, although it is quite clear that Iribe was the driving force behind both.

The 1933-1935 run of Le Témoin owned by Brandeis is in fact the second journal by that name put out by Iribe. Iribe published the first Témoin from 1906 to 1910. This original Témoin was the first of several newspapers and journals Iribe was to publish and to which he would contribute in his lifetime (including Le Temps, Le Cri de Paris, Le Canard Sauvage, L’Assiette Au Beurre and Le Mot). The 1906-1910 run is also a wonder of both political satire and art, and a myriad of famous artists (Hermann-Paul and Lyonel Feininger, among others) contributed to its pages, in contrast to the 1933-1935 run, which was illustrated solely by Iribe. It is unclear how many others contributed to the text of the two versions of Le Témoin, although it is quite clear that Iribe was the driving force behind both.

Paul Iribe

While Le Témoin alone can provide endless avenues for scholarship, it is worth noting that it cannot and probably should not be separated from its director and sole artist. Iribe, an intriguing figure in his own right, was known internationally for his early contributions to Art Deco, his illustrations for the fashion industry, his work with the film industry and, perhaps most famously, his love affair with Coco Chanel. Unfortunately, despite his renown during his lifetime, Iribe and Le Témoin have both been overlooked by the academic and artistic communities. In addition to the rich artistic and intellectual contributions of his published work, Iribe created advertising campaigns for, among other businesses, Ford Motors and Nicolas (the wine merchant); worked extensively with clothing designers, including Paul Poiret, where he first displayed his innovative style of depicting designs worn by active women in the midst of everyday activities, rather than by stiff and posed fashion models; had his own studio, where he focused on decorative art designs, including furniture and fabric; and moved briefly to the United States, where he worked as both costume and set designer on several Hollywood movies (including “The Ten Commandments” as artistic director for De Mille). The second appearance of Le Témoin can rightly be called the capstone to a varied and successful career.

While Le Témoin alone can provide endless avenues for scholarship, it is worth noting that it cannot and probably should not be separated from its director and sole artist. Iribe, an intriguing figure in his own right, was known internationally for his early contributions to Art Deco, his illustrations for the fashion industry, his work with the film industry and, perhaps most famously, his love affair with Coco Chanel. Unfortunately, despite his renown during his lifetime, Iribe and Le Témoin have both been overlooked by the academic and artistic communities. In addition to the rich artistic and intellectual contributions of his published work, Iribe created advertising campaigns for, among other businesses, Ford Motors and Nicolas (the wine merchant); worked extensively with clothing designers, including Paul Poiret, where he first displayed his innovative style of depicting designs worn by active women in the midst of everyday activities, rather than by stiff and posed fashion models; had his own studio, where he focused on decorative art designs, including furniture and fabric; and moved briefly to the United States, where he worked as both costume and set designer on several Hollywood movies (including “The Ten Commandments” as artistic director for De Mille). The second appearance of Le Témoin can rightly be called the capstone to a varied and successful career.

Le Témoin

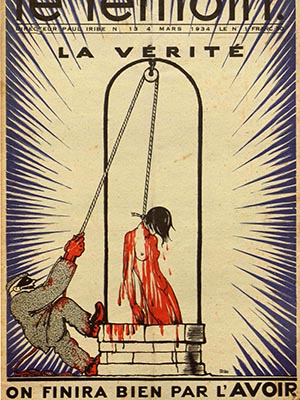

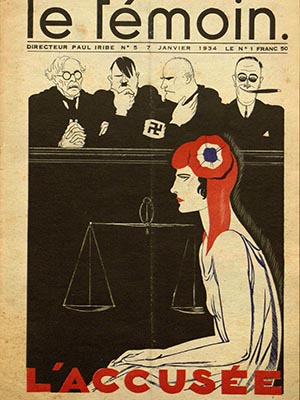

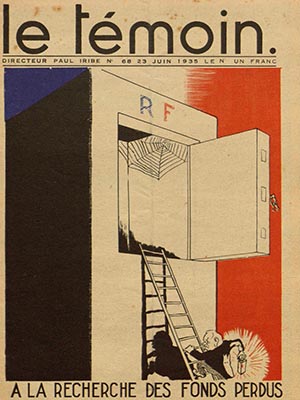

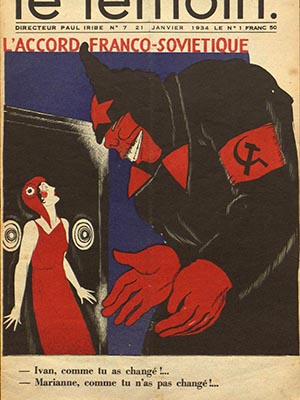

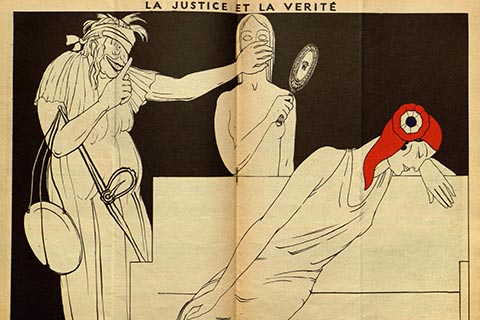

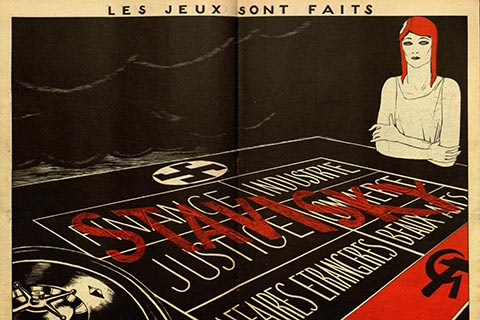

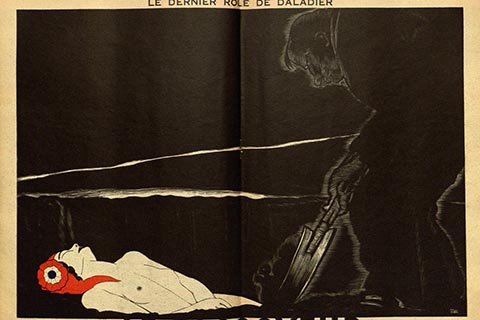

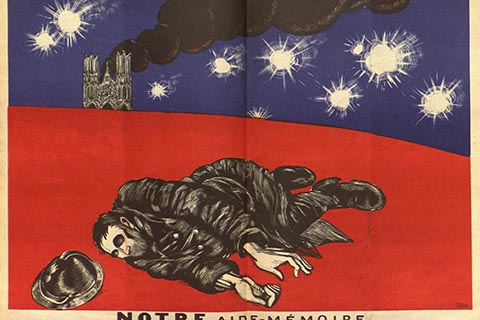

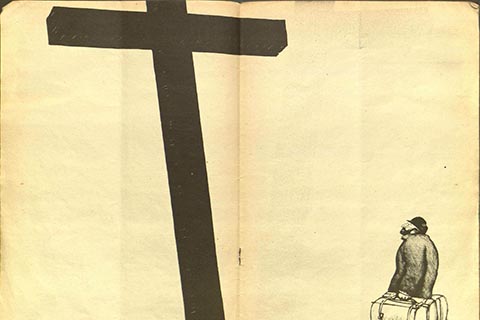

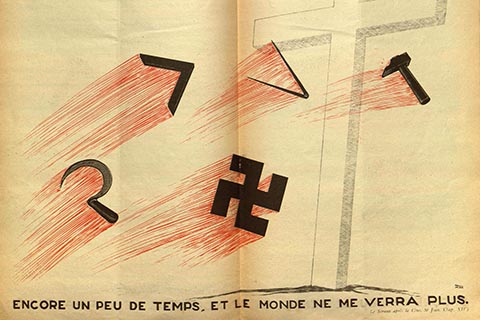

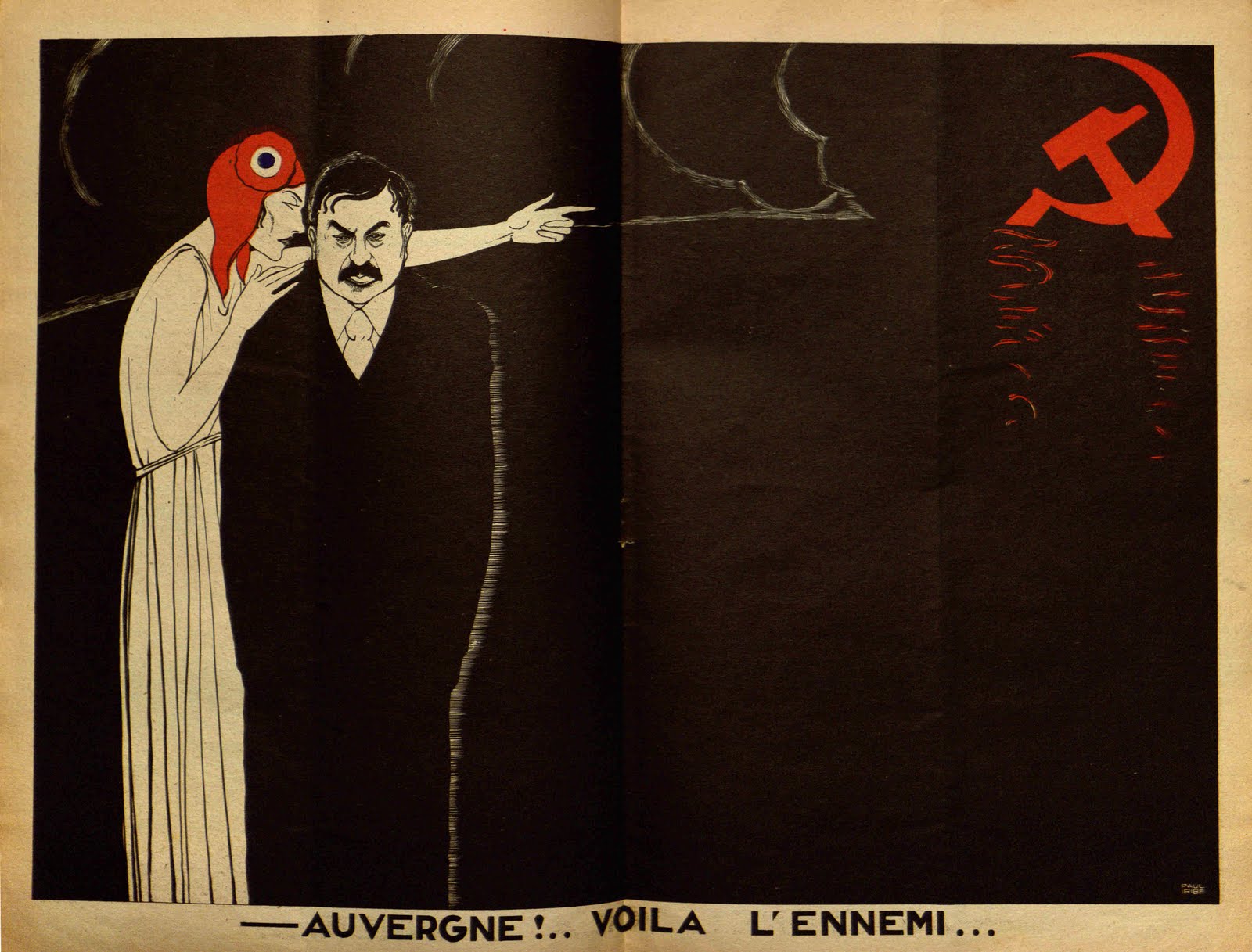

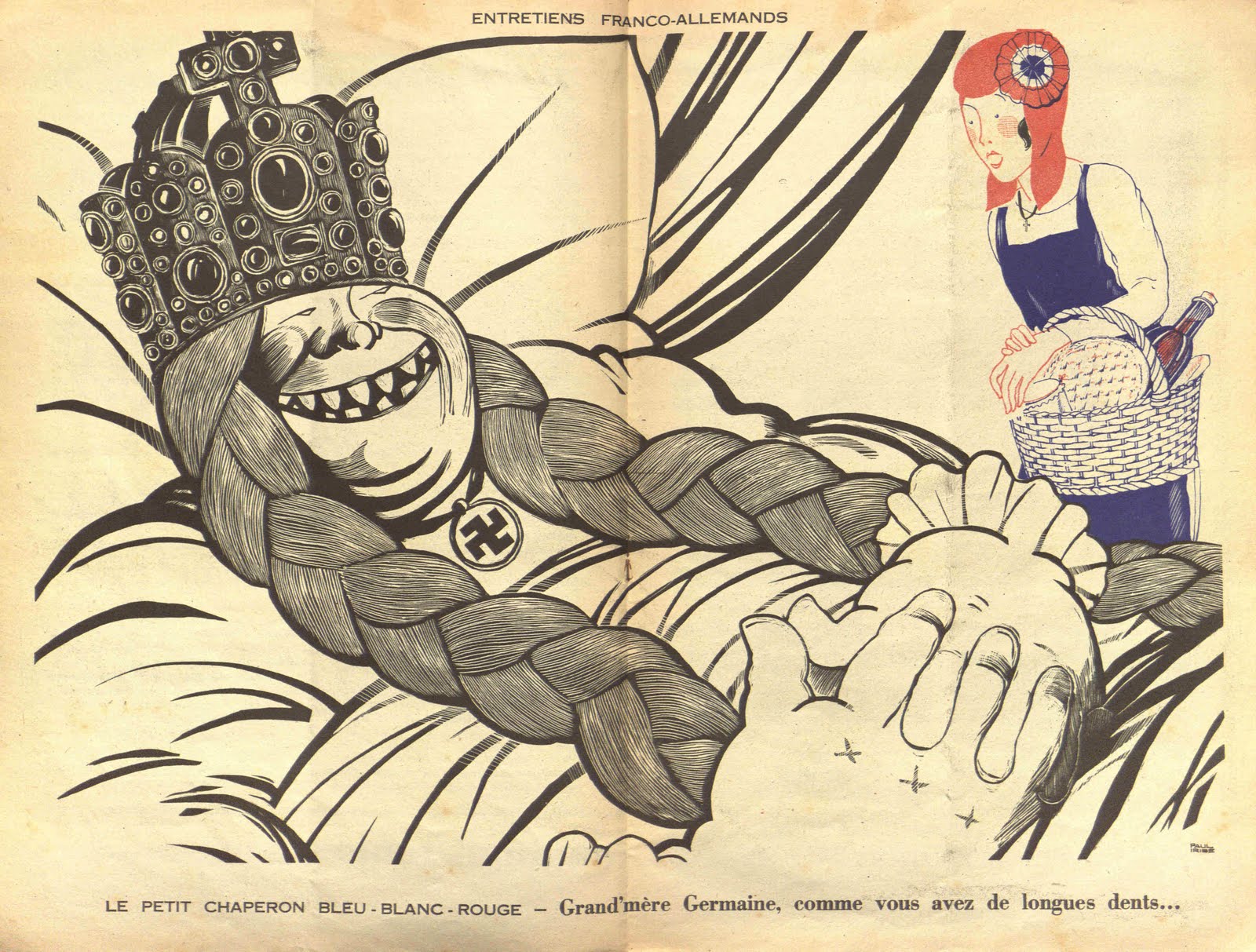

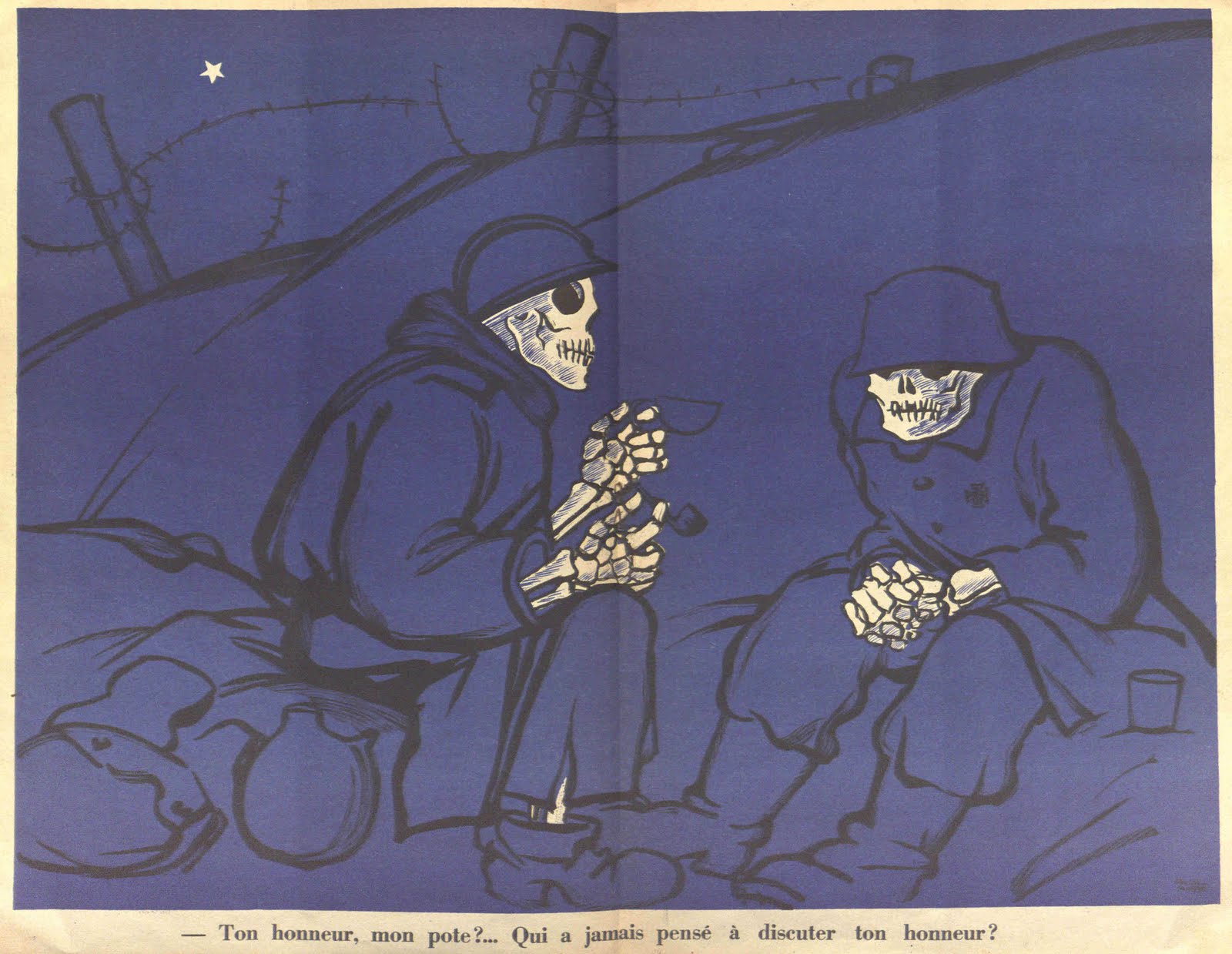

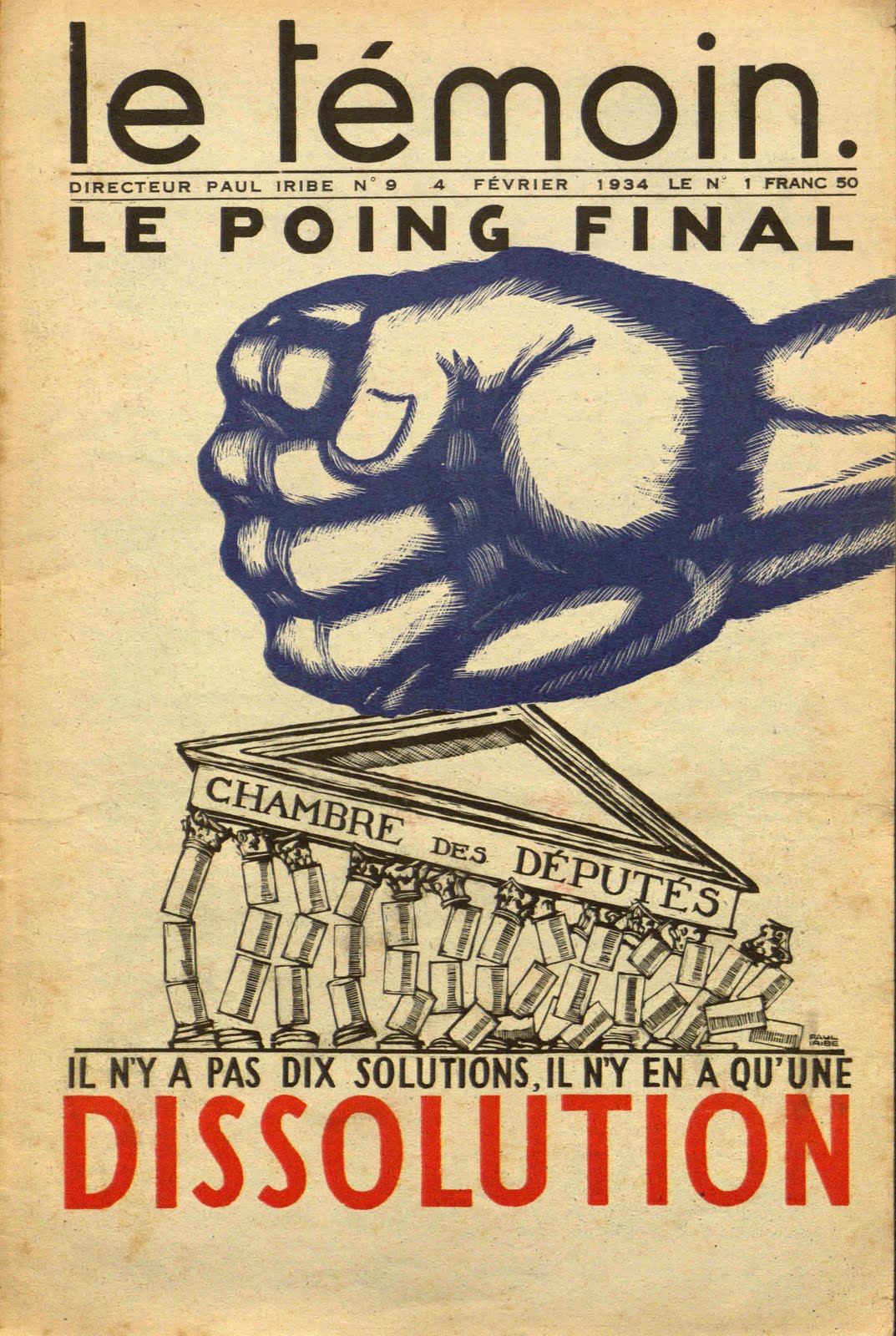

Le Témoin, unlike many other politically oriented papers of the period, is witty as well as cutting. Both the art and the text are intelligent, informed and cleverly designed. There are several basic patterns to Le Témoin: all of the major illustrations (of which there were at least three in every issue) were drawn in the blue, white and red of the French flag, with the major pieces located on the front and back covers and in the centerfold spread. The main recurring character is Marianne, the anthropomorphized symbol of the nation of France, who was drawn to resemble Coco Chanel in both physical appearance and design aesthetic. The front cover generally depicts the main focus of Iribe’s political critique for that week and is usually straightforward, topical and political-cartoon-esque in style. Highly stylized, and often shockingly stark, the centerfold illustration focuses on the larger issues faced by France at the time (Marianne features prominently in these) and was rendered in a more thought-provoking and punch-line-driven style. The back cover is always a plug for French industry; whether touting a particular French product, such as the silk of Lyon, or promoting the general importance and vitality of French business both large and small, these cover illustrations are the most blatantly propagandistic of Iribe’s work. The remaining illustrations Iribe drew in either black and white or using just two of the three tricolors. Recurring text pieces include the inside cover, which contains a letter from the editor/essay (unsigned after the first issue, which was signed only “Le Témoin”).

Le Témoin, unlike many other politically oriented papers of the period, is witty as well as cutting. Both the art and the text are intelligent, informed and cleverly designed. There are several basic patterns to Le Témoin: all of the major illustrations (of which there were at least three in every issue) were drawn in the blue, white and red of the French flag, with the major pieces located on the front and back covers and in the centerfold spread. The main recurring character is Marianne, the anthropomorphized symbol of the nation of France, who was drawn to resemble Coco Chanel in both physical appearance and design aesthetic. The front cover generally depicts the main focus of Iribe’s political critique for that week and is usually straightforward, topical and political-cartoon-esque in style. Highly stylized, and often shockingly stark, the centerfold illustration focuses on the larger issues faced by France at the time (Marianne features prominently in these) and was rendered in a more thought-provoking and punch-line-driven style. The back cover is always a plug for French industry; whether touting a particular French product, such as the silk of Lyon, or promoting the general importance and vitality of French business both large and small, these cover illustrations are the most blatantly propagandistic of Iribe’s work. The remaining illustrations Iribe drew in either black and white or using just two of the three tricolors. Recurring text pieces include the inside cover, which contains a letter from the editor/essay (unsigned after the first issue, which was signed only “Le Témoin”).

Now we come to the crux of Le Témoin’s political message. Iribe most often depicted Marianne (i.e., France) in relation to the various leaders of the major Western powers, particularly the United States (Franklin D. Roosevelt), Great Britain (Ramsay MacDonald), Germany (Adolph Hitler), Russia (Joseph Stalin) and Italy (Benito Mussolini). These relationships lay at the core of Iribe’s political agenda, which was distinctly and perhaps myopically nationalistic. Iribe perceived France as allowing itself to be bullied by these other countries, and his nationalism took on a particular cast: less about the superiority of the French nation (its greatness, certainly), and more about the importance of its independence and strength in the face of overbearing foreign influence. Interestingly, Iribe tended only to mock these foreign heads of state qua leaders, as political players rather than as stand-ins for the nations they ran. And while Iribe was not above satirizing these men, he reserved his sharpest critiques for France’s leaders, whom he saw as capitulating to the hegemony of these other nations and leading France into a spiral of weakness and subjugation.

Now we come to the crux of Le Témoin’s political message. Iribe most often depicted Marianne (i.e., France) in relation to the various leaders of the major Western powers, particularly the United States (Franklin D. Roosevelt), Great Britain (Ramsay MacDonald), Germany (Adolph Hitler), Russia (Joseph Stalin) and Italy (Benito Mussolini). These relationships lay at the core of Iribe’s political agenda, which was distinctly and perhaps myopically nationalistic. Iribe perceived France as allowing itself to be bullied by these other countries, and his nationalism took on a particular cast: less about the superiority of the French nation (its greatness, certainly), and more about the importance of its independence and strength in the face of overbearing foreign influence. Interestingly, Iribe tended only to mock these foreign heads of state qua leaders, as political players rather than as stand-ins for the nations they ran. And while Iribe was not above satirizing these men, he reserved his sharpest critiques for France’s leaders, whom he saw as capitulating to the hegemony of these other nations and leading France into a spiral of weakness and subjugation.

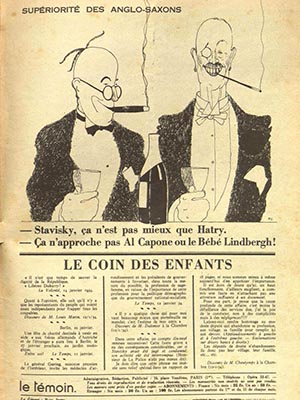

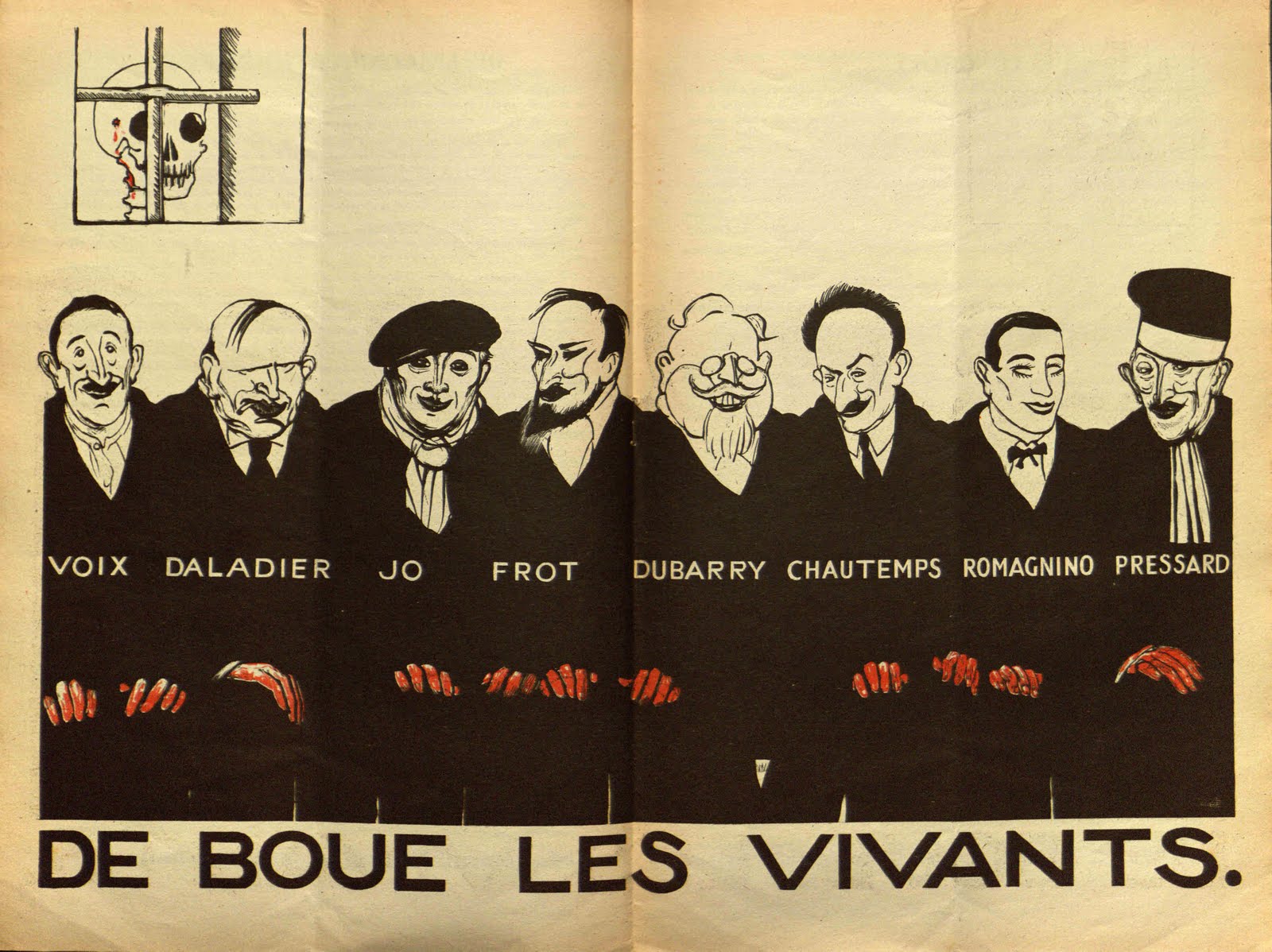

Iribe also had much to say on the domestic front, often about the way in which the state and national infrastructure were being run—recurring themes including the misery inflicted on French people by the “taxman” and the embarrassing obsolescence of the rail system. The French government, its ineptitude and its weakness in the face of foreign intervention, and the specters of Communism, Fascism and Freemasonry were all constant grist for Iribe’s mill, and Leon Blum and the conspirators of the Stavisky Affair hold a vaunted place throughout Le Témoin’s run.

Iribe also had much to say on the domestic front, often about the way in which the state and national infrastructure were being run—recurring themes including the misery inflicted on French people by the “taxman” and the embarrassing obsolescence of the rail system. The French government, its ineptitude and its weakness in the face of foreign intervention, and the specters of Communism, Fascism and Freemasonry were all constant grist for Iribe’s mill, and Leon Blum and the conspirators of the Stavisky Affair hold a vaunted place throughout Le Témoin’s run.

But in a small piece at the end of the third issue, Iribe offered his readers a close look into his political mind. In this piece, Iribe addressed several letters received from readers, calling for him to denounce the Jewish population of France as outsiders. Iribe responded in a tightly worded, unapologetic note that any man who was willing to take up arms on behalf of France was his “brother,” and as such he had no problem with Jews. This brief note of Iribe’s seems a perfect exemplar of the man’s nationalistic stance. Unsentimental and unprejudiced, his nationalism was positive rather than negative in nature. Iribe focused his energy and concern on what was good about France, rather than on what was wrong with other countries. And while he never seemed to make a sustained case for inclusion, Iribe certainly seemed to find it a waste of time to bother with exclusion. If you would fight for France, how were you not a Frenchman?

But in a small piece at the end of the third issue, Iribe offered his readers a close look into his political mind. In this piece, Iribe addressed several letters received from readers, calling for him to denounce the Jewish population of France as outsiders. Iribe responded in a tightly worded, unapologetic note that any man who was willing to take up arms on behalf of France was his “brother,” and as such he had no problem with Jews. This brief note of Iribe’s seems a perfect exemplar of the man’s nationalistic stance. Unsentimental and unprejudiced, his nationalism was positive rather than negative in nature. Iribe focused his energy and concern on what was good about France, rather than on what was wrong with other countries. And while he never seemed to make a sustained case for inclusion, Iribe certainly seemed to find it a waste of time to bother with exclusion. If you would fight for France, how were you not a Frenchman?

The full run of the 1933-1935 Le Témoin documents a vital moment in the history of France and the Western world. Its commentary and illustrations are not only stunning and evocative but provide an additional view into an arena in which much of the world was lining up for the major conflict to come.

The full run of the 1933-1935 Le Témoin documents a vital moment in the history of France and the Western world. Its commentary and illustrations are not only stunning and evocative but provide an additional view into an arena in which much of the world was lining up for the major conflict to come.

For further information

Raymond Bachollet, Daniel Bordet, Anne-Claude Lelieur. Paul Iribe. Art Books Intl Ltd, 1982.

Raymond Bachollet, Daniel Bordet, Anne-Claude Lelieur. Paul Iribe. Art Books Intl Ltd, 1982.

Raymond Bachollet, Daniel Bordet, Anne-Claude Lelieur. Paul Iribe: precurseur de l’art deco. Art Books Intl Ltd, 1983.