World War I and World War II Propaganda Posters Collection

September 22, 2008

Description by Aaron Wirth, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in the Comparative History Program

Photos by Maggie McNeely

Brandeis University’s World War I and World War II Propaganda Posters Collection includes nearly a hundred different images illustrating scores of different wartime topics. Initially inspired by the examples in western European countries, the creation and production of visually stunning, applicable pictorial publicity immediately gathered a substantial level of artistic involvement and industrial application in the United States.

Brandeis University’s World War I and World War II Propaganda Posters Collection includes nearly a hundred different images illustrating scores of different wartime topics. Initially inspired by the examples in western European countries, the creation and production of visually stunning, applicable pictorial publicity immediately gathered a substantial level of artistic involvement and industrial application in the United States.

World War I created greater demands on both physical and human resources on an international scale than had ever been thought necessary before. The war was first and foremost one of industrial competition, in which the manufacture of arms and munitions became essential; it was a war in which recent inventions like the airplane and the machine gun were used with deadly effect, and a new invention, the tank, was introduced. Additionally, it was necessary to engage the will of the entire population. Information pertinent to the war was needed and had to be supplied by traditional means, such as newspapers, proclamations and notices; newer media were also required, like film and pictorial posters, which were able to persuade as well as inform. Gaining popularity quickly, by 1914 posters were as well established as press advertising. To be sure, it would have been folly for governments to have neglected such a successful medium.

World War I created greater demands on both physical and human resources on an international scale than had ever been thought necessary before. The war was first and foremost one of industrial competition, in which the manufacture of arms and munitions became essential; it was a war in which recent inventions like the airplane and the machine gun were used with deadly effect, and a new invention, the tank, was introduced. Additionally, it was necessary to engage the will of the entire population. Information pertinent to the war was needed and had to be supplied by traditional means, such as newspapers, proclamations and notices; newer media were also required, like film and pictorial posters, which were able to persuade as well as inform. Gaining popularity quickly, by 1914 posters were as well established as press advertising. To be sure, it would have been folly for governments to have neglected such a successful medium.

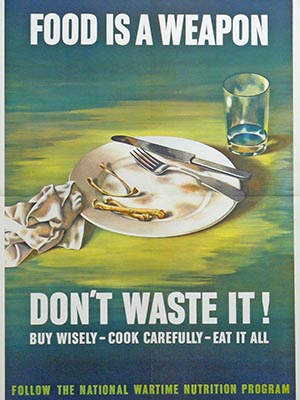

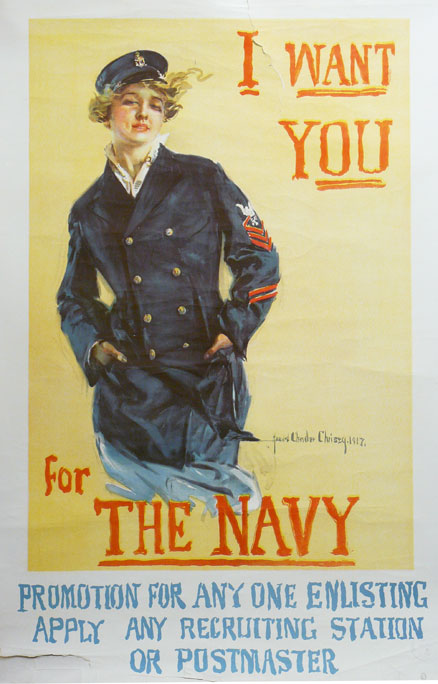

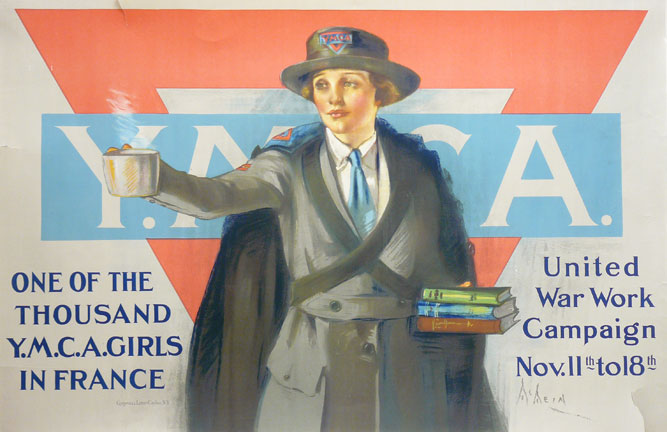

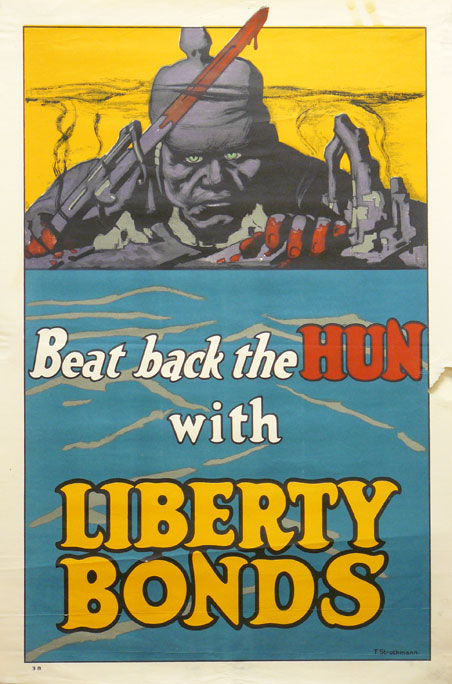

Indeed, governments exploited posters. They were used to call for recruits (“Join the Navy: The Service for Fighting Men”), request loans, make national policies acceptable, spur industrial effort, channel emotions such as courage or hate (“Beat back the Hun”), urge conservation of resources (“Food is a Weapon: Don’t Waste It!”), and inform the public of food necessities and food substitutes. Charitable organizations, such as the Red Cross, the YMCA and the YWCA, requested financial support for fighting men and civilian casualties. The posters in Brandeis Special Collections include outstanding examples of all these types, as well as some more specialized posters, such as “All Together: Enlist in the Navy,” which depicts sailors from different countries.

Indeed, governments exploited posters. They were used to call for recruits (“Join the Navy: The Service for Fighting Men”), request loans, make national policies acceptable, spur industrial effort, channel emotions such as courage or hate (“Beat back the Hun”), urge conservation of resources (“Food is a Weapon: Don’t Waste It!”), and inform the public of food necessities and food substitutes. Charitable organizations, such as the Red Cross, the YMCA and the YWCA, requested financial support for fighting men and civilian casualties. The posters in Brandeis Special Collections include outstanding examples of all these types, as well as some more specialized posters, such as “All Together: Enlist in the Navy,” which depicts sailors from different countries.

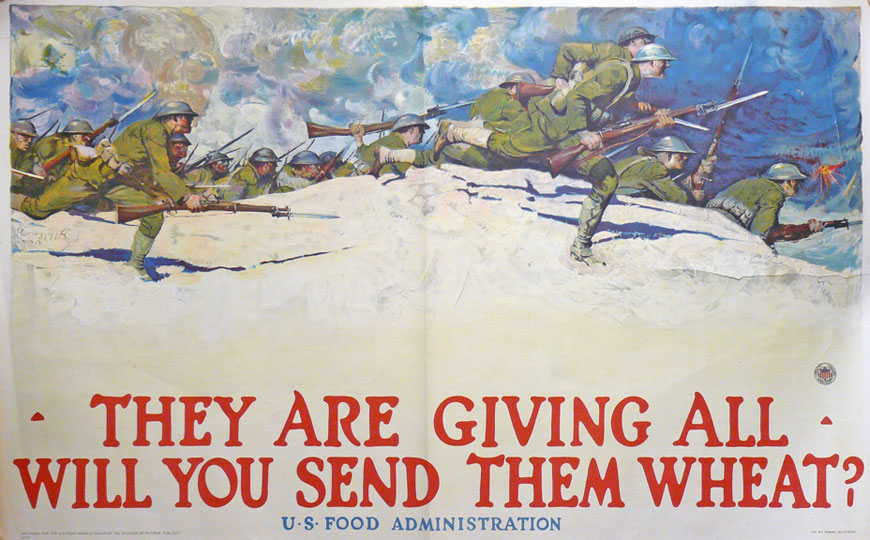

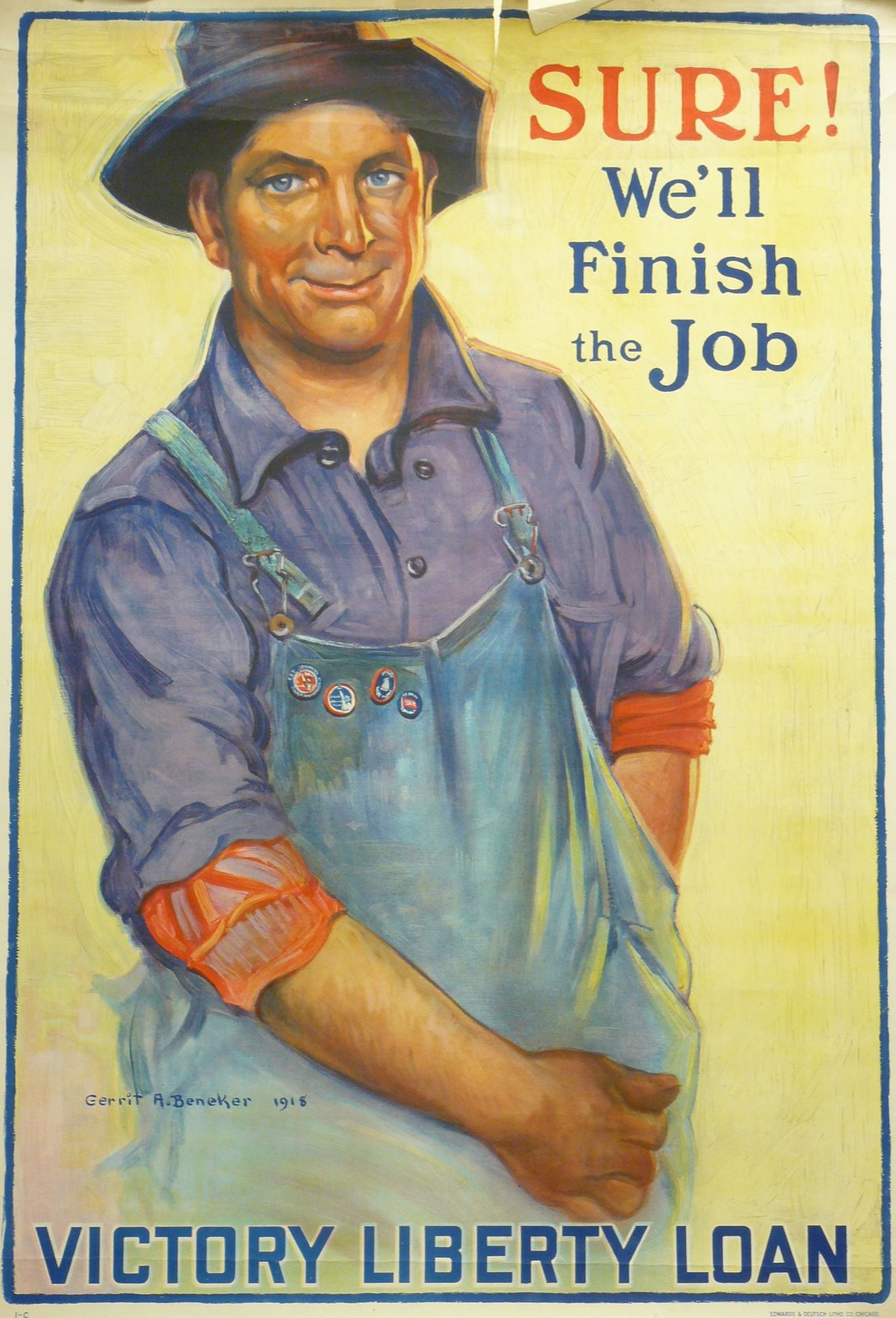

As befits a democratic nation, the majority of the images were aimed at ordinary citizens, reflecting back to them their strength, thriftiness and common humanity—all of which encouraged the viewer to identify with the down-to-earth attitude of the laborer, who would work hard and spare a portion of his earnings for the war effort. In 1919, The Poster Souvenir Edition interviewed Gerrit A. Beneker about his poster “Sure! We’ll finish the job!” for Victory Liberty Loan. He said of the painting, “I took a working man as my hero [who was] known to every man, woman and child in the country.” Also, food administration posters made a play on the sacrifices of the troops in Europe to motivate the people at home to contribute as much as they could spare (“They are giving all. Will you send them wheat?”). Visually and textually, the war effort at home was likened to that of the front. Men and women were portrayed as, and encouraged to be, active citizens.

As befits a democratic nation, the majority of the images were aimed at ordinary citizens, reflecting back to them their strength, thriftiness and common humanity—all of which encouraged the viewer to identify with the down-to-earth attitude of the laborer, who would work hard and spare a portion of his earnings for the war effort. In 1919, The Poster Souvenir Edition interviewed Gerrit A. Beneker about his poster “Sure! We’ll finish the job!” for Victory Liberty Loan. He said of the painting, “I took a working man as my hero [who was] known to every man, woman and child in the country.” Also, food administration posters made a play on the sacrifices of the troops in Europe to motivate the people at home to contribute as much as they could spare (“They are giving all. Will you send them wheat?”). Visually and textually, the war effort at home was likened to that of the front. Men and women were portrayed as, and encouraged to be, active citizens.

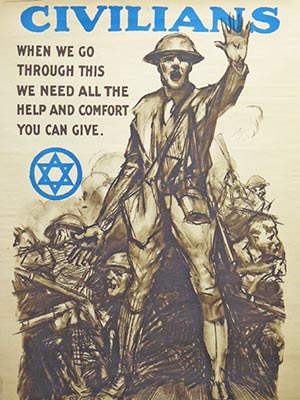

It must be noted, however, that the United States was an immigrant country, and notions of the nation were potentially unstable. The government therefore promoted national unity through labor, service and the family in slogans such as “Together we win.” Additionally, some posters specifically appealed to immigrants themselves who were asked help in the cause. For example, C.E. Chambers depicts newly arriving immigrants via boat, gazing at their new homeland with the Statue of Liberty in the background and a red, white and blue rainbow arching over the golden silhouette of Manhattan. The most striking aspect of the American poster, however, is the Yiddish text. The translation is as follows:

It must be noted, however, that the United States was an immigrant country, and notions of the nation were potentially unstable. The government therefore promoted national unity through labor, service and the family in slogans such as “Together we win.” Additionally, some posters specifically appealed to immigrants themselves who were asked help in the cause. For example, C.E. Chambers depicts newly arriving immigrants via boat, gazing at their new homeland with the Statue of Liberty in the background and a red, white and blue rainbow arching over the golden silhouette of Manhattan. The most striking aspect of the American poster, however, is the Yiddish text. The translation is as follows:

“Food will win the war! You came here to find freedom. Now we must help to defend her. We must supply the Allies with wheat. Let nothing go to waste. United States Food Administration.”

The war effort was often articulated within a language of freedom, progress and happiness.

The war effort was often articulated within a language of freedom, progress and happiness.

In the United States, certain illustrators were so popular that they played a dominant role in the production of war posters even though they had not previously been identified with poster art. For example, artist James Montgomery Flagg created a self-portrait for his depiction of Uncle Sam, one of the most widely reproduced images in history (over five million copies are said to have been printed). Cheerful glamour was contributed by Howard Chandler Christy, whose “Christy Girl” enticed men to fight or to buy liberty bonds (“I Want You for the Navy”). In addition, the poster collection at Brandeis includes such other famous artists as Adolph Treidler, Edwin Howland Blashfield, Harrison Fisher, Casper Emerson Jr., Henry Patrick Raleigh and Haskell Coffin, among others.

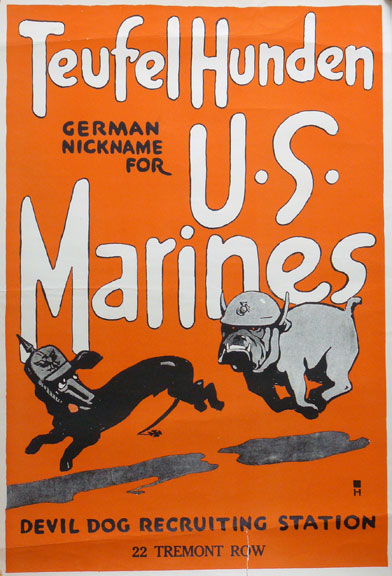

Although the posters are now seen out of their original context, it should be noted that they were often used as part of a bigger campaign, together with personal appearances by politicians and celebrities, pageants, press advertisings, flag days and the introduction of popular songs, as well as in oversized formats that occupied billboards (such as “Joan of Arc Saved France” and “Teufel Hunden,” seen here).

Although the posters are now seen out of their original context, it should be noted that they were often used as part of a bigger campaign, together with personal appearances by politicians and celebrities, pageants, press advertisings, flag days and the introduction of popular songs, as well as in oversized formats that occupied billboards (such as “Joan of Arc Saved France” and “Teufel Hunden,” seen here).

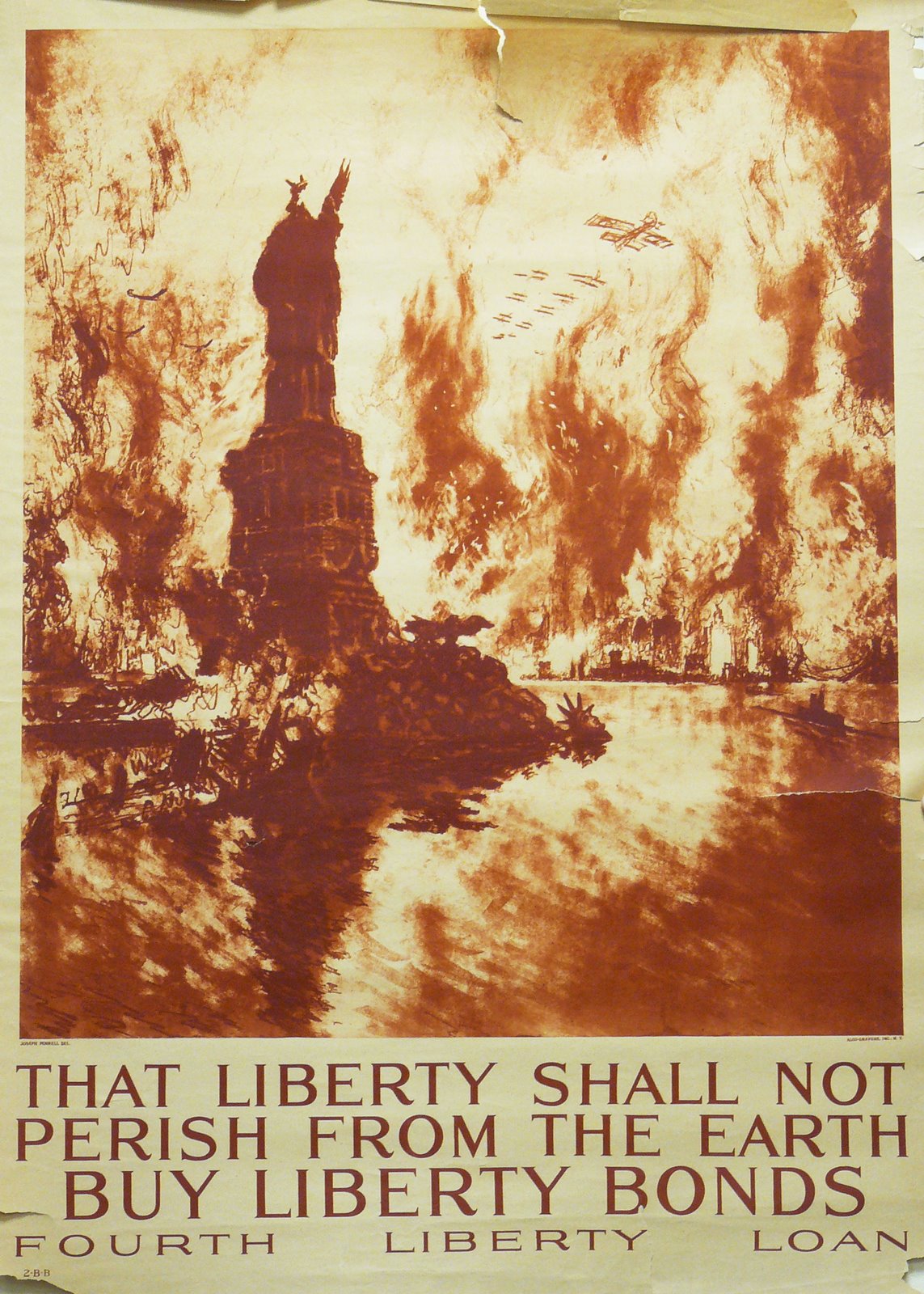

Nevertheless, to look at a group of war posters together, as in this Spotlight, is to get an understanding of the immediate response they inspired. Their overzealous patriotism would not be possible today; personal appeals—“I want you,” “What did you do?”—were widespread. These posters, too, give a many-sided image of war and its effects: the fatigued soldier, the despair of victims and apocalyptic scenes of cities such as in Joseph Pennell’s painting “That Liberty Shall Not Perish From The Earth: Buy Liberty Bonds—Fourth Liberty Loan,” which shows enemy fighter planes bombing New York harbor and decapitating the Statue of Liberty. The aim of these posters was to show the disruption of normal, everyday life.

Nevertheless, to look at a group of war posters together, as in this Spotlight, is to get an understanding of the immediate response they inspired. Their overzealous patriotism would not be possible today; personal appeals—“I want you,” “What did you do?”—were widespread. These posters, too, give a many-sided image of war and its effects: the fatigued soldier, the despair of victims and apocalyptic scenes of cities such as in Joseph Pennell’s painting “That Liberty Shall Not Perish From The Earth: Buy Liberty Bonds—Fourth Liberty Loan,” which shows enemy fighter planes bombing New York harbor and decapitating the Statue of Liberty. The aim of these posters was to show the disruption of normal, everyday life.

Most important, these posters are valuable as historical documents. One’s idea of World War I is darkly colored by knowledge of corpse-ridden battlefields and the appalling conditions of trench warfare. These posters give some flavor to the period as it was experienced by civilians. If one is astonished at the psychological approach of recruiting posters in this period, that is primarily due to a historical misunderstanding that posters can help to correct. In these posters exist old feelings one could not know in any other way.

Most important, these posters are valuable as historical documents. One’s idea of World War I is darkly colored by knowledge of corpse-ridden battlefields and the appalling conditions of trench warfare. These posters give some flavor to the period as it was experienced by civilians. If one is astonished at the psychological approach of recruiting posters in this period, that is primarily due to a historical misunderstanding that posters can help to correct. In these posters exist old feelings one could not know in any other way.

Amazingly, although the United States entered the war rather late—April of 1917—it produced more propaganda posters than any other single nation. During the interwar period and World War II, other countries, particularly Germany, were inspired by American propaganda posters due to their positive effect on the nation’s citizens. Interestingly, the latter part of the 20th century saw manufactured propaganda posters that were used to protest wars as much as they were used to support them, if not more. Even today, the poster is the exemplary medium that appeals to the most modern phenomenon: the masses.

Amazingly, although the United States entered the war rather late—April of 1917—it produced more propaganda posters than any other single nation. During the interwar period and World War II, other countries, particularly Germany, were inspired by American propaganda posters due to their positive effect on the nation’s citizens. Interestingly, the latter part of the 20th century saw manufactured propaganda posters that were used to protest wars as much as they were used to support them, if not more. Even today, the poster is the exemplary medium that appeals to the most modern phenomenon: the masses.