Marcel Proust Letters

September 4, 2012

Description by Hollie Harder, Associate Professor of French and Francophone Studies, and Director of the Language Programs, Romance Studies

In search of letters by Marcel Proust at Brandeis University? Mais oui!

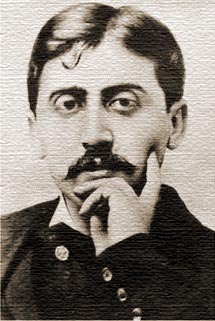

Among the gems of literary history that are housed in the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department are 23 original letters penned between 1913 and 1916 by Marcel Proust, the writer many consider the greatest French novelist of the twentieth century. Although the letters in the Brandeis collection represent only a fraction of those that Proust wrote during this pivotal period, they are among some of the most important documents in the publication history of his 3,000-page tome, À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time). The letters articulate fundamental concerns that he had about the editing process, and, in turn, they serve to illuminate larger dimensions of Proust’s novel and his literary aesthetics. Unlike the manuscript pages for Proust grand novel, which are located in the Bibliothèque Nationale (Richelieu) in Paris, these letters are readily accessible to all readers. No need to prove the relevance of this correspondence to a research project or provide academic credentials. Interest in these intriguing letters will suffice.

Among the gems of literary history that are housed in the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department are 23 original letters penned between 1913 and 1916 by Marcel Proust, the writer many consider the greatest French novelist of the twentieth century. Although the letters in the Brandeis collection represent only a fraction of those that Proust wrote during this pivotal period, they are among some of the most important documents in the publication history of his 3,000-page tome, À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time). The letters articulate fundamental concerns that he had about the editing process, and, in turn, they serve to illuminate larger dimensions of Proust’s novel and his literary aesthetics. Unlike the manuscript pages for Proust grand novel, which are located in the Bibliothèque Nationale (Richelieu) in Paris, these letters are readily accessible to all readers. No need to prove the relevance of this correspondence to a research project or provide academic credentials. Interest in these intriguing letters will suffice.

The Proust letters at Brandeis date from February 1913, the year that saw the publication of Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way), the first volume of the Search. They include key negotiations with his first editor and publisher, Bernard Grasset, and they reveal Proust’s preoccupations with the shape and format of his novel, the reception that he envisioned for his book, and the truths that he hoped readers would discover within its pages. In addition, the letters bear witness to ups and downs in the personal and professional relationship between Proust and Grasset. The opening and closing formulas that Proust uses in his written exchanges with Grasset from 1913 to 1916 reflect the evolution of their partnership: we see the happy beginnings of their collaboration and subsequently the gradual slide toward distanced politeness that precedes the dissolution of their business dealings. The last letter in the Brandeis collection dates from 1916, the year that Proust leaves Éditions Grasset for Gaston Gallimard's NRF (Nouvelle Revue Française). The correspondence between Proust and Grasset is of particular interest now, given that 2013 marks the centennial of the publication of Swann.

The Proust letters at Brandeis date from February 1913, the year that saw the publication of Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way), the first volume of the Search. They include key negotiations with his first editor and publisher, Bernard Grasset, and they reveal Proust’s preoccupations with the shape and format of his novel, the reception that he envisioned for his book, and the truths that he hoped readers would discover within its pages. In addition, the letters bear witness to ups and downs in the personal and professional relationship between Proust and Grasset. The opening and closing formulas that Proust uses in his written exchanges with Grasset from 1913 to 1916 reflect the evolution of their partnership: we see the happy beginnings of their collaboration and subsequently the gradual slide toward distanced politeness that precedes the dissolution of their business dealings. The last letter in the Brandeis collection dates from 1916, the year that Proust leaves Éditions Grasset for Gaston Gallimard's NRF (Nouvelle Revue Française). The correspondence between Proust and Grasset is of particular interest now, given that 2013 marks the centennial of the publication of Swann.

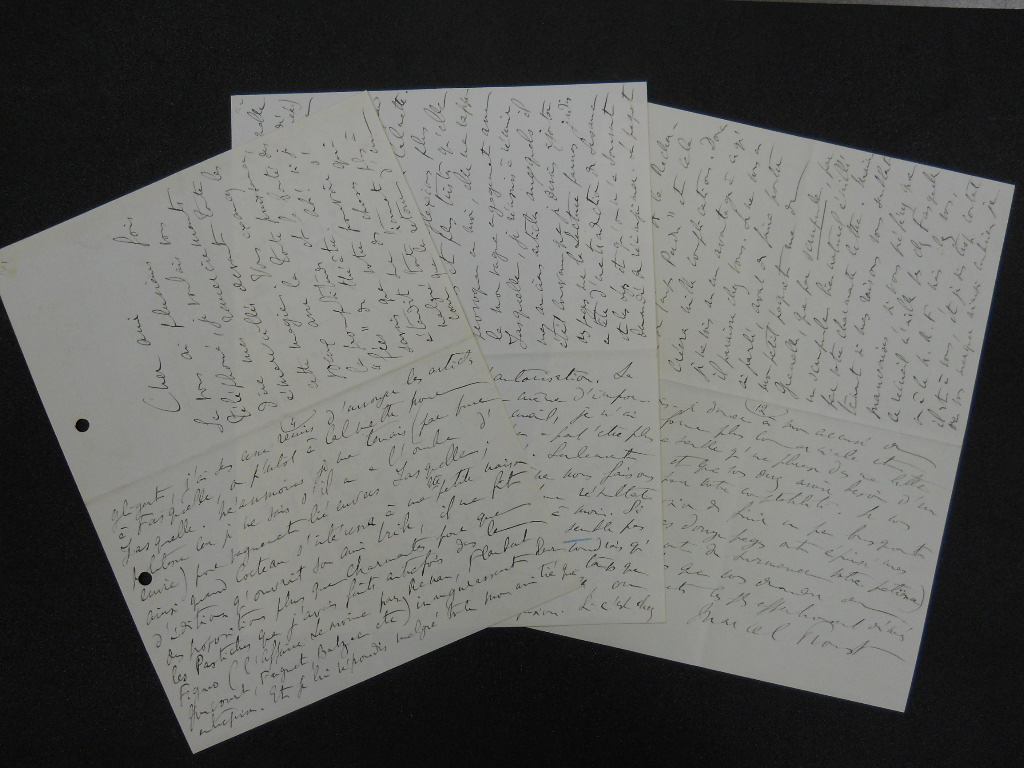

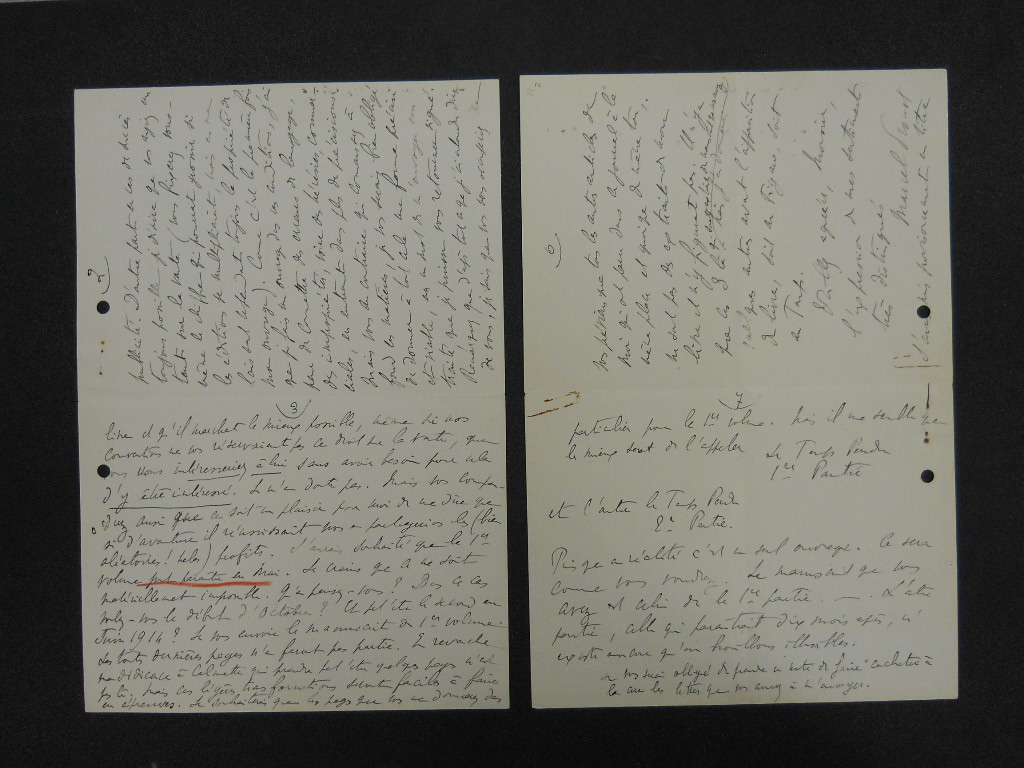

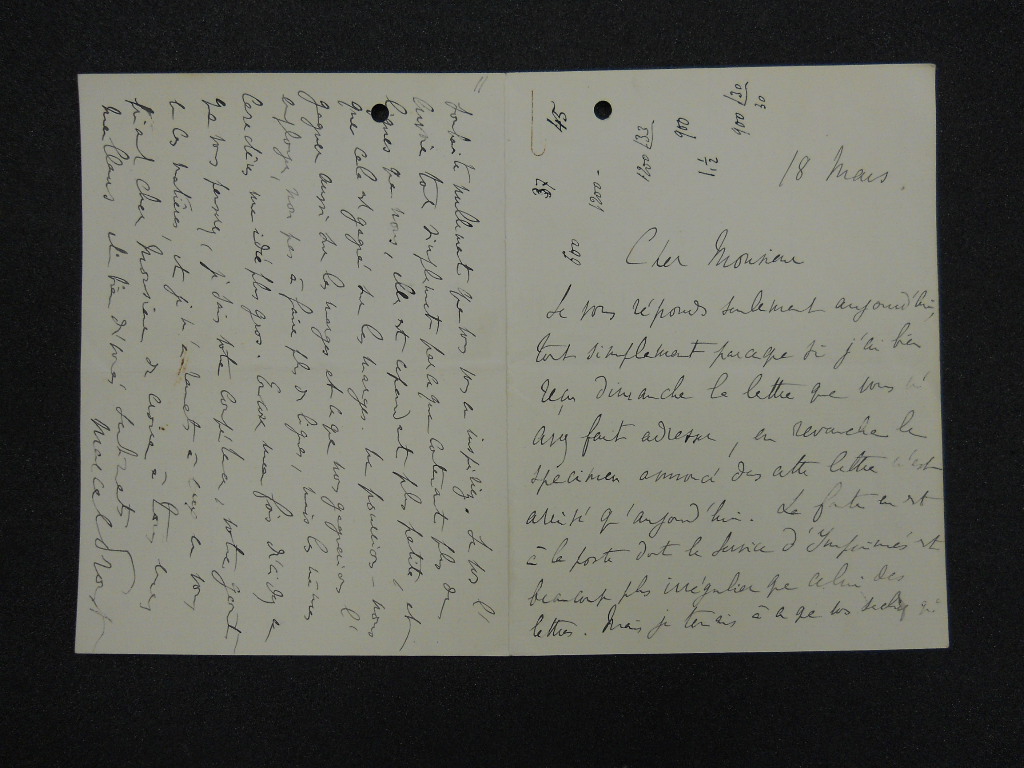

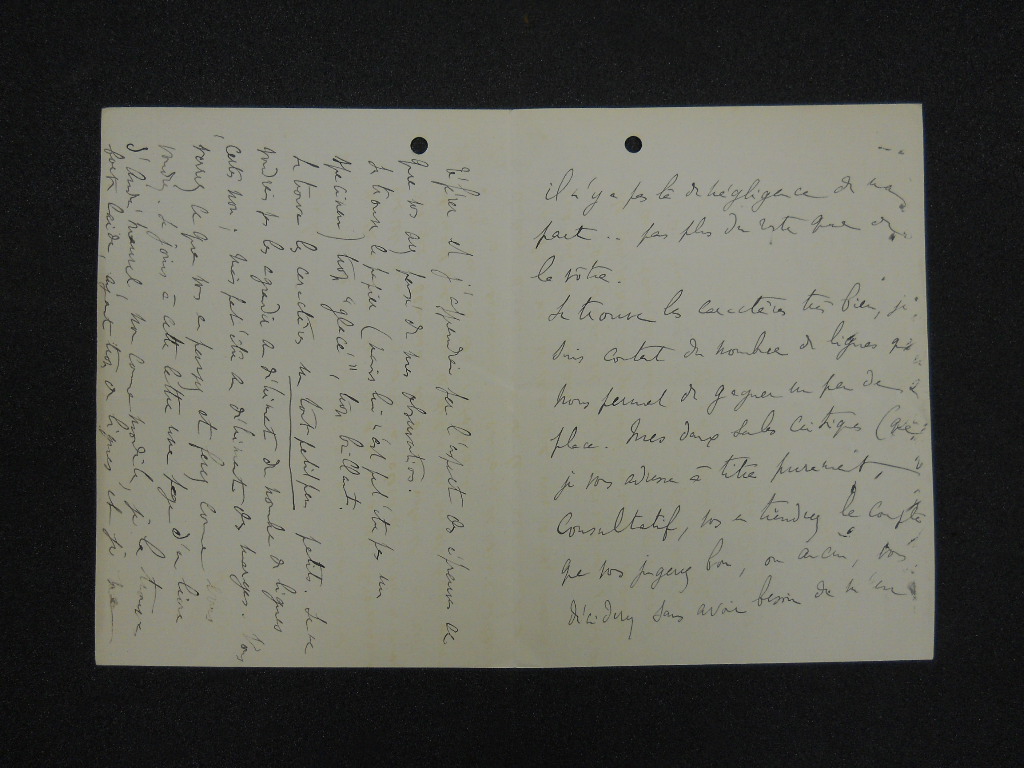

Of the 23 letters that Brandeis possesses, all are handwritten by Proust on cream-colored laid paper, except for one, which is typed on stationery bearing the letterhead of the French newspaper Le Figaro. Twenty-two are addressed to Grasset, and one letter, dating from April 1914, is addressed to Louis Brun, Grasset’s friend and business partner. Although twenty of the letters are undated, they appear—with dates—in the writer’s correspondence that was published (in French) between 1971 and 1992 by the renowned Proust scholar Philip Kolb. Three of the letters at Brandeis are accompanied by typed transcriptions in French, and one of those also includes a typed English translation. Moreover, seven letters in the Brandeis collection appear in translation in Kolb’s Selected Letters. These English versions are a testimony to the challenges of reconstructing the chronology of Proust's communications; the dates for two of the French transcriptions differ from those of Kolb's corresponding translations.

Of the 23 letters that Brandeis possesses, all are handwritten by Proust on cream-colored laid paper, except for one, which is typed on stationery bearing the letterhead of the French newspaper Le Figaro. Twenty-two are addressed to Grasset, and one letter, dating from April 1914, is addressed to Louis Brun, Grasset’s friend and business partner. Although twenty of the letters are undated, they appear—with dates—in the writer’s correspondence that was published (in French) between 1971 and 1992 by the renowned Proust scholar Philip Kolb. Three of the letters at Brandeis are accompanied by typed transcriptions in French, and one of those also includes a typed English translation. Moreover, seven letters in the Brandeis collection appear in translation in Kolb’s Selected Letters. These English versions are a testimony to the challenges of reconstructing the chronology of Proust's communications; the dates for two of the French transcriptions differ from those of Kolb's corresponding translations.

Because the provenance of these letters is unclear, this collection has a certain air of mystery about it. Kolb’s bibliographic citations do not provide clues, and the records at Brandeis are a bit murky regarding their acquisition, although a 1966 Brandeis University Bulletin announces the acquisition of the letters and quotes Milton Hindus, the Peter and Elizabeth Wolkenstein Professor of English, on their scholarly value. Readers interested in details about the publication process of In Search of Lost Time as it documented in these letters and its role in shaping the ultimate form of Proust's novel can turn to Proust’s Deadline by Christine Cano. The historical, social and literary context that she provides is a useful guide to the people and events mentioned in these letters, and it fleshes out Proust's thoughts about the effects of the editing process on the overall structure and message of his book.

Because the provenance of these letters is unclear, this collection has a certain air of mystery about it. Kolb’s bibliographic citations do not provide clues, and the records at Brandeis are a bit murky regarding their acquisition, although a 1966 Brandeis University Bulletin announces the acquisition of the letters and quotes Milton Hindus, the Peter and Elizabeth Wolkenstein Professor of English, on their scholarly value. Readers interested in details about the publication process of In Search of Lost Time as it documented in these letters and its role in shaping the ultimate form of Proust's novel can turn to Proust’s Deadline by Christine Cano. The historical, social and literary context that she provides is a useful guide to the people and events mentioned in these letters, and it fleshes out Proust's thoughts about the effects of the editing process on the overall structure and message of his book.

For both scholars and general readers of In Search of Lost Time, physical contact with this correspondence serves to join turn-of-the-century Paris to the present. Poring over Proust’s notoriously difficult handwriting, examining the stationery that he himself touched, and sensing the rhythms of his thoughts are interpretive acts that may rival those necessary for reading Proust’s magnum opus. The tactile reality of these letters fosters at once an emotional intimacy and an intellectual bond between the reader and this French writer who died in 1922.

For both scholars and general readers of In Search of Lost Time, physical contact with this correspondence serves to join turn-of-the-century Paris to the present. Poring over Proust’s notoriously difficult handwriting, examining the stationery that he himself touched, and sensing the rhythms of his thoughts are interpretive acts that may rival those necessary for reading Proust’s magnum opus. The tactile reality of these letters fosters at once an emotional intimacy and an intellectual bond between the reader and this French writer who died in 1922.

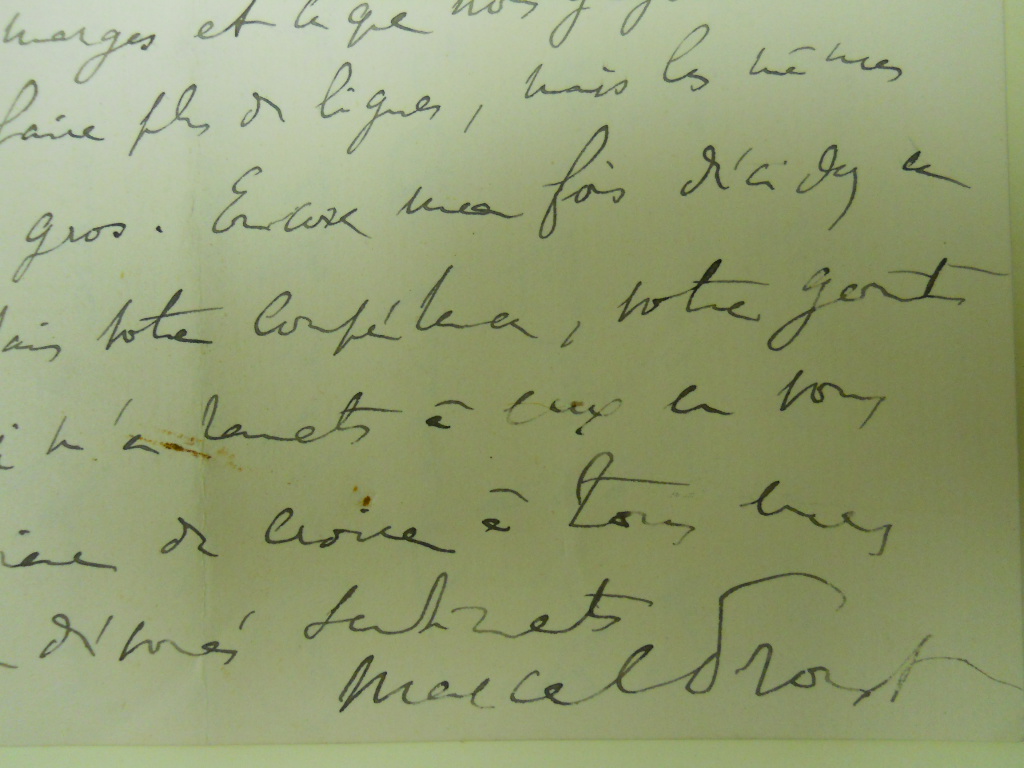

The challenge of dealing with Proust’s manuscripts, above and beyond his infamously poor handwriting, are well known to students of his work, and many of his peculiar graphic habits show up in his letters. Like his manuscripts that devolve into a maze of paragraphs sprouting in divergent directions on a single page, Proust’s letters tend to unfurl in unusual ways. Typically, on a horizontal sheet of stationery folded into halves, the right-hand side is covered with words flowing from top to bottom; page two continues in the same manner on a separate sheet of paper, also folded into two sections. For page three, Proust turns page two vertically and writes along the fold, continuing to the bottom of the sheet of paper; and page 4 begins at the halfway fold of page one and continues to the bottom of that page. To take full advantage of the writing space he has, Proust often adds notes in the blank areas at the beginning and end of his letters. These meticulous efforts to fill the space available to him anticipate Proust’s suggestions, spelled out in later letters (1.2, for example), for extending into the margin the text of his too-lengthy first volume in an attempt to squeeze his manuscript into the number of pages prescribed by Grasset.

The challenge of dealing with Proust’s manuscripts, above and beyond his infamously poor handwriting, are well known to students of his work, and many of his peculiar graphic habits show up in his letters. Like his manuscripts that devolve into a maze of paragraphs sprouting in divergent directions on a single page, Proust’s letters tend to unfurl in unusual ways. Typically, on a horizontal sheet of stationery folded into halves, the right-hand side is covered with words flowing from top to bottom; page two continues in the same manner on a separate sheet of paper, also folded into two sections. For page three, Proust turns page two vertically and writes along the fold, continuing to the bottom of the sheet of paper; and page 4 begins at the halfway fold of page one and continues to the bottom of that page. To take full advantage of the writing space he has, Proust often adds notes in the blank areas at the beginning and end of his letters. These meticulous efforts to fill the space available to him anticipate Proust’s suggestions, spelled out in later letters (1.2, for example), for extending into the margin the text of his too-lengthy first volume in an attempt to squeeze his manuscript into the number of pages prescribed by Grasset.

One of the most moving aspects of these letters is their representation in metaphorical terms of the substantial obstacles that Proust had to overcome in order to publish Swann and the rest of his novel. As Proust’s thoughts unfold on paper and his sinuous sentences deplete the ink in his fountain pen, the fading words are a physical reminder of his struggles against poor health, dwindling financial reserves, and, of course, the passage of time. When, after a stretch of fading text, suddenly dark, bold words reappear, reinforced and strengthened from a fresh dip of the pen, the reader senses that Proust, having taken a deep breath, is ready to continue observing, assessing, reflecting, and, above all, writing.

One of the most moving aspects of these letters is their representation in metaphorical terms of the substantial obstacles that Proust had to overcome in order to publish Swann and the rest of his novel. As Proust’s thoughts unfold on paper and his sinuous sentences deplete the ink in his fountain pen, the fading words are a physical reminder of his struggles against poor health, dwindling financial reserves, and, of course, the passage of time. When, after a stretch of fading text, suddenly dark, bold words reappear, reinforced and strengthened from a fresh dip of the pen, the reader senses that Proust, having taken a deep breath, is ready to continue observing, assessing, reflecting, and, above all, writing.

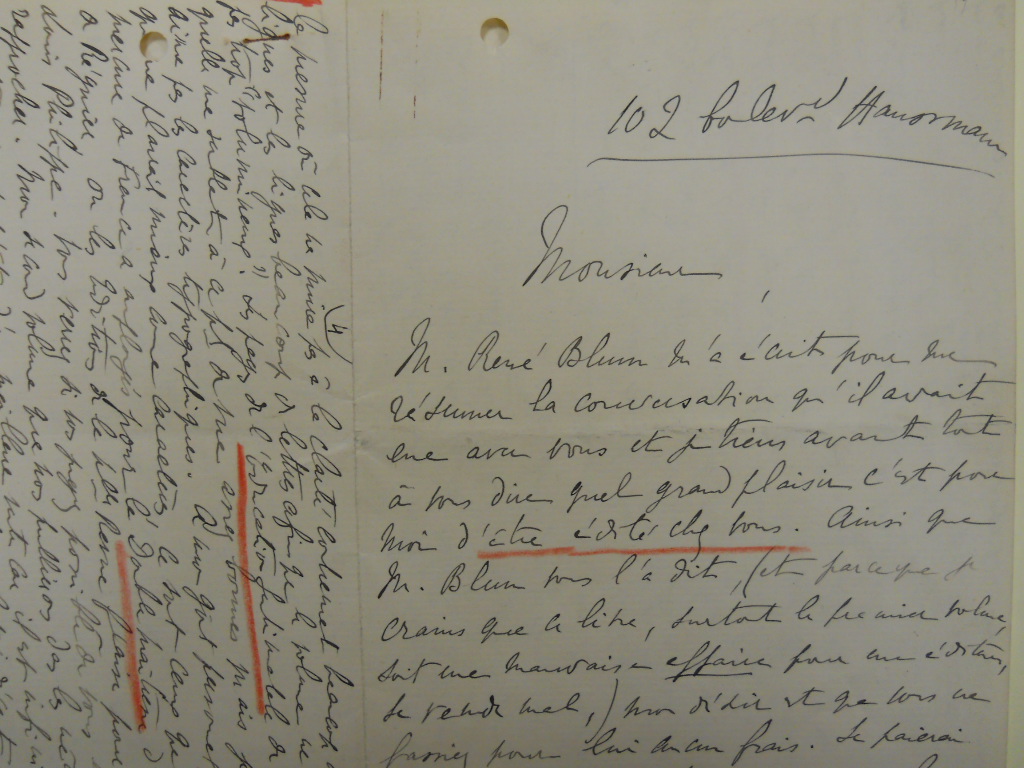

A closer look at the earliest letter (1.7) in the Brandeis collection gives a good idea of the dense layers of information for which many of these pages of correspondence can be mined. In this initial letter, written on February 24, 1913, Proust has clearly concluded a deal that makes Grasset the publisher of what will eventually become Du côté de chez Swann. By this time, Proust had already met with rejection from five other editors, so it is not surprising that he seems thrilled finally to be working with Grasset. The author expresses concerns about the editing and publication process, especially the negative effect that they may have on the format of his novel. Particularly worrisome to him is the problem posed by its excessive length, more than 700 pages. Determined to squeeze more words into the limited number of pages of the first volume, Proust suggests a smaller font size. (Nevertheless, despite his efforts in future letters to invent more ways to reduce the book's heft, Swann eventually will appear in bookstores with no fewer than 523 pages [Cano 49].)

A closer look at the earliest letter (1.7) in the Brandeis collection gives a good idea of the dense layers of information for which many of these pages of correspondence can be mined. In this initial letter, written on February 24, 1913, Proust has clearly concluded a deal that makes Grasset the publisher of what will eventually become Du côté de chez Swann. By this time, Proust had already met with rejection from five other editors, so it is not surprising that he seems thrilled finally to be working with Grasset. The author expresses concerns about the editing and publication process, especially the negative effect that they may have on the format of his novel. Particularly worrisome to him is the problem posed by its excessive length, more than 700 pages. Determined to squeeze more words into the limited number of pages of the first volume, Proust suggests a smaller font size. (Nevertheless, despite his efforts in future letters to invent more ways to reduce the book's heft, Swann eventually will appear in bookstores with no fewer than 523 pages [Cano 49].)

In order to avoid becoming a financial drain (“une mauvaise affaire”) on Grasset and to retain some control over the eventual configuration of his book, Proust states his clear intention to pay the full cost of advertising and publishing the novel (“tous les frais de l’édition ainsi que la publicité"). Above all, the author wishes to preserve the intrinsic coherence of his work, whether or not it is immediately obvious to his readers. He is confident that the second volume—at this point, there are only two on the immediate horizon--will sell more easily ("fera peut'être une meilleure vente") because it is a more traditional narrative and contains a scandalous scene ("il est infiniment plus narratif et peut'être aussi car il est fort indécent"), but he hopes that its element of licentiousness does not prove to be the only reason for its financial success ("mais je regretterai que ce fut là la cause de son succès").

Similar efforts to safeguard the structure and format of his book emerge in this same letter during Proust's discussion with Grasset about the title of his novel. At this point, the author has given his work the provisional title Lost Time (1st part) and Lost Time (2nd part) [Le Temps Perdu (1ère partie) et l'autre Le Temps Perdu (2e partie)], which he justifies "because in truth it is a single work" ("[p]uisque en réalité c'est un seul ouvrage").

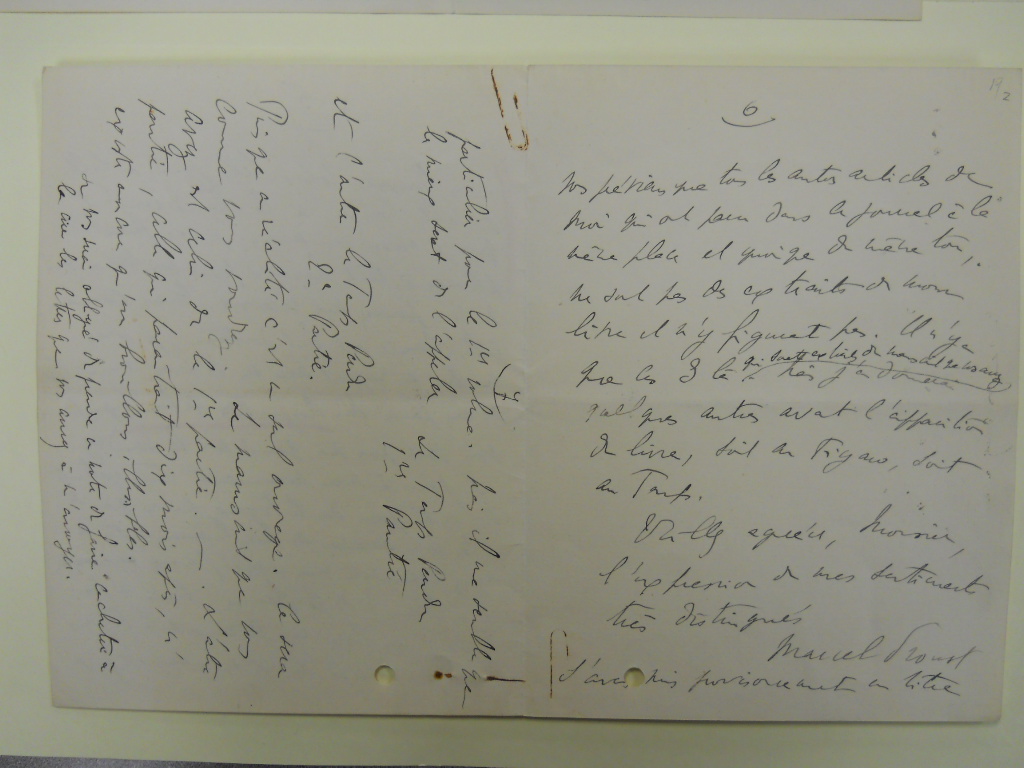

Proust mentions three excerpts from his manuscript, "Épines blanches, épines roses"; "Rayon de soleil sur le balcon"; and "L’Église de village," that had previously appeared in Le Figaro, and he suggests that Grasset read them in order to get "an idea (rather inexact at that) of the configuration" (“une idée [assez inexacte d’ailleurs] de la forme”) of the book that he will be publishing. Between March and September 1912, Le Figaro had published these short texts ("prépublications") from the first volume in order to build readers' interest in the novel. Proust tells Grasset that he plans to furnish more excerpts to Le Figaro or to another newspaper, Le Temps, before the appearance of the book in bookstores. At the end of this letter in a post scriptum, Proust indicates his hope that Swann can be published in May 1913, although he admits that this might not be possible. As an alternative, he proposes the beginning of October 1913 for the first volume and June 1914 for the second.

Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way) is finally published in November of 1913, but world events delay the balance of Proust’s plans. By August 1914, Europe is engulfed in war, Grasset has been drafted, and the publication of Proust’s novel is suspended indefinitely. The second volume of In Search of Lost Time eventually finds its way into print in 1918, published by Gallimard's Nouvelle Revue Française instead of Éditions Grasset, which Proust leaves in 1916. The letters in the rest of this collection offer readers insights into the artistic differences and pragmatic disagreements that will lead to the rupture. This invaluable collection of letters enables the reader to retrace key moments in the publication history of In Search of Lost Time, to relive Proust's anxieties about and aspirations for his book, and to gain a new level of understanding about how the production process ultimately shaped the first volume of this groundbreaking French novel.

I want to express my heartfelt thanks to Archives and Special Collections Director Sarah Shoemaker, Professor Stephen Whitfield (AMST), and Professor Martine Voiret (ROMS) for alerting me to these letters and helping me explore their contents.

Works Cited

Cano, Christine. Proust’s Deadline. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Kolb, Phillip, ed. Correspondance de Marcel Proust. Paris: Plon, 1970.

-----. Marcel Proust: Selected Letters. Trans. Terence Kilmartin. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992.

Proust, Marcel. A la recherche du temps perdu. Paris: Gallimard, 1987-89.

-----. In Search of Lost Time. Trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff, Terence Kilmartin, and D.J. Enright. New York: Modern Library, 2003.