Revolutionary Books and Revolutionary Wars

November 4, 2013

Description by Craig Bruce Smith, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in History.

The revolutions of the late 17th through the early 19th centuries were a time of great political upheaval. These revolutions were wars born from ideas. As such, words more than bullets or blades became the chief revolutionary weapons. Despite the geographical diversity of these conflicts, scattered across North America, Europe, the Caribbean, and South America, beliefs in natural rights, freedom and liberty were their foundation. While thoughts gave way to actions, the roots and evolution of these changes can be transparently viewed through the words crafted by the participants. And numerous examples of the Age of Revolutions’ ideas can be found in the print and manuscript sources housed in the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections. Brandeis’ collections analyze the question of what theoretically and tangibly separates rebellion from revolution, and revolution from civil war.

The revolutions of the late 17th through the early 19th centuries were a time of great political upheaval. These revolutions were wars born from ideas. As such, words more than bullets or blades became the chief revolutionary weapons. Despite the geographical diversity of these conflicts, scattered across North America, Europe, the Caribbean, and South America, beliefs in natural rights, freedom and liberty were their foundation. While thoughts gave way to actions, the roots and evolution of these changes can be transparently viewed through the words crafted by the participants. And numerous examples of the Age of Revolutions’ ideas can be found in the print and manuscript sources housed in the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections. Brandeis’ collections analyze the question of what theoretically and tangibly separates rebellion from revolution, and revolution from civil war.

Drawn from many different collections, most prominently from the Charles J. Tanenbaum Collection, Brandeis’ revolutionary holdings comprise an array of rare books (many first editions), pamphlets, engravings and manuscript documents that chronicle, among others, the Glorious, American, French, Haitian, and Latin American revolutions. Brandeis’ sources allow researchers to follow the ideological spread of the spirit of the revolution throughout the Atlantic World. What emerges is a transnational stream of thought, which manifests itself in diverse ways, forcing its actors and the reader to question the rules and limits of revolution.

Drawn from many different collections, most prominently from the Charles J. Tanenbaum Collection, Brandeis’ revolutionary holdings comprise an array of rare books (many first editions), pamphlets, engravings and manuscript documents that chronicle, among others, the Glorious, American, French, Haitian, and Latin American revolutions. Brandeis’ sources allow researchers to follow the ideological spread of the spirit of the revolution throughout the Atlantic World. What emerges is a transnational stream of thought, which manifests itself in diverse ways, forcing its actors and the reader to question the rules and limits of revolution.

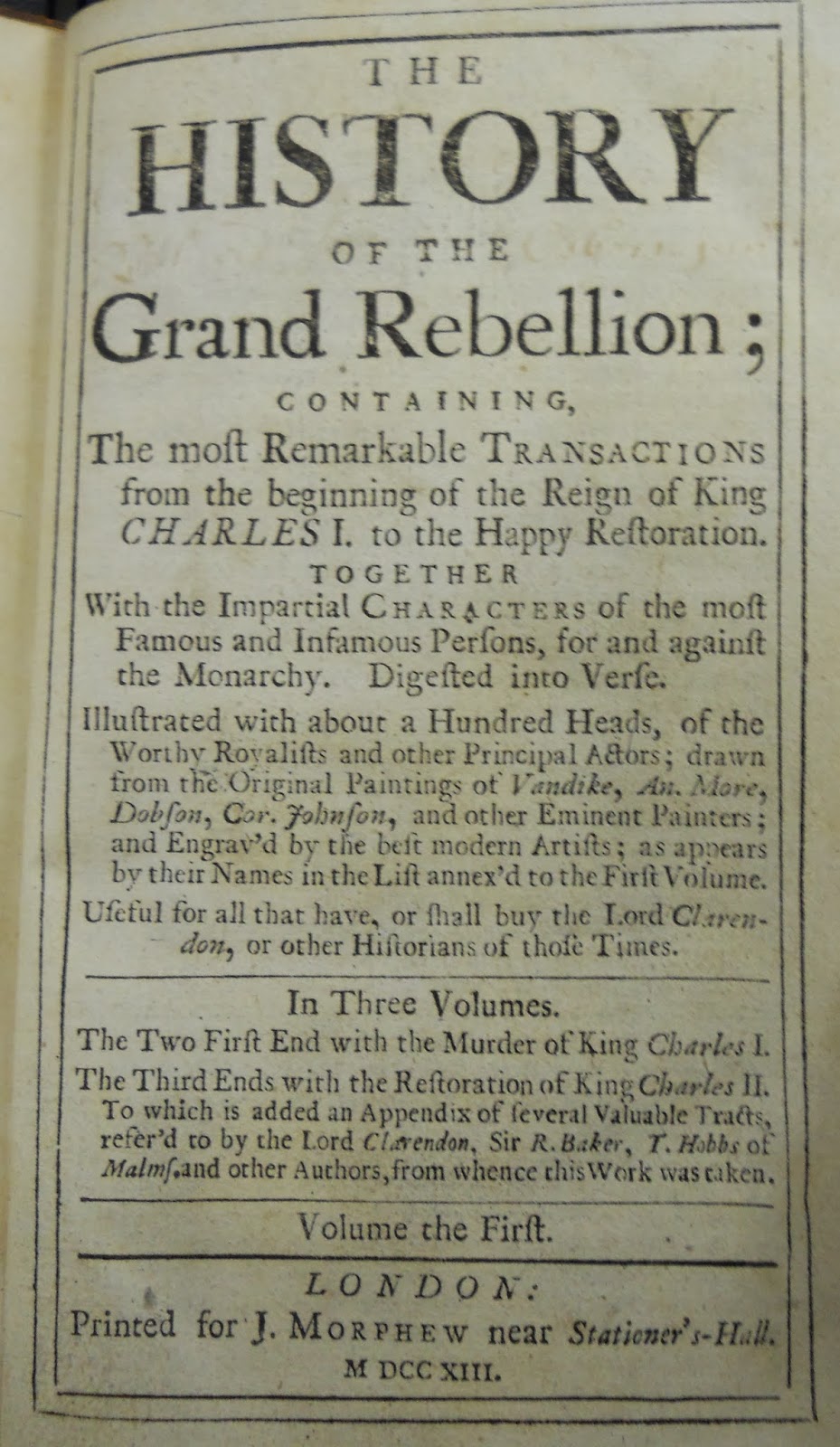

Primarily comprised of English sources, but also supplemented by those in French, Brandeis’ volumes follow the arch of revolutionary conceptions of liberty across three centuries and continents. The earliest of these texts, published in 1642 during the English Civil War, is A Declaration of the Lords and Commons Assembled in Parliament. It establishes a motif common in the early days of the revolutionary culture—from 18th century America to 20th century Russia: the good king (in this case Charles II), blinded by his evil advisors and misled by the queen (foreshadowing the ominous specters of Queen Marie Antoinette of France and Czarina Alexandra of Russia). But six years later, The Charge of the Commons of England Against Charl[e]s Stuart, King of England would detail another revolutionary first: the trial and execution of a nation’s sovereign by his own subjects. However, 1723’s anonymously authored The History of England would chronicle what the writer considered the error of this choice, as it ignores virtually the entire rule of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, and makes a drastic and unsubtle leap from Charles I to Charles II. In similar fashion, Edward Ward’s The History of the Grand Rebellion (1713) regards Cromwell as a rebel and speaks of the return of the monarchy as a “happy restoration” [1]. Revolution must be principled. Revolutionary ideals varied greatly based on varying versions of thoughts and ethics.

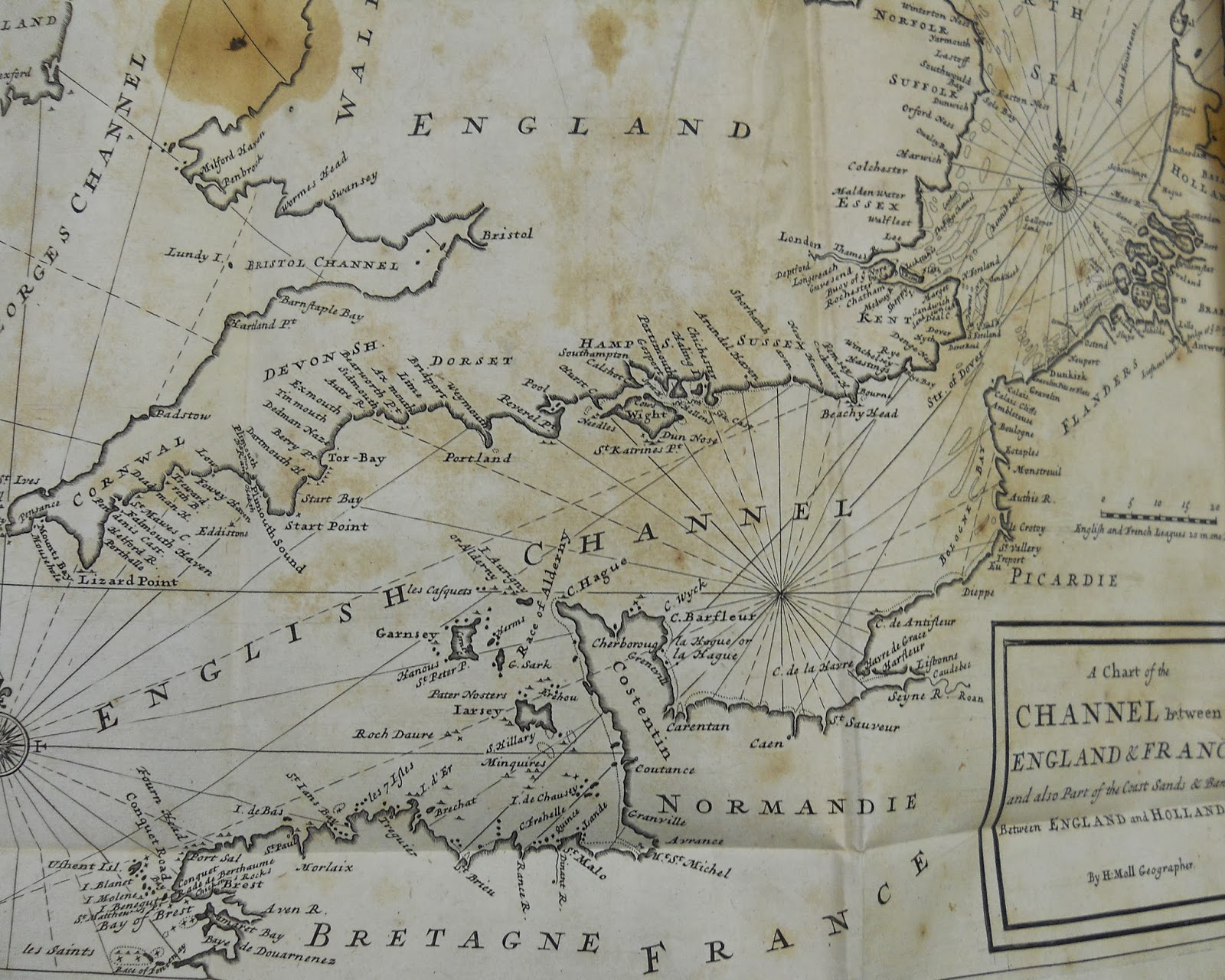

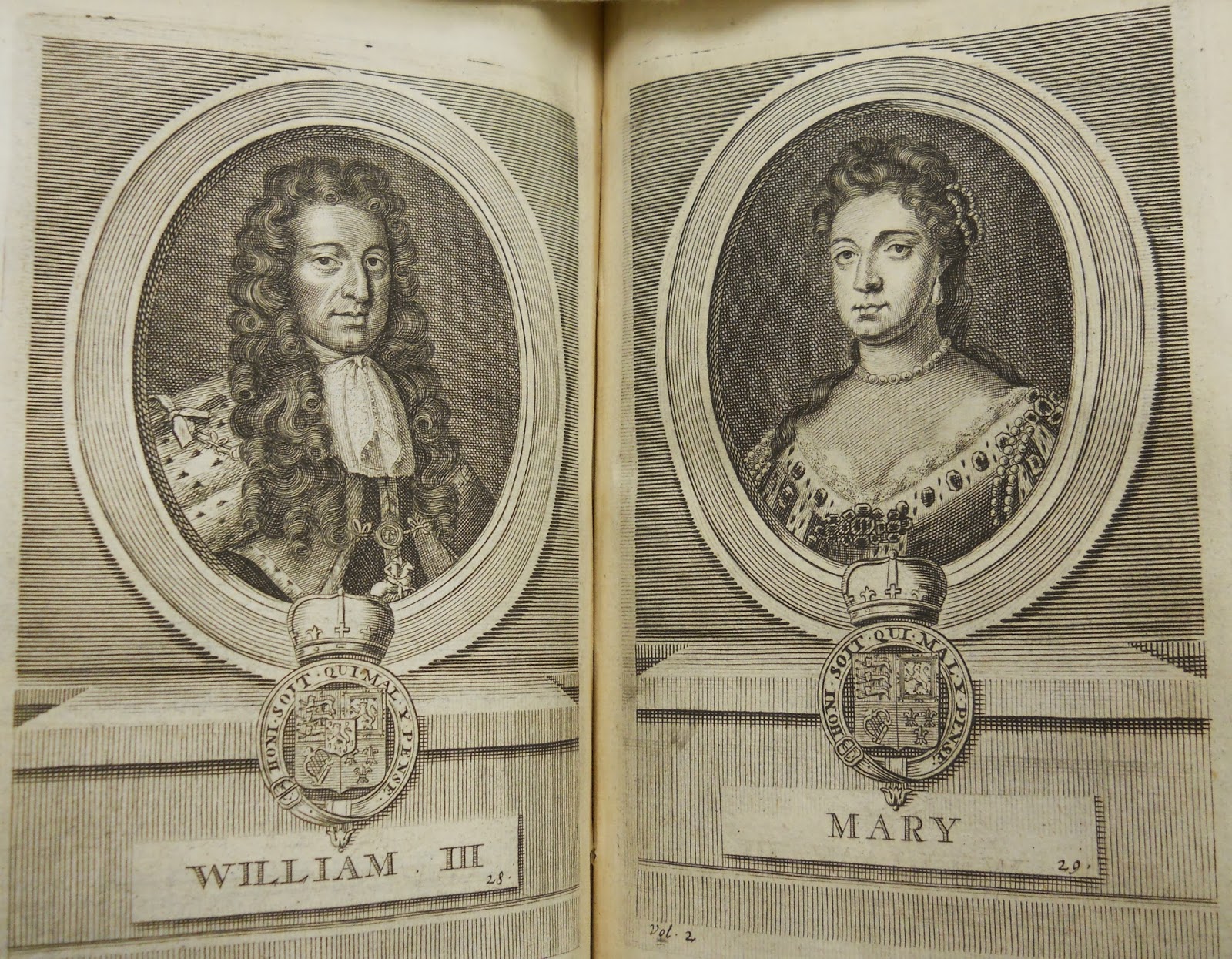

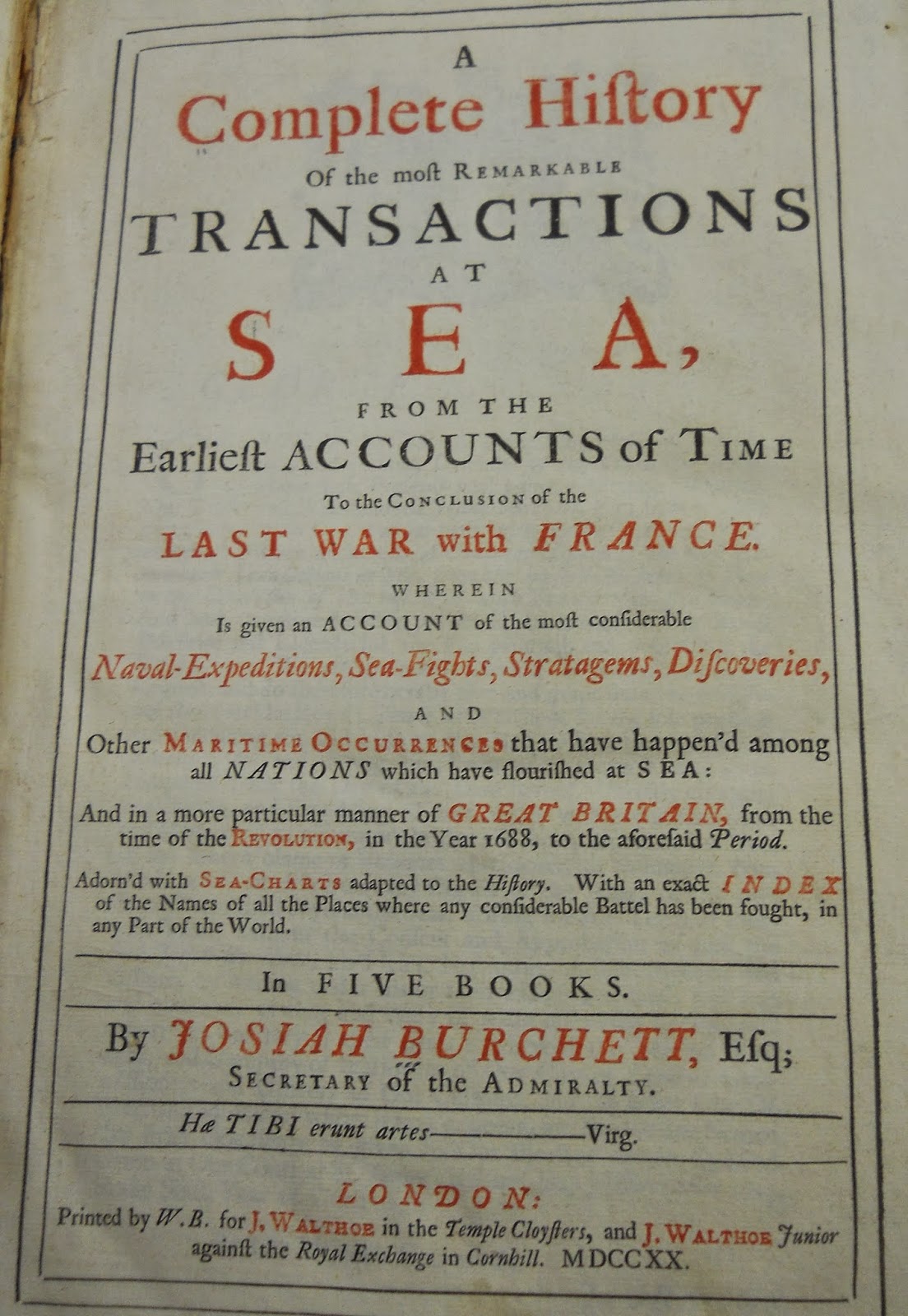

A denigration of one governmental change was not indicative of an opposition to revolutions in principle. Typical of this, the aforementioned book, the History of England, is not inherently dismissive of the spirit of revolution, only of its less desirable manifestations—the English Civil War went too far, whereas the 1688 Glorious Revolution receives a discussion worthy of its name. The author seeks to give his readers the “true History” of the event, which naturally details the British people casting off “deplorable Circumstances… under the Yoke of Papistick [sic] Tyranny… and the Loss of their Civil Privileges and Properties.” In dethroning King James II, England was embracing its Lockean “natural Right[s]” and Dutch Prince William of Orange and English Princess Mary were heralded as virtuous deliverers [2]. As the revolution lacked a great deal of the bloodshed so common in other such conflicts, it was glorified. But efforts were still made to heroicize and martialize this relatively peaceful revolution. Nearly three decades after the event, secretary of the admiralty Josiah Burchett continued to present King William’s mostly uneventful sea voyage from Holland with all the grandeur of an epic battle in A Complete History of the most Remarkable Transactions at Sea (1720).

A denigration of one governmental change was not indicative of an opposition to revolutions in principle. Typical of this, the aforementioned book, the History of England, is not inherently dismissive of the spirit of revolution, only of its less desirable manifestations—the English Civil War went too far, whereas the 1688 Glorious Revolution receives a discussion worthy of its name. The author seeks to give his readers the “true History” of the event, which naturally details the British people casting off “deplorable Circumstances… under the Yoke of Papistick [sic] Tyranny… and the Loss of their Civil Privileges and Properties.” In dethroning King James II, England was embracing its Lockean “natural Right[s]” and Dutch Prince William of Orange and English Princess Mary were heralded as virtuous deliverers [2]. As the revolution lacked a great deal of the bloodshed so common in other such conflicts, it was glorified. But efforts were still made to heroicize and martialize this relatively peaceful revolution. Nearly three decades after the event, secretary of the admiralty Josiah Burchett continued to present King William’s mostly uneventful sea voyage from Holland with all the grandeur of an epic battle in A Complete History of the most Remarkable Transactions at Sea (1720).

The accounts of the history of 1688 helped spread the intellectual tradition of the Glorious Revolution, which in turn inspired a tenacious desire amongst Englishmen, on both sides of the Atlantic, to protect their natural rights. But what exactly were they? This question would become central to the growing turmoil in the American colonies during the 1760s and 1770s, and, despite any formalized government bill documenting them, Englishmen could turn to 1757’s A Guide to the Knowledge of the Rights and Privileges of Englishmen. Drawing on the traditional sources of English rights dating back to the Magna Carta, this book advanced the government’s obligation to have “secured every Man in the quiet Possession of his Rights, Liberties, and Properties.” These were “antient [sic] Rights and Privileges” that were acquired at birth [3]. Such texts would have only bolstered the American colonists’ resolve to defend themselves against what they viewed as Parliamentary tyranny.

The accounts of the history of 1688 helped spread the intellectual tradition of the Glorious Revolution, which in turn inspired a tenacious desire amongst Englishmen, on both sides of the Atlantic, to protect their natural rights. But what exactly were they? This question would become central to the growing turmoil in the American colonies during the 1760s and 1770s, and, despite any formalized government bill documenting them, Englishmen could turn to 1757’s A Guide to the Knowledge of the Rights and Privileges of Englishmen. Drawing on the traditional sources of English rights dating back to the Magna Carta, this book advanced the government’s obligation to have “secured every Man in the quiet Possession of his Rights, Liberties, and Properties.” These were “antient [sic] Rights and Privileges” that were acquired at birth [3]. Such texts would have only bolstered the American colonists’ resolve to defend themselves against what they viewed as Parliamentary tyranny.

Brandeis’ books on the American Revolutionary era are particularly interesting not only because they consist of some of the most well-known texts of the period, but also because they contain many London-published versions. Such volumes possess an inherent and intriguing dichotomy that places the American colonial views in debate with those in Britain. The prefaces and editor’s introductions are a veritable treasure trove of political and ideological discourse on the principles of rights and liberty.

Brandeis’ books on the American Revolutionary era are particularly interesting not only because they consist of some of the most well-known texts of the period, but also because they contain many London-published versions. Such volumes possess an inherent and intriguing dichotomy that places the American colonial views in debate with those in Britain. The prefaces and editor’s introductions are a veritable treasure trove of political and ideological discourse on the principles of rights and liberty.

Naturally, many British views are not complimentary towards the American cause. Speaking for the sentiments of Parliament in general, Soame Jenyns’s The Objections to the Taxation of our American Colonies (1765) was shocked by the American claims, writing “The Right of the Legislature of Great Britain to impose Taxes on her American Colonies… are Propositions so indisputably clear, that I should never have thought it necessary to have undertaken their Defence.” According to Jenyns, the colonists were intellectually ignorant of the true meaning of “Liberty, Property, [and] Englishmen.” Instead, he claimed, the colonists were bandying about such terms in order to “make strong Impressions on that more numerous Part of Mankind, who have Ears but not Understanding [4].”

Naturally, many British views are not complimentary towards the American cause. Speaking for the sentiments of Parliament in general, Soame Jenyns’s The Objections to the Taxation of our American Colonies (1765) was shocked by the American claims, writing “The Right of the Legislature of Great Britain to impose Taxes on her American Colonies… are Propositions so indisputably clear, that I should never have thought it necessary to have undertaken their Defence.” According to Jenyns, the colonists were intellectually ignorant of the true meaning of “Liberty, Property, [and] Englishmen.” Instead, he claimed, the colonists were bandying about such terms in order to “make strong Impressions on that more numerous Part of Mankind, who have Ears but not Understanding [4].”

Taking further issue with how American thinking led to action, The Report of the Lords Committees, Appointed by the House of Lords to Enquire into the Several Proceedings in the Colony of Massachusett's [sic] Bay(1774) placed the blame for the discord firmly on the colonists. Showing a less than stellar regard for objectivity, the Boston Massacre (which is misdated as occurring in 1768, rather than the actual 1770) was presented as a display of the British soldiers' discipline and “utmost Endeavours to prevent Mischief” framed against the colonial mob and the use by “Rioters” of physical “Blows, and every Act of Aggravation” [5]. It shows a conscious British effort to challenge the very principles and ethics of American resistance. Likewise, the combined London printing of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776), which called for American independence, along with its antithesis Plain Sense, which claimed the “Scheme of Independence is ruinous, delusive and impracticable,” symbolizes this inherent clash over thoughts through words.

Taking further issue with how American thinking led to action, The Report of the Lords Committees, Appointed by the House of Lords to Enquire into the Several Proceedings in the Colony of Massachusett's [sic] Bay(1774) placed the blame for the discord firmly on the colonists. Showing a less than stellar regard for objectivity, the Boston Massacre (which is misdated as occurring in 1768, rather than the actual 1770) was presented as a display of the British soldiers' discipline and “utmost Endeavours to prevent Mischief” framed against the colonial mob and the use by “Rioters” of physical “Blows, and every Act of Aggravation” [5]. It shows a conscious British effort to challenge the very principles and ethics of American resistance. Likewise, the combined London printing of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776), which called for American independence, along with its antithesis Plain Sense, which claimed the “Scheme of Independence is ruinous, delusive and impracticable,” symbolizes this inherent clash over thoughts through words.

Despite the common perception of British opposition, English voices of understanding and conciliation often emerged. In Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1768), American patriot John Dickinson lamented that British “taxation therefore is the mode suited to arbitrary and oppressive governments'; meanwhile, in the preface of this work, Dickinson’s London editor tried to calm the more incendiary British subjects, warning his countrymen to “never be so angry with her colonies as to strike them.” British politician and former Massachusetts governor Thomas Pownall’s The Administration of the British Colonies (1766 and 1774) prophesied that “either an American or British union” had to be formed—“There is no other alternative,” and urged Parliament that “The truly great and wise man will not judge of the people from their passions” [6]. The Speech of Edmund Burke (1775) urged reconciliation and presented Americans as the heirs of the Glorious revolution’s tradition, as British MP Edmund Burke detailed “This fierce spirit of the Liberty is stronger in the English Colonies probably than in any other people of the earth” [7].

Despite the common perception of British opposition, English voices of understanding and conciliation often emerged. In Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1768), American patriot John Dickinson lamented that British “taxation therefore is the mode suited to arbitrary and oppressive governments'; meanwhile, in the preface of this work, Dickinson’s London editor tried to calm the more incendiary British subjects, warning his countrymen to “never be so angry with her colonies as to strike them.” British politician and former Massachusetts governor Thomas Pownall’s The Administration of the British Colonies (1766 and 1774) prophesied that “either an American or British union” had to be formed—“There is no other alternative,” and urged Parliament that “The truly great and wise man will not judge of the people from their passions” [6]. The Speech of Edmund Burke (1775) urged reconciliation and presented Americans as the heirs of the Glorious revolution’s tradition, as British MP Edmund Burke detailed “This fierce spirit of the Liberty is stronger in the English Colonies probably than in any other people of the earth” [7].

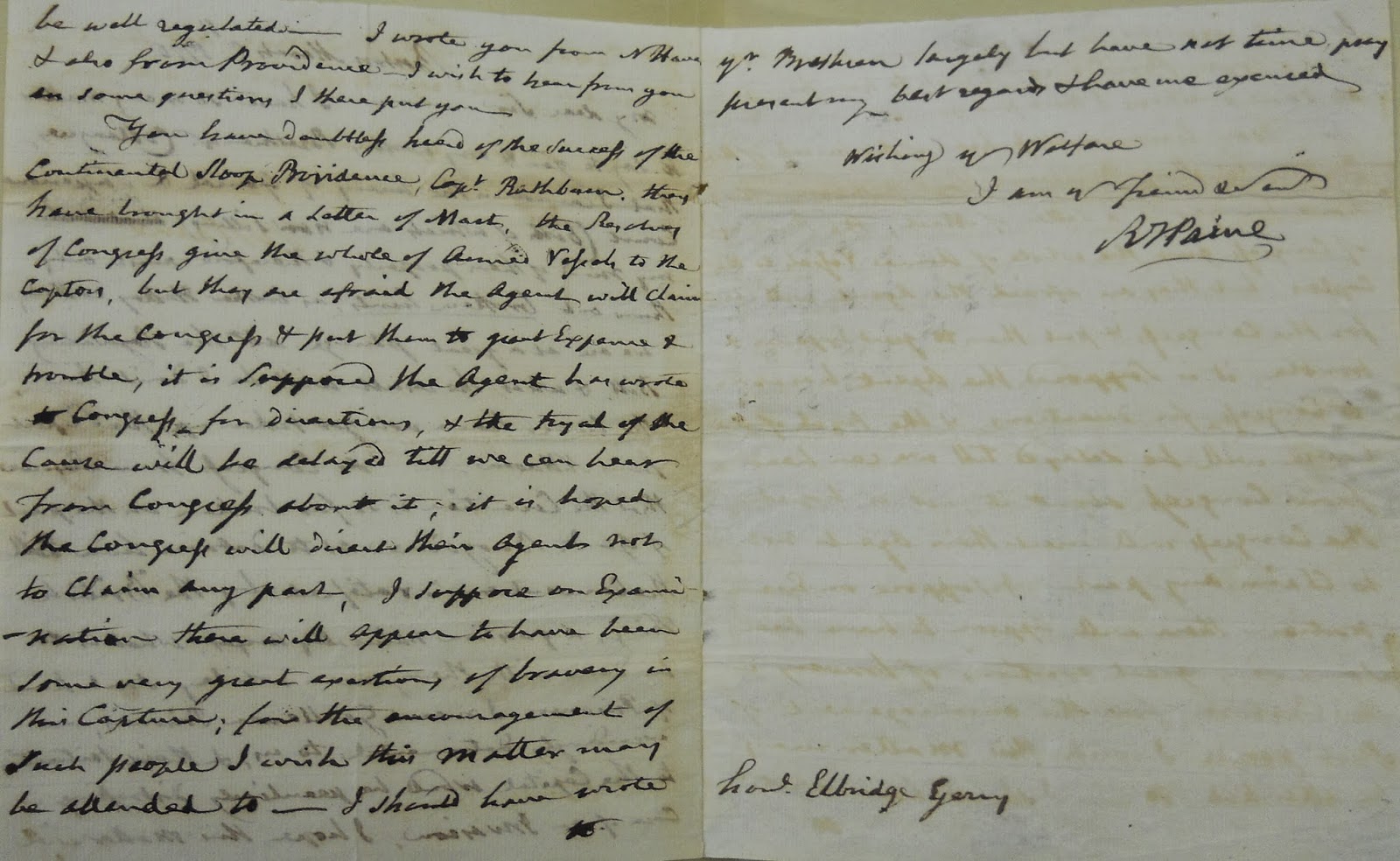

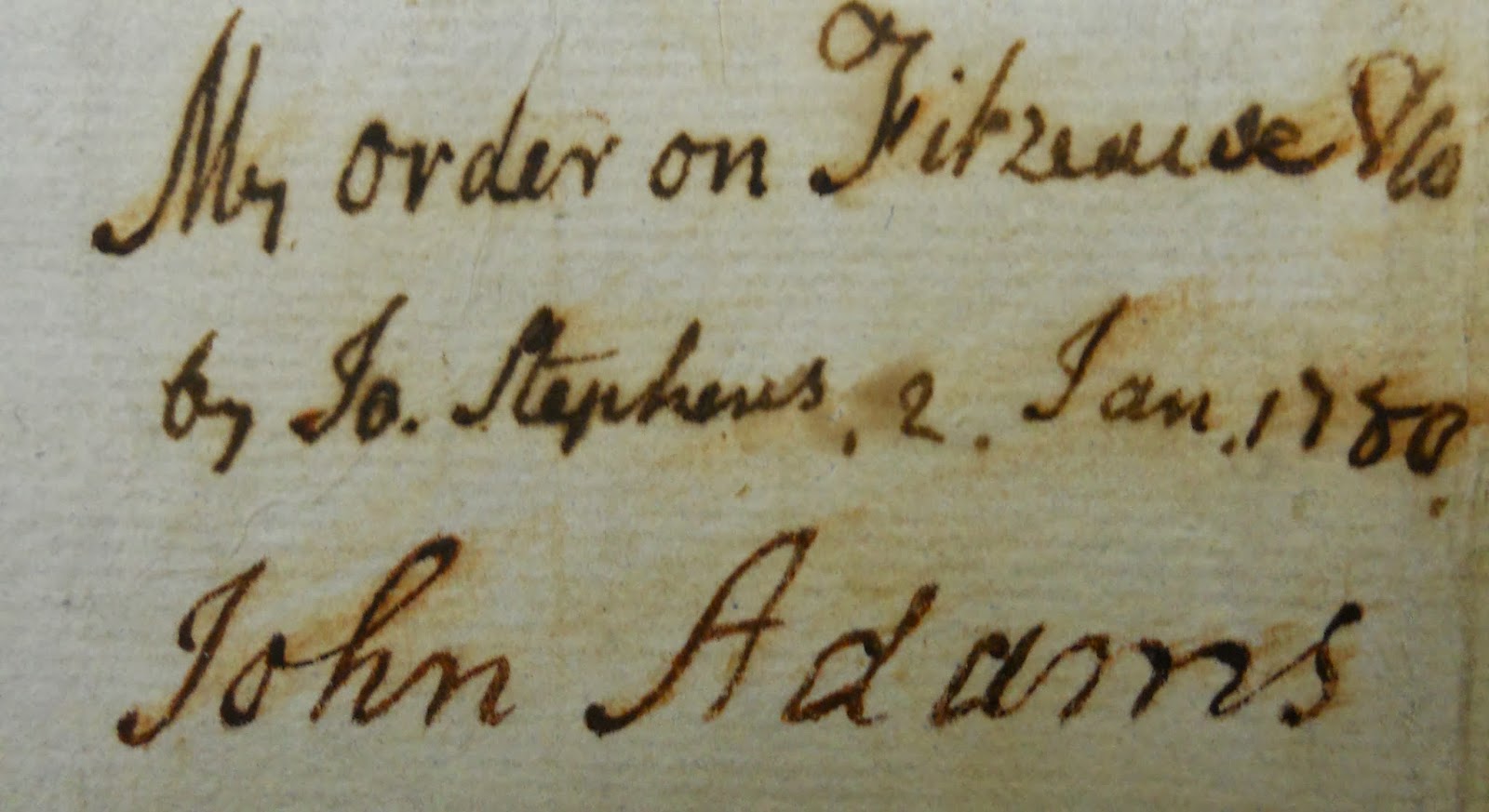

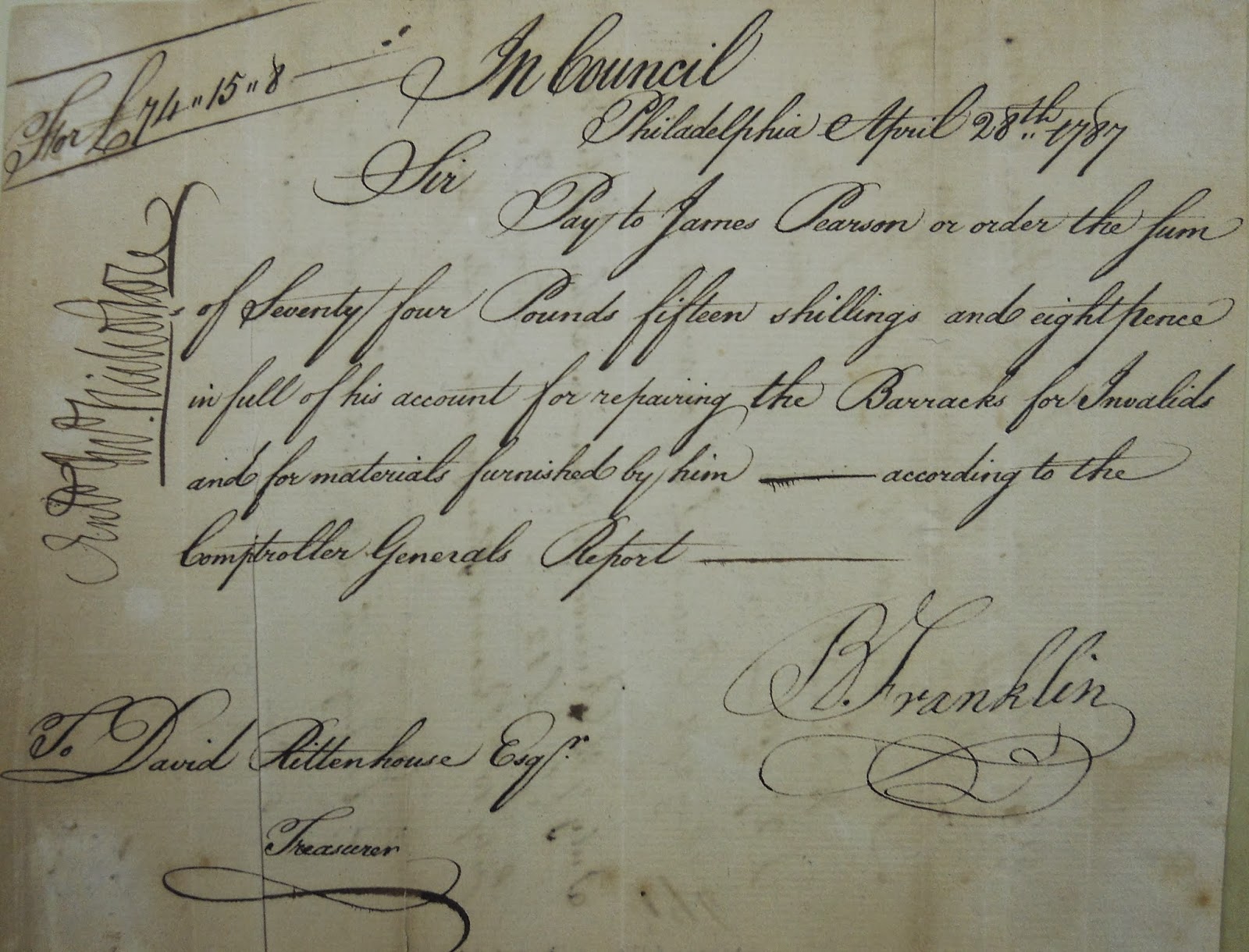

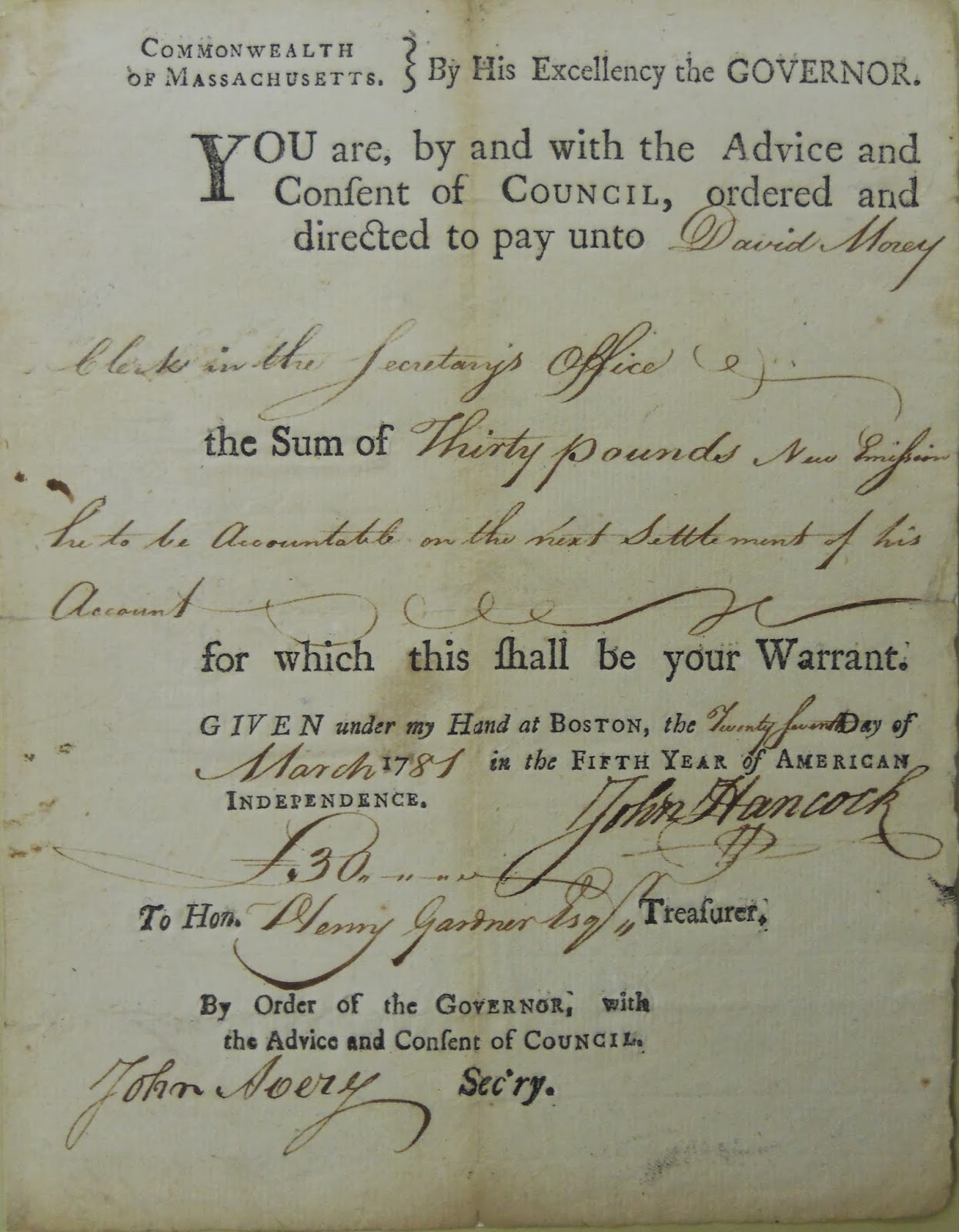

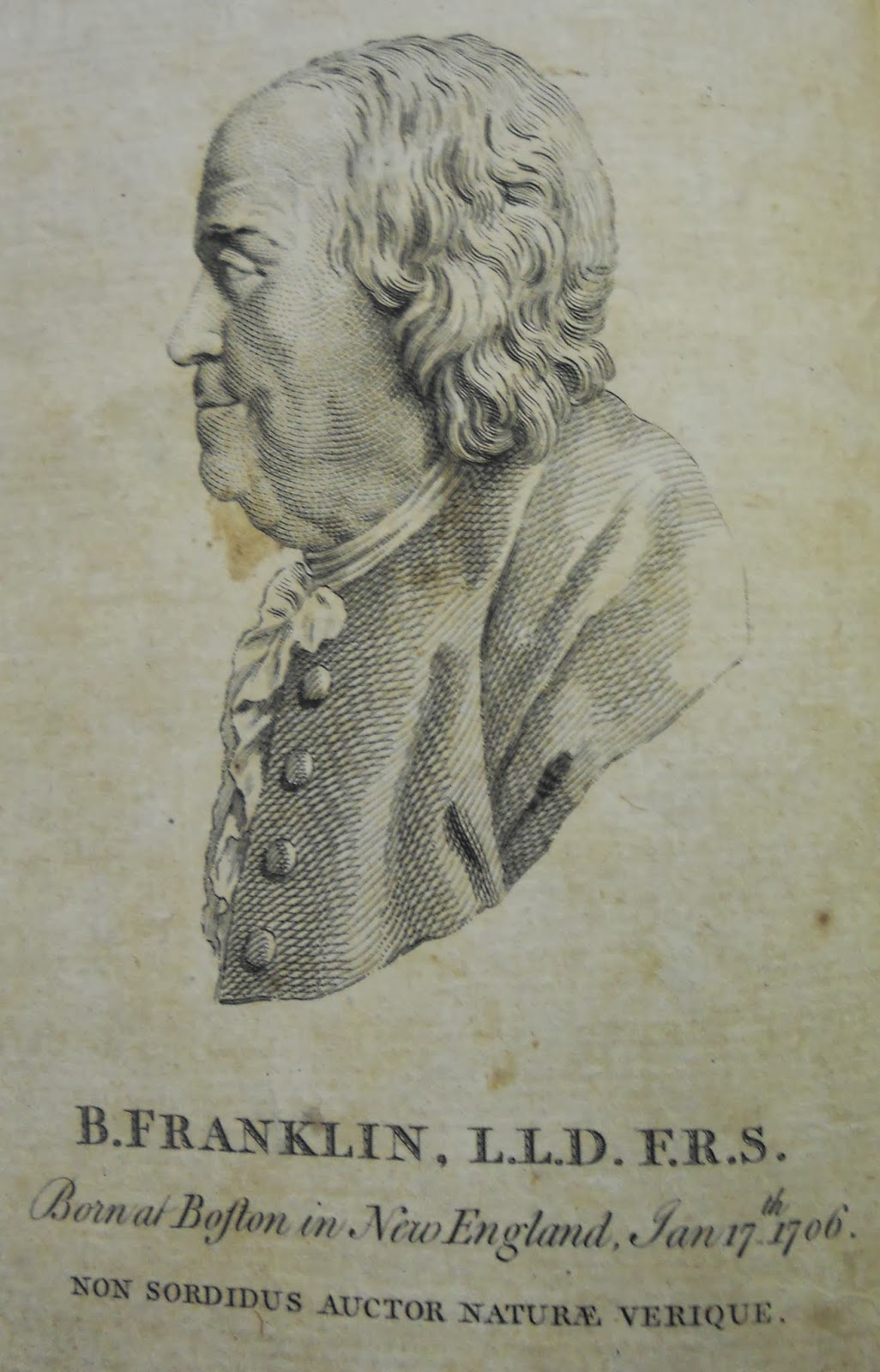

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections is also home to many writings from key American founders, including printed volumes, manuscript letters and documents penned by people such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Franklin is especially well represented, with a 1779 edition of his collected writings, entitled Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces, which contains his personal musings on the coming of the American Revolution. Likewise, a signed presentation copy of John Adams’ A Defence of the Constitution of Government of the United States of America (1788) offers resounding support for the new American republic (complete with an early printing of the U.S. Constitution), while also remembering its ideological roots. As Adams reminds his readers, the American Revolutions’ origins lie across the Atlantic in Britain, “The English nation, for their improvements in the theory of government, has, at least, more merit with the human race than any other among the moderns… Americans too ought forever to acknowledge their obligations to English writers” [8]. Words and books, regardless of their national origins, could bring about revolutionary change.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections is also home to many writings from key American founders, including printed volumes, manuscript letters and documents penned by people such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Franklin is especially well represented, with a 1779 edition of his collected writings, entitled Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces, which contains his personal musings on the coming of the American Revolution. Likewise, a signed presentation copy of John Adams’ A Defence of the Constitution of Government of the United States of America (1788) offers resounding support for the new American republic (complete with an early printing of the U.S. Constitution), while also remembering its ideological roots. As Adams reminds his readers, the American Revolutions’ origins lie across the Atlantic in Britain, “The English nation, for their improvements in the theory of government, has, at least, more merit with the human race than any other among the moderns… Americans too ought forever to acknowledge their obligations to English writers” [8]. Words and books, regardless of their national origins, could bring about revolutionary change.

Also available through Brandeis are biographies on central figures, ranging from Charles Caldwell’s Memoirs of the Life and Campaigns of the Hon. Nathaniel Greene (1819), William Wirt’s Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (1818), and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall’s five-volume The Life of George Washington (1804), which humorously doesn’t even mention its titular figure until page 377. But one of the brightest gems of Brandeis’ collections is a first edition copy of Franklin’s famed Autobiography, which was originally published in Paris in 1791 under the name Memoires de la Vie Privée de Benjamin Franklin. This work would come to have an immense impact not only on America, but also on another nation galvanized by the spreading spirit of revolution: France.

Also available through Brandeis are biographies on central figures, ranging from Charles Caldwell’s Memoirs of the Life and Campaigns of the Hon. Nathaniel Greene (1819), William Wirt’s Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (1818), and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall’s five-volume The Life of George Washington (1804), which humorously doesn’t even mention its titular figure until page 377. But one of the brightest gems of Brandeis’ collections is a first edition copy of Franklin’s famed Autobiography, which was originally published in Paris in 1791 under the name Memoires de la Vie Privée de Benjamin Franklin. This work would come to have an immense impact not only on America, but also on another nation galvanized by the spreading spirit of revolution: France.

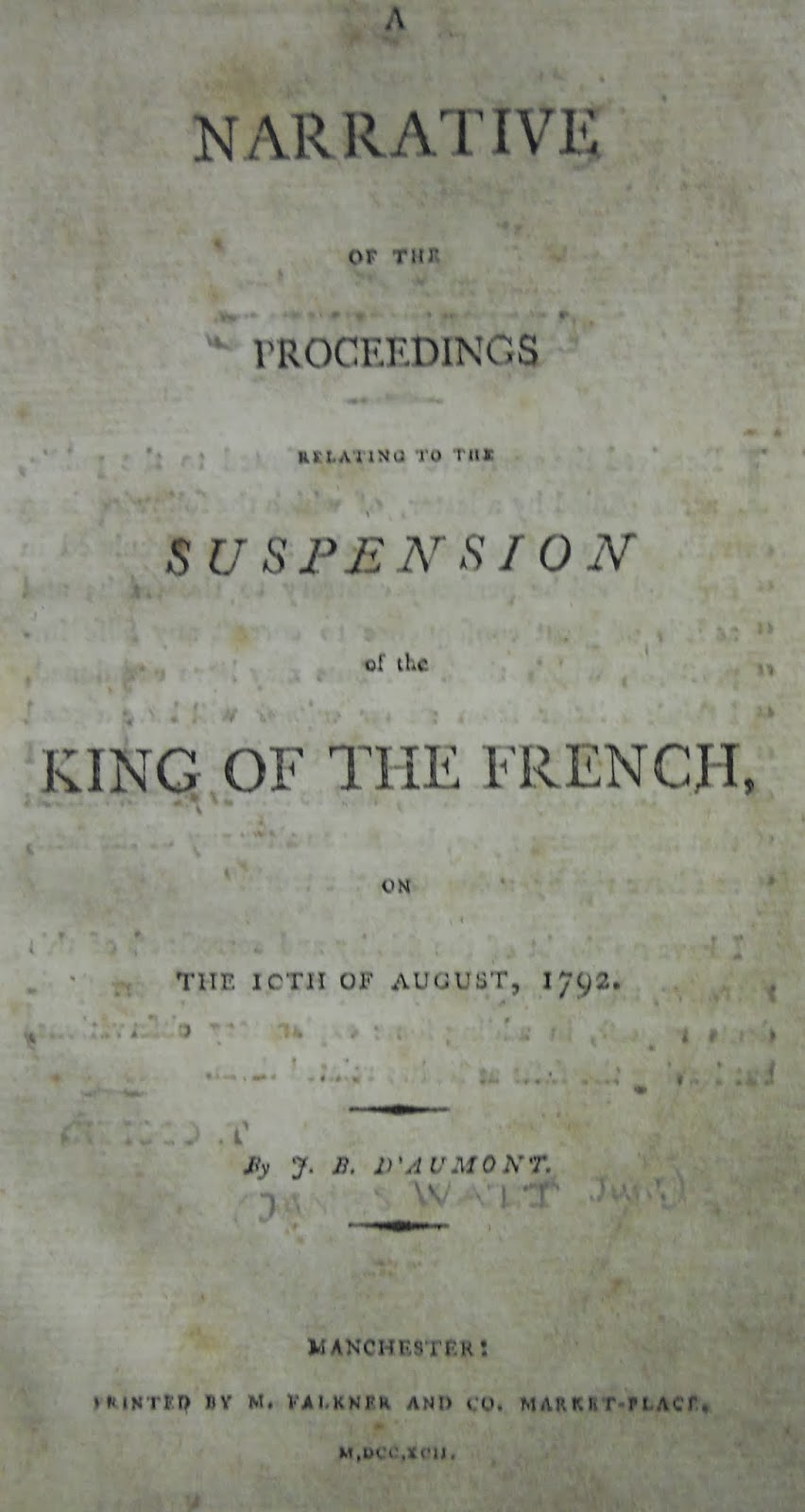

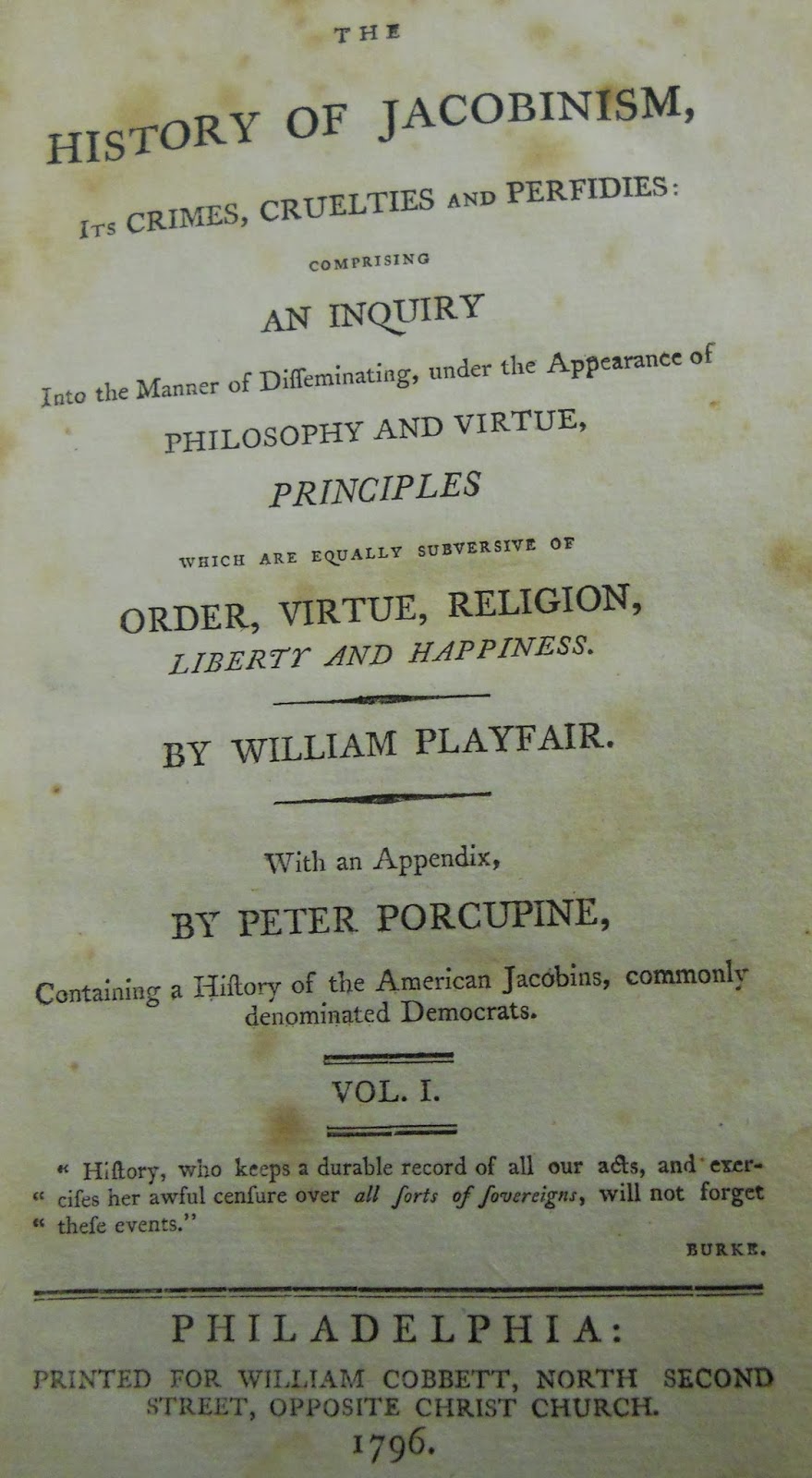

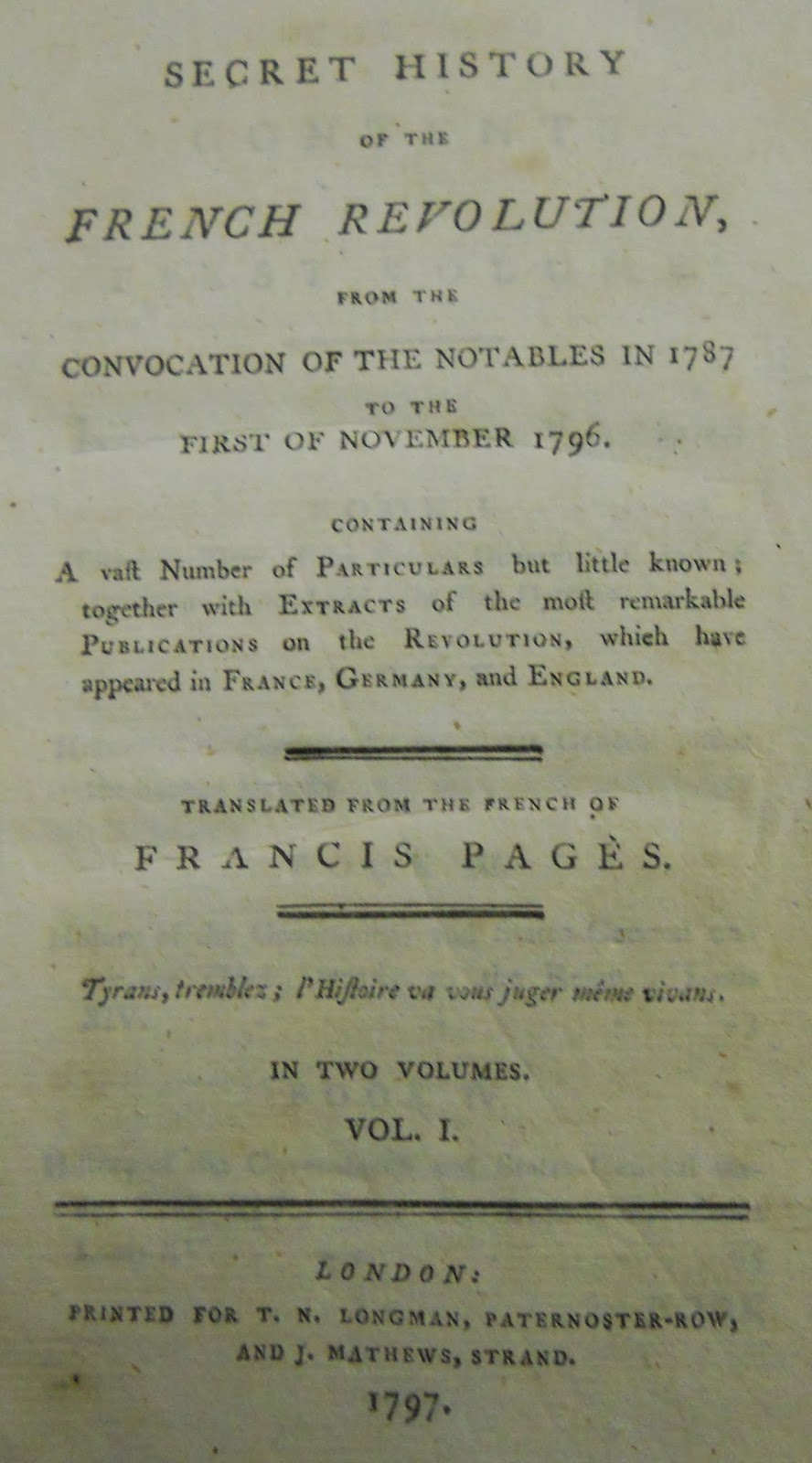

While Brandeis houses an extensive collection of French-language pamphlets and books on the French Revolution, its English-language texts (published in both Britain and America) are the most striking, as they present a critique of a revolution gone wrong though excessive violence and immorality. Like The History of England and Edward Ward's The History of the Grand Rebellion’s celebration of the “happy restoration” of the monarchy, the French execution of King Louis XVI is portrayed as a deterioration of revolutionary ideals and virtue. In The History of Jacobinsim, Its Crimes, Cruelties and Perfidies (1796), William Playfair, a Scot who actually stormed the Bastille, regards the French Revolution as possessing “First motives of the insurrection [that were] good, but soon became bad.” Displaying obvious personal disillusionment, his explicit subtitle, Comprising An Inquiry Into the Manner of Disseminating, under the Appearance of Philosophy and Virtue, Principles which are Equally subversive of Order, Virtue, Religion, Liberty, and Happiness, suggests the Jacobins’ ideology was grounded in “the cruelty and want of any attention to principle… proofs that violent revolutions destroy the moral principle in man.” Supposedly lacking a moral foundation, the French Republic was a warning, a country where its new government, “the national assembly[,] leads the people astray.” The same volume’s appendix, written by the pseudonymous Peter Porcupine (English author William Cobbett, also the work’s publisher), warned Americans that a similar fate could befall their own nation from those “who thence took the name Anti-federalists… in general, bad men of bad moral characters, embarrassed in their private affairs, or the tools of such as were” [9].

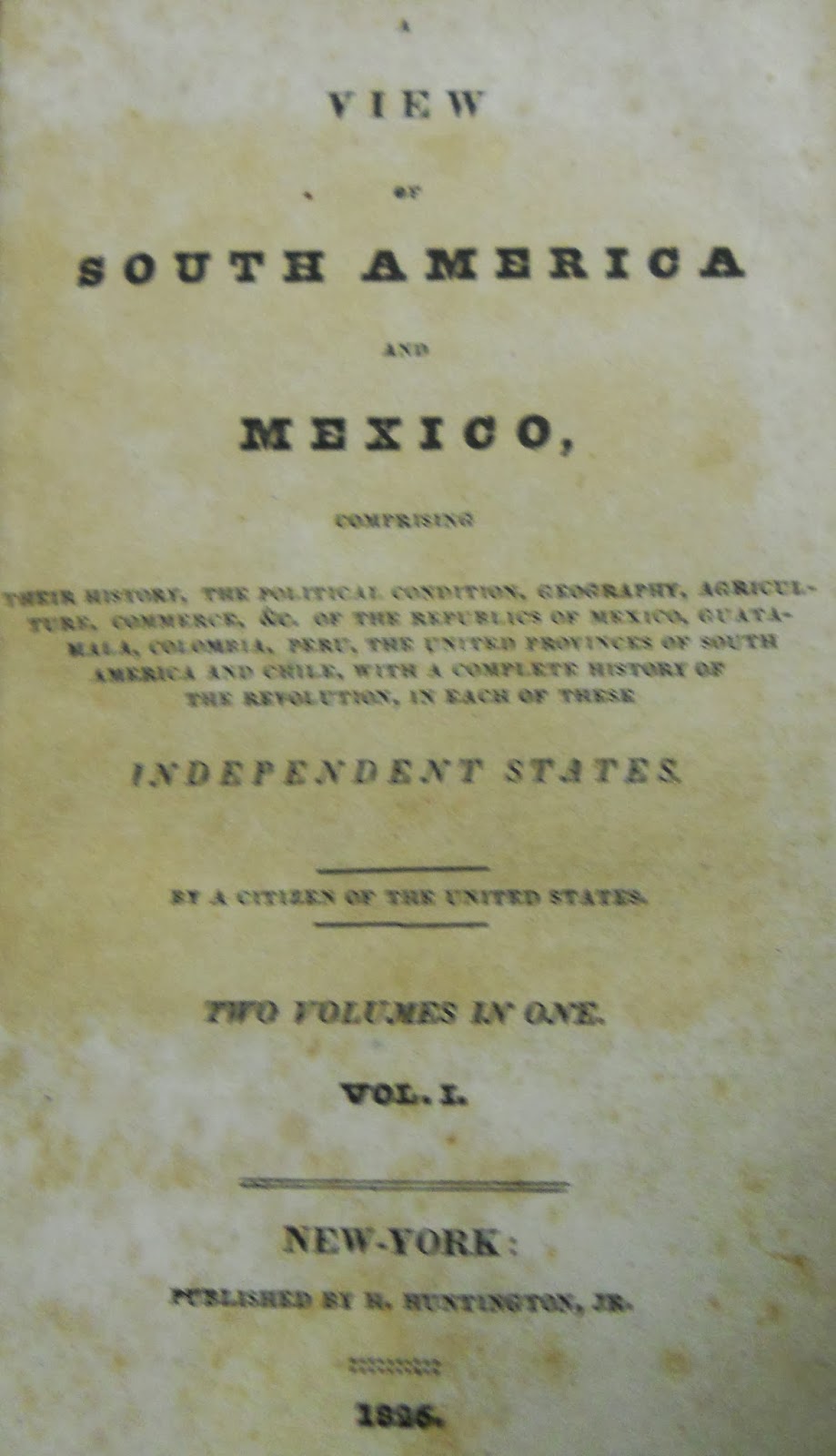

With a similar negative appraisal in An Historical Survey of the French Colony in the Island of St. Domingo (1797), British politician and slavery proponent Bryan Edwards dismisses the Haitian Revolution as a collection of “horrors of which imagination cannot adequately conceive nor pen describe.” With obvious bias, the slaves of the island of St. Domingo (later Haiti) revolting for freedom were portrayed as “savage people, habituated to the barbarities of Africa,” who did not fight properly but “avail themselves of the silence and obscurity of the night, and fall on the peaceful and unsuspicious planters… the old and the young, the matron, the virgin, and the helpless infant”[10]. In stark contrast to Edwards, A View of South America and Mexico… A Complete History of the Revolution in each of these Independent States (1826), authored by the U.S. Minister to Spain, Alexander Hill Everett, characterized the Latin American independence movement of the 19th century as “a revolution which has terminated so gloriously,” likely because of its similarities to the American Revolution [11]. There was a clear ideological divide centered on the ethics and beliefs behind each revolution. Victory was not enough to justify its ideals; the means were on trial before the early modern world.

With a similar negative appraisal in An Historical Survey of the French Colony in the Island of St. Domingo (1797), British politician and slavery proponent Bryan Edwards dismisses the Haitian Revolution as a collection of “horrors of which imagination cannot adequately conceive nor pen describe.” With obvious bias, the slaves of the island of St. Domingo (later Haiti) revolting for freedom were portrayed as “savage people, habituated to the barbarities of Africa,” who did not fight properly but “avail themselves of the silence and obscurity of the night, and fall on the peaceful and unsuspicious planters… the old and the young, the matron, the virgin, and the helpless infant”[10]. In stark contrast to Edwards, A View of South America and Mexico… A Complete History of the Revolution in each of these Independent States (1826), authored by the U.S. Minister to Spain, Alexander Hill Everett, characterized the Latin American independence movement of the 19th century as “a revolution which has terminated so gloriously,” likely because of its similarities to the American Revolution [11]. There was a clear ideological divide centered on the ethics and beliefs behind each revolution. Victory was not enough to justify its ideals; the means were on trial before the early modern world.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections' revolutionary books present a variety of understanding on liberty and revolution from a wide array of cultural perspectives. These holdings are particularly useful, as they offer nuances and diverse representations of revolutionary ideology. Through these books, a reader can find that while the spirit of revolution may have spread, the manner in which each war was fought became its principle means of judgment and justification.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections' revolutionary books present a variety of understanding on liberty and revolution from a wide array of cultural perspectives. These holdings are particularly useful, as they offer nuances and diverse representations of revolutionary ideology. Through these books, a reader can find that while the spirit of revolution may have spread, the manner in which each war was fought became its principle means of judgment and justification.

Notes

- Edward Ward. The History of the Grand Rebellion… to the Happy Restoration… London: J. Morphew, 1713.

- The History of England: Faithfully Extracted from Authentick [sic] Records, Approved Manuscripts, an the most Celebrated Histoies of this Kingdom…Vol. II. , p. 125.

A Guide to the Knowledge of the Rights and Privileges of Englishmen. Containing, I. Magna Carta…II. The Bishop’s Curses…III the Habeas Corpus Act…IV The Bill of Rights…V. The act of Settlement…London: J. Scott, MDCCLVII [1757], p. iii-iv.

A Guide to the Knowledge of the Rights and Privileges of Englishmen. Containing, I. Magna Carta…II. The Bishop’s Curses…III the Habeas Corpus Act…IV The Bill of Rights…V. The act of Settlement…London: J. Scott, MDCCLVII [1757], p. iii-iv.- Soame Jenyns. The Objections to the Taxation of our American Colonies, By the Legislature of Great Britain Briefly Consider’d. London: J. Wilkie, 1765, p. 3-4.

- The Report of the Lords Committees, Appointed by the House of Lords to Enquire into the Several Proceedings in the Colony of Massachusett’s Bay, in Opposition to the Sovereignty of His Majesty, in His Parliament of Great Britain, over that Province; and also what hath passed in this House relative thereto, from the Frist Day of January, 1764. London: Charles Eyre and William Strahan, MDCCLXXIV, p. 12.

Thomas Pownall. The Administration of the British Colonies. Vol. I. London: J. Walter, 1774, p. xiv; The Administration of the Colonies. 3rd edition. London: J. Dodsley and J. Walter, 1766.

Thomas Pownall. The Administration of the British Colonies. Vol. I. London: J. Walter, 1774, p. xiv; The Administration of the Colonies. 3rd edition. London: J. Dodsley and J. Walter, 1766.- The Speech of Edmund Burke, Esq; On Moving His Resolutions for Conciliation with the Colonies, March 22, 1775. London: J. Dodsley, 1775, p. 16.

- John Adams. A Defence of the Constitution of Government of the United States of America. Vol. III. London: C. Dilly, 1788, p. 209.

- William Playfair. The History of Jacobinism, Its Crimes, Cruelties and Perfidies: Comprising An Inquiry Into the Manner of Disseminating, under the Appearance of Philosophy and Virtue, Principles which are Equally subversive of Order, Virtue, Religion, Liberty, and Happiness…With an Appendix, By Peter Porcupine Containing a History of the American Jacobins, commonly denominated Democrats. Philadelphia: William Cobbett, 1796, p. I: 127, 173; II: 8.

- Bryan Edwards. An Historical Survey of the French Colony in the Island of St. Domingo…London: John Stockdale, 1797, p. 63-64.

- Alexander Hill Everett. A View of South America and Mexico…A Complete History of the Revolution in each of these Independent States. Vol. I. New York: H. Huntington Jr., 1826, p. iii.