Samuel Gridley Howe Library Collection

August 26, 2011

Description by Aaron Wirth, PhD candidate in history

Brandeis University’s Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department houses a wide array of material from the Walter E. Fernald Developmental Center’s Samuel Gridley Howe Library. This collection includes several hundred books from scholars and experts in the fields of science, medicine and disabilities; the papers of Irving Kenneth Zola and of Rosemary and Gunnar Dybwad; and thousands of pamphlets, case studies and journals on topics ranging from what were then called feeblemindedness and cretinism to eugenics and crime. The material, which dates from the 1810s to the 1950s and is related primarily to North America and the United Kingdom, was compiled by the Howe Library from the school superintendent’s library as well as international libraries. It includes works from world-renowned doctors such as psychologists Alfred Binet and Edgar A. Doll, polymaths Francis Galton and his protégé Karl Pearson, Walter E. Fernald, Dorothea Dix (who championed for the rights of the indigent insane), Ellis Island medical officer Howard Knox and eugenicists Charles B. Davenport and Henry H. Goddard, among hundreds of others. The Samuel G. Howe Library Collection’s academic scope is vast and will be of interest to historians of science and medicine, anthropologists, sociologists and people with disabilities and their families.

Brandeis University’s Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department houses a wide array of material from the Walter E. Fernald Developmental Center’s Samuel Gridley Howe Library. This collection includes several hundred books from scholars and experts in the fields of science, medicine and disabilities; the papers of Irving Kenneth Zola and of Rosemary and Gunnar Dybwad; and thousands of pamphlets, case studies and journals on topics ranging from what were then called feeblemindedness and cretinism to eugenics and crime. The material, which dates from the 1810s to the 1950s and is related primarily to North America and the United Kingdom, was compiled by the Howe Library from the school superintendent’s library as well as international libraries. It includes works from world-renowned doctors such as psychologists Alfred Binet and Edgar A. Doll, polymaths Francis Galton and his protégé Karl Pearson, Walter E. Fernald, Dorothea Dix (who championed for the rights of the indigent insane), Ellis Island medical officer Howard Knox and eugenicists Charles B. Davenport and Henry H. Goddard, among hundreds of others. The Samuel G. Howe Library Collection’s academic scope is vast and will be of interest to historians of science and medicine, anthropologists, sociologists and people with disabilities and their families.

Founded in South Boston in 1850 (with the help of an appropriation from Massachusetts two years earlier) by physician and abolitionist Samuel Gridley Howe and medical activist Dorothea Dix, the Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feebleminded Youth, eventually known as the Walter E. Fernald State School, became the United States’ first institution and oldest publicly-funded thanks to an appropriation from the Massachusetts Legislature, for so-called “feebleminded” boys and girls (the term included all types or grades of mental, moral and physical disabilities characterizing various groups, from the profound “idiot” up to individuals who possessed attributes but little below the normal standard of human intelligence). By the late 1860s, Dr. Howe’s educational reforms for his mentally disabled patients were quite successful and influenced similar institutions throughout North America. At an 1887 conference, Dr. F.M. Powell described how schools for the feebleminded could best help students who were in desperate need of education and reform and the difficulties categorizing individuals:

Founded in South Boston in 1850 (with the help of an appropriation from Massachusetts two years earlier) by physician and abolitionist Samuel Gridley Howe and medical activist Dorothea Dix, the Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feebleminded Youth, eventually known as the Walter E. Fernald State School, became the United States’ first institution and oldest publicly-funded thanks to an appropriation from the Massachusetts Legislature, for so-called “feebleminded” boys and girls (the term included all types or grades of mental, moral and physical disabilities characterizing various groups, from the profound “idiot” up to individuals who possessed attributes but little below the normal standard of human intelligence). By the late 1860s, Dr. Howe’s educational reforms for his mentally disabled patients were quite successful and influenced similar institutions throughout North America. At an 1887 conference, Dr. F.M. Powell described how schools for the feebleminded could best help students who were in desperate need of education and reform and the difficulties categorizing individuals:

“The range of capacity characterizing the pupils in the educational department may be almost as varied as their number, each possessing an individuality; but, in a school with two hundred or more children, a satisfactory gradation of classes can be made, by leaving a remnant, possessing more than ordinary peculiarities or eccentricities, to be assigned to special classes for instruction through individual methods. In the graded division, class training is restored, more especially in groups made up of pupils nearest the normal standard of intellect, individual methods being more necessary as we approach the lower grades.”[1]

Powell’s argument that “moronic” pupils, while possessing unique “peculiarities,” should be divided into grades, like a typical public primary school, was based on Howe’s school and served as an example of how to serve those most in need of help.

Powell’s argument that “moronic” pupils, while possessing unique “peculiarities,” should be divided into grades, like a typical public primary school, was based on Howe’s school and served as an example of how to serve those most in need of help.

Howe’s method of education provided the residents with the means to earn wages, live freely and return to their respective communities and even live independently.

Yet many citizens believed because these “idiots”—a polite term for those with mental disabilities at the time—did so well that they should remain in the school, permanently incarcerated at one of the dozen similar institutions in the Western Hemisphere. Dr. Howe, the school’s superintendent, vehemently opposed permanent institutionalization, as he believed that once the students learned basic education, they could be rehabilitated back into society as “decent” citizens.

When Howe retired in 1874, Edward Jarvis, an authority on vital statistics, became the school’s second superintendent. As the Commonwealth saw the school rehabilitate the residents with mental subnormalities into high-functioning disabled youths, it was pressured to admit disabled adults, delinquent youths and even children from broken or poor homes.

When Howe retired in 1874, Edward Jarvis, an authority on vital statistics, became the school’s second superintendent. As the Commonwealth saw the school rehabilitate the residents with mental subnormalities into high-functioning disabled youths, it was pressured to admit disabled adults, delinquent youths and even children from broken or poor homes.

In fact, if a poverty-stricken family decided that the best place for one or all of their children was outside the home, the likelihood of them residing at the Walter E. Fernald School—with patients who were deemed schizophrenic, mongoloids, cretins, epileptic and feebleminded—was high.

At the time, poverty was associated with prostitution and idiocy, so lower-class, uneducated women were the first to be deemed unstable and promiscuous. These women were discouraged from bearing children and were often encouraged to use birth control. Alice Weld Tallant’s speech at an American Academy of Medicine conference details a fascinating conclusion regarding delinquent girls who were committed to schools like Fernald by the courts around the turn of the century:

“Delinquent girls are as a class undoubtedly physically defective, and this must have some bearing on their moral condition. I will therefore modify my opinion far enough to state that delinquency, although certainly connected with poor physical condition, is not its direct result. Rather do the two conditions go hand in hand because they are both results of the same factors, lack of care and oversight at home, broken homes, poor food, neglect, child-labor, malnutrition, unsanitary conditions and indecent overcrowding of the homes. In combating these conditions which make for physical degeneracy, we cannot help but strike a blow against moral delinquency.”[2]

Tallant’s argument advanced a popular idea held at the time: the relationship between delinquency and degeneracy, the mental and the physical. Doctors believed that with the right schooling and proper reform they could tackle both problems at the same time.

Tallant’s argument advanced a popular idea held at the time: the relationship between delinquency and degeneracy, the mental and the physical. Doctors believed that with the right schooling and proper reform they could tackle both problems at the same time.

With government pressure to add adults and wayward children, it became clear that the Fernald school needed more space. So in 1887, with a legislative appropriation of $25,000, the school moved to a hilled neighborhood in Waltham, Massachusetts, that would eventually encompass over 190 acres of land between Trapelo Road and Waverly Oaks Road.[3] What started as a school became a self-contained community: shop courses trained children for farm and industry work; daily education was mandatory; shoe repair, rug making, knitting, sewing, weaving and housekeeping classes allowed students to learn a trade; and dancing and athletics classes allowed them to stay fit. All the while the objective was the same: after acquiring basic academic and job skills, residents were expected to graduate to a life beyond the institution.

While the Howe approach to teaching and training the students continued to be effective, medical arguments and public opinion about them began to change around the turn of the century. Additionally, the school’s third superintendent, Walter E. Fernald, a world-renowned expert on mental retardation, did not did not agree with Howe’s rehabilitation program. By the 1910s, Darwin’s theories of natural selection and a revived interest in Mendelian genetics led many scientists to argue that human traits such as intelligence and morality were biologically rooted. Moreover, under Fernald’s guidance the school took a more scientific stance on the mentally disabled, a phenomenon that gained momentum throughout the Western world. Specifically, the doctor adhered to the fast-rising international bio-social movement called eugenics.

While the Howe approach to teaching and training the students continued to be effective, medical arguments and public opinion about them began to change around the turn of the century. Additionally, the school’s third superintendent, Walter E. Fernald, a world-renowned expert on mental retardation, did not did not agree with Howe’s rehabilitation program. By the 1910s, Darwin’s theories of natural selection and a revived interest in Mendelian genetics led many scientists to argue that human traits such as intelligence and morality were biologically rooted. Moreover, under Fernald’s guidance the school took a more scientific stance on the mentally disabled, a phenomenon that gained momentum throughout the Western world. Specifically, the doctor adhered to the fast-rising international bio-social movement called eugenics.

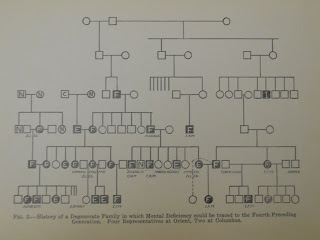

Eugenicists had rediscovered the work of Gregor Mendel. In the mid 1800s, Mendel recorded the results of cross-breeding pea plants and found a very regular statistical pattern for features like height and color. This introduced the concept of genes and research in the field of genetics. One path of genetic research branched off into the study of social theory known as eugenics. It was presented as a mathematical science that could be used to predict the traits and behaviors of humans and to control human breeding, so individuals with the best genes would reproduce, thereby improving the species; this was often done by tracing family histories. At the same time, state officials began to encourage social-service agencies, courts and police to send suspected “morons” for IQ testing based on the Binet-Simon intelligence test; people of color, Jews, southern Europeans, developmentally disabled people, and the rural poor were particularly vulnerable to being labeled as “polluting the gene pool of society.” Those who scored below normal would be admitted to state schools, as they were deemed a danger to the public, and would, as a matter of public policy, be prevented from reproducing. Throughout the process, physicians were viewed by many as their nation’s defenders. It was good for America and it was good for the human race—that was the message. Most of all, the movement saw itself as an optimistic school of thought that relied on the strength of science.

In 1910, C.B. Davenport highlighted eugenic policy with a powerful, thought-provoking proclamation. The doctor declared,

“Governments spend scores of thousands of dollars and establish rigid inspections to prevent the spread of the coitus disease of the horse but the Spirochete parasite that causes corresponding disease in man and entails endless misery on hundreds of thousands of innocent children may be disseminated by any body, and is being disseminated by scores of thousands of persons in this country, unchecked, under the protection of the ‘personal liberty’ flag. Alas! That so little thought is had to the loss of liberty of the infected children. Marriage of persons with venereal disease is not only unfit; it is a hideous and dastardly crime; and its frequency would justify a medical test of all males before marriage, innocent as well as guilty.”[4]

Davenport’s words were meant to upset citizens and motivate them to take action against those who were deemed a menace to society. Another eugenicist, Henry H. Goddard, based the pursuit of the “moron” on fear and mobilization of the masses. In 1916, he declared,

“we need to hunt them out in every possible place and take care of them, and see to it that they do not propagate and make the problem worse, and that those who are alive today do not entail loss of life and property and moral contagion in the community by the things they do because they are weak minded.”[5]

Goddard was not exaggerating in his proclamation to hunt down those who were deemed unfit by society. Several states created so-called traveling clinics that administered IQ tests at public schools around the nation. Many of the clinics labeled children as feebleminded, even though their teachers and parents insisted that they were normal. The clinics separated the children from their families by convincing the parents that an institution offered their children the best possible future. Those families who did not volunteer their children for admission often lost custody of them in court.

Goddard was not exaggerating in his proclamation to hunt down those who were deemed unfit by society. Several states created so-called traveling clinics that administered IQ tests at public schools around the nation. Many of the clinics labeled children as feebleminded, even though their teachers and parents insisted that they were normal. The clinics separated the children from their families by convincing the parents that an institution offered their children the best possible future. Those families who did not volunteer their children for admission often lost custody of them in court.

After Fernald’s death, in 1924, his mission of scientific investigation and the inclusion of poor, delinquent, orphaned and epileptic people in the institution continued under the next superintendent, Dr. Ransom Greene. It is worth noting, however, that this period in science and medicine was not filled entirely with specialties that history deems quackery and pseudoscience. Indeed, major positive breakthroughs occurred in fields such as war neurosis, endocrinology and rights for the handicapped.

During and after World War I (1914-1918), soldiers who suffered from war neurosis, or shellshock, constituted a subgroup of veterans. Their situation illustrated the wider difficulties of World War I returnees. Whether disabled or fully fit, each veteran faced a cluster of problems related to the psychological and social readjustment to civilian society. Moreover, war neurosis forced physicians to conclude that otherwise normal people would break down under sufficient stress. Thus it brought into question previous ideas of degeneration, which implied that there was a split between the healthily normal and the diseased portions of humanity.

Encouraged by the civil rights and women’s rights movement, the disability rights movement began in the 1960s. Handicapped advocacy began to have a cross-disability focus: that is, people with different kinds of disabilities—mental and physical handicaps, along with hearing and visual impairments—and a multitude of other essential needs came together to fight for a common cause. Two individuals who were in the forefront of this movement, Irving Kenneth Zola and Gunnar Dybwad, had ties to both the Howe Library and Brandeis University.

Zola was an internationally renowned sociologist and writer who specialized in medical sociology and disabilities studies. He was the Mortimer Gryzmish Professor of Human Relations at Brandeis University from 1963 until his death, in 1994. As a founding member of the Society of Disability Studies and the first editor of Disability Studies Quarterly, he was an advocate for those with disabilities. The Zola collection at Brandeis contains articles, essays, speeches, correspondence, course materials, subject files, reviews and published interviews, among other material. Topics include aging and disability, the disabled in literature, disability in the workplace and implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Gunnar Dybwad was a celebrated human-rights advocate, lawyer and administrator who was an authority on autism, retardation and cerebral palsy. He was the Professor of Human Development at Brandeis University and founder of the Starr Center for Mental Retardation at Brandeis’s Heller School as well as founder of the Autism National Committee. Dybwad is also known as one of the first in the world to frame mental disability as a civil rights matter, rather than as a medical or social-work problem. He was involved in several lawsuits in federal courts advocating civil rights for the mentally disabled.

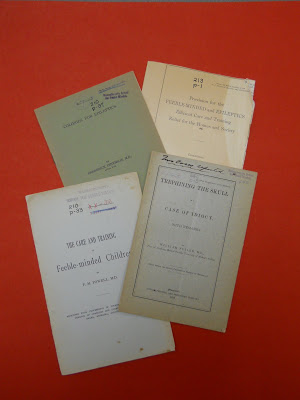

The Howe Library collection at Brandeis also includes material on the President’s Committee on Mental Retardation, a vast amount of international literature on disabilities collected by Gunnar and Rosemary Dybwad, subject files on all number of relevant topics amassed by both Dybwad and Zola, material on self-advocacy, awards and photographs, hundreds of pamphlets on disability studies from the 1870s to the 1950s, and a collection of historical books on similar subjects, many of which have been digitized and are available on the Internet Archive.

Notes

- Powell, F.M., The Care and Training of Feebleminded Children, 14th National Conference of Charities and Correction, Omaha, NE, August, 1887.

- Tallant, Alice Weld, “A Medical Study of Delinquent Girls,” speech read at the thirty-seventh annual meeting of the American Academy of Medicine, Atlantic City, May 31, 1902.

- Globe staff, “Waltham’s Fernald School to Close,” The Boston Globe, December 10, 1998.

- Davenport, C.B., Eugenics: the Science of Human Improvement by Better Breeding, Henry Hold and Company, New York, 1910.

- Goddard, Henry, “The Menace of Mental Deficiency from the Standpoint of Heredity,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. 175, number 8, August 24, 1916.

- Barker, Lewellys F., “Endocrinology,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, July 8, 1922, volume 79.