Sermones Thesauri Novi de Tempore, 1496, Bound in Hebrew Manuscript

March 28, 2008

Description by Jim Rosenbloom, Judaica Librarian

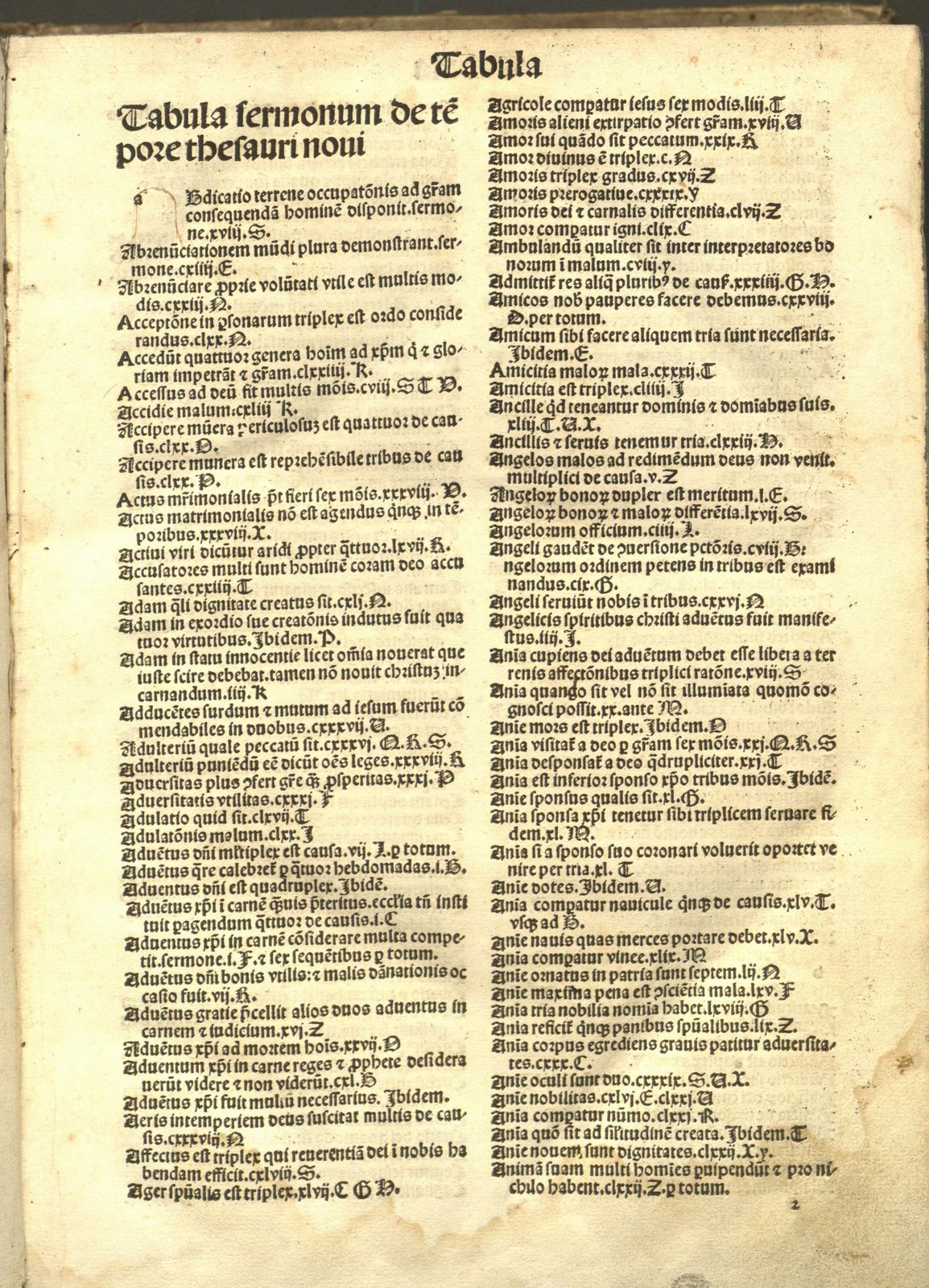

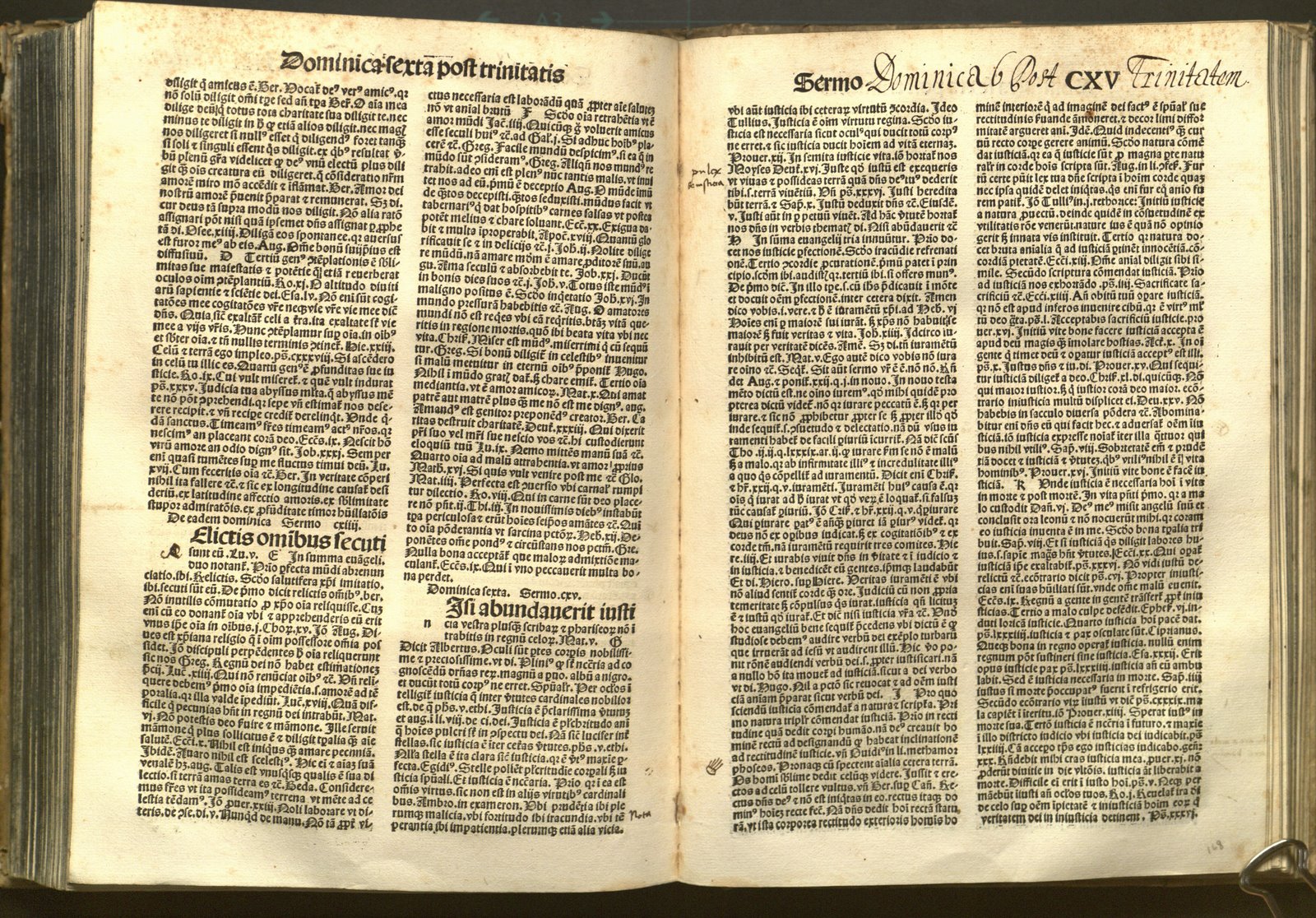

The adage “never judge a book by its cover” could have been coined to describe the work we are highlighting this month: Sermones Thesauri Novi de Tempore, by Peter Paludanus, Patriarch of Jerusalem (died 1342), published in Nuremberg by Anthonium Koberger in 1496.

The adage “never judge a book by its cover” could have been coined to describe the work we are highlighting this month: Sermones Thesauri Novi de Tempore, by Peter Paludanus, Patriarch of Jerusalem (died 1342), published in Nuremberg by Anthonium Koberger in 1496.

Peter was a French theologian and archbishop. Among his works are commentaries on all the books of the Bible and on Thomas Aquinas. He devoted most of his life to scholarship, but he did go on several important missions for the pope, who in 1329 consecrated him Patriarch of Jerusalem. He negotiated with the sultan in Egypt over the status of the Holy Land, but did not succeed in winning it back for Christianity. Around 1332 King Philip of France made him head of a group of high-ranking clergy charged to investigate the religious views of the pope, who was cleared by them of all false charges.

Our book is a collection of Peter’s sermons. Works printed through 1500 are known as incunabula (singular incunabulum, also called incunable). The word means “swaddling clothes,” connoting the early stages of printing.

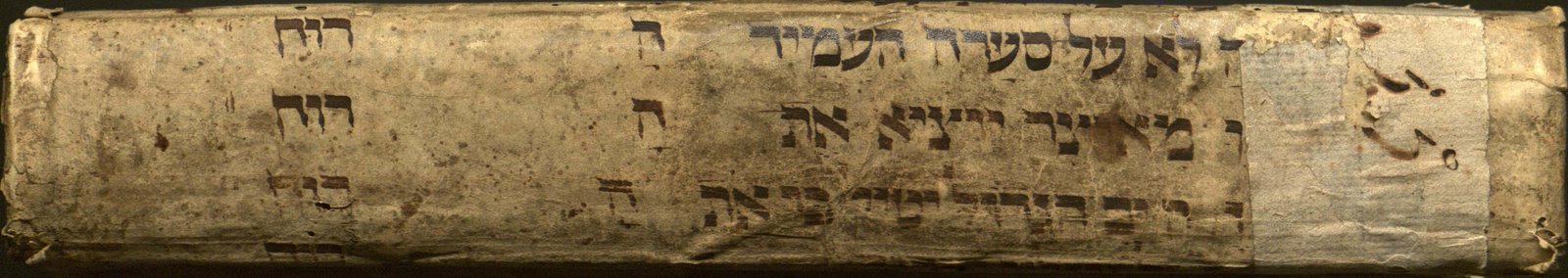

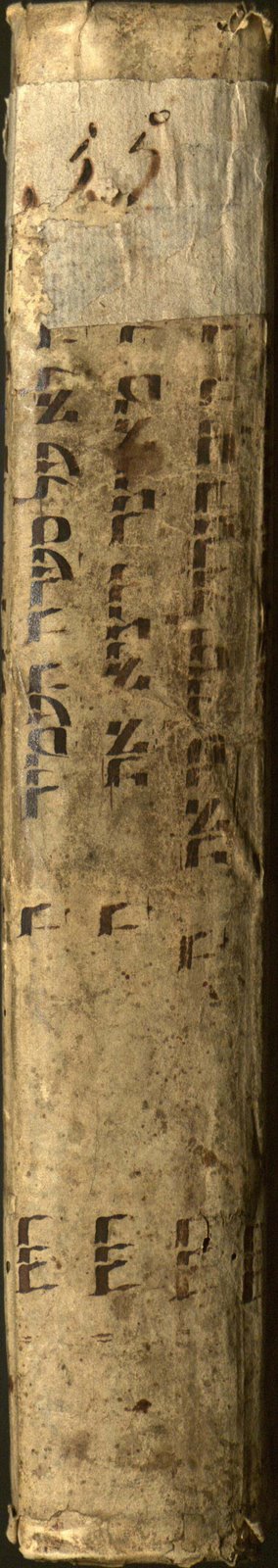

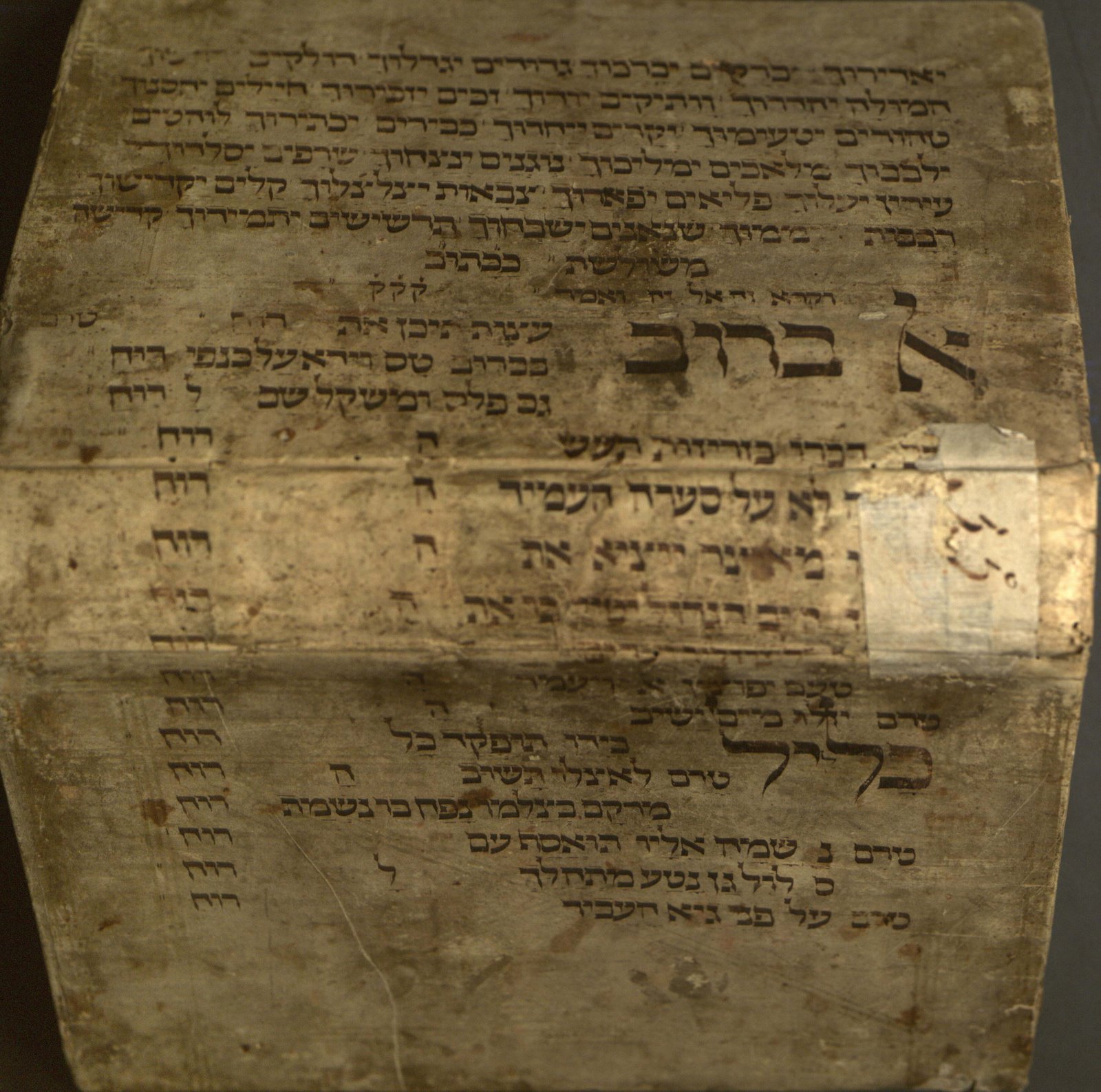

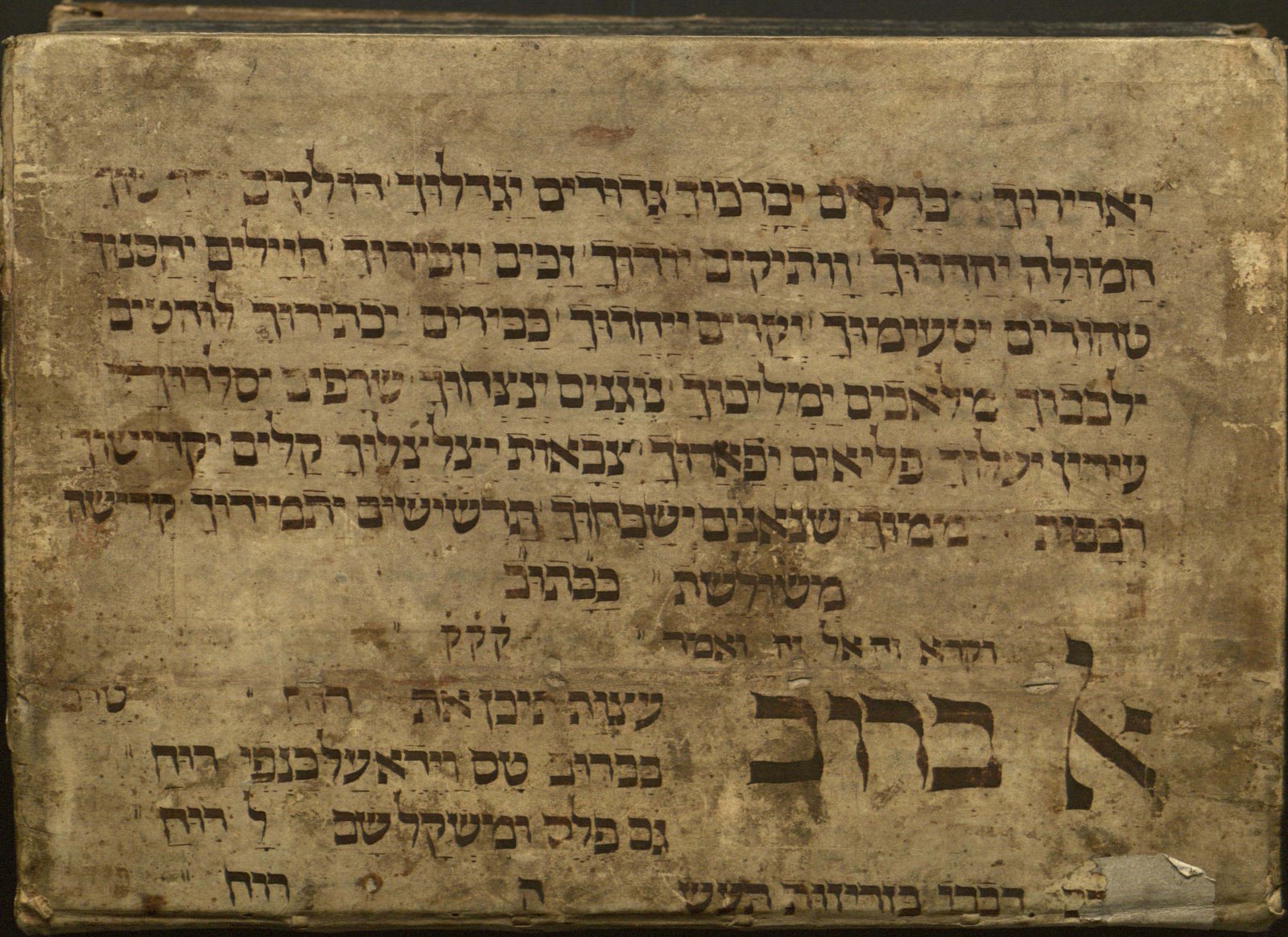

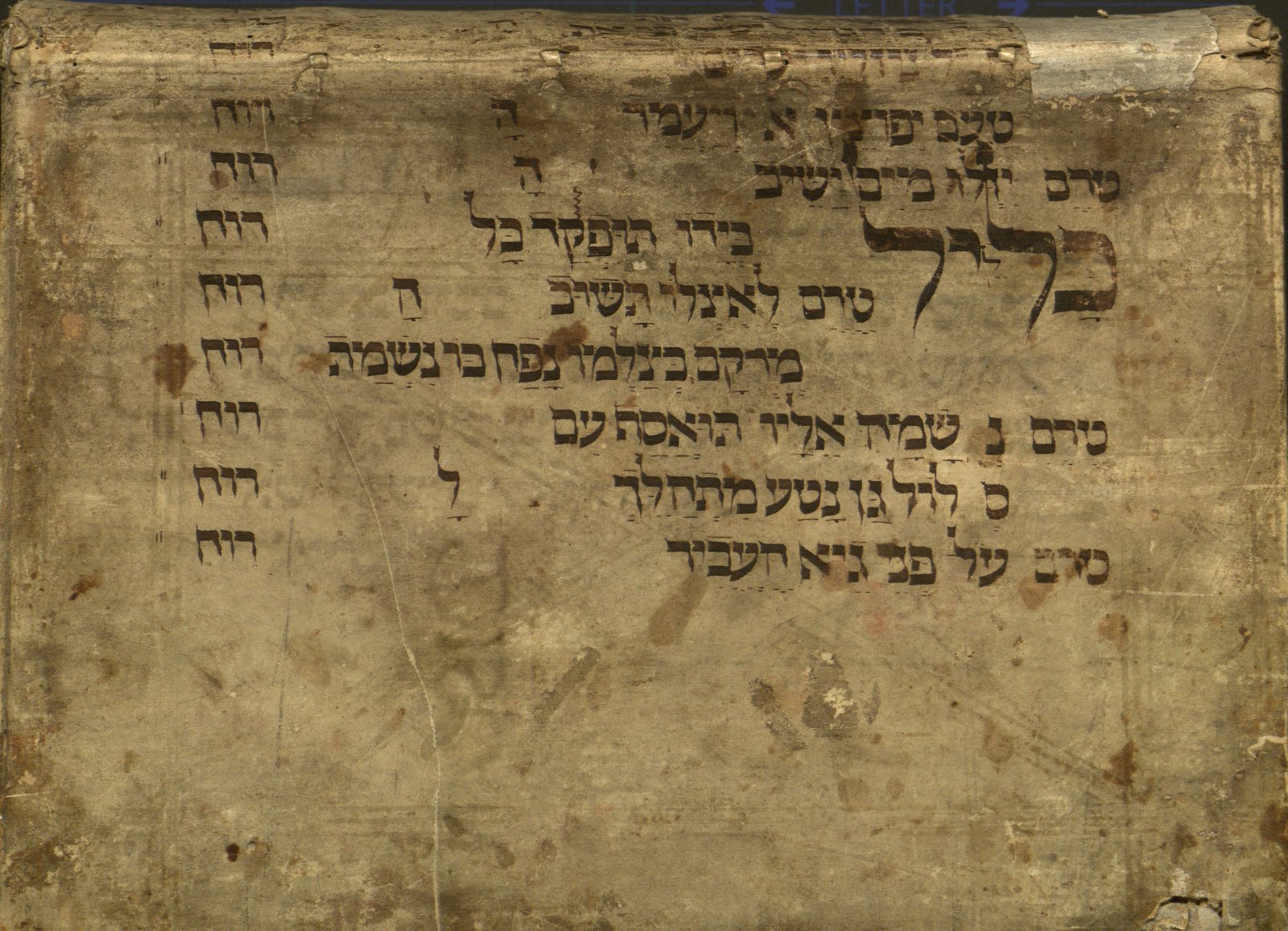

As interesting as this book is for its content, what is particularly fascinating is one of its physical features. Its outside binding is not what one might expect: it is a folio from a medieval Hebrew manuscript. The reuse of manuscripts was common in the Middle Ages; thousands of manuscripts in Latin and Greek were “recycled.” Sometimes the original ink was erased and a scribe wrote a different work on the parchment. In the 16th and 17th centuries, folios from manuscripts were also used for binding books.

As interesting as this book is for its content, what is particularly fascinating is one of its physical features. Its outside binding is not what one might expect: it is a folio from a medieval Hebrew manuscript. The reuse of manuscripts was common in the Middle Ages; thousands of manuscripts in Latin and Greek were “recycled.” Sometimes the original ink was erased and a scribe wrote a different work on the parchment. In the 16th and 17th centuries, folios from manuscripts were also used for binding books.

Hebrew manuscripts shared this fate. Undoubtedly, some Hebrew manuscripts were confiscated by the Church or by secular authorities, but in some cases they might have simply gone the way of all manuscripts, which lost their uniqueness in some people’s eyes after the invention of printing.

Hebrew manuscripts shared this fate. Undoubtedly, some Hebrew manuscripts were confiscated by the Church or by secular authorities, but in some cases they might have simply gone the way of all manuscripts, which lost their uniqueness in some people’s eyes after the invention of printing.

Over 8,000 fragments (almost all of them folio-sized rather than in small pieces) from Hebrew manuscripts have been discovered in book bindings in Italy alone, as well as about 2,000 in Germany, Austria, Hungary and Spain. They date from the 11th through the 15th centuries. Many of them, particularly those in Italy, have been preserved and studied in recent decades. It is ironic that what would seem to have been a very cavalier, and perhaps sometimes disdainful, attitude toward these manuscripts might actually have saved some of them from destruction.

One collection of such Hebrew manuscripts, found in Italy, can serve as an example of the subjects treated in these manuscript fragments: biblical text 33%; biblical commentaries 15%; Talmud and related works 8%; rabbinics 28%; philosophy and mysticism 7%; dictionaries and grammars 3%; medicine, geometry and astronomy 3%; liturgy 2%. The many Talmudic fragments are of particular importance for establishing the accurate text. Other unknown or missing works can be at least partially put together. This has already led to important scholarly discoveries.

One collection of such Hebrew manuscripts, found in Italy, can serve as an example of the subjects treated in these manuscript fragments: biblical text 33%; biblical commentaries 15%; Talmud and related works 8%; rabbinics 28%; philosophy and mysticism 7%; dictionaries and grammars 3%; medicine, geometry and astronomy 3%; liturgy 2%. The many Talmudic fragments are of particular importance for establishing the accurate text. Other unknown or missing works can be at least partially put together. This has already led to important scholarly discoveries.

The particular manuscript folio used to bind our work is taken from the liturgy of the morning Amidah for Yom Kippur. The major part is a liturgical poem by Meshullam ben Kalonymus entitled El be-Rov Etsot Tiken. Meshullam (10th to 11th centuries) was a member of one of the leading rabbinic families of Italy and a major scholar and poet. Many of his liturgical poems are still recited on Yom Kippur, including Amits Koah, which tells the story of the Yom Kippur service in the ancient Temple in Jerusalem.

The particular manuscript folio used to bind our work is taken from the liturgy of the morning Amidah for Yom Kippur. The major part is a liturgical poem by Meshullam ben Kalonymus entitled El be-Rov Etsot Tiken. Meshullam (10th to 11th centuries) was a member of one of the leading rabbinic families of Italy and a major scholar and poet. Many of his liturgical poems are still recited on Yom Kippur, including Amits Koah, which tells the story of the Yom Kippur service in the ancient Temple in Jerusalem.