Spanish Civil War Periodical Collection, 1923-2009

May 2, 2015

Description by Sean Beebe, doctoral student in History and Archives & Special Collections assistant.

From 1936-1939, Spain was wracked by a brutal civil war, sparked by a coup against its elected Second Republic. In the course of the conflict the rebelling Nationalist forces of General Francisco Franco ultimately overpowered their deeply divided Republican opponents. The conservative Nationalists profited from the military aid of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, while the Soviet Union gave a lesser degree of support to the leftist, more regional Republicans. The plight of the Republicans became a cause célèbre for the European and North American Left and for minority groups within those same societies fighting for equality. The conflict was highly mediatized and both camps and their supporters made extensive use of propaganda, resulting in the creation of huge amounts of literature and periodicals. The Nationalist victory, however, did not signal the end of publications memorializing, regretting or continuing the war. A notable part of this particular print legacy—some 394 titles produced both during and after the Spanish Civil War—is held by Brandeis University’s Special Collections.

From 1936-1939, Spain was wracked by a brutal civil war, sparked by a coup against its elected Second Republic. In the course of the conflict the rebelling Nationalist forces of General Francisco Franco ultimately overpowered their deeply divided Republican opponents. The conservative Nationalists profited from the military aid of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, while the Soviet Union gave a lesser degree of support to the leftist, more regional Republicans. The plight of the Republicans became a cause célèbre for the European and North American Left and for minority groups within those same societies fighting for equality. The conflict was highly mediatized and both camps and their supporters made extensive use of propaganda, resulting in the creation of huge amounts of literature and periodicals. The Nationalist victory, however, did not signal the end of publications memorializing, regretting or continuing the war. A notable part of this particular print legacy—some 394 titles produced both during and after the Spanish Civil War—is held by Brandeis University’s Special Collections.

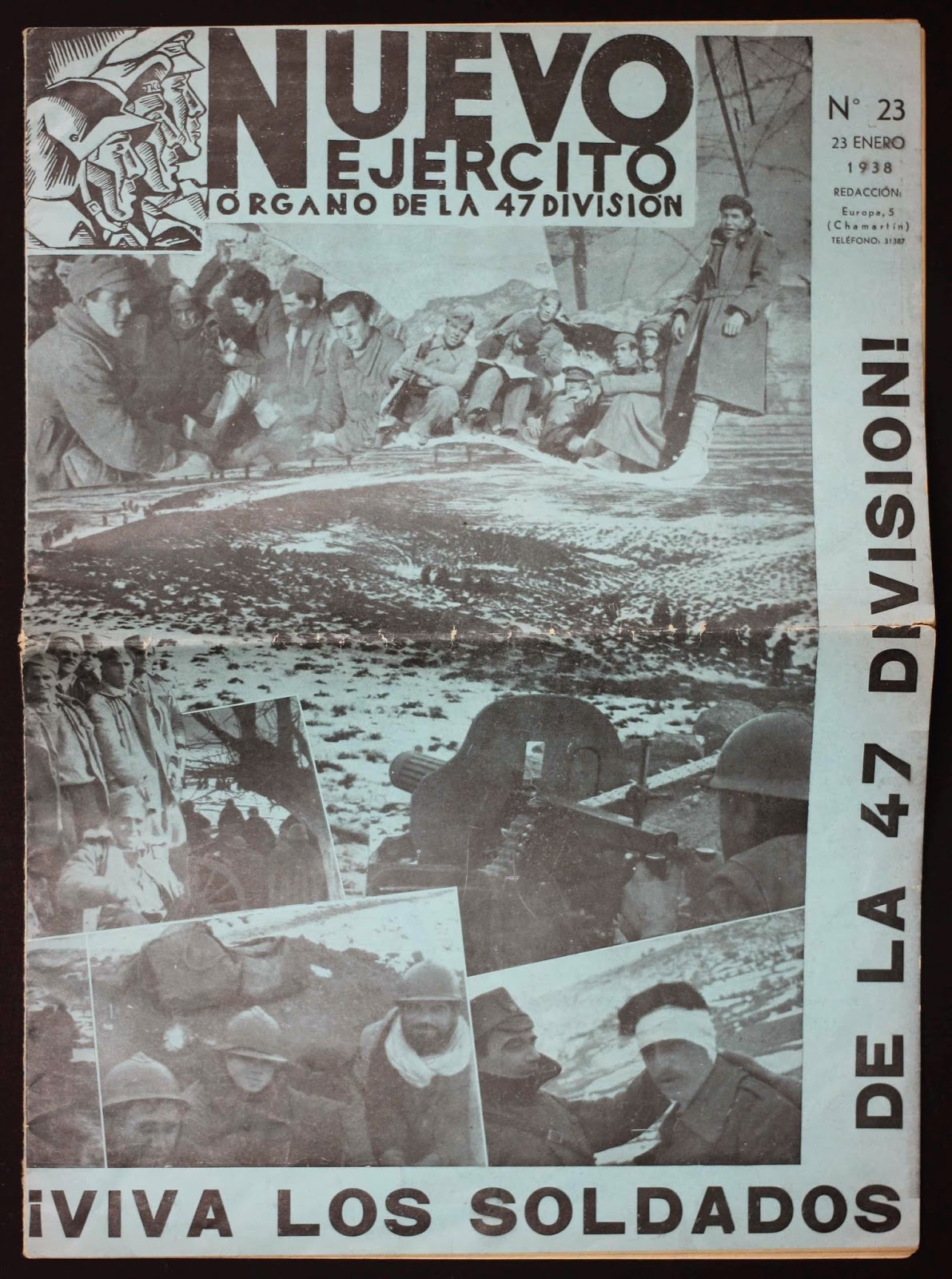

A large number of periodicals created during the Spanish Civil War were created by the fighting forces, many by particular units within those forces. These publications were intended to promote the image of those fighters and to help maintain unit morale and cohesion. The January 23, 1938 edition of Nuevo Ejercito (New Army), the newspaper of the 47th Division of the Republican army, contained a summary of the division’s recent combat activity; a Catalan-language page; and unit news, all interspersed with photographs of the division’s soldiers in winter action.

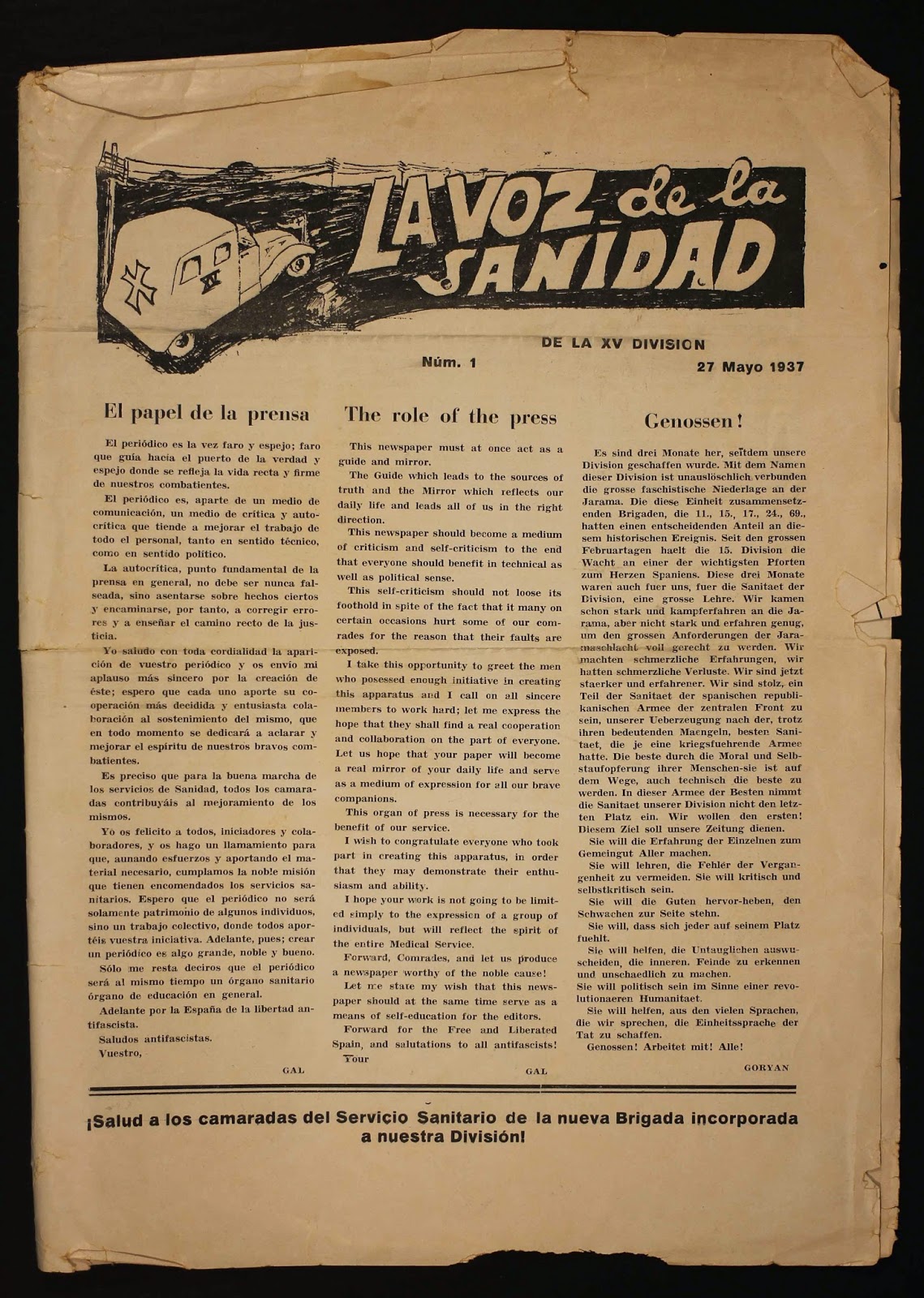

A similar approach is found in La Voz de la Sanidad, the newspaper of the international medical brigade attached to the 15th Division. Befitting the brigade’s multinational status, the paper was written in four languages: Spanish, French, English and German. La Voz de la Sanidad’s content consisted of a mixture of the same items reproduced—side-by-side or on succeeding pages—in each of the four languages, alongside items, both informative and comic, unique to each language.

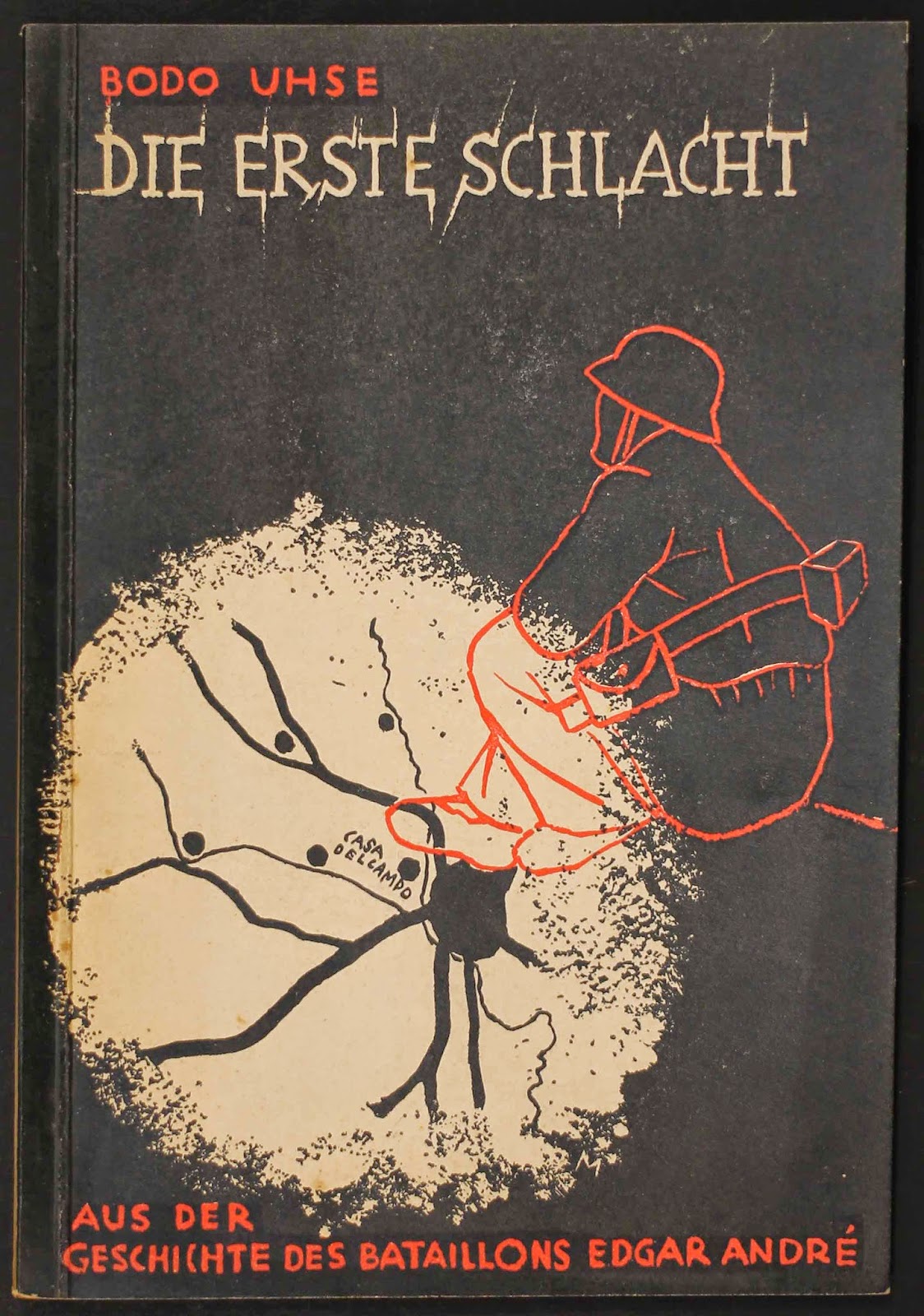

A third example of such a text is Die erste Schlacht (The First Battle), a 1938 account of the early days of the Edgar André Battalion — the first battalion of the International Brigades, named after a German Communist executed by the Nazi regime — by the German Communist writer and International Brigades officer, Bodo Uhse. Uhse’s short book, written in German and published in the French city of Strasbourg, strove to commemorate those who had fallen in fighting on the side of the Republicans and encourage those Germans who, in opposition to fascism, might find cause with them.

A third example of such a text is Die erste Schlacht (The First Battle), a 1938 account of the early days of the Edgar André Battalion — the first battalion of the International Brigades, named after a German Communist executed by the Nazi regime — by the German Communist writer and International Brigades officer, Bodo Uhse. Uhse’s short book, written in German and published in the French city of Strasbourg, strove to commemorate those who had fallen in fighting on the side of the Republicans and encourage those Germans who, in opposition to fascism, might find cause with them.

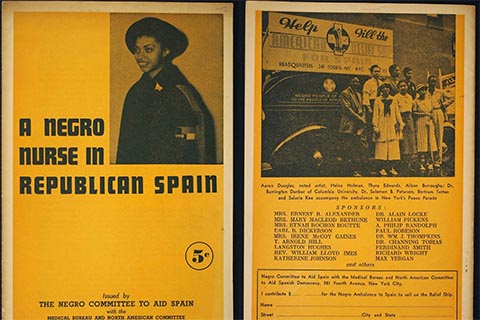

A second type of periodical served to call for material support for the Republican side. In New York City, African-Americans combined this support with efforts to combat racism at home. The Negro Committee to Aid Spain, sponsored by such notables as Mary McLeod Bethune, Langston Hughes, A. Philip Randolph, Paul Robeson, and Richard Wright, published a pamphlet entitled “A Negro Nurse in Republican Spain,” which recounted the story of Salaria Kee, an African-American nurse from Harlem who joined the volunteer American Medical Unit in 1937.

Kee’s story was juxtaposed with a more general account of those of African-American men who had volunteered for the International Brigades, as racism at home “appeared to them as part of the picture of fascism,” which could be most directly confronted in Spain. The pamphlet chronicled Kee’s early life, decision to go to Spain and her service there, both in hospitals and directly behind the lines — until a shell wound made her unfit for further service. Kee returned to America, and joined the fundraising campaign for which the pamphlet was produced. The text concluded with a quotation from Kee: “Negro men have given up their lives there…as courageously as any heroes of any age. Surely Negro people will just as willingly give of their means to relieve the suffering of a people attacked by the enemy of all racial minorities — fascism — and its most aggressive exponents — Italy and Germany.”

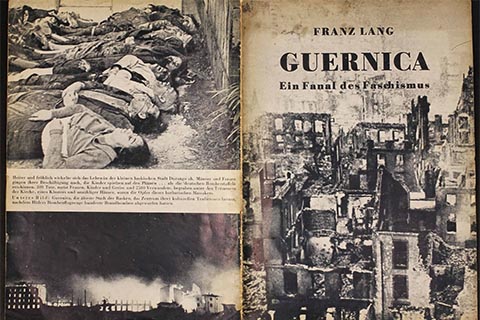

An additional example of this type of publication is the German-language pamphlet, “Guernica...Ein Fanal des Faschismus” (A Beacon of Fascism), produced after the bombing of that city. The text excoriated the fascist “beast” for the destruction wrought upon the Basque people, and called for direct material aid to the Basques so that they might succeed in the defense of their “freedom” in the face of fascist aggression.

An additional example of this type of publication is the German-language pamphlet, “Guernica...Ein Fanal des Faschismus” (A Beacon of Fascism), produced after the bombing of that city. The text excoriated the fascist “beast” for the destruction wrought upon the Basque people, and called for direct material aid to the Basques so that they might succeed in the defense of their “freedom” in the face of fascist aggression.

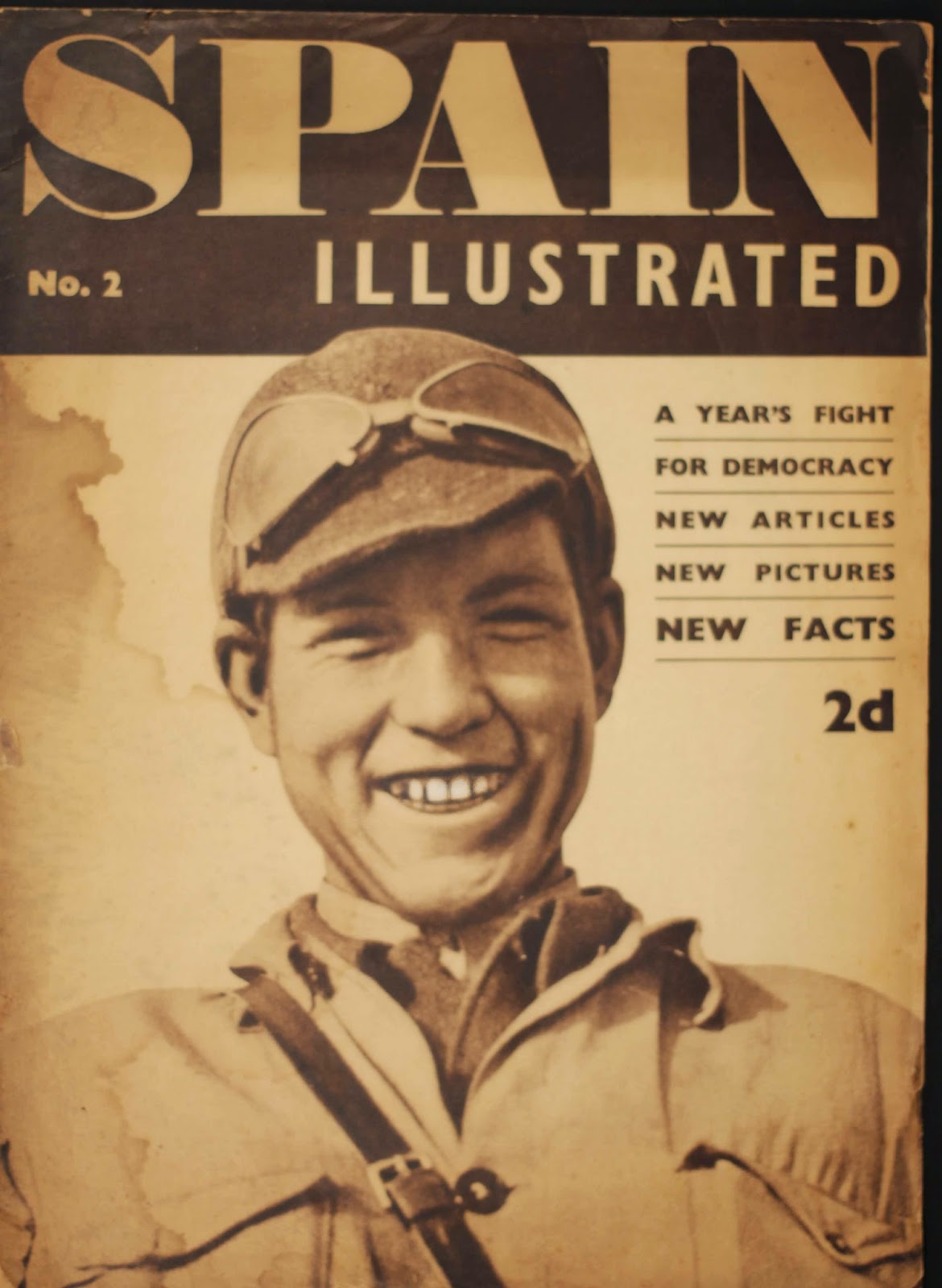

One further form of publication, that of outright propaganda designed to influence hearts and minds, forms an extensive part of the collection. A 1937 edition of the British magazine Spain Illustrated featured photographs (including those of corpses) and articles portraying “a year’s fight for democracy,” and condemning the Nationalists and their fascist backers for the tremendous suffering inflicted upon the Spanish people. The non-interventionist policy of the Western democracies was vilified as an utter failure, with Parliament coming in for particular criticism for its “pro-fascist” stance. Most dramatically, the magazine contended that the defeat of the Republicans would be but the prelude “for attacking England and France…all hope of peace in Europe would be at an end.”

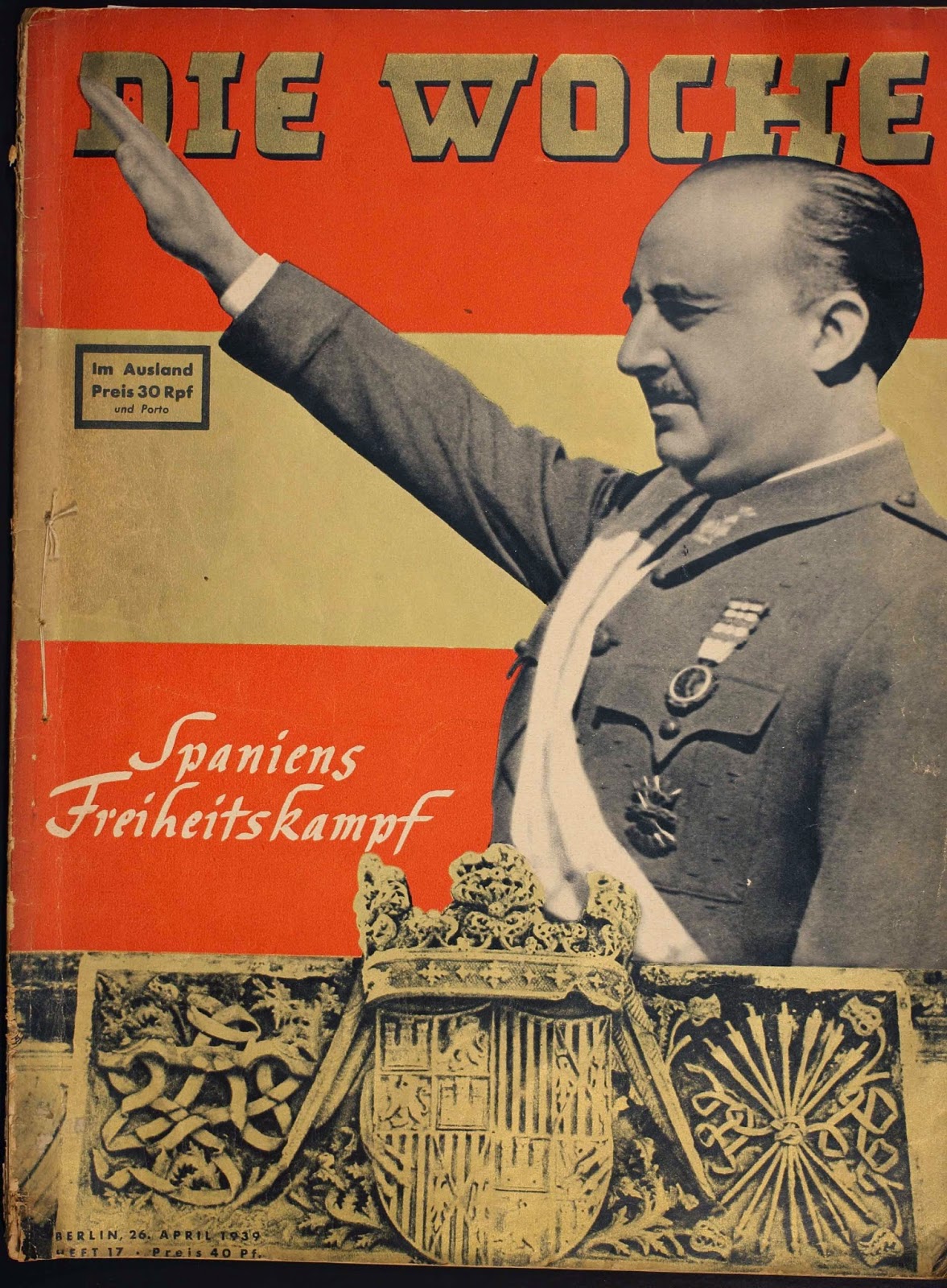

The April 26, 1939 edition of the German magazine Die Woche (The Week), on the other hand, had two celebrations to highlight: Hitler’s 50th birthday, and Franco’s triumph in the war, significant enough for the saluting Spanish commander’s photograph to dominate the cover, with the headline “Spaniens Freiheitskampf” (“Spain’s fight for freedom”). Inside, Franco was depicted as a “fighter for honor and freedom,” while Germany and Italy were said to “offer the hand of friendship” to the Spanish nation. International assistance to Spain was labeled as “Bolshevik,” and, under a photograph of British International Brigade volunteers, the magazine wondered why the British were engaged alongside “the Reds.”

The April 26, 1939 edition of the German magazine Die Woche (The Week), on the other hand, had two celebrations to highlight: Hitler’s 50th birthday, and Franco’s triumph in the war, significant enough for the saluting Spanish commander’s photograph to dominate the cover, with the headline “Spaniens Freiheitskampf” (“Spain’s fight for freedom”). Inside, Franco was depicted as a “fighter for honor and freedom,” while Germany and Italy were said to “offer the hand of friendship” to the Spanish nation. International assistance to Spain was labeled as “Bolshevik,” and, under a photograph of British International Brigade volunteers, the magazine wondered why the British were engaged alongside “the Reds.”

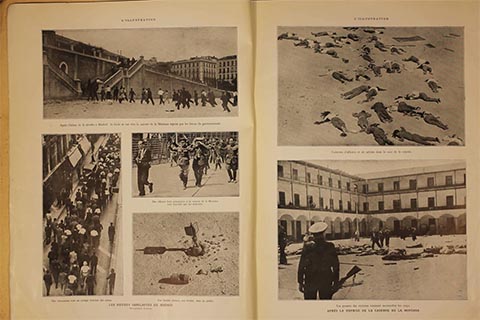

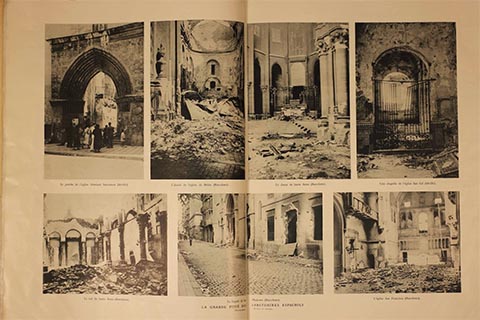

Finally, the example of quasi-neutral international media opens an interesting window on to how the conflict was perceived outside of Spain, outside of an obvious ideological lens. In August 1936, the famed French illustrated magazine, L’Illustration, published a special edition dedicated to the civil war. L’Illustration’s version of the war was one of utter tragedy, in which “fratricidal” conflict split the nation apart; its editors “could only see in the two Spains in conflict a single country which we love and which suffers.” Consequently, the magazine presented images of the conflict’s devastation, whether the rather graphic images of corpses left in public places, those of defiled churches, or of cities after bombardments and shelling. These particularly dramatic choices appear to serve an almost fatalistic reading of the conflict, in which no action can be taken but to observe this tremendous amount of suffering.

L’Illustration and the other publications cited are but a small part of the Spanish Civil War periodicals collection, which serves to present the passions and problematics of this conflict, in both its trauma and its international resonance.

L’Illustration and the other publications cited are but a small part of the Spanish Civil War periodicals collection, which serves to present the passions and problematics of this conflict, in both its trauma and its international resonance.

Resources

Brandeis University's Archives & Special Collections holds a significant amount of material relating to the Spanish Civil War, including over 4,700 books, close to 400 periodicals and roughly 250 posters. In addition, the Charles Korvin photograph collection comprises 244 black and white images taken during the War. Follow the links below for further information about these holdings:

Spanish Civil War periodical collection, 1923-2009 (finding aid)

Charles Korvin photographs, circa 1937-1938 (finding aid)

Spanish Civil War posters, 1936-1938 on Brandeis University’s Institutional Repository