“The Three Ages of the Colonies” from the Book Collection of Charles J. Tanenbaum

March 29, 2013

Translations and description by Drew Flanagan, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in History

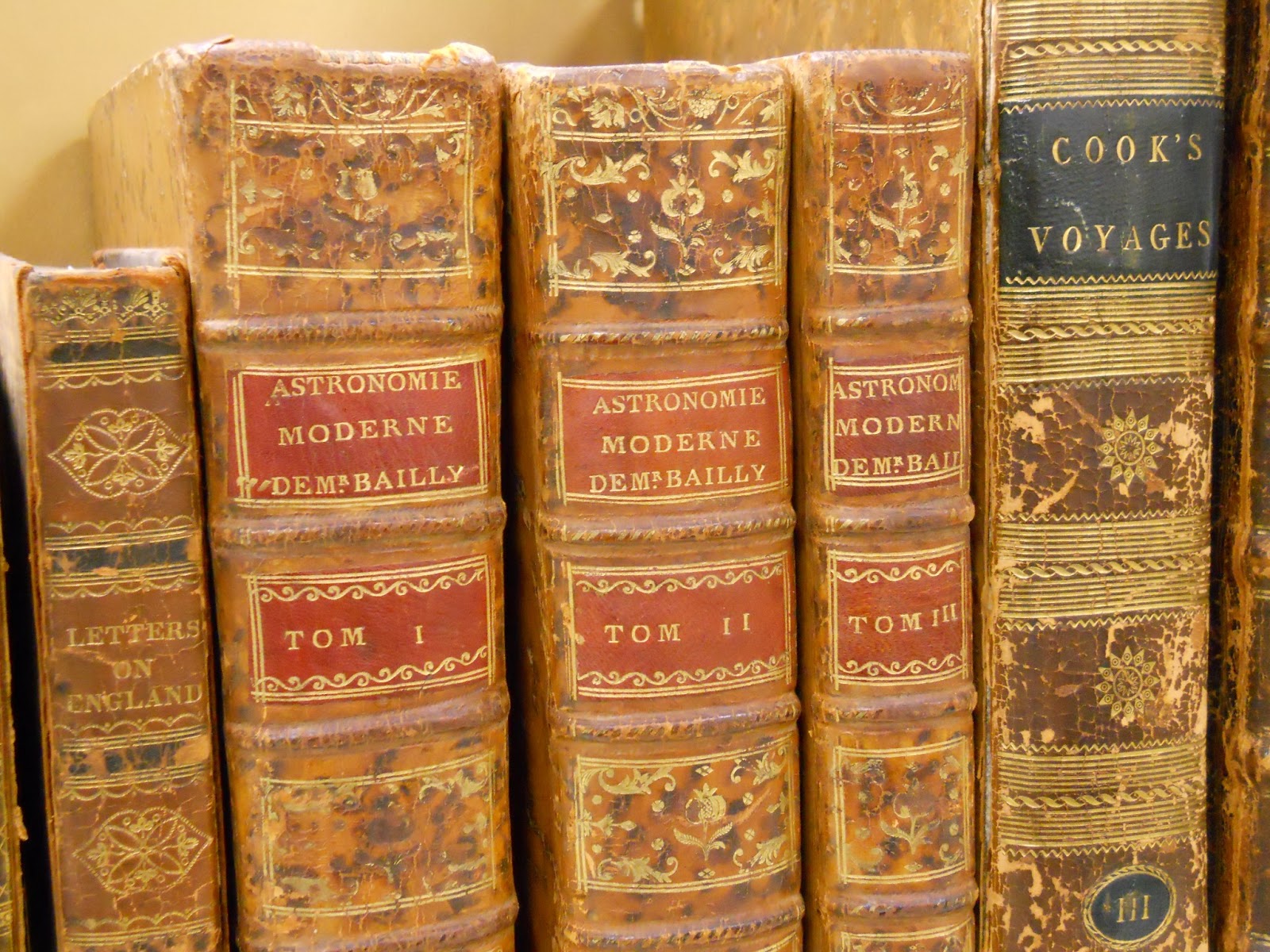

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis is pleased to have received a donation of rare books from the collection of Charles J. Tanenbaum, noted bibliophile and father of Ann Tanenbaum, Brandeis class of 1966. The collection comprises some 30 rare texts spanning four centuries, including a 1652 work of cosmography, a 1742 book of law for “the inhabitants of the province of Massachusetts-Bay,” a 1785 edition and atlas of Captain Cook’s “A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean” and much more, from geography and exploration to religion and politics, from Machiavelli to Daniel Defoe.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis is pleased to have received a donation of rare books from the collection of Charles J. Tanenbaum, noted bibliophile and father of Ann Tanenbaum, Brandeis class of 1966. The collection comprises some 30 rare texts spanning four centuries, including a 1652 work of cosmography, a 1742 book of law for “the inhabitants of the province of Massachusetts-Bay,” a 1785 edition and atlas of Captain Cook’s “A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean” and much more, from geography and exploration to religion and politics, from Machiavelli to Daniel Defoe.

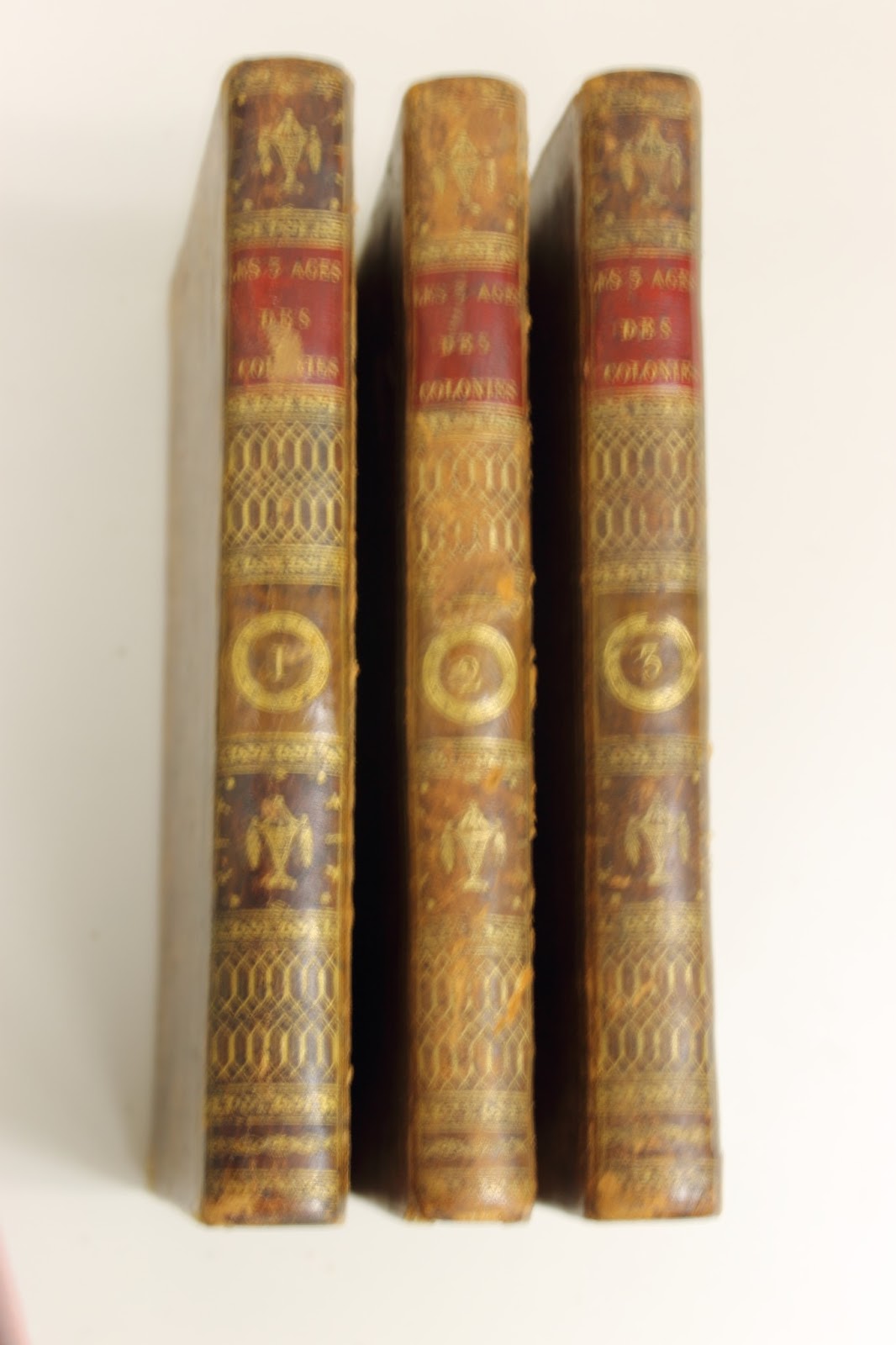

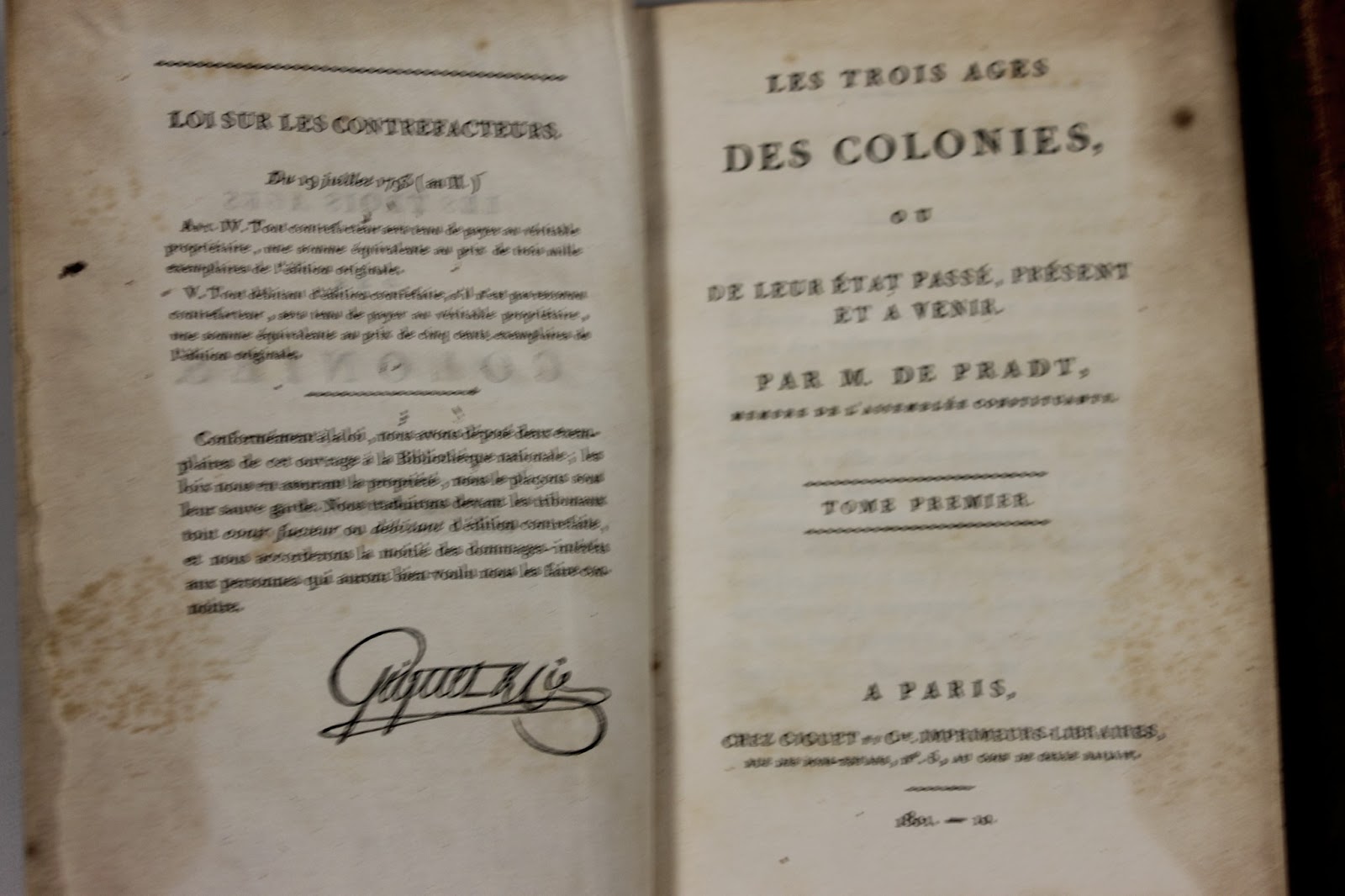

The collection is rich in works from the 18th century. Several of these works, as one would expect from the time period, relate to European colonization in the 1700s, mostly British but also French. One such work in the collection is Dufour de Pradt’s three-volume 1801 work “Les trois ages des colonies, ou de leur état passé, présent, et à venir,” which addresses the crisis of the French colonial empire that accompanied the Napoleonic wars.

At the intersection of religion and politics, and sharing with Machiavelli a strong commitment to statecraft and to his own advancement, the Abbé Dominique-Georges-Frédéric Dufour de Pradt had a political and ecclesiastical career that spanned the French revolutionary period. His work was published in the year in which French forces were defeated and driven from the colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) by the world’s first and only successful slave revolution. While French forces returned to the colony within the year, capturing the rebel leader Toussaint Louverture, attempts by the reconstituted French colonial authorities to reinstate slavery were met with a second, final armed rebellion led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines. The last French troops were to leave Saint-Domingue in 1803, the same year that a militarily overstretched France was to sell its north American holdings (Louisiana, or New France) to the United States.

Dufour de Pradt’s first volume begins by calling attention to the impending collapse of Europe’s colonial empires. “While Europe, absorbed by the duration, the importance and the singularity of the scenes that are going on within her, concentrates all of her attention on herself, the principal source of her riches is going to dry up, and her colonies are on the brink of escaping her” (i). His introduction acknowledges the profound impact of the French revolution on the colonies not only of France, but also of Britain, the Netherlands, Spain and Denmark. His work takes the form of a history of the “three ages” of European colonization, beginning in the 15th century. “Three hundred years have sufficed to bring about this surprising metamorphosis, and these three hundred years have done more for the well-being of the world than the six-seven centuries that preceded them. The end of the 15th [century] saw the aurora of that revolution: it died at dusk of a new day that would shine in the universe” (21). Dufour de Pradt goes on to honor Vasco da Gama and Columbus, whose opposite routes each brought them to one of the two Indies and thus set in motion the process of colonization.

Dufour de Pradt’s first volume begins by calling attention to the impending collapse of Europe’s colonial empires. “While Europe, absorbed by the duration, the importance and the singularity of the scenes that are going on within her, concentrates all of her attention on herself, the principal source of her riches is going to dry up, and her colonies are on the brink of escaping her” (i). His introduction acknowledges the profound impact of the French revolution on the colonies not only of France, but also of Britain, the Netherlands, Spain and Denmark. His work takes the form of a history of the “three ages” of European colonization, beginning in the 15th century. “Three hundred years have sufficed to bring about this surprising metamorphosis, and these three hundred years have done more for the well-being of the world than the six-seven centuries that preceded them. The end of the 15th [century] saw the aurora of that revolution: it died at dusk of a new day that would shine in the universe” (21). Dufour de Pradt goes on to honor Vasco da Gama and Columbus, whose opposite routes each brought them to one of the two Indies and thus set in motion the process of colonization.

Dufour de Pradt relates European colonization to contemporary developments in science, social science and technology, part of “a new intellectual universe” that opened for the human race beginning in the late 15th century. He recognizes the importance of exploration and colonization in the development of that new knowledge, as “astronomy, physics, navigation, art, botany, knowledge of [man’s] own species, all accrued and were corrected along with it.”(22) In successive chapters, Dufour de Pradt tells the triumphal story of this revolution in human affairs. His second chapter describes how Portugal, “unknown in Europe, became all of a sudden a colossus in Asia.”(27) His first volume covers the economic, political and military aspects of colonization, and successive chapters address the Dutch, British, French and Spanish empires. The first volume concludes with a chapter addressing the total material benefits accrued by the various colonizing powers, a fitting capstone to a narrative that presents colonization primarily as a pan-European modernizing and money-making enterprise.

Dufour de Pradt relates European colonization to contemporary developments in science, social science and technology, part of “a new intellectual universe” that opened for the human race beginning in the late 15th century. He recognizes the importance of exploration and colonization in the development of that new knowledge, as “astronomy, physics, navigation, art, botany, knowledge of [man’s] own species, all accrued and were corrected along with it.”(22) In successive chapters, Dufour de Pradt tells the triumphal story of this revolution in human affairs. His second chapter describes how Portugal, “unknown in Europe, became all of a sudden a colossus in Asia.”(27) His first volume covers the economic, political and military aspects of colonization, and successive chapters address the Dutch, British, French and Spanish empires. The first volume concludes with a chapter addressing the total material benefits accrued by the various colonizing powers, a fitting capstone to a narrative that presents colonization primarily as a pan-European modernizing and money-making enterprise.

The second volume of Dufour de Pradt’s book addresses the current state of the colonial empires in 1801. He begins by addressing issues pertaining to the colonies in general, then looks more closely at the case of each of several colonies in particular. In general, he says,

The colonies are children that have left, or been taken from, the paternal home, for a thousand different reasons. Here, it is the anger of the father that isolates them, and that forces them to search elsewhere for asylum. There, it is the family that is too numerous that separates itself in order to find relief, and that will search outside of its foyers for the sustenance that it has deprived the paternal home of. Elsewhere, it is the sadness of war, of civil dissensions, the vengeance of one part of the citizenry against the other, the ambition to aggrandize or enrich themselves, that has given birth to colonies (v. 2, 7).

For all of these reasons, Dufour de Pradt argues, Europeans have been compelled to take on colonies since ancient times. Yet he carefully distinguishes between colonization in the ancient world and in the modern one. The ancients “surpassed the moderns in truly colonial ideas,” due to the generosity of their outlook and treatment of those they colonized. In essence, the ancients allowed their colonies to be or to become free and independent and did not allow one organization (such as the various East India companies) to monopolize their trade (v. 2, 13). Here begins a surprising shift in emphasis, from the positive economic and political effects of colonization to the exigencies of colonial reform in the face of decline.

Dufour de Pradt seeks to lay out the reasons for the current state of affairs, in order to suggest the outlines of a more productive future colonial regime. He roundly criticizes the existence of trade monopolies (compagnies exclusifs) and advocates as an alternative “freedom of commerce.” He then shifts to the topic of slavery. Although he mentions the “manifest inferiority” of the education of black slaves and the source of the need for a slave trade in the depopulation of the Indians, he approaches the question of what to do about the slave trade as a matter of the fate of the colonial empires rather than as a moral question. “In abandoning all of the metaphysics of the legitimacy of slavery, we confine ourselves to saying that there was nothing in between the trade and the abandonment of the colonies; that it is necessary to choose between them” (v. 2, 60). To free the slaves would be to render the colonies useless for economic purposes, and those who advocate their liberty must be aware that they also are advocating the end of the colonies. He follows this observation with a long and fascinating discussion of his nuanced and original views on the state of the slaves and of the Europeans in the colonies. What emerges from this second volume is an argument in favor of the independence of the colonies, based both on the example of the ancients and on the exigencies of the present situation.

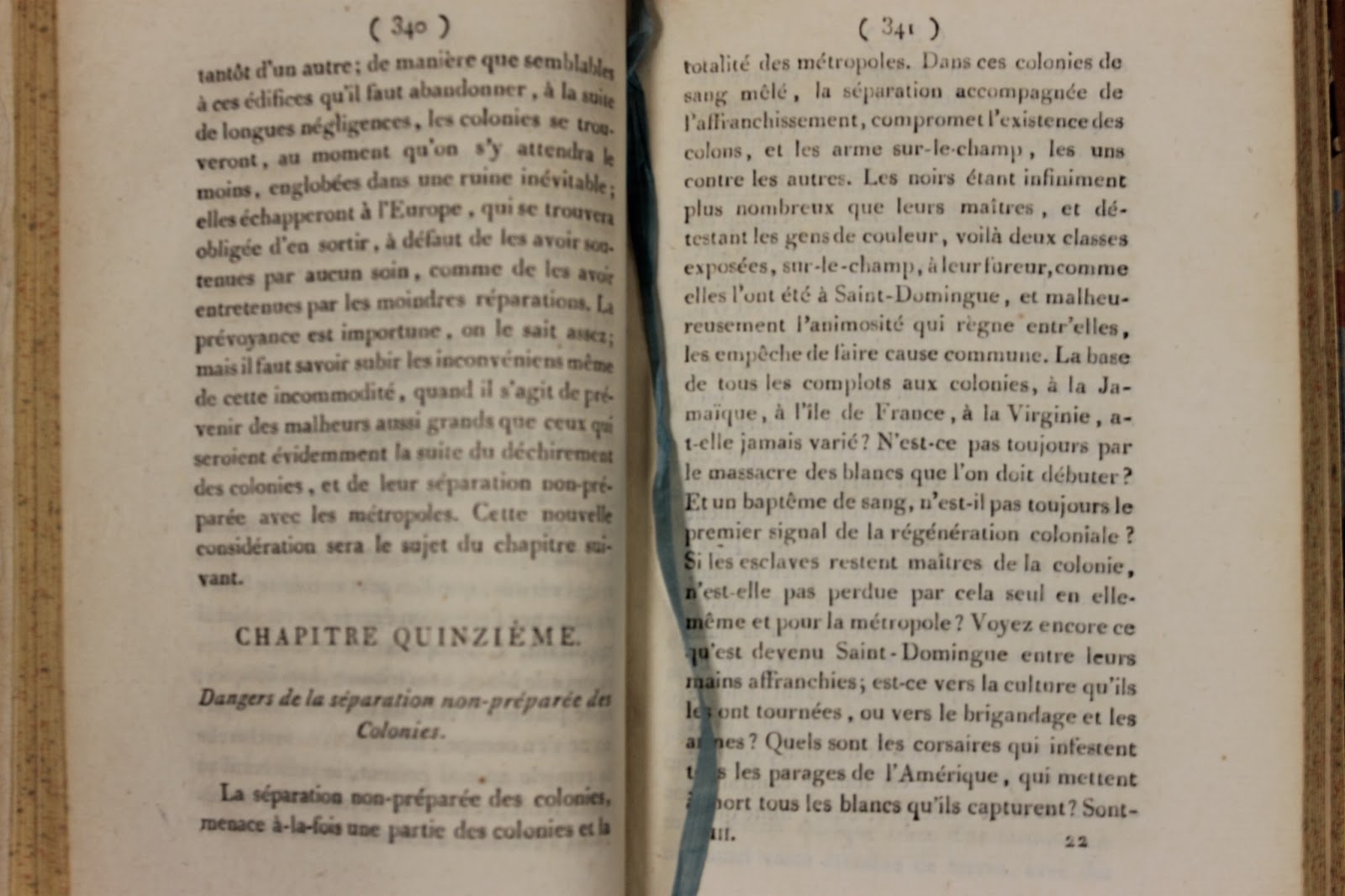

The third volume of the work addresses the “necessity of a change in the colonies” directly. Dufour de Pradt lays out a more hopeful vision of the current state of the colonies, underlining the degree to which they have grown to be able to manage their own affairs. As an example of the strength of the colonists, he cites the resistance of “two million five hundred thousand” residents of English America (the United States) against the full forces of the British Empire (v. 3, 283). He closely analyzes the economic and political strength of one colony after another, assessing how close they are to be ready to stand on their own. Not advocating a sudden cutting-loose of the European colonists, he spends an entire chapter addressing the “dangers of the unprepared separation of the colonies” (v. 3, 340). Using the example of Saint-Domingue, he notes that peoples who are not ready to become free tend toward “brigandage and arms” rather than culture and civilization (v. 3, 341). His detailed plan for decolonization in the Americas, presented as representing “the true interest of Europe, without the exception of any state or country” (vol. 3, 475), will be of great interest to scholars of French history and of the history of the Americas in the age of revolutions. Dufour de Pradt’s conception of Europe is reflected in a number of suggestive lines that are worthy of some interest in their own right. He concludes his work with the following:

The third volume of the work addresses the “necessity of a change in the colonies” directly. Dufour de Pradt lays out a more hopeful vision of the current state of the colonies, underlining the degree to which they have grown to be able to manage their own affairs. As an example of the strength of the colonists, he cites the resistance of “two million five hundred thousand” residents of English America (the United States) against the full forces of the British Empire (v. 3, 283). He closely analyzes the economic and political strength of one colony after another, assessing how close they are to be ready to stand on their own. Not advocating a sudden cutting-loose of the European colonists, he spends an entire chapter addressing the “dangers of the unprepared separation of the colonies” (v. 3, 340). Using the example of Saint-Domingue, he notes that peoples who are not ready to become free tend toward “brigandage and arms” rather than culture and civilization (v. 3, 341). His detailed plan for decolonization in the Americas, presented as representing “the true interest of Europe, without the exception of any state or country” (vol. 3, 475), will be of great interest to scholars of French history and of the history of the Americas in the age of revolutions. Dufour de Pradt’s conception of Europe is reflected in a number of suggestive lines that are worthy of some interest in their own right. He concludes his work with the following:

It is in European, it is in French that we have written, we would like to repeat; we do not want to, we cannot recognize any other titles; it would be equally outside of our line and of our intentions, and we do not deviate also from the sentiments that we attach to Europe in general, those that we attach to France in particular. Happy if our weak voice can pierce through to her, traversing the tumult of arms and the agitations of a revolution with which her soil quivers again!

Whether read as a cry for peace in Europe, for the liberation of the New World, or for the development of free trade, these volumes are full of insights into Dufour de Pradt’s thought and his times.