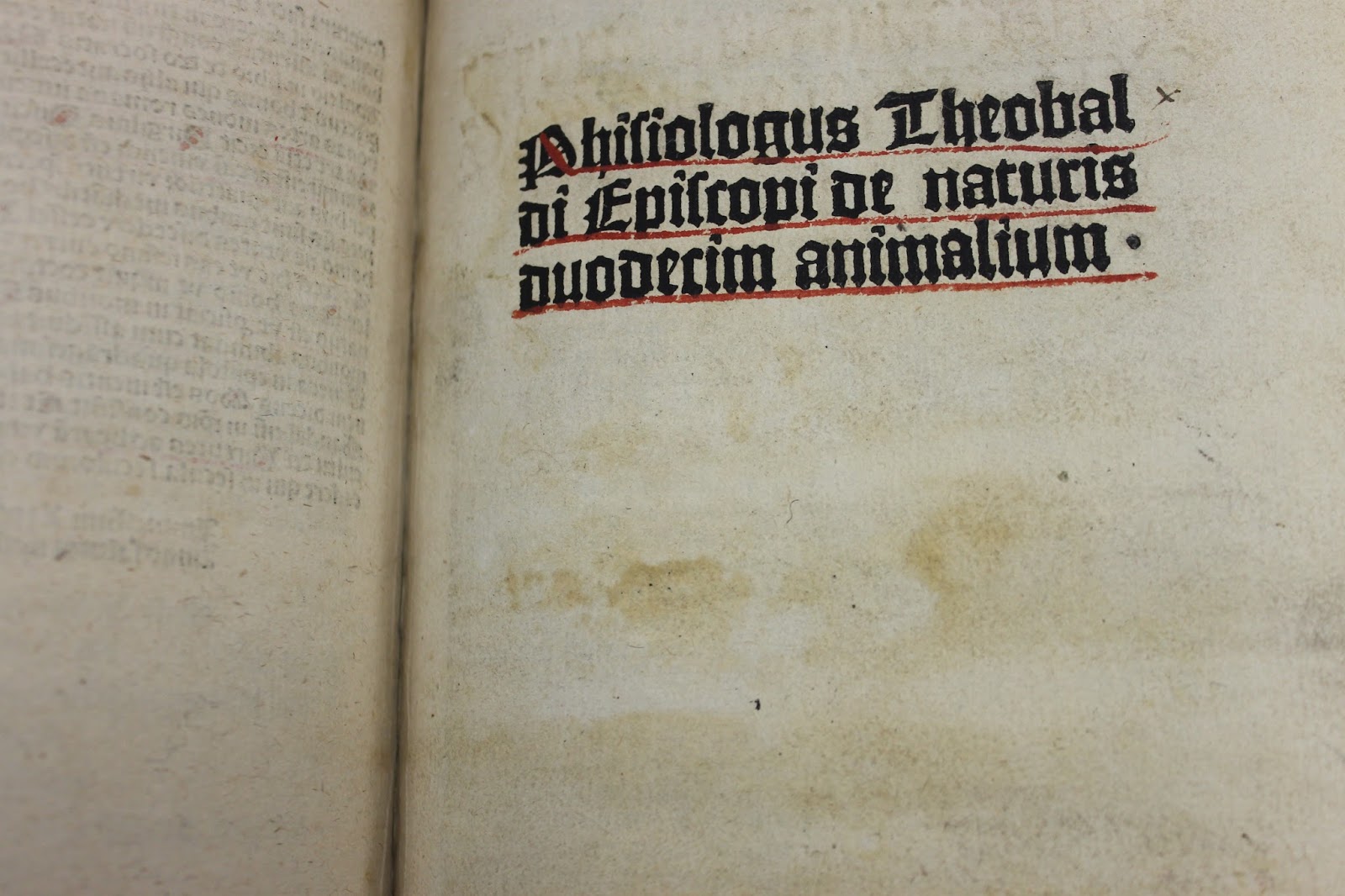

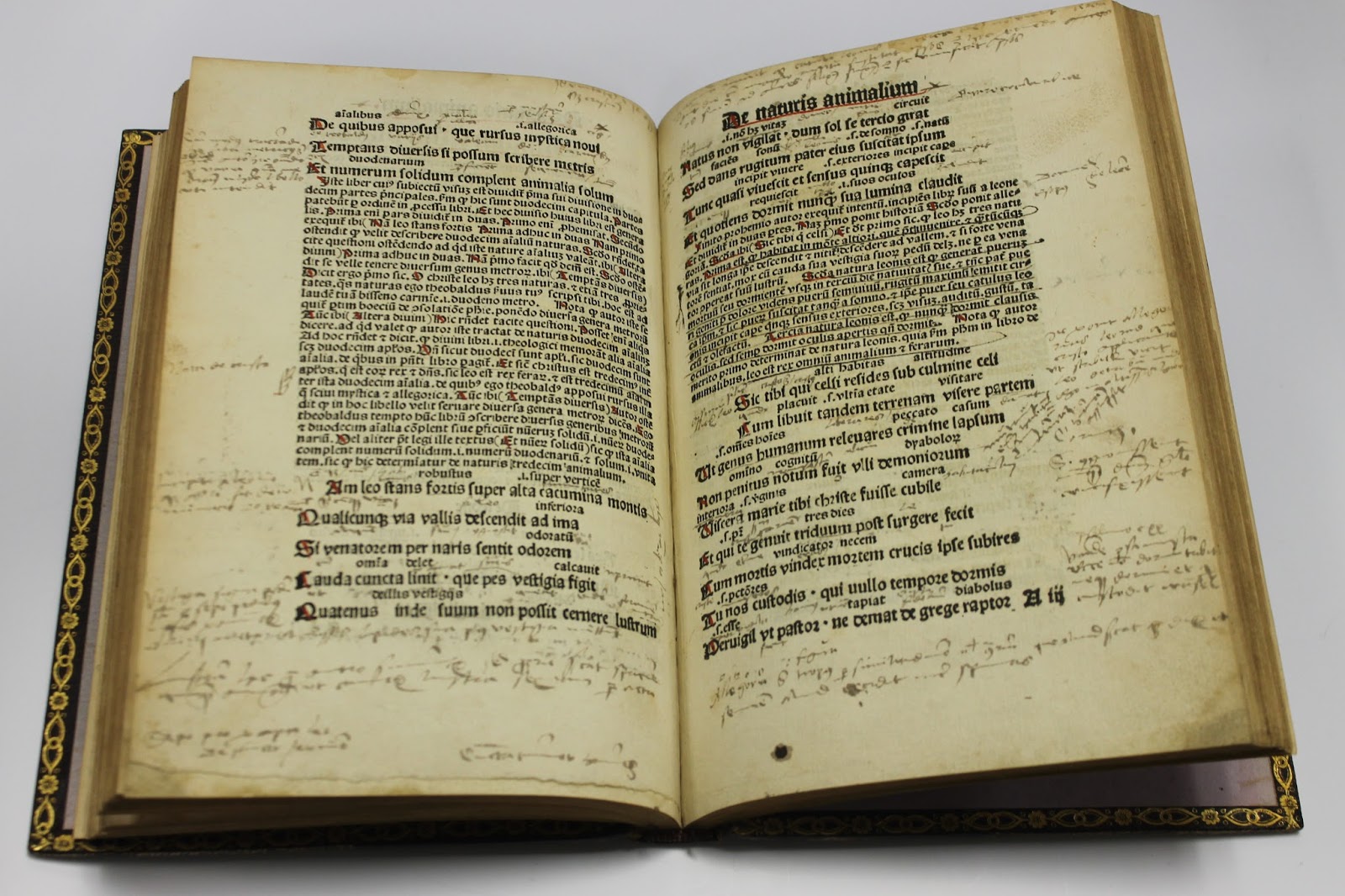

Theobaldus' Phisiologus de Naturis Duodecim Animalum, 1493

April 1, 2017

Description by Katie Graff, MA student in Classical Studies and Archives and Special Collections assistant.

Precursors of the fantastical and brightly-illuminated bestiaries of later medieval times, physiologia were didactic and allegorical Christian texts which presented a catalog of the history and lore of the natural world. While these manuscripts would hardly be recognizable to a modern audience as reliable sources of scientific or zoological information, they have nevertheless been enjoyed throughout the centuries by scholars, theologians and the casual page-turner alike.

Precursors of the fantastical and brightly-illuminated bestiaries of later medieval times, physiologia were didactic and allegorical Christian texts which presented a catalog of the history and lore of the natural world. While these manuscripts would hardly be recognizable to a modern audience as reliable sources of scientific or zoological information, they have nevertheless been enjoyed throughout the centuries by scholars, theologians and the casual page-turner alike.

The roots of physiologia go back to Late Antiquity. Though scholars debate the exact date of the first physiologus, most agree it was created in Egypt between the first and second centuries C.E. The earliest known physiologus featured stories that would become hallmarks of these texts and the later illuminated bestiaries which followed them. Some of the first known tales of mythological creatures — such as that of the phoenix rising from its own ashes — as well as mythological tales of real animals — like that of the pelican shedding blood onto its young to revive them — are contained in this text.

Though physiologia delighted readers of all ages, these compendia were especially valuable as teaching tools for young children. Because of its versatility and whimsical, entertaining nature, the physiologus is thought to have been the widest-circulated form of literature, after the Bible, for most of the Middle Ages. Though common allegorical notions and lore for particular animals connect across each version, each physiologus is unique and often anonymously authored. Each scribe imparted their own unique influence to each story, highlighting the moral aspects and biblical stories they wished to emphasize. Much like the later “Fables of Aesop,” human and theological characteristics were attributed to both real and mythological animals in order to impart moral and social lessons.

Though physiologia delighted readers of all ages, these compendia were especially valuable as teaching tools for young children. Because of its versatility and whimsical, entertaining nature, the physiologus is thought to have been the widest-circulated form of literature, after the Bible, for most of the Middle Ages. Though common allegorical notions and lore for particular animals connect across each version, each physiologus is unique and often anonymously authored. Each scribe imparted their own unique influence to each story, highlighting the moral aspects and biblical stories they wished to emphasize. Much like the later “Fables of Aesop,” human and theological characteristics were attributed to both real and mythological animals in order to impart moral and social lessons.

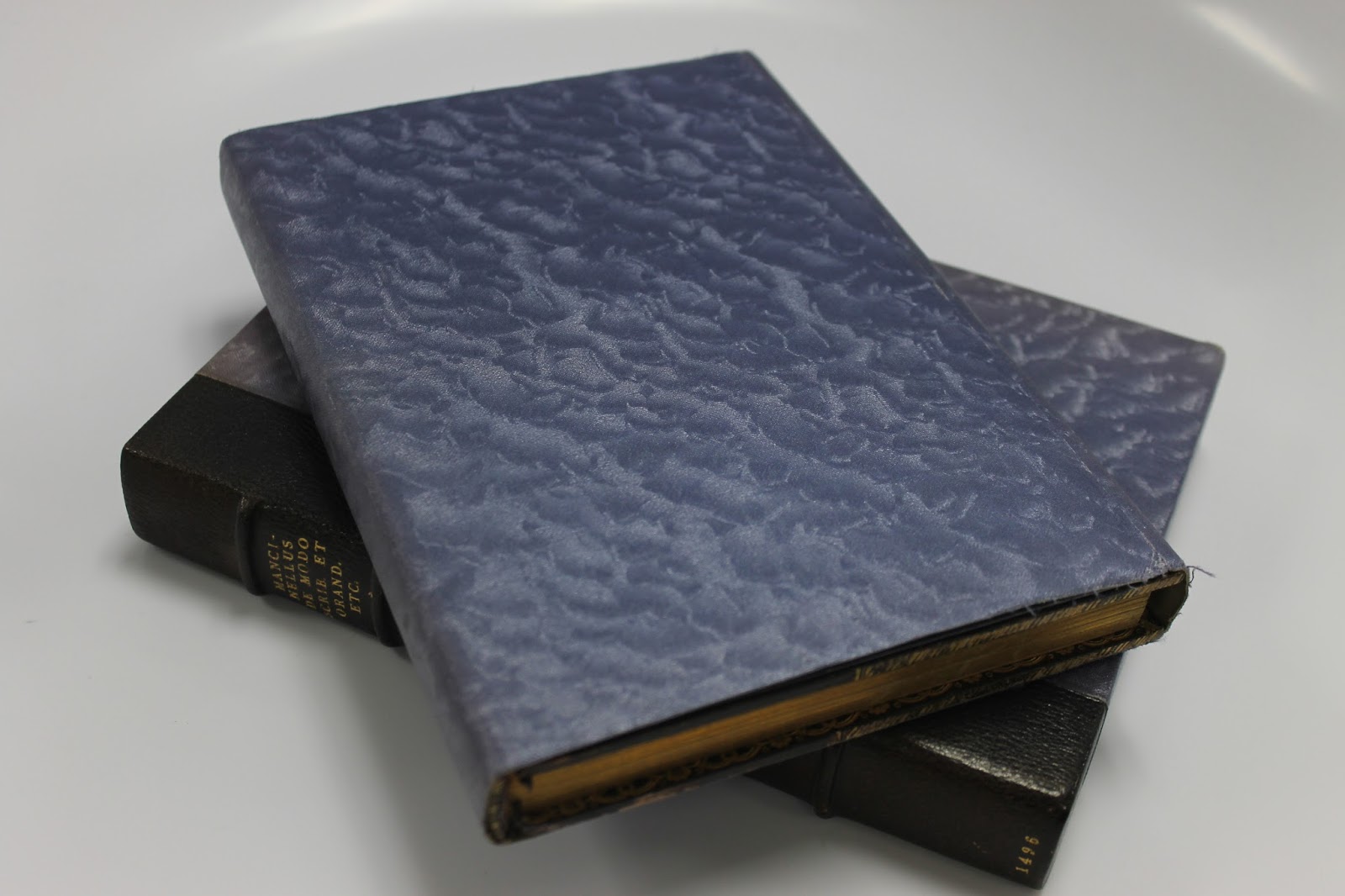

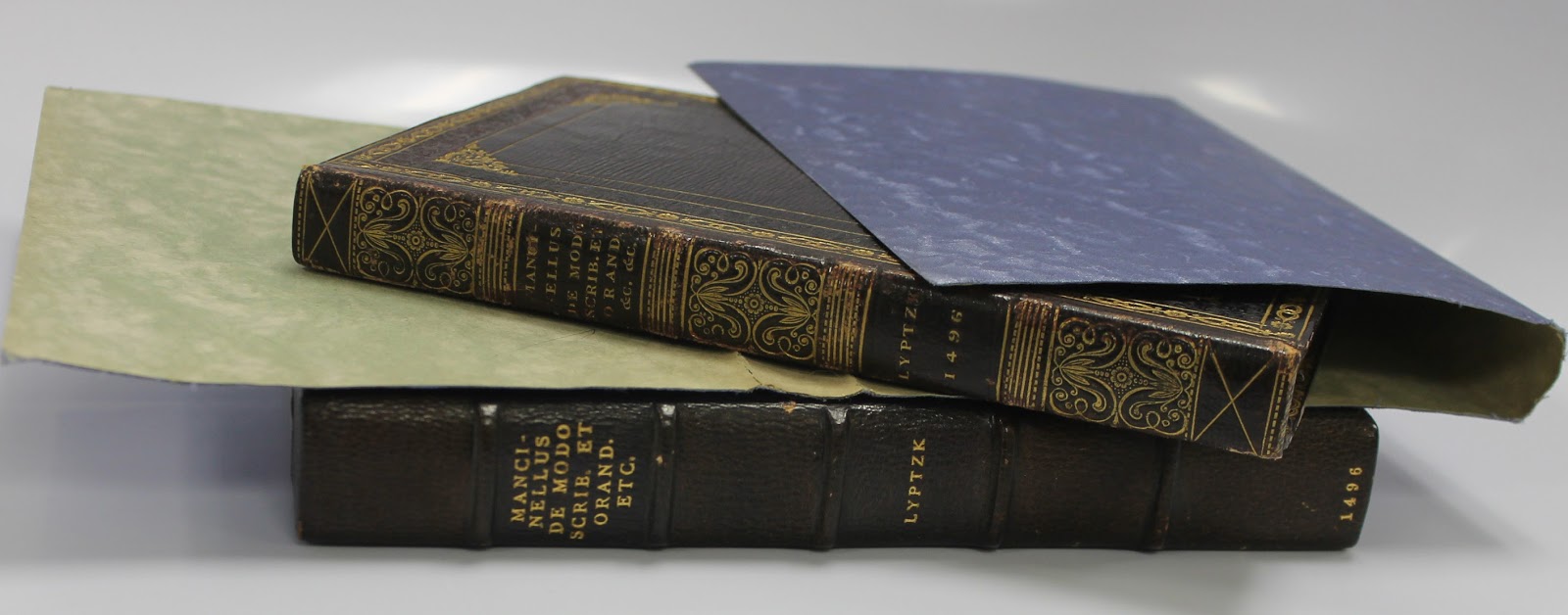

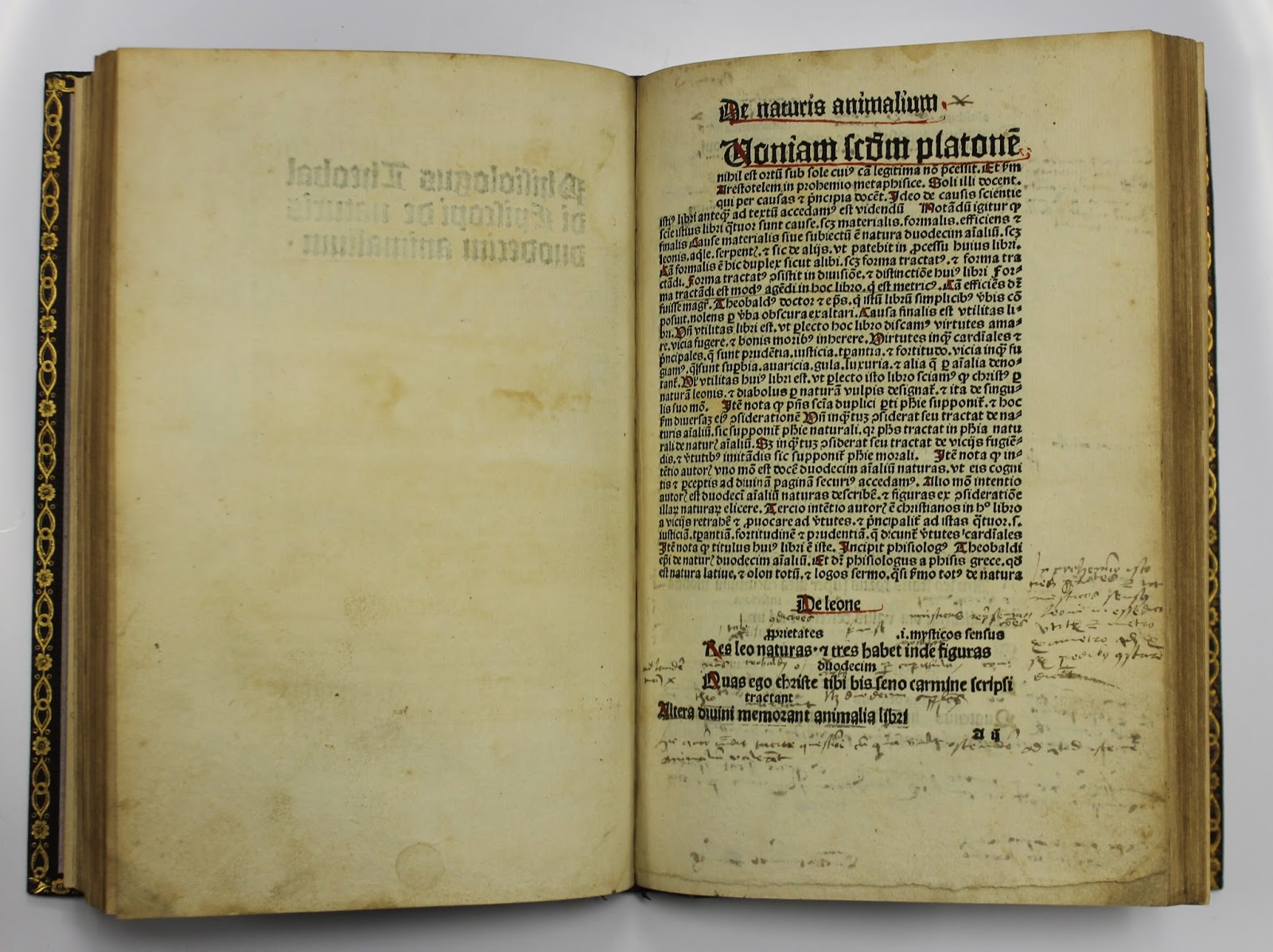

Excitingly, Brandeis University’s Archives and Special Collections holds a beautiful example of one such physiologus as part of its Incunabula collection*. Brandeis’ physiologus is a 1493 printing of a Latin manuscript attributed to Bishop Theobaldus, Abbot of Monte Cassino ca. 1022 to 1035. Fully titled “Phisiologus de Naturis Duodecim Animalum,” Theobaldus’ version contains the moral lessons of twelve animal entries: Lion, Eagle, Snake, Ant, Fox, Stag, Spider, Whale, Siren, Elephant, Turtle-dove and Panther. Though much smaller in number than other physiologia, the Theobaldus manuscript is unique in its metered form and inclusion of creatures typically left out of most versions of the genre.

Each entry contains two elements — a natural history of the animal and an application of allegory to what was described in the first part of the entry. The first contains an explanation of a selection of known or rumored behaviors and appearance of the animal, such as the Snake’s shedding of its skin or the coat pattern of the Panther. Other descriptions are slightly more fanciful:

Each entry contains two elements — a natural history of the animal and an application of allegory to what was described in the first part of the entry. The first contains an explanation of a selection of known or rumored behaviors and appearance of the animal, such as the Snake’s shedding of its skin or the coat pattern of the Panther. Other descriptions are slightly more fanciful:

“Stands in his might the Lion, on the highest peak of the mountain,

By whatsoever road he descends to the depth of the valley,

If through his sense of smell he perceives the approach of a hunter,

He rubs out with his tail, all the marks which his feet may have printed,

So that none most skilled can tell what road he has travelled,

Cubs, new born, live not till the sun three courses has finished,

Then with a roar the Lion arouses his cub from his slumbers,

When he begins to live, and gains all five of his senses,

Now whenever he sleeps his eyelids never are closed.”

These natural histories are then followed by an allegorical application of the animal’s described nature and characteristics into a moral lesson. As one could likely guess from the example, the lion, in the second component of its entry, will be explained as symbolic of the life of Christ, awakened by his father after “three slumbers.” Furthermore, the belief that a lion sleeps with eyes open is a reminder to Christians to be watchful of the second coming. Each entry is fascinating in the nuances of its theological allegories — the eagle as repentant and weary sinner, the ant as a wise worker who stores away its treasures and the whale as a symbol of false gods and prophets. The Spider is particularly interesting and important, as the Theobaldus physiologus contains the only known such occurrence of this animal in surviving manuscripts, as well as the Siren, which is not only mythological but typically anthropomorphic, and therefore not often included in lists of animals.

These natural histories are then followed by an allegorical application of the animal’s described nature and characteristics into a moral lesson. As one could likely guess from the example, the lion, in the second component of its entry, will be explained as symbolic of the life of Christ, awakened by his father after “three slumbers.” Furthermore, the belief that a lion sleeps with eyes open is a reminder to Christians to be watchful of the second coming. Each entry is fascinating in the nuances of its theological allegories — the eagle as repentant and weary sinner, the ant as a wise worker who stores away its treasures and the whale as a symbol of false gods and prophets. The Spider is particularly interesting and important, as the Theobaldus physiologus contains the only known such occurrence of this animal in surviving manuscripts, as well as the Siren, which is not only mythological but typically anthropomorphic, and therefore not often included in lists of animals.

Beyond the fable-esque qualities of the text, however, physiologia are valuable not only because of their colorful descriptions and literary qualities. Their existence, in addition to the unique structures and elements differing across each reiteration of the genre, reflect the philosophical and theological thought of the historical moment in which each version was created. Overall, these texts demonstrate the underlying doctrinal belief that since all of creation could be attributed to God, then of course elements of this creation — plants and animals — would be imbued with special messages and meanings. The ways in which this doctrine was applied in texts such as these, as well as the shifts in the animals chosen for each anthology and their particular aspects, allegories and characteristics, is a growing topic of research and inquiry.

As the physiologus form developed into the bestiary, scribes would begin to add bright illuminations and fantastical, though often unrecognizable, illustrations of the different animals. The allegories and connections of the animals would become ever more mythological and their descriptions and behaviors more fanciful. Each volume produced would alter the stories slightly more, and each author would add a small piece of themselves and their world into the texts. Yet their role as a source of whimsical moral instruction and a reflection of the beliefs of the age remained a constant in the ongoing evolution of study of the natural world.

As the physiologus form developed into the bestiary, scribes would begin to add bright illuminations and fantastical, though often unrecognizable, illustrations of the different animals. The allegories and connections of the animals would become ever more mythological and their descriptions and behaviors more fanciful. Each volume produced would alter the stories slightly more, and each author would add a small piece of themselves and their world into the texts. Yet their role as a source of whimsical moral instruction and a reflection of the beliefs of the age remained a constant in the ongoing evolution of study of the natural world.

*Icunabula (Latin for “cradles” or “swaddling clothes”) are materials (books, pamphlets, broadsides) printed (not handwritten) before 1501 (that is, they were printed in the first 50 years after the invention of the printing press).