Victor Young Collection

April 16, 2008

Description by Scott D. Paulin, Department of Music, Dartmouth College; photos and scans by Maggie McNeely

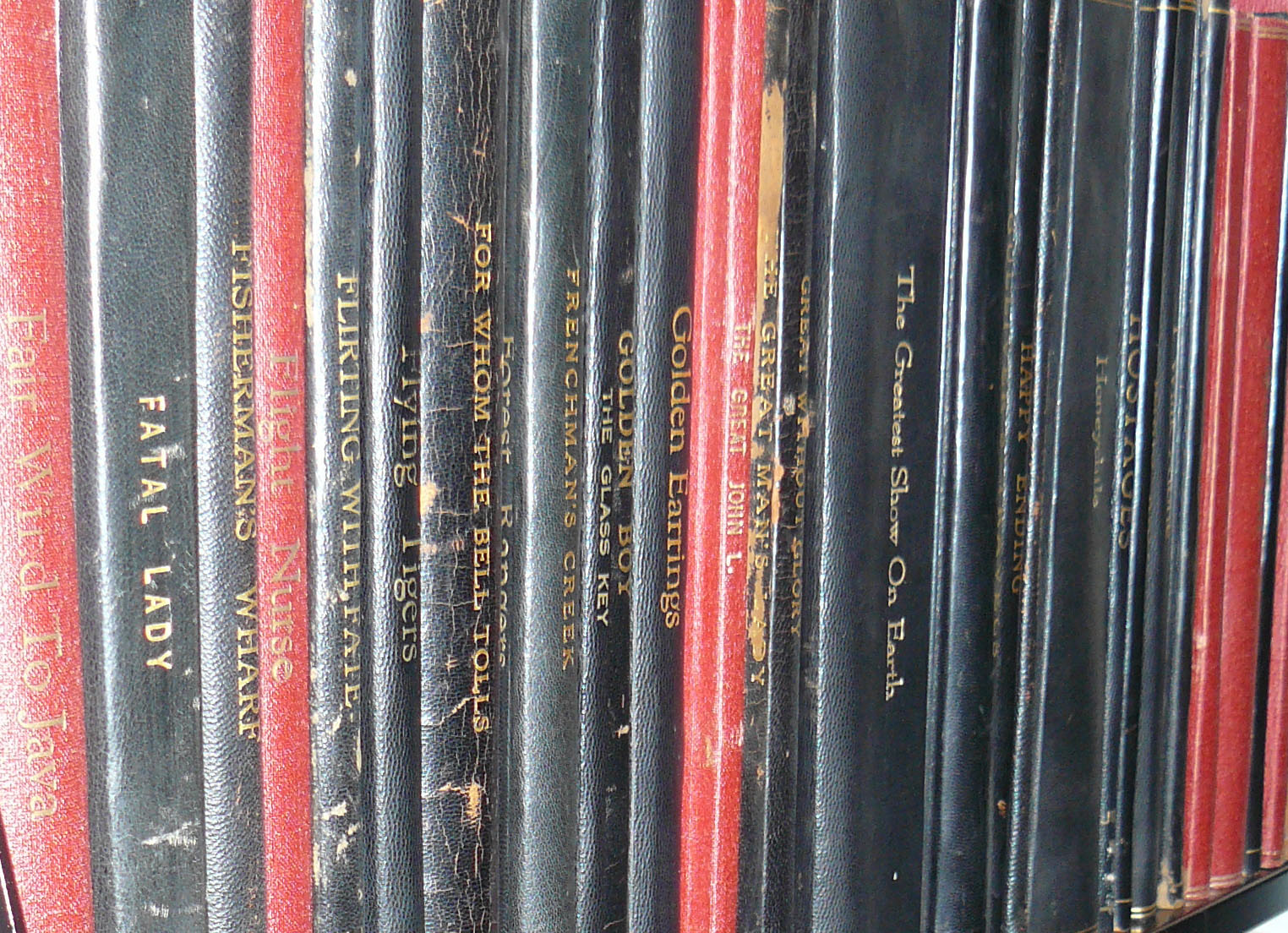

The Victor Young Collection at Brandeis includes more than 100 musical scores and LP recordings as well as awards (including an Oscar and Golden Globe), clippings, photographs and memorabilia. Donated to Brandeis by Young’s family, the collection is frequently used by musicologists and other researchers. Victor Young (1900–1956) was an American composer, arranger, conductor and violinist who wrote and directed music for many Hollywood motion pictures in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Born in Chicago, Young lived for much of his childhood in Poland, where he studied violin; in 1917 he became a violinist with the Warsaw Philharmonic before returning to the United States and embarking on his career as a music director and composer.

The Victor Young Collection at Brandeis includes more than 100 musical scores and LP recordings as well as awards (including an Oscar and Golden Globe), clippings, photographs and memorabilia. Donated to Brandeis by Young’s family, the collection is frequently used by musicologists and other researchers. Victor Young (1900–1956) was an American composer, arranger, conductor and violinist who wrote and directed music for many Hollywood motion pictures in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Born in Chicago, Young lived for much of his childhood in Poland, where he studied violin; in 1917 he became a violinist with the Warsaw Philharmonic before returning to the United States and embarking on his career as a music director and composer.

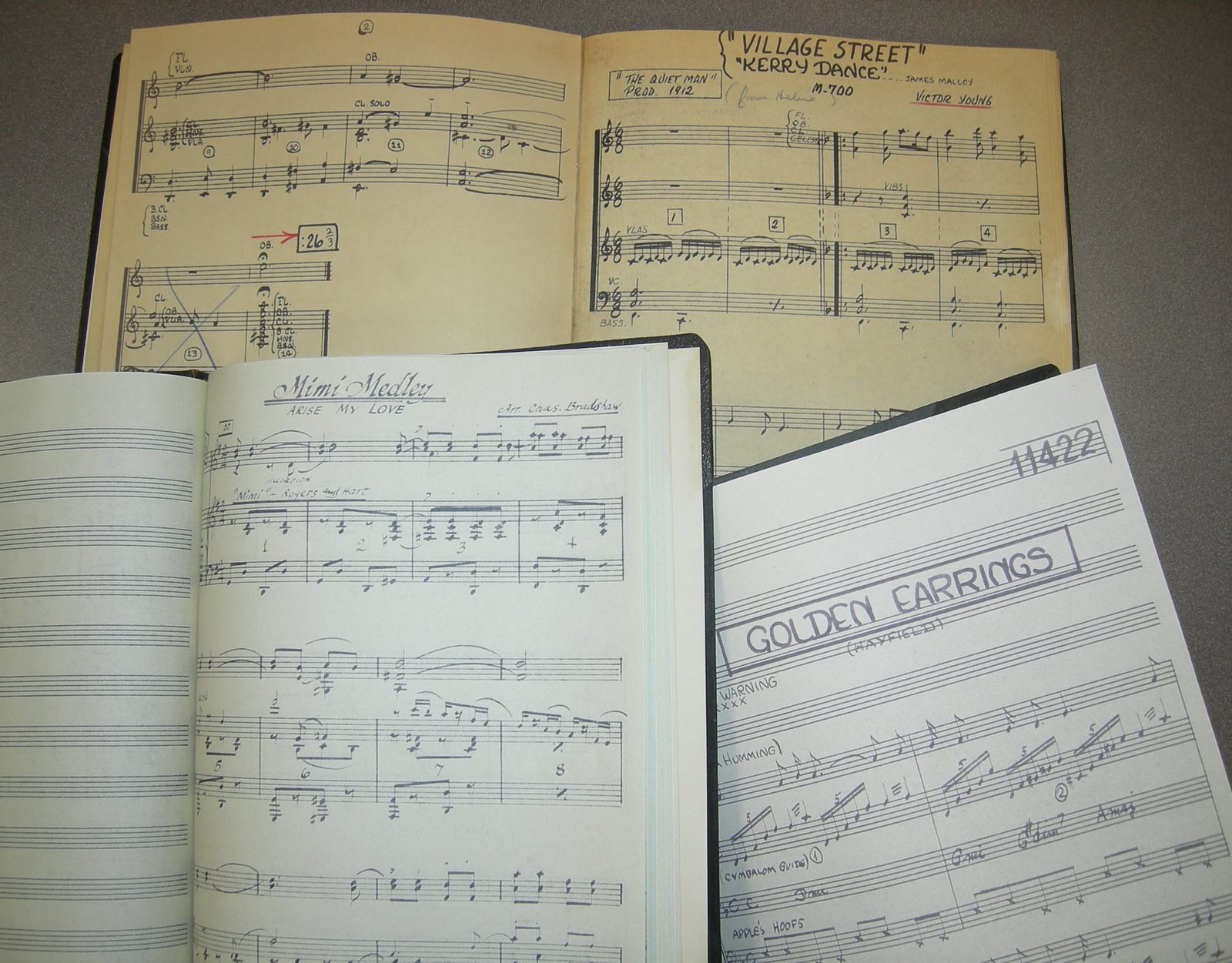

Having worked in the 1920s as a vaudeville violinist, a theatre concertmaster and the assistant musical director for the Chicago-based Balaban and Katz theatres—where he arranged music for silent film accompaniment—Young was displaced temporarily by the coming of sound film into radio and recording work. In 1935 he was wooed to Hollywood by Paramount Pictures, most likely on the basis of his work at the Balaban and Katz chain, which the studio owned. For the rest of Young’s life he wrote and directed music at Paramount, including scores for “Love Letters,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” “Shane,” and many films by key Paramount directors such as Cecil B. DeMille, Preston Sturges and Mitchell Leisen. However, several of the best-remembered films in Young’s filmography were produced elsewhere, as the composer also worked at Columbia (“Golden Boy”), Republic (“Johnny Guitar”), and director-producer John Ford’s independent Argosy Pictures (“The Quiet Man,” “Rio Grande”), among others. Along the way he racked up 22 Academy Award nominations — four each in 1940 and 1941 — before finally winning a posthumous Oscar for Paramount’s “Around the World in 80 Day”s in 1956.

Having worked in the 1920s as a vaudeville violinist, a theatre concertmaster and the assistant musical director for the Chicago-based Balaban and Katz theatres—where he arranged music for silent film accompaniment—Young was displaced temporarily by the coming of sound film into radio and recording work. In 1935 he was wooed to Hollywood by Paramount Pictures, most likely on the basis of his work at the Balaban and Katz chain, which the studio owned. For the rest of Young’s life he wrote and directed music at Paramount, including scores for “Love Letters,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” “Shane,” and many films by key Paramount directors such as Cecil B. DeMille, Preston Sturges and Mitchell Leisen. However, several of the best-remembered films in Young’s filmography were produced elsewhere, as the composer also worked at Columbia (“Golden Boy”), Republic (“Johnny Guitar”), and director-producer John Ford’s independent Argosy Pictures (“The Quiet Man,” “Rio Grande”), among others. Along the way he racked up 22 Academy Award nominations — four each in 1940 and 1941 — before finally winning a posthumous Oscar for Paramount’s “Around the World in 80 Day”s in 1956.

Critics and scholars have long noted that Young’s compositions are distinguished especially by a gift for melody, and indeed, his scores often produced hit songs, such as “Stella by Starlight,” a theme originally from “The Uninvited.” This skill proved to be a marketing bonanza for Paramount, as when Peggy Lee’s recording of the title song from “Golden Earrings” became a jukebox standard, advertising the film well in advance of its theatrical release. But in certain ways, Young’s reputation for straightforward tunefulness worked against him; had his scores been less easy on the ears, he might have more readily attracted serious attention in a critical climate that often holds sentimentality under suspicion. Even a fellow Hollywood composer, Miklós Rózsa, could refer to Young’s “Broadway-cum-Rachmaninoff idiom” with implicit scorn, contrasting this “accepted style” with the bolder experiments he saw himself pursuing.[1]

Critics and scholars have long noted that Young’s compositions are distinguished especially by a gift for melody, and indeed, his scores often produced hit songs, such as “Stella by Starlight,” a theme originally from “The Uninvited.” This skill proved to be a marketing bonanza for Paramount, as when Peggy Lee’s recording of the title song from “Golden Earrings” became a jukebox standard, advertising the film well in advance of its theatrical release. But in certain ways, Young’s reputation for straightforward tunefulness worked against him; had his scores been less easy on the ears, he might have more readily attracted serious attention in a critical climate that often holds sentimentality under suspicion. Even a fellow Hollywood composer, Miklós Rózsa, could refer to Young’s “Broadway-cum-Rachmaninoff idiom” with implicit scorn, contrasting this “accepted style” with the bolder experiments he saw himself pursuing.[1]

In the most extended critical discussion of Young to date, William Darby and Jack Du Bois identify the composer’s other distinguishing trait as “adaptability.”[2] Indeed, his genre-spanning filmography reveals a striking chameleonic skill, as do his impersonations of national and ethnic idioms: Irish in “The Quiet Man,” Spanish in “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” “Gypsy” in “Golden Earrings,” countless others in the Oscar-winning “Around the World in Eighty Days,” which must have been a dream project for Young for this very reason. While versatility of style (along with speed) was one of the basic job qualifications for a studio composer, Young seemed to submerge his personality more thoroughly than others. (The authorial fingerprints of a Korngold, Herrmann or even a Steiner score are bold by comparison to Young’s.) Yet this is part of what made him an exemplary studio-system composer of the classical Hollywood era, and what makes him a crucial figure still for film-music studies: his mastery of the system’s demand for effective yet unobtrusive music to give a final polish to its products. A quotation in a 1955 Chicago Sun-Times article sums up Young’s musical aims in terms that also neatly convey something of the man’s uninhibited personality:

In the most extended critical discussion of Young to date, William Darby and Jack Du Bois identify the composer’s other distinguishing trait as “adaptability.”[2] Indeed, his genre-spanning filmography reveals a striking chameleonic skill, as do his impersonations of national and ethnic idioms: Irish in “The Quiet Man,” Spanish in “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” “Gypsy” in “Golden Earrings,” countless others in the Oscar-winning “Around the World in Eighty Days,” which must have been a dream project for Young for this very reason. While versatility of style (along with speed) was one of the basic job qualifications for a studio composer, Young seemed to submerge his personality more thoroughly than others. (The authorial fingerprints of a Korngold, Herrmann or even a Steiner score are bold by comparison to Young’s.) Yet this is part of what made him an exemplary studio-system composer of the classical Hollywood era, and what makes him a crucial figure still for film-music studies: his mastery of the system’s demand for effective yet unobtrusive music to give a final polish to its products. A quotation in a 1955 Chicago Sun-Times article sums up Young’s musical aims in terms that also neatly convey something of the man’s uninhibited personality:

“Writing a movie score is like a boy sitting in a balcony with a girl: He must be forceful enough to impress the girl — but not loud enough to attract the usher!”

Other Literature on Victor Young

-

Kathryn Kalinak, “How the West was Sung: Music in the Westerns of John Ford” (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007).

-

Scott D. Paulin, “Piercing Wagner: The Ring in Golden Earrings,” in Wagner and Cinema, ed. Jeongwon Joe and Sander Gilman (Indiana University Press, forthcoming).

-

W. Anthony Sheppard, “An Exotic Enemy: Anti-Japanese Musical Propaganda in World War II Hollywood,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 54 (2001): 303-357.

Footnotes

- Miklós Rózsa quoted in Royal S. Brown, Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994), 96. Young “worked at a time and for a studio where nothing experimental or outlandish was wanted or even tolerated.” Tony Thomas, Music for the Movies, 2nd ed. (Los Angeles: Silman-James Press, 1997), 50-55.

- William Darby and Jack Du Bois, American Film Music: Major Composers, Techniques, Trends, 1915–1990 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1990), 267-302.