Voices of Wartime collection (1940-1951)

December 12, 2025

Description by Alejandro Franqui-Ferrer, University Archives and Special Collections intern.

The diaries, letters, and collected scraps which are the Voices of Wartime Collection, now held at Brandeis University’s Robert D. Farber Archives and Special Collections, offer the researcher a look into the lives of four individuals during the Second World War. The collection is made up of four distinct parts, each produced by different authors. These are a diary written in a notebook, likely produced by a middle-aged woman in 1940-41; a diary-scrapbook written in and compiled by a Navy Ordnanceman from 1941-1951; four diaries written by a Welshman in the RAF from 1941-1946; and approximately 150 letters written by a communications officer serving in the Pacific theatre to his wife, which date from 1942-1945. Each piece is fascinating for its unique micro-perspectives on the larger events of the war one may be quite familiar with.

Notebook Diary

The notebook diary1 (1940-41) was written by an unknown author from Eastern Pennsylvania, although there are some things we can deduce about them. Firstly, the author seems to be middle-aged or older, as they mention seeing the 1893 World’s Fair. The author is perhaps also upper middle class, which one can surmise from descriptions of multiple trips by car which appear to be for pleasure (note that the United States was still in the depression in 1940). Finally, the author is perhaps a woman, which can be guessed from the fact that most names they mention are women’s names, and the recurring mentions of two men, Chester and Clarence, who accompany the author on trips seeming to refer to the author’s husband and old family friend. There is also a printed slip within the notebook which reads, “Mrs. L.B. Prowell 314 Howard Ave. Altoona Pa. Levi’s widow Louis Winifred”. Is the author Mrs. L.B. Prowell? It seems possible but we cannot be sure without further research.

The diary consists of largely personal retellings of the author’s travels, updates on the the health and wellbeing of the author’s friends and acquaintances, notes on passages from the Bible and sermons from the author’s reverend, and the author’s thoughts on the development of the war, which they presumably learn of through the newspaper or word of mouth. This last category seems to be the most interesting as the United States has not yet engaged in the war, and in the minds of Americans still exists as something far off. Early in the diary, on Tuesday April 16, 1940, the author writes, “War raging in Scandinavia. Hitler seems to be gaining ground though losing at sea. Only God knows the outcome.” Apparently the author had just heard of Operation Weserübung (which began April 10), the German invasions of Denmark and Norway, and the Battles of Narvik, during which the British had defeated the Germans in some naval skirmishes. By May 1, the author writes “Norway falls under Hitler’s ‘juggernaut’. God deliver Norway’s great people and noble King Haakon VII.”

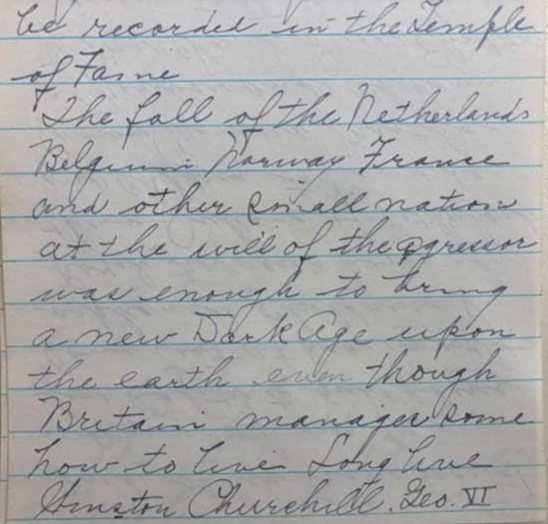

Because this diary was written in the early days of the war, most war news reported has the Axis powers seeming victorious, which allows us a look into the author’s disdain for them. One passage reads,

The fall of the Netherlands Belgium Norway France and other small nations at the will of the aggressor was enough to bring a new Dark Age upon the earth even though Britain manages somehow to live. Long live Winston Churchill, Geo. VI and other brave hearts!

These passages, in conjunction with the religious ruminations and records of the author’s travels with her family and friends make it easy to imagine oneself in the author’s headspace during this turbulent time for the world.

Diary-Scrapbook

The diary-scrapbook2 (1941-51) was written by John Harlan Jason (born 1922). Jason served the U.S. Navy from September 1, 1942, to November 4, 1946, during which he was a U.S. Ordnanceman in the Atlantic theatre of the war. Jason’s “diary-scrapbook” is exactly what it sounds like - a book sold to Navy men which had built in sections for daily written entries and sections to tape in scrap materials. Jason made use of both sections, but more often than not, Jason would skip taping and instead slide loose materials within the pages of the book. Much of the content of this piece comes from these loose materials, which are made up of official Navy documents, identification cards, and newspaper clippings.

The book begins with Jason in California, having just been admitted into the Navy. Many early entries consist of short notes detailing the crux of a day: “[September] 10. Stood guard, marched all day. [September] 11 - Marched + went to show.” In November and December of 1942, Jason writes down his scores for his Ordnanceman’s tests, “20mm cannon 94% … Bombs & Fuses 99% …”, and among the scraps in the book we can find his Certificate of Aviation Ordnancemen’s School Completion, which was awarded the next year on January 16, 1943.

With Jason becoming an Ordnanceman soon into the diary, one comes to see later that the entire book covers a rather formative period in the soldier’s life. On June 30 of the same year, Jason reports his marriage to Martha Barbee (who he calls Marty) at Church of Christ, and their subsequent trips in their Buick. Skipping many days after this point, we catch up with Jason for a couple notes about seeing his family throughout October and November before Jason goes to Norfolk Virginia and boards a Convoy to Casablanca in December. He writes, “Missed Christmas again without the folks and my wife.” On duty now and apparently stationed in Norfolk, the diary slows down and eventually comes to a halt, but not before we learn that Jason received a Second Class Petty Officer Rating on February 2, 1944, and that he has travelled to New York City; Recife, Brazil; Capetown, South Africa; Diego-Suarez (now Antsiranana), Madagascar; Karachi, India (now Pakistan); Boston, and other places.

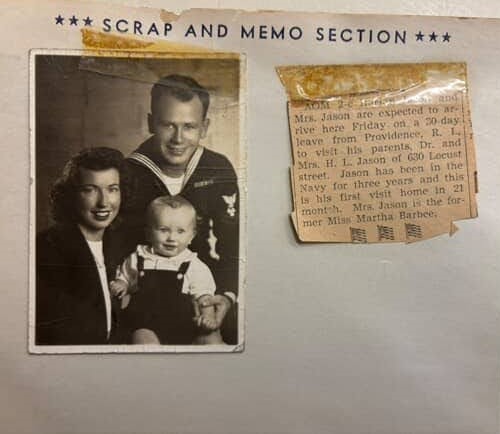

Jason’s entries and scraps make for an exciting read which make the war seem more like an adventure than a conflict, although this may be a result of his apparent lack of ever seeing combat, or at least his lack of reporting it. We know that Jason seems to have been aware of the danger posed by the war, as many of the scraps he collects are stories on deadly naval disasters (e.g. “Thousands of Boys Faced Sea Death, Three Destroyers Sank in Storm on Pacific Costing Lives of 700”).  Perhaps one of the most interesting parts of this piece are the scraps Jason collects, as they provide a rather unobstructed view into what he cares about. Among newspaper clippings reporting on disasters, Jason also collected pictures of new Naval technologies, printed Jokes about Navy life, and some photographs. The final photograph shows Jason with his wife and a child, presumably taken sometime in the late ‘40s or early ‘50s, since he looks older than in his earlier photographs, and because a child doesn’t seem to be mentioned earlier in the diary.

Perhaps one of the most interesting parts of this piece are the scraps Jason collects, as they provide a rather unobstructed view into what he cares about. Among newspaper clippings reporting on disasters, Jason also collected pictures of new Naval technologies, printed Jokes about Navy life, and some photographs. The final photograph shows Jason with his wife and a child, presumably taken sometime in the late ‘40s or early ‘50s, since he looks older than in his earlier photographs, and because a child doesn’t seem to be mentioned earlier in the diary.

Four Diaries from a Man in the RAF

The four diaries3 (1943-46) written by a Welshman in the RAF were produced by Stanley Taylor, a man from Old Colwyn, North Wales. Taylor does not mention much about his personal life apart from his home and the people he corresponds with, which makes it difficult to have a general understanding of his life, but nonetheless what he provides for us in his four (mini) diaries is quite interesting.

Taylor’s diary entries are written quite concisely. Most days Taylor only has a sentence or two to report. The first diary opens in January of 1943, and the types of things Taylor likes to jot down are immediately evident. Firstly, Taylor records whenever he sends or receives any form of correspondence, whether they be letters or airgraphs (a type of microfilmed letter used by Britain during the war), to any of his family and friends back home. The first dated entry is simply “Sent airgraphs to Cecil & Frank.” (Sunday, Jan 3, 1943). Secondly, Taylor makes sure to write down seemingly every movie and show he sees. The next day’s entry reads, “Saw Station Panto - ‘Cinderella’”. Thirdly, many of Taylor’s entries are what appear to be technical notes, which is why it is likely Taylor served as an air technician. Two entries after the one last discussed, we read “Black Blen - mun wh - not charging gen. Changed on T (inch)”. This entry is difficult to understand but seems to be a note by Taylor to remind himself that a Black Blenheim aircraft was suffering from a faulty generator that would not charge, which was subsequently changed on Tuesday. Much of the diaries are made up of these three types of entries, but there are also many other fascinating notes.

![Handwritten entry from 7 Wed, reading in part "another [swastika] down, total 18."](images/2025/vow3.jpg) For example, Taylor was in the habit of tallying how many German planes his squadron had shot down. On March 19, 1943, it was 17 down. By June 26, the total had increased to “55 down, 2 prob, & 4 damaged.” Taylor either refers to the Germans as “gerries”, “huns”, or sometimes he simply draws a swastika, adding a layer of personality to the entries.

For example, Taylor was in the habit of tallying how many German planes his squadron had shot down. On March 19, 1943, it was 17 down. By June 26, the total had increased to “55 down, 2 prob, & 4 damaged.” Taylor either refers to the Germans as “gerries”, “huns”, or sometimes he simply draws a swastika, adding a layer of personality to the entries.

Taylor was likely in the 153 Squadron of the RAF or at least worked around them extensively (as evidenced by his writing “Typical 153!!!” after a Squadron-wide mistake), and so he traveled to many places during the war. The first diary likely begins on an airbase in Northern Ireland, after which Taylor writes down “Leaving Bally-H!” on February 23, likely referring to one of the many places in the region beginning with the word “Bally”. Afterwards, it seems Taylor was stationed in Rhegaia, Algiers, around the summer of 1943, then Alma Marino, Italy in March, 1944, then Taranto, Italy on September 19, and other parts of Italy afterwards. All the while Taylor continues to make technical notes, tally German planes taken down, and noting when he goes into town to see a movie with his friends. These friends’ names are Joe, Adam, Evie, and others.

Taylor also makes some notes about current events, “Good War news these days, Russians going into Berlin, Bologna falls”, and he even spots Winston Churchill twice (in the summer of 1943)! But still, Taylor’s diaries provide a deeper look more into the actual service and work that went into being in the RAF and less into bigger picture events like are discussed by other authors in the collection. As such, the diaries come off as more grounded and detail oriented.

The Communication Officer’s Letters

The ~150 letters in this collection were written by Lieutenant Armand Minkin4, who was born on January 25, 1911, in Fall River, Massachusetts. He graduated from BMC Durfee High School in 1928, and graduated from Boston University in 1932.5 Minkin’s early birth would make him 30 years old when the United States joined WWII, which is one explanation as to why he was able to achieve such a high rank. Minkin served in the Pacific theatre of the war as a Communications Officer, which entailed the managing of safe information transfer between units. Minkin was married in March 1942, and he seems to have had only one child – a son named Leonard R. Minkin. This son was born before the creation of these letters, and Minkin frequently mentions him.

All of the letters in the collection have been written for Minkin’s wife, who at the time lived in Newport, Rhode Island, while Armand writes from San Francisco. All of the materials date between April 1944 and August 1945, except for one envelope without a letter from December of 1942. Many of these letters are written on sequential days, giving the impression of a constant conversation between the husband and wife, especially if the collection is missing some letters.

Much of what Minkin writes to his wife consists of loving messages which serve as an interesting look into the romance of this period. The first sentence the researcher will encounter upon reading the letters is “Dearest darling - It seems only a few minutes ago that I called you and the 8 minutes that we talked seem like 8 seconds now that it’s over.” These messages usually make up the first and last chunks of each letter. The rest consists of inquiries into his wife’s life on the homefront, personal anecdotes, and some ruminations on the events of the war. Minkin comments on and asks for more details on the personal problems she has, which she seems to have told him about through letters sent to him which we do not have. Minkin also seems to refrain from telling any stories about his work which are concerning, as most of what he retells centers around social interactions between him and other servicemen. It also is likely that Minkin never saw combat, and was instead stationed on the mainland for most of the war.

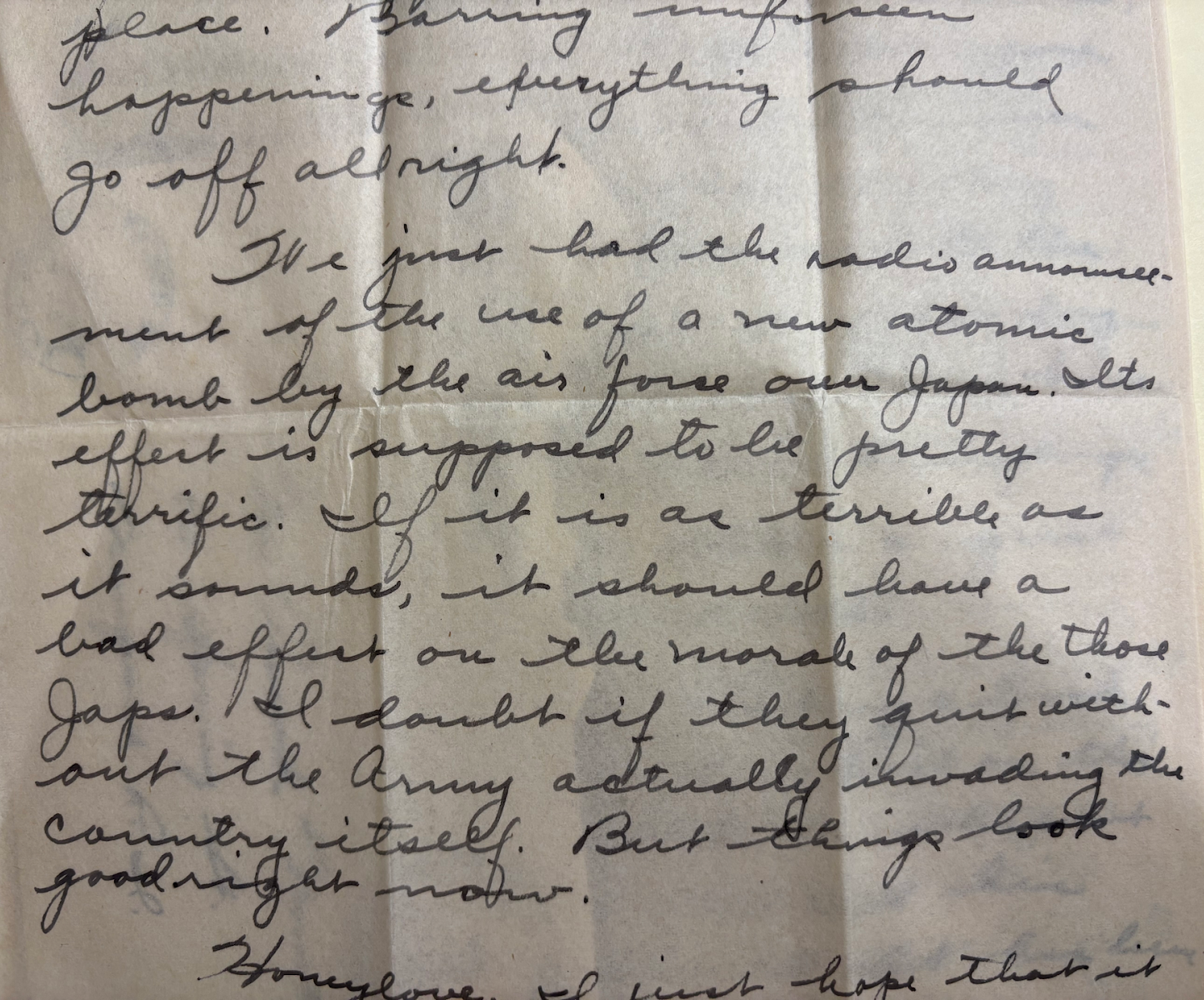

Minkin does not refrain from commenting on the larger events of the war, including the internment camps and Roosevelt’s death, once again providing a very contextually grounded way of seeing the events we are so familiar with. For example, on August 7, 1945, Minkin writes,

I’ve just heard the radio announcement of the use of a new atomic bomb by the air force over Japan. Its effect is supposed to be pretty terrific. If it is as terrible as it sounds, it should have a bad effect on the morale of those Japs. I doubt if they quit without the army actually invading the country itself. But things look good right now.

The overall effect of Minkin’s letters is to leave the researcher with a good impression of what it was like to be an older and more mature family man during this time, a view that the other two younger soldiers in the collection do not provide. While the other soldiers focus more on where they travel, tallying downed planes or collecting pictures of planes and ships, Minkin seems more focused on the interactions he has with others and the lives of his wife and “dumpling”. As such, the letters are useful for the uniqueness of their mature tone when compared to other letters written by soldiers serving in the war.

In total, the Voices of Wartime collection offers a most intimate view into the lives of four individuals concurrent with the events we have read so much about. Each piece provides insight into the grounded points of view by which the larger events of the world were experienced, and as such, offer the researcher details about the day-to-day and thought life of average people during this time.

Footnotes

- Voices of Wartime collection, Notebook diary.

- Voices of Wartime collection, John Harlan Jason diary, clippings, and personal documents.

- Voices of Wartime collection, Stanley Taylor diaries.

- Voices of Wartime collection, Armand Minkin letters.

- Armand Minkin obituary