Diary of a World War I Aid Worker

July 28, 2010

Description by Karen Adler Abramson, Associate Director for University Archives and Special Collections

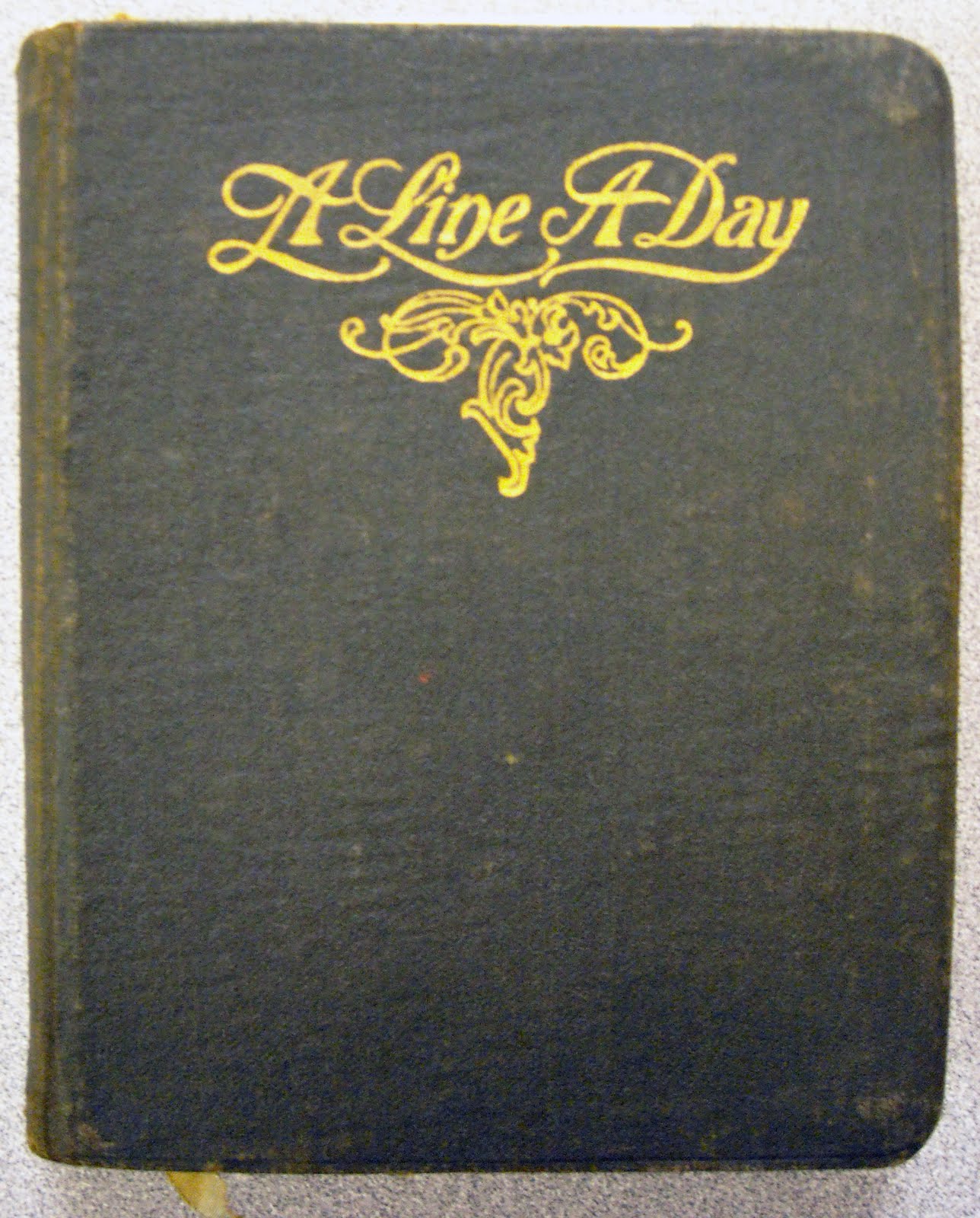

The Brandeis University Special Collections contains a number of materials documenting 20th-century European conflicts, including the two world wars. Most recently, the department acquired the diary of an American Red Cross worker (Anna Weimar, b. 1869) who was stationed at the U.S. Navy base in Nantes, France, during the final months of World War I. Weimar's diary spans a full year (June 28, 1918 to July 7, 1919) and ends just eight days after the establishment of the League of Nations.

The Brandeis University Special Collections contains a number of materials documenting 20th-century European conflicts, including the two world wars. Most recently, the department acquired the diary of an American Red Cross worker (Anna Weimar, b. 1869) who was stationed at the U.S. Navy base in Nantes, France, during the final months of World War I. Weimar's diary spans a full year (June 28, 1918 to July 7, 1919) and ends just eight days after the establishment of the League of Nations.

A volunteer worker with the American Red Cross in Chicago, Weimar was 49 years old when she sailed to Europe in the summer of 1918. Though her duties were primarily clerical in nature, Weimar spent much of her time tending to patients at the naval hospital in Nantes: writing letters for them, bringing treats and even placing flowers at their grave sites when they died. One senses the emotional upheaval of her work and the sadness that pervades many entries. Weimar is also candid about the gruesomeness of the war. In one entry from October 12, 1918, she writes:

Today I saw the worst case I've seen thus far a very nice blond boy had his whole chin, a piece of his tongue, his right cheek – and just as the shrapnel struck him he was in the act of pulling his helmet down & it took off his right thumb – he can only take liquids his front teeth & lower jaw being gone – he tried to tell me he wanted some coca – the kind you pour hot water on & drink – he can't get enough to eat. I told him Id [sic] have some for him in 15 minutes – in ten minutes I was back with a pound can full – a lb of chocolate and a jar of malted milk – I just asked one nurse after another until I found one who had it – and I got it – I'll see that he has plenty to eat of cocoa & chocolate –

In another entry from Nov. 6, 1918—five days before the Armistice—Weimar writes the following:

I feel half sick today and have the blues a lot of boys came in today in the rain & they had to be put into those cold, bare wards – they had had no food for 24 hrs & were almost overlooked – one is desperately sick with pneumonia & they cant find Hicks to look after him – it has poured rain for two days & nights. The place is a mud hole – & all the pneumonias are worse – they had the delirious Greek with poor Anderson who was afraid of him – then they moved Anderson out of the little room & put the bad pneumonia case in with the Greek – I wish it would stop raining – McCready can hardly get his breath. at 9:30 I made some hot chocolate in my room for Kathleen & French – its [sic] against all rules to have a man come into our rooms but I did it anyway – he is a convalescent patient & looked as tho’ he would have a chill—they were both drenched – the Swedes all cackled –

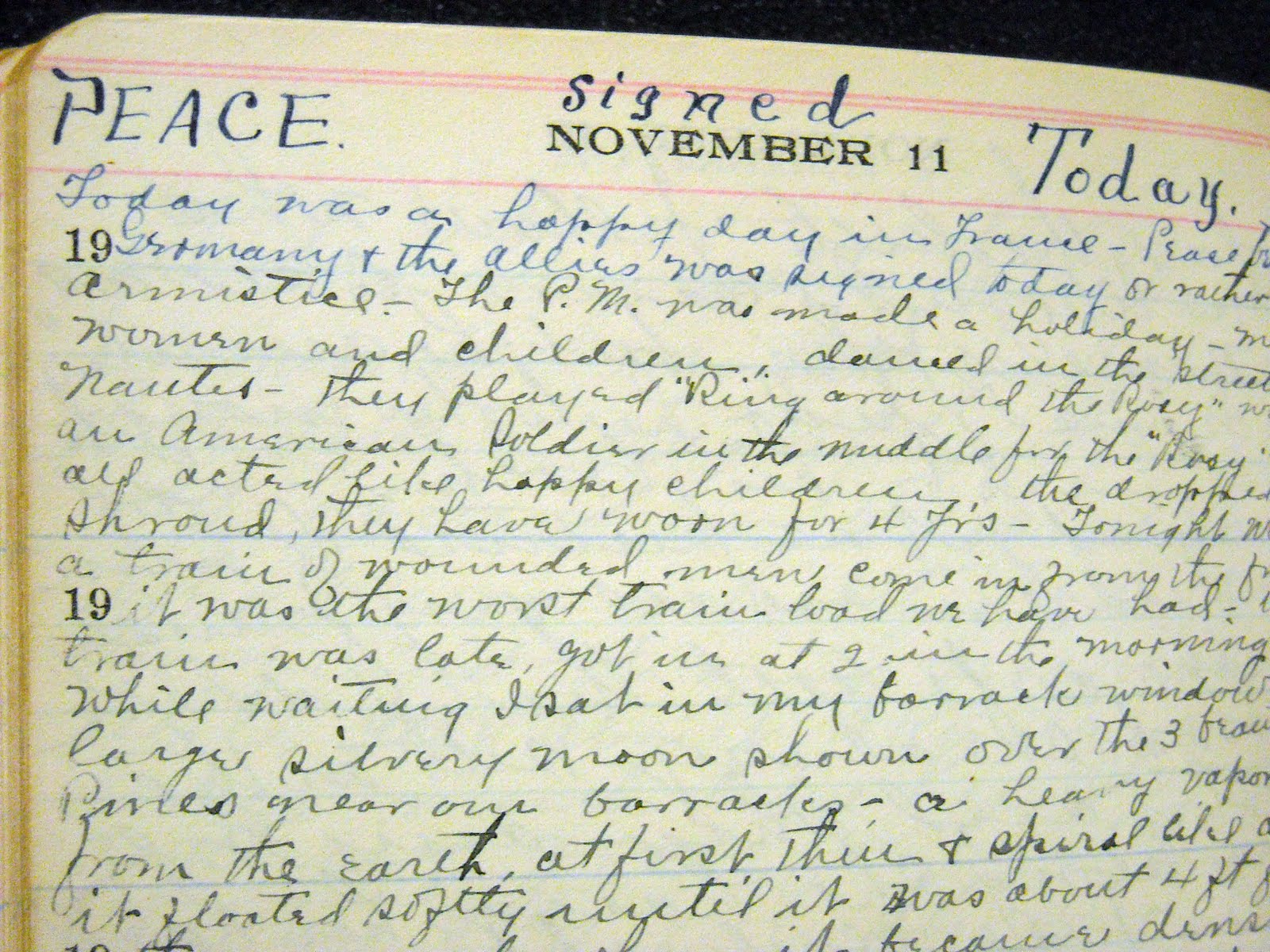

There are moments of levity in Weimar's diary, though they, too, are sometimes punctuated by heaviness. In her entry for Nov. 11, 1918, Weimer writes in bold at the top of the page: "PEACE signed Today." She goes on to say:

Today was a happy day in France – Peace between Germany & the allies was signed today or rather an Armistice – The P.M. was made a holiday – men, women and children danced in the streets of Nantes – they played "Ring around the rosy" with an American soldier in the middle for the "Rosy" They all acted like happy children, the[y] dropped the shroud they have worn for 4 yrs Tonight we had a train of wounded men come in from the front. It was the worst train load we have had – the train was late, got in at 2 in the morning – While waiting I sat in my barrack window – a large silvery moon shown over the 3 beautiful pines near our barracks – a heavy vapor rose from the earth, at first thin & spiral like and it floated softly until it was about 4 ft from the ground, when it became denser & moved from side to side – I imagined it was the spirits of our boys who had played "Hookey" [sic] from heaven to celebrate the good news –

Today was a happy day in France – Peace between Germany & the allies was signed today or rather an Armistice – The P.M. was made a holiday – men, women and children danced in the streets of Nantes – they played "Ring around the rosy" with an American soldier in the middle for the "Rosy" They all acted like happy children, the[y] dropped the shroud they have worn for 4 yrs Tonight we had a train of wounded men come in from the front. It was the worst train load we have had – the train was late, got in at 2 in the morning – While waiting I sat in my barrack window – a large silvery moon shown over the 3 beautiful pines near our barracks – a heavy vapor rose from the earth, at first thin & spiral like and it floated softly until it was about 4 ft from the ground, when it became denser & moved from side to side – I imagined it was the spirits of our boys who had played "Hookey" [sic] from heaven to celebrate the good news –

Weimar was stationed in Europe for another seven months following the Armistice, and her journal is filled with descriptions of her travels and her impressions as a tourist. Her diary, which has found a permanent home at Brandeis, is a valuable first-person account of life as an aide and hospital worker in the European theater during the final phase of World War I.