WWII Guernsey Scrapbook

June 1, 2012

Description by Anne Marie Reardon, Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in history

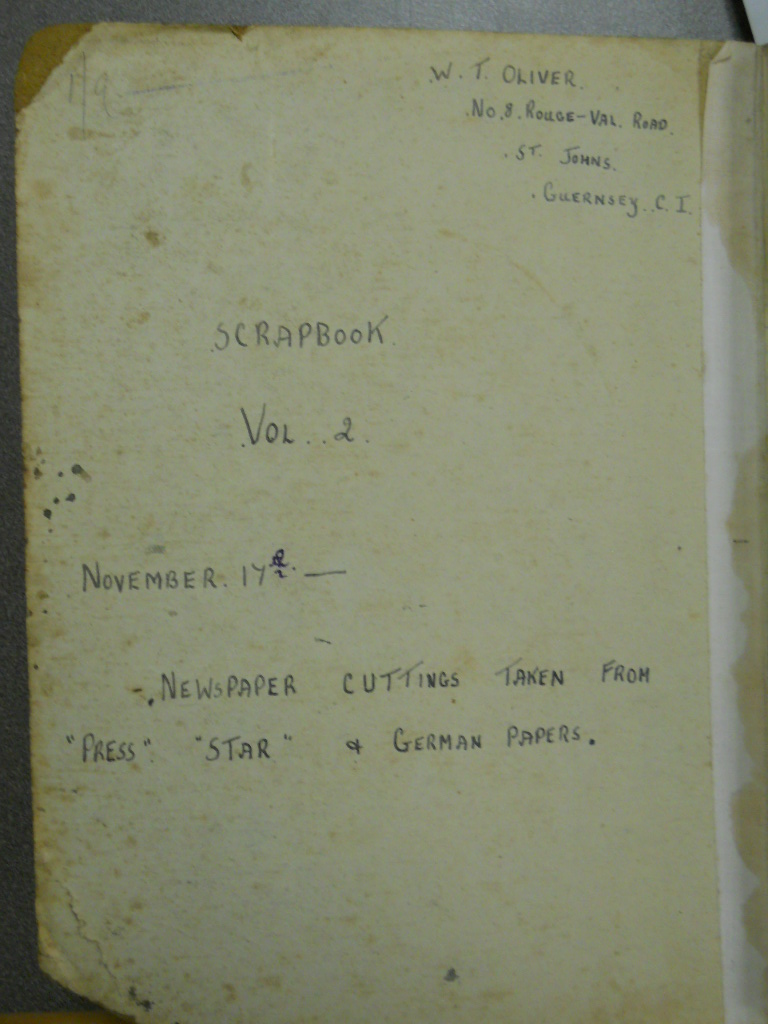

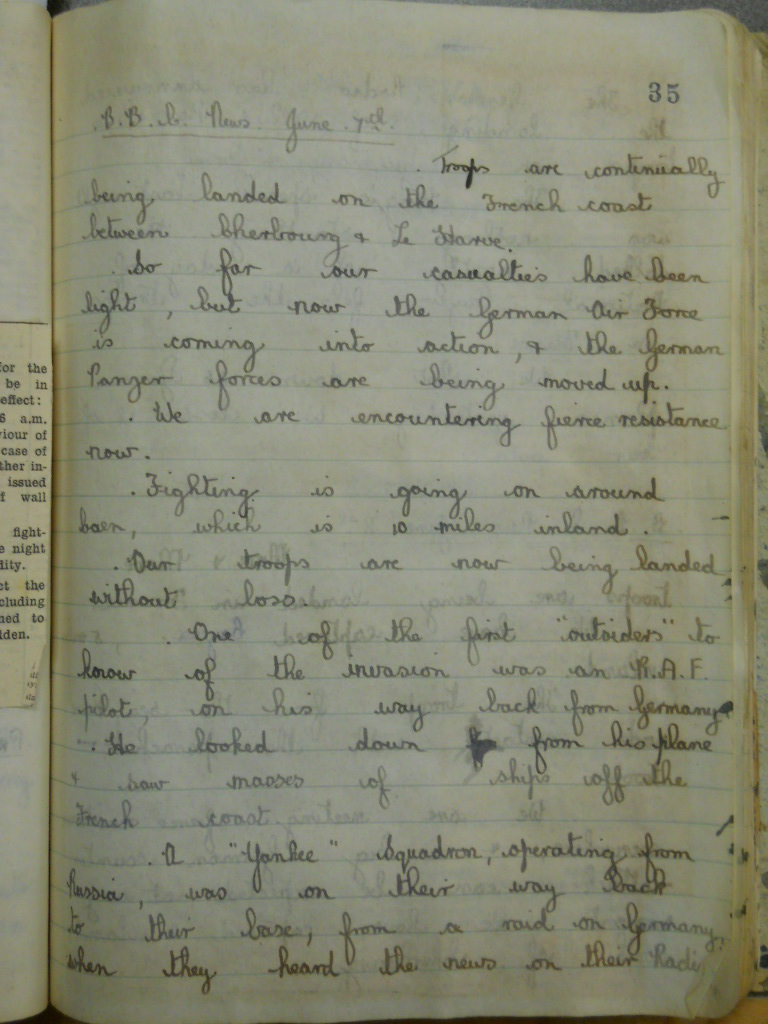

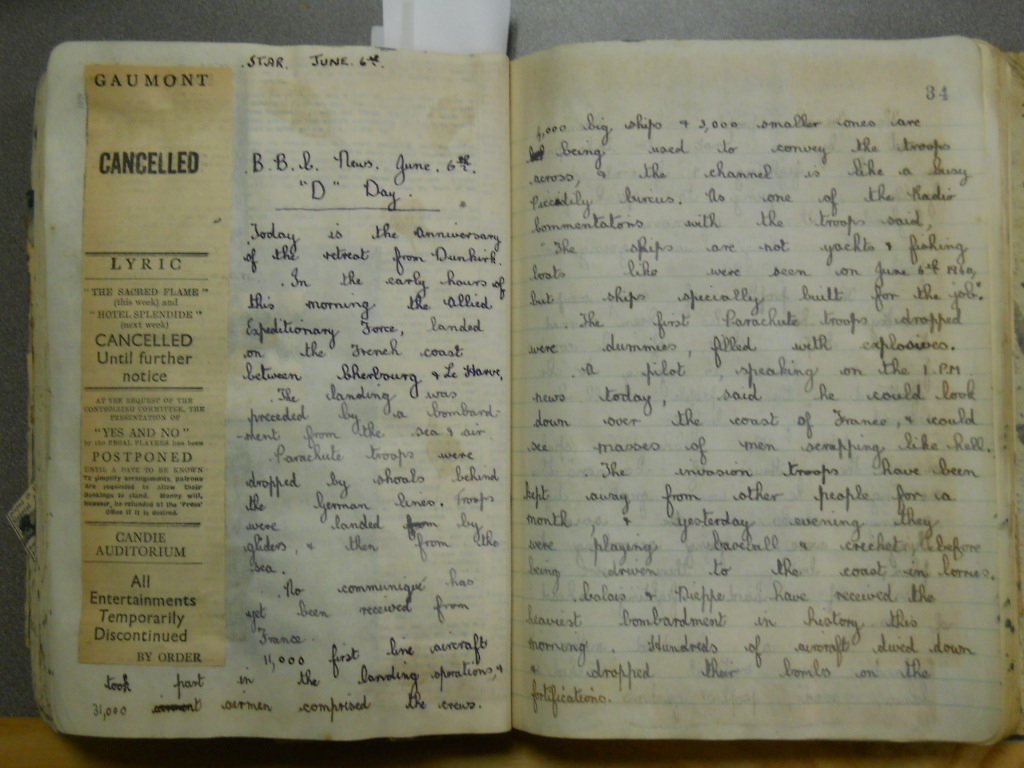

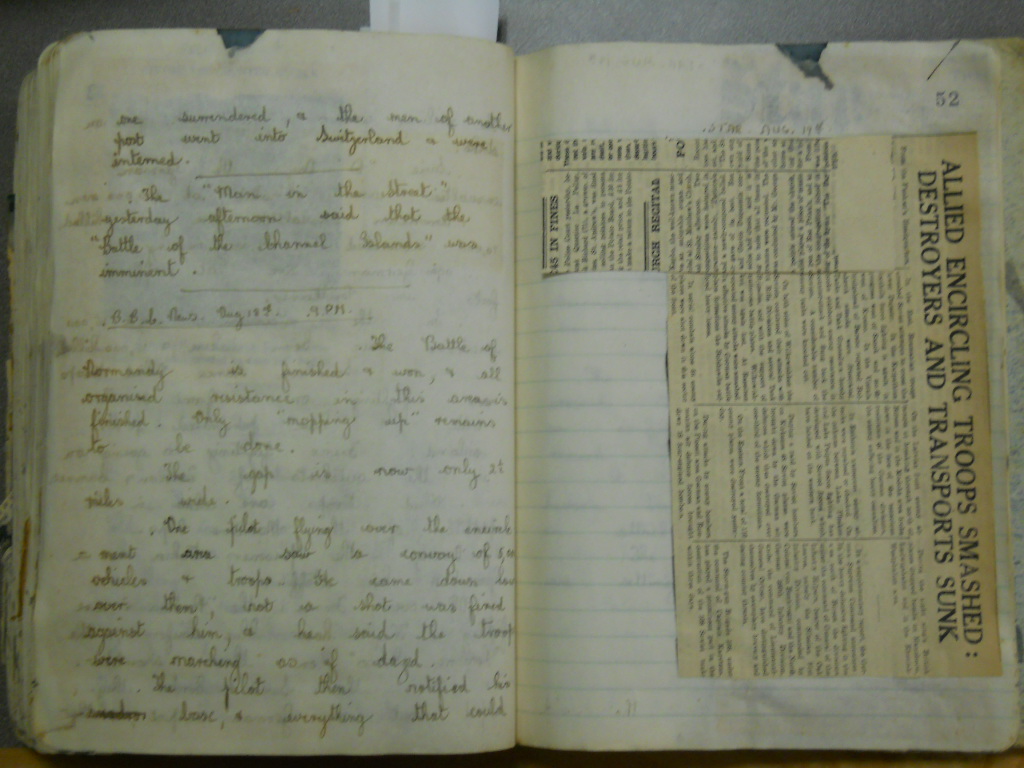

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department holds an unusual scrapbook created in the Channel Islands during World War II. The scrapbook, made by “W.T. Oliver, 8 Rouge-Val Road, St Johns, Guernsey,” ranges in date from November 16, 1943, to August 21, 1944, and also contains a letter from August 25, 1945. Entitled “Volume 2” (the location of Volume 1 is unknown), the book includes handwritten records of BBC war broadcasts—illegal at the time—juxtaposed with newspaper clippings of German wartime reports from local commandeered newspapers on the island of Guernsey.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department holds an unusual scrapbook created in the Channel Islands during World War II. The scrapbook, made by “W.T. Oliver, 8 Rouge-Val Road, St Johns, Guernsey,” ranges in date from November 16, 1943, to August 21, 1944, and also contains a letter from August 25, 1945. Entitled “Volume 2” (the location of Volume 1 is unknown), the book includes handwritten records of BBC war broadcasts—illegal at the time—juxtaposed with newspaper clippings of German wartime reports from local commandeered newspapers on the island of Guernsey.

To understand the import of this Guernsey scrapbook, one must first understand Guernsey’s status and role during World War II. Guernsey is one of two autonomous island groupings (the other is Jersey) that make up the Channel Islands, located in the English Channel northwest of the French coast.  The Channel Islands are British Crown dependencies, though they are not part of the United Kingdom. The islands have both the honor of being the oldest possessions of the British Crown and the more dubious distinction of being the only British soil occupied by Germany during World War II. Realizing that they could not properly defend the Channel Islands at the start of the war, and seeing only minimal strategic importance in the islands, the British demilitarized the region in 1940 to try to prevent military targeting and bloodshed within the archipelago. The British also offered to pay for the evacuation of all Channel Island residents to England. However, only half of the islands’ residents had evacuated (primarily draft-age men, children and some women) when Germany—which had not learned of the British demilitarization—bombed Guernsey’s main harbor on June 28, 1940, killing or critically injuring over sixty residents. Two days later, the Germans quickly and quietly occupied the entirety of the Channel Islands, announcing the regime change to residents via requisitioned local papers on July 1.

The Channel Islands are British Crown dependencies, though they are not part of the United Kingdom. The islands have both the honor of being the oldest possessions of the British Crown and the more dubious distinction of being the only British soil occupied by Germany during World War II. Realizing that they could not properly defend the Channel Islands at the start of the war, and seeing only minimal strategic importance in the islands, the British demilitarized the region in 1940 to try to prevent military targeting and bloodshed within the archipelago. The British also offered to pay for the evacuation of all Channel Island residents to England. However, only half of the islands’ residents had evacuated (primarily draft-age men, children and some women) when Germany—which had not learned of the British demilitarization—bombed Guernsey’s main harbor on June 28, 1940, killing or critically injuring over sixty residents. Two days later, the Germans quickly and quietly occupied the entirety of the Channel Islands, announcing the regime change to residents via requisitioned local papers on July 1.

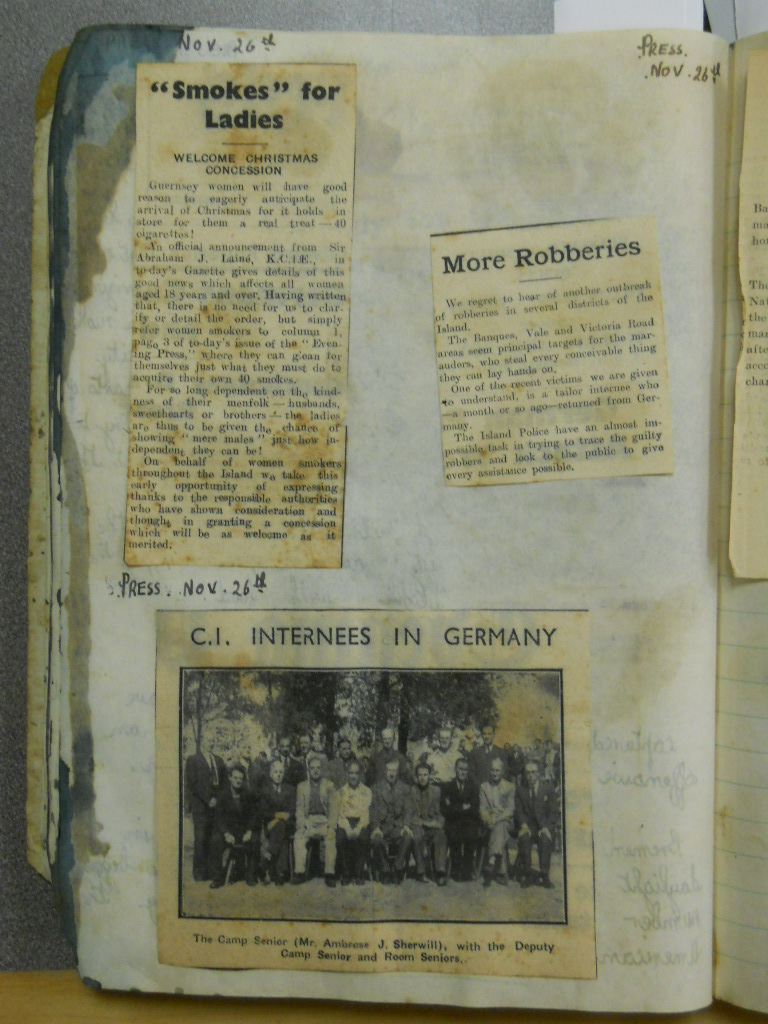

Until the Channel Islands’ liberation by the Allies on May 9, 1945, the residents lived uneasily under German occupying forces. On Guernsey, the two local newspapers—the Star and the Evening Press—continued publication throughout the German occupation, but remained heavily censored and full of propaganda, issued by the “Commandant” upon orders of the “German Supreme Command” from the “Fuhrer’s Headquarters.” Resident Ralph Durand would later explain that the occupation, at first, seemed to be a “benevolent despotism,” as “there seemed nothing particularly tyrannous about the German Commandant’s orders.” The German forces instated curfews, though they were not always enforced, and appropriated some buildings and transport for military use. A few citizens immediately collaborated with (and/or dated) the Germans, but the majority neither abetted nor obviously resisted the invading army. For most, the greatest hardship was the strict rationing of food and fuel—rationing that would lead to near-starvation and freezing at points during the winters of 1944 and 1945—but that was true throughout much of Europe during the war. A member of Guernsey’s royal court, Rev. John Leale, argued that “we shall associate the occupation with hunger and cold and homelessness rather than with dramatic arrests and sensational sentences.”[1]

Until the Channel Islands’ liberation by the Allies on May 9, 1945, the residents lived uneasily under German occupying forces. On Guernsey, the two local newspapers—the Star and the Evening Press—continued publication throughout the German occupation, but remained heavily censored and full of propaganda, issued by the “Commandant” upon orders of the “German Supreme Command” from the “Fuhrer’s Headquarters.” Resident Ralph Durand would later explain that the occupation, at first, seemed to be a “benevolent despotism,” as “there seemed nothing particularly tyrannous about the German Commandant’s orders.” The German forces instated curfews, though they were not always enforced, and appropriated some buildings and transport for military use. A few citizens immediately collaborated with (and/or dated) the Germans, but the majority neither abetted nor obviously resisted the invading army. For most, the greatest hardship was the strict rationing of food and fuel—rationing that would lead to near-starvation and freezing at points during the winters of 1944 and 1945—but that was true throughout much of Europe during the war. A member of Guernsey’s royal court, Rev. John Leale, argued that “we shall associate the occupation with hunger and cold and homelessness rather than with dramatic arrests and sensational sentences.”[1]

Despite Durand’s and Leale’s assertions, life on the Channel Islands under German rule was not entirely “benevolent,” nor was it absent of resistance and, by consequence, detention and punishment. Outnumbered by a large and well-armed German military force, and in light of their own low chance of escape due to island geography, island residents knew that large-scale resistance would lead to equivalent and likely bloody retaliation. Even so, residents regularly committed small acts of sabotage, cutting cable lines and defusing mines. When the German regime imported Jews and other political prisoners from across Europe to slave labor camps on the islands (the only instance of Nazi concentration camps on British soil), some local residents publicly objected to the prisoners’ harsh treatment and offered the prisoners food, shelter, and hiding places, in cases of escape. Similarly, when in late 1942 the occupying regime announced that all Jewish residents and non-Channel-Islands citizens (British and otherwise) would be sent to camps in Germany, local Guernsey residents protested the deportations by assembling en masse on the public docks at the deportees’ time of departure.

Despite Durand’s and Leale’s assertions, life on the Channel Islands under German rule was not entirely “benevolent,” nor was it absent of resistance and, by consequence, detention and punishment. Outnumbered by a large and well-armed German military force, and in light of their own low chance of escape due to island geography, island residents knew that large-scale resistance would lead to equivalent and likely bloody retaliation. Even so, residents regularly committed small acts of sabotage, cutting cable lines and defusing mines. When the German regime imported Jews and other political prisoners from across Europe to slave labor camps on the islands (the only instance of Nazi concentration camps on British soil), some local residents publicly objected to the prisoners’ harsh treatment and offered the prisoners food, shelter, and hiding places, in cases of escape. Similarly, when in late 1942 the occupying regime announced that all Jewish residents and non-Channel-Islands citizens (British and otherwise) would be sent to camps in Germany, local Guernsey residents protested the deportations by assembling en masse on the public docks at the deportees’ time of departure.

By far the most common small act of resistance, however, involved owning and listening to the radio. Following a few short-term bans on radio ownership early in the war, the German occupiers banned resident radio ownership entirely in June 1942 for security reasons. If found in possession of a radio, Channel Islands residents could be punished with exorbitant fines, imprisonment, hard labor, or even death.

By far the most common small act of resistance, however, involved owning and listening to the radio. Following a few short-term bans on radio ownership early in the war, the German occupiers banned resident radio ownership entirely in June 1942 for security reasons. If found in possession of a radio, Channel Islands residents could be punished with exorbitant fines, imprisonment, hard labor, or even death.

In response, some residents turned in their radios, then built their own crystal radio receivers according to specifications noted on the BBC; others hid their radios in “prams, manure heaps, beds, even… a washtub full of soapsuds.”[2] Still others organized news services, like the Guernsey Underground News Service (GUNS), whose members secretly recorded BBC reports in shorthand and then distributed the information via word of mouth or printed news briefs to hundreds of their fellow islanders. These secret news services were so successful that even when the punishment for radio ownership was most dire, the Allies’ major wartime successes were known across the islands within two hours of key BBC broadcasts. This ability to circumvent German information censors greatly boosted morale among islanders, and also greatly diminished the morale of German soldiers, leaving them jittery and on edge throughout their island occupation.

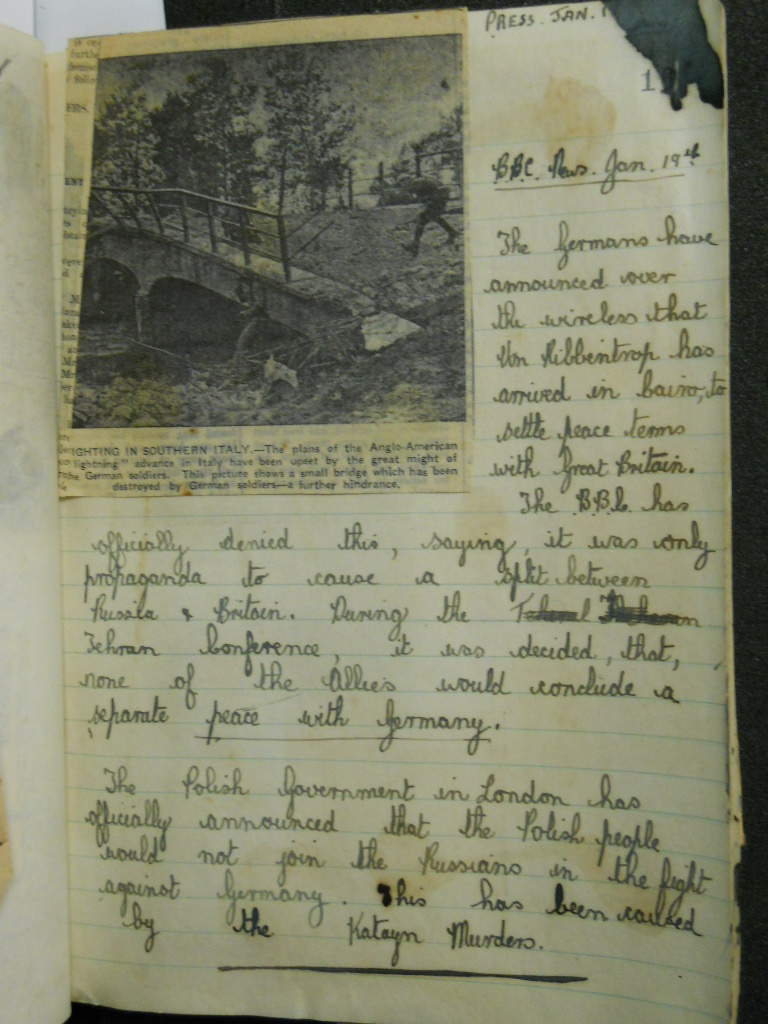

The Guernsey scrapbook held by Brandeis’ Special Collections is one such illegal record of a Guernsey resident who documented BBC broadcasts. The scrapbook details BBC reports of the Allies’ battle successes and bombing raids—news that likely offered much-needed hope to war-weary Guernsey residents. Technology is a theme throughout the text, with comprehensive notes on BBC reports of Flying Fortresses and other aeronautical inventions of the Allies combining with German photos from local Guernsey newspapers of Messerschmitt jet fighters and Panther tanks.

The Guernsey scrapbook held by Brandeis’ Special Collections is one such illegal record of a Guernsey resident who documented BBC broadcasts. The scrapbook details BBC reports of the Allies’ battle successes and bombing raids—news that likely offered much-needed hope to war-weary Guernsey residents. Technology is a theme throughout the text, with comprehensive notes on BBC reports of Flying Fortresses and other aeronautical inventions of the Allies combining with German photos from local Guernsey newspapers of Messerschmitt jet fighters and Panther tanks.

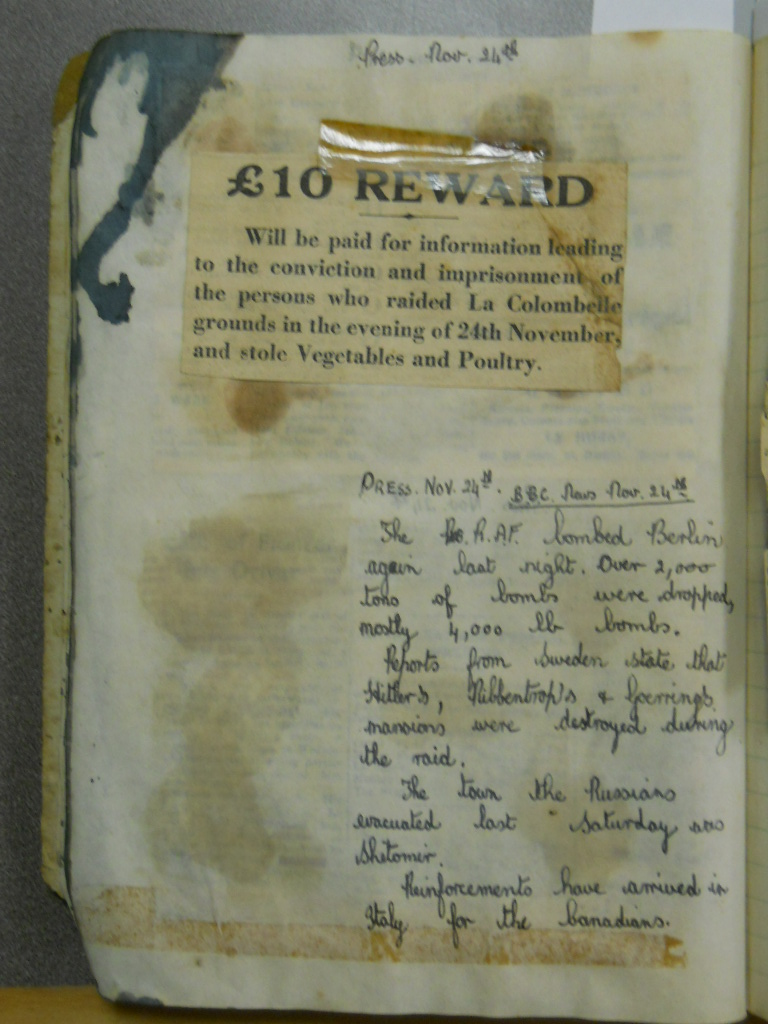

In addition to military technology and bombing raids, the scrapbook also gives insight into the day-to-day wartime experiences of Guernsey residents. Alongside the BBC broadcasts, newsclippings from Guernsey’s local papers, the Star and the Evening Press, reveal the practical realities of life on the occupied island. Numerous clippings record the changing ration rules for food, fuel and “luxuries” (for example, women were given extra cigarette rations at Christmas in 1943). Other clippings reflect the increasing restrictions experienced by islanders under German occupation, including announcements (in English and German) of extended curfews, limited coastal access, prohibitions on certain items (like radios) and penalties for ignoring regulations. The scrapbook also contains articles that follow the prosecution and punishment of local residents for sabotage and theft, both common occurrences as war tensions increased and rations became scarce.

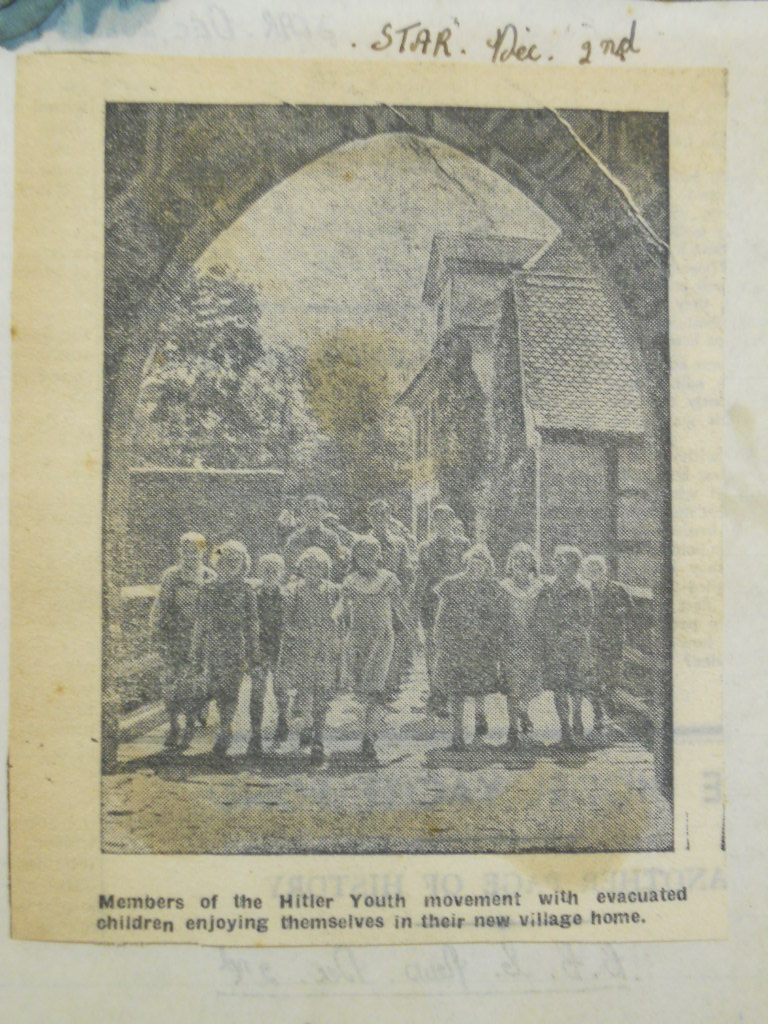

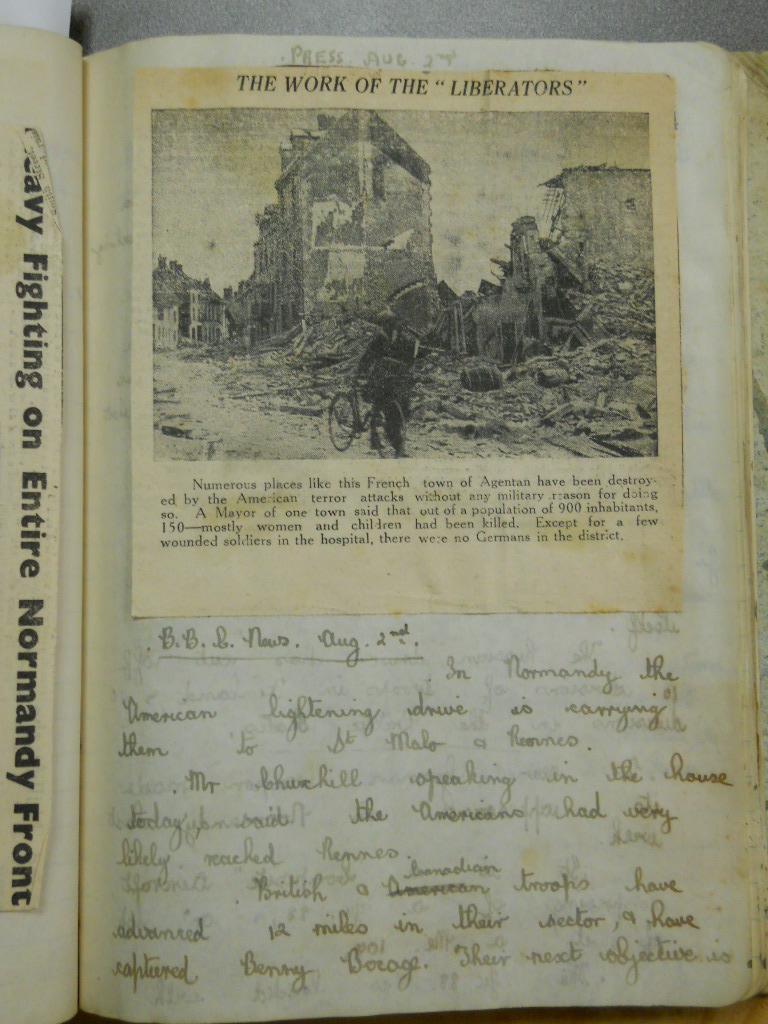

The scrapbook is perhaps most valuable for its fascinating record of comparative wartime propaganda. While certain of the BBC reports describe Allied bombing raids in terms of factories or military camps destroyed, Nazi-influenced Star and Evening Press newsclippings of the same events detail the “terror attacks” of the “British air gangsters” and the “yankee monster,” who are “causing terror and devastation in the quiet suburbs” through the use of “phosphorous bombs against women and children” and the destruction of famous cultural and religious institutions. One clipping focuses on a shot-down Allied airman whose squadron was named “Murder, Inc.,” implying that murder is the only goal of these “enemy terror airmen.” Likewise, the BBC broadcasts present bombing raids of London or other English cities in human terms, while newsclippings of German reports focus on the military targets demolished. Other propagandistic scrapbook entries similarly work in parallel. Summaries of BBC broadcasts depict the Allies’ care for civilians in bombed German cities, while Nazi-influenced newsclippings depict Hitler Youth walking with young Guernsey “evacuees” in German camps and praise the treatment of such prisoners, who “are in need of nothing—more than our prayers for continued health and prosperity.”

The scrapbook is perhaps most valuable for its fascinating record of comparative wartime propaganda. While certain of the BBC reports describe Allied bombing raids in terms of factories or military camps destroyed, Nazi-influenced Star and Evening Press newsclippings of the same events detail the “terror attacks” of the “British air gangsters” and the “yankee monster,” who are “causing terror and devastation in the quiet suburbs” through the use of “phosphorous bombs against women and children” and the destruction of famous cultural and religious institutions. One clipping focuses on a shot-down Allied airman whose squadron was named “Murder, Inc.,” implying that murder is the only goal of these “enemy terror airmen.” Likewise, the BBC broadcasts present bombing raids of London or other English cities in human terms, while newsclippings of German reports focus on the military targets demolished. Other propagandistic scrapbook entries similarly work in parallel. Summaries of BBC broadcasts depict the Allies’ care for civilians in bombed German cities, while Nazi-influenced newsclippings depict Hitler Youth walking with young Guernsey “evacuees” in German camps and praise the treatment of such prisoners, who “are in need of nothing—more than our prayers for continued health and prosperity.”

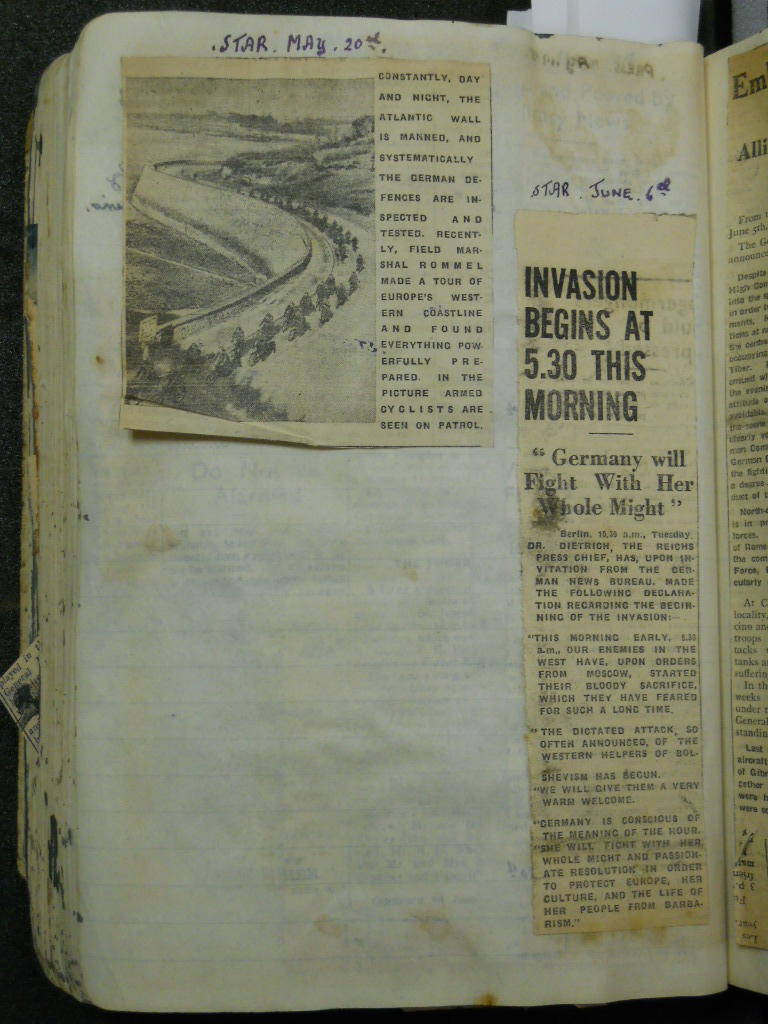

The scrapbook’s combination of BBC broadcasts and Nazi war reports creates a particularly chilling reflection of the war in the days surrounding June 6, 1944, later known as D-Day, the day of the Allied invasion of Normandy. While scrapbook entries suggest that BBC broadcasts were silent on the topic prior to June 6, rumors of the invasion were evident in Nazi-controlled Guernsey papers in late May. On June 6, the Star published an ominous report from the German Supreme Command:

The scrapbook’s combination of BBC broadcasts and Nazi war reports creates a particularly chilling reflection of the war in the days surrounding June 6, 1944, later known as D-Day, the day of the Allied invasion of Normandy. While scrapbook entries suggest that BBC broadcasts were silent on the topic prior to June 6, rumors of the invasion were evident in Nazi-controlled Guernsey papers in late May. On June 6, the Star published an ominous report from the German Supreme Command:

This morning early, 5:30 a.m., our enemies in the west have, upon orders from Moscow, started their bloody sacrifice, which they have feared for such a long time. The dictated attack, so often announced, of the western helpers of bolshevism has begun. We will give them a very warm welcome. Germany is conscious of the meaning of the hour. She will fight with her whole might and passionate resolution in order to protect Europe, her culture and the life of her people from barbarism.”

The sarcasm and threat implied in this statement, published in a German-commandeered but English newspaper, reflect the underlying tension and menace that was the norm in wartime occupied Guernsey. In turn, the fact that this scrapbook newsclipping is followed by extensive BBC broadcast notes on the Allies’ D-Day successes demonstrates how BBC radio access helped maintain islanders’ morale.

Sadly, items similar to this Guernsey scrapbook, proving illegal wartime radio use, caused numerous Guernsey residents to be imprisoned over the course of World War II. In a number of cases, these individuals were sent to their deaths in Nazi camps across Europe. For example, the five leaders of GUNS, Guernsey’s secret BBC news service, were betrayed by informers in 1944; at least one died due to his resulting incarceration in Nazi camps. In all, over 2000 Channel Islanders were deported to prison camps, including both men and women, elderly individuals and children, for “crimes” ranging from radio listening, minor sabotage and prisoner aid to the simple fact of identification as a non-Channel Islands citizen or as a Jew.

Sadly, items similar to this Guernsey scrapbook, proving illegal wartime radio use, caused numerous Guernsey residents to be imprisoned over the course of World War II. In a number of cases, these individuals were sent to their deaths in Nazi camps across Europe. For example, the five leaders of GUNS, Guernsey’s secret BBC news service, were betrayed by informers in 1944; at least one died due to his resulting incarceration in Nazi camps. In all, over 2000 Channel Islanders were deported to prison camps, including both men and women, elderly individuals and children, for “crimes” ranging from radio listening, minor sabotage and prisoner aid to the simple fact of identification as a non-Channel Islands citizen or as a Jew.

Due to the risks involved in its creation, the Guernsey scrapbook housed in Brandeis’ Special Collections is a testament to the determination of Guernsey residents to maintain their hope in and patriotic connection with England in the face of years of German occupation. As important, the text offers an uncommon combination of material, documenting the wartime views and propaganda of opposing sides in the World War II conflict.

Due to the risks involved in its creation, the Guernsey scrapbook housed in Brandeis’ Special Collections is a testament to the determination of Guernsey residents to maintain their hope in and patriotic connection with England in the face of years of German occupation. As important, the text offers an uncommon combination of material, documenting the wartime views and propaganda of opposing sides in the World War II conflict.

Notes

- Ralph Durand, Guernsey Under German Rule (London: The Guernsey Society, 1946), 29.

- Madeleine Bunting, The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940-1945 (London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 1995), 209.

Sources

Bunting, Madeleine. The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940-1945. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1995.

Bunting, Madeleine. The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940-1945. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1995.

Cohen, Frederick. The Jews in the Channel Islands during the German Occupation, 1940-1945. St Helier, Jersey: Jersey Heritage Trust, 2000.

Cruikshank, Charles. The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Durand, Ralph. Guernsey Under German Rule. The Guernsey Society. London, 1946.