1950-1951

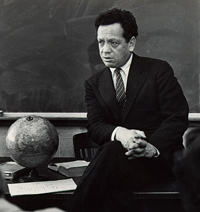

In order to counter a scheduled appearance at their campus by the Communist-baiting Wisconsin Senator Joe McCarthy, students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison invited Brandeis Professor Max Lerner to speak on the same day. When the chairman of the medical school there accused Lerner of having joined the Communist party in 1938, the University of Wisconsin administration refused Lerner the right to speak. In a statement to The Daily Cardinal, the student newspaper, Lerner denied the charge that he was a Communist: "I never was and never could be."

Faculty and students at Madison overturned the administration's decision, and Lerner spoke there before a large and enthusiastic audience. By contrast, McCarthy's appearance hours earlier, sponsored by the local chapter of the Young Republicans, had been weakly attended and heckled by the few non-believers who did come. The interstate event was a minor skirmish, but it proved an early indication of the friction liberal Brandeis would periodically experience during the increasingly paranoid "Red Scare" era.

— Staff

As American military involvement in Korea escalated and President Truman reinstated the draft, concern about the impact these events could have on Brandeis took center stage near the end of the fall semester. The loss of students to military service during World War II had been the final blow to Middlesex University, Brandeis' predecessor. In only its third year with a student population of less than 500, Brandeis seemed vulnerable to a similar fate.

President Sachar refused to give into pessimism. If called upon as an institution, he said, Brandeis would make every effort to be of use to the war effort, but draft or no draft, plans for the University’s continued development would be neither stopped nor slowed. In April, Truman issued an executive order granting deferments to most of the country's college students, alleviating any immediate threat to the university's well-being.

— Staff

Despite the eternally visible (and audible) presence of construction crews on campus, the pace of physical improvements occasionally seemed unbearably slow by the third year of the Brandeis experiment, testing the temperaments of the students who had willingly dedicated themselves to the cause. Even the new facilities sometimes worked to challenge their resolve. In the new Ridgewood Quad broken pipes led to extended periods without heat, compounded by the swamp of ankle-deep mud between the dorms and the center of campus, dubbed by residents the "Ridgewood Quagmire." Damp and frustrated students voiced their discontent in The Justice, but they understood as well as the administration that conditions would only improve with time.

— Staff