Background

After the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and in anticipation of the passing of the Voter Rights Act in 1965, the focus of the Civil Rights movement started to shift from resisting the segregation laws in the South to establishing a more fundamental equality by focusing on voter registration and politics. The SCOPE Project was created with the goal of increasing voter registration, educating citizens on the voter registration process, and, if needed, participating in protests or demonstrations in response to efforts to deny African Americans the right to vote. During this period, many local and state governments in the South still enforced literacy tests designed to prevent African Americans from registering to vote. Harassment and intimidation by police and white citizens further impeded voter registration.

After the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and in anticipation of the passing of the Voter Rights Act in 1965, the focus of the Civil Rights movement started to shift from resisting the segregation laws in the South to establishing a more fundamental equality by focusing on voter registration and politics. The SCOPE Project was created with the goal of increasing voter registration, educating citizens on the voter registration process, and, if needed, participating in protests or demonstrations in response to efforts to deny African Americans the right to vote. During this period, many local and state governments in the South still enforced literacy tests designed to prevent African Americans from registering to vote. Harassment and intimidation by police and white citizens further impeded voter registration.

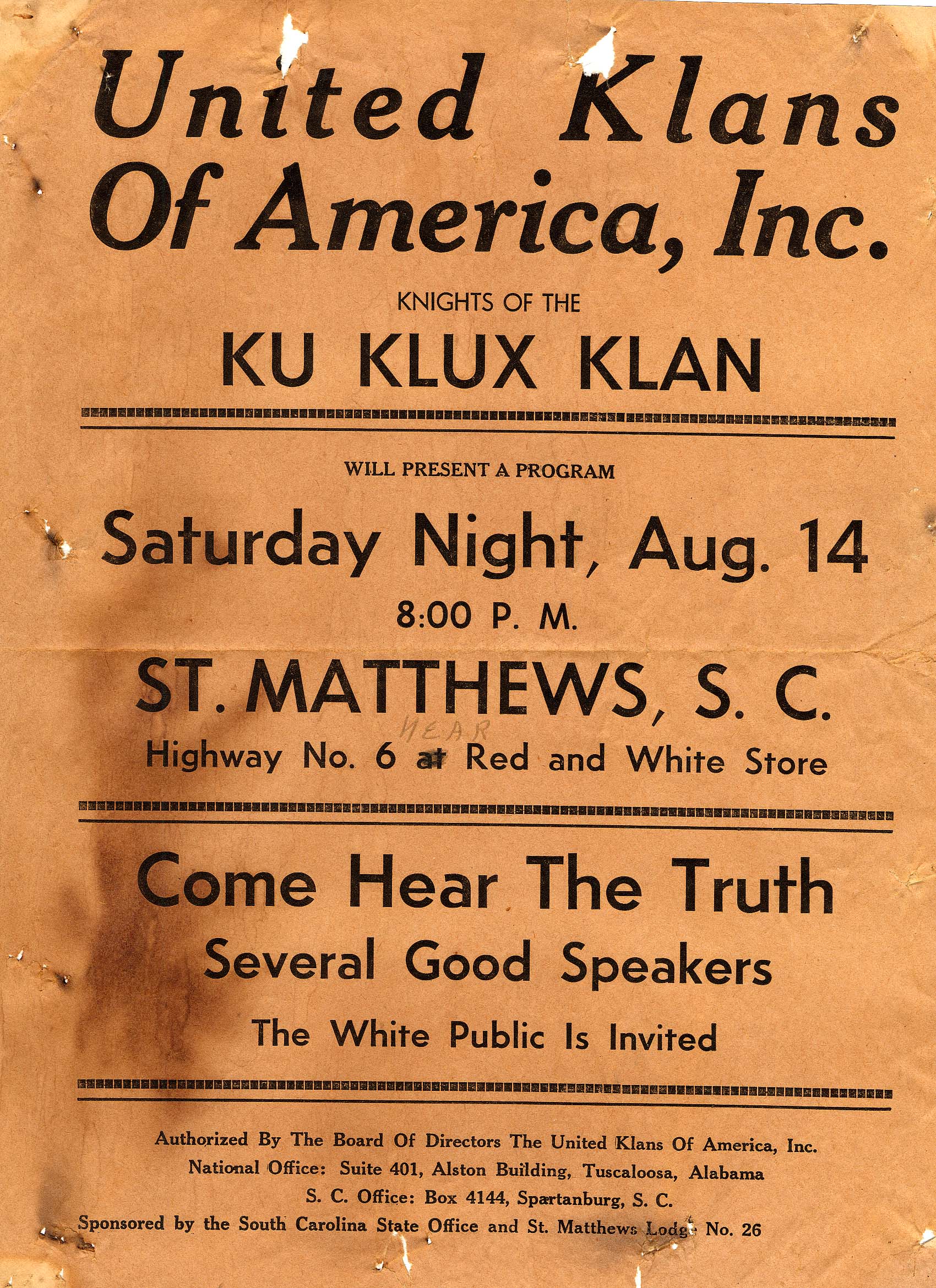

Ku Klux Klan pamphlet, Calhoun County, SC 1965

Ku Klux Klan pamphlet, Calhoun County, SC 1965

There was an atmosphere of real danger and fear for civil rights workers in the South. Freedom Riders attempting to integrate the interstate bus system had been severely beaten, and one of the buses was burned. Three civil rights workers had been killed in Mississippi during 1964’s Freedom Summer. Many other civil rights workers had been beaten or killed. The police routinely stood aside (or even participated) and let these violent acts occur, and all-white juries routinely acquitted the perpetrators. The SCLC hoped that the presence of large numbers of white college students involved in the SCOPE Project would attract the attention of the media and the nation, making the segregationist power structure more reluctant to resort to brutal tactics in trying to prevent African Americans from exercising their civil rights. This attention would, it was hoped, put pressure on the federal government to take steps to protect Civil Rights workers and citizens in the South.

Bayard Rustin, SCOPE training, Atlanta, GA, 1965

Bayard Rustin, SCOPE training, Atlanta, GA, 1965

Lynn Goldsmith joined the SCOPE Project through Brandeis University and was one of approximately twenty-five students from Brandeis who participated in the project. The Brandeis group traveled to Atlanta, Georgia, where all SCOPE Project volunteers received training from veteran leaders in the Civil Rights movement such as Bayard Rustin, Hosea Williams, and James Bevel. The Brandeis group then traveled to Charleston, South Carolina, and began canvassing voters for registration. However, after a few weeks it became apparent that the group was too large and unwieldy. The Brandeis group agreed that smaller groups should go live in rural communities where there was a more urgent need for voter registration and education. Lynn was in a small group that went to the rural South Carolina town of St. Matthews, in Calhoun County.

Voter education, Calhoun County, SC, 1965

Voter education, Calhoun County, SC, 1965

In Calhoun County the group worked with local Civil Rights activists, ministers, and high school and college students to canvas the area, work on voter registration, and inrease voter education.

Lynn’s diary describes her experiences in South Carolina. She recorded a diary entry for each day, and the entries capture all the different experiences, thoughts, and feelings of a young civil rights worker in the South. The diary details the welcoming reception the SCOPE workers received from the local African American community (once they had earned their trust); the friendships and connections Lynn made; the harassment from the white power structure and white citizens; the journey to the SCLC conference in Birmingham, Alabama; Lynn’s attendance at a speech by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; her arrest at a demonstration during a voter registration day; and the other obstacles and challenges these young civil rights workers faced while trying to canvas and register voters.

Lynn Goldsmith’s parents strongly supported her and were an inspiration for her to participate in the Civil Rights movement. Her father was also very involved in the Civil Rights movement and other social justice movements. During her time in South Carolina, Lynn mailed her diary entries to her father every day. Her father would then mail them to a group of friends and family to give them updates. Lynn’s parents also sent packages of books and materials for the citizen education programs and visited her in South Carolina.