The First Bookplate

Description by Adam Rutledge, Senior University Archives and Special Collections Assistant and PhD candidate in English and American literature

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections at Brandeis has the distinction of holding an example of the earliest known bookplate, which comes from the collection of Brother Hildebrand (Hilpbrand) Brandenburg of Biberach. Scholars date the bookplate to the 1470s, and it must have been completed by 1480, at which time Hildebrand, a Carthusian monk, donated his collection, accompanied by these bookplates, to his monastery in Buxheim.

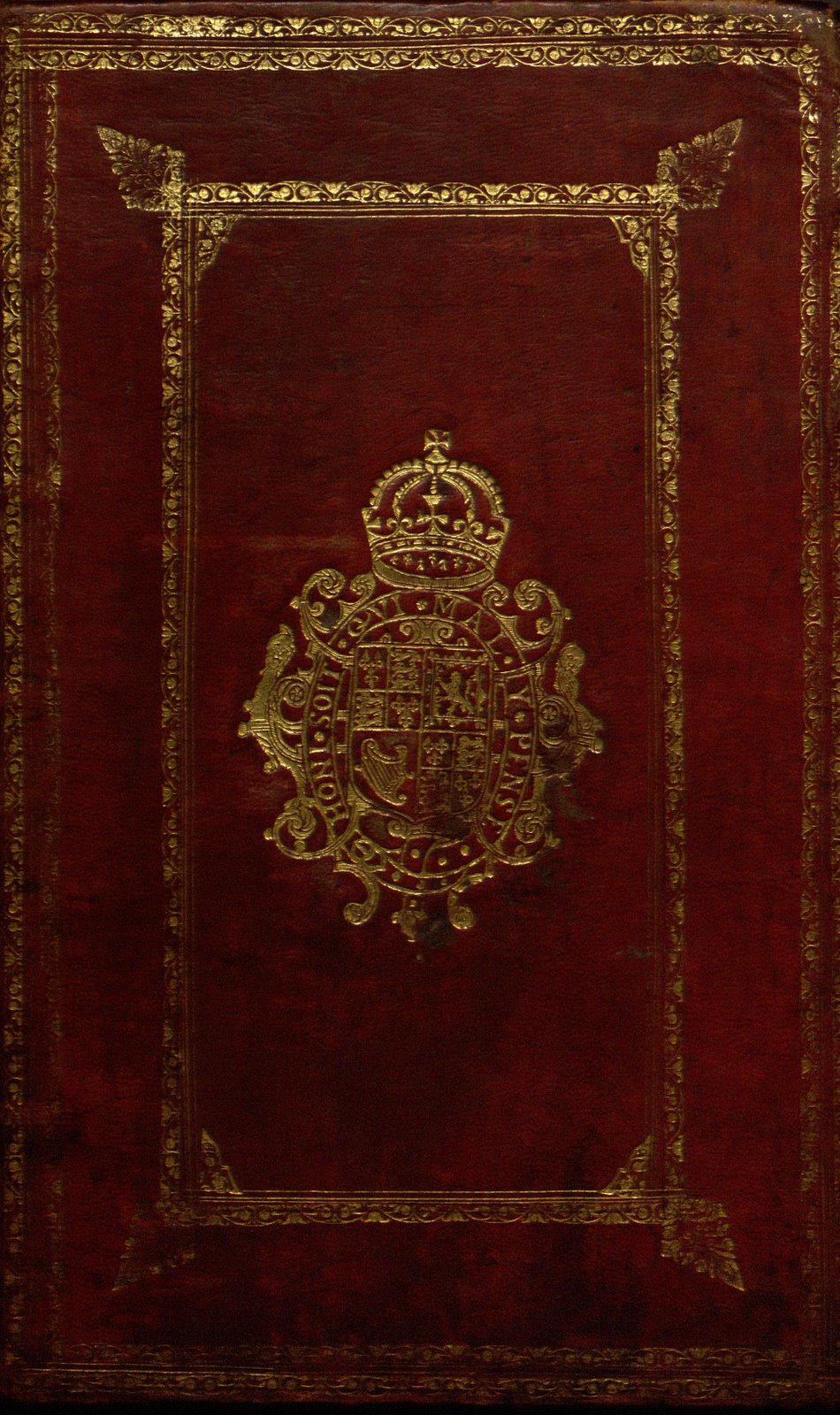

The convention of pasting a bookplate,  also known as an ex libris (“from the library of…”), into the volumes in one’s personal library began in Germany in the late 15th century and only gradually spread to France, Italy, England and the rest of Europe. Even after the advent of printing and the beginning of mass production of books in the latter part of the 15th century, the possession of large libraries long remained the privilege of the elite. Thus bookplates, which signified the ownership of volumes or functioned as gift plates to record the giver of a large donation, tended to be heavily armorial in nature, constructed around the family crests of their noble owners. This phenomenon is akin to the production of armorial bindings, in which the books owned by a particular noble family would all be bound in identical leather, with the arms of the owner elaborately blazoned on the cover of each volume. One striking example of this style of binding may be seen in Brandeis’ copy of Brief animadversions on amendments of…the institvtes of the lawes of England, which was once part of the royal library of King Charles II and is beautifully bound in red morocco gilt, with the king’s arms gilt-stamped upon both the front and rear covers.

also known as an ex libris (“from the library of…”), into the volumes in one’s personal library began in Germany in the late 15th century and only gradually spread to France, Italy, England and the rest of Europe. Even after the advent of printing and the beginning of mass production of books in the latter part of the 15th century, the possession of large libraries long remained the privilege of the elite. Thus bookplates, which signified the ownership of volumes or functioned as gift plates to record the giver of a large donation, tended to be heavily armorial in nature, constructed around the family crests of their noble owners. This phenomenon is akin to the production of armorial bindings, in which the books owned by a particular noble family would all be bound in identical leather, with the arms of the owner elaborately blazoned on the cover of each volume. One striking example of this style of binding may be seen in Brandeis’ copy of Brief animadversions on amendments of…the institvtes of the lawes of England, which was once part of the royal library of King Charles II and is beautifully bound in red morocco gilt, with the king’s arms gilt-stamped upon both the front and rear covers.

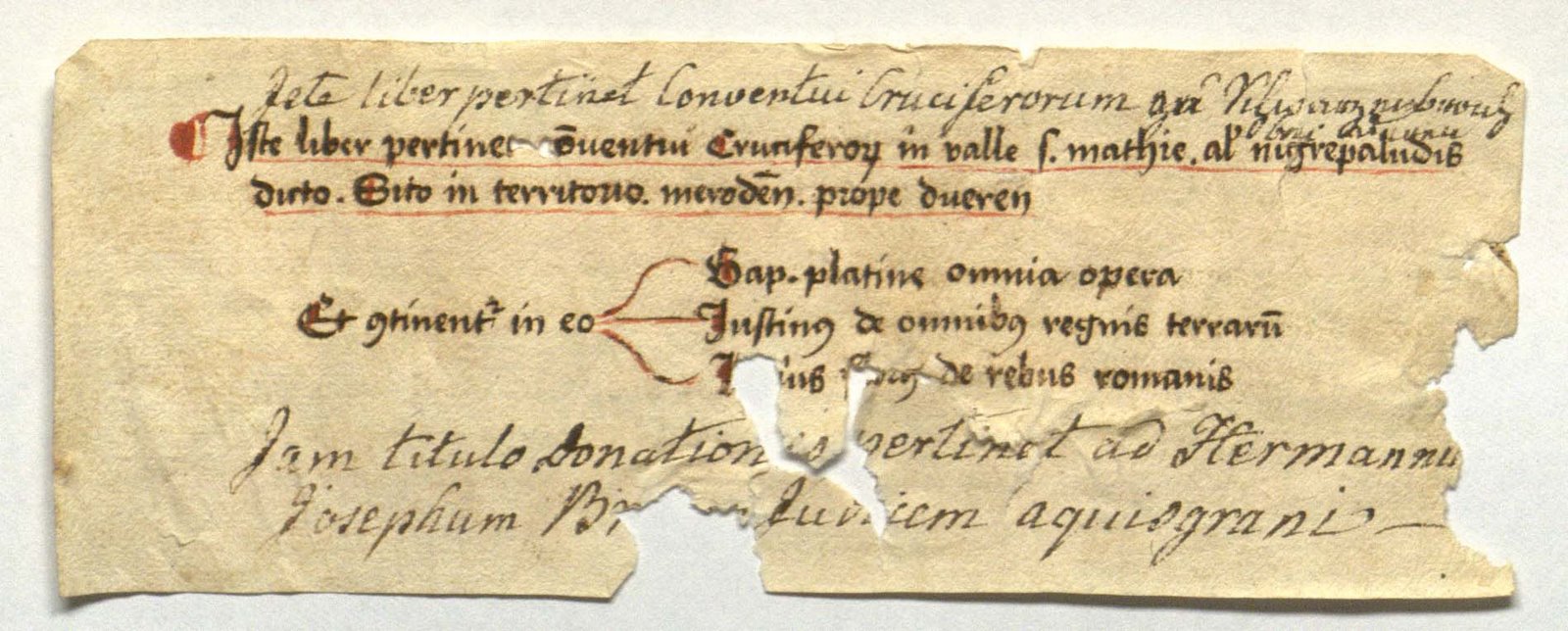

These elaborate displays of ownership, whether appearing on the book’s cover or inside in the form of a bookplate, gradually replaced the earlier custom of ownership inscriptions found, particularly in manuscripts, either inside the front cover or at the close, following the colophon. These often begin Iste liber pertinet… (“This book belongs to…”), as seen in this fine example, originally pasted into Bartolomeo de Sacchi di Piadena’s Bap. Platinae cremonensis, de vitis ac gestis summorum (Coloniae, 1540). [The fragment containing the inscription is now catalogued independently as Manus 33.]

These elaborate displays of ownership, whether appearing on the book’s cover or inside in the form of a bookplate, gradually replaced the earlier custom of ownership inscriptions found, particularly in manuscripts, either inside the front cover or at the close, following the colophon. These often begin Iste liber pertinet… (“This book belongs to…”), as seen in this fine example, originally pasted into Bartolomeo de Sacchi di Piadena’s Bap. Platinae cremonensis, de vitis ac gestis summorum (Coloniae, 1540). [The fragment containing the inscription is now catalogued independently as Manus 33.]

Bookplates provide a unique resource for scholars, as they enable them to trace the history of particular volumes as well as map the transmission of texts in the early days of printing. The history of the ownership of a book, known as its provenance, often provides information as to who may have been reading what books, and has even enabled the intellectual reconstruction of famous libraries, both of individuals and institutions. It can be invaluable for a scholar to piece together the resources a particular author, scientist or historian had at his or her disposal when composing his or her own work, and a bookplate can be an important tool in this process. In the rare book market, particularly important bookplates can dramatically raise the value of volumes, and books that have always remained in private hands rather than in institutions and are accompanied by a well-documented provenance, which may include evidence drawn from bookplates, are particularly desirable for collectors.

Bookplates provide a unique resource for scholars, as they enable them to trace the history of particular volumes as well as map the transmission of texts in the early days of printing. The history of the ownership of a book, known as its provenance, often provides information as to who may have been reading what books, and has even enabled the intellectual reconstruction of famous libraries, both of individuals and institutions. It can be invaluable for a scholar to piece together the resources a particular author, scientist or historian had at his or her disposal when composing his or her own work, and a bookplate can be an important tool in this process. In the rare book market, particularly important bookplates can dramatically raise the value of volumes, and books that have always remained in private hands rather than in institutions and are accompanied by a well-documented provenance, which may include evidence drawn from bookplates, are particularly desirable for collectors.

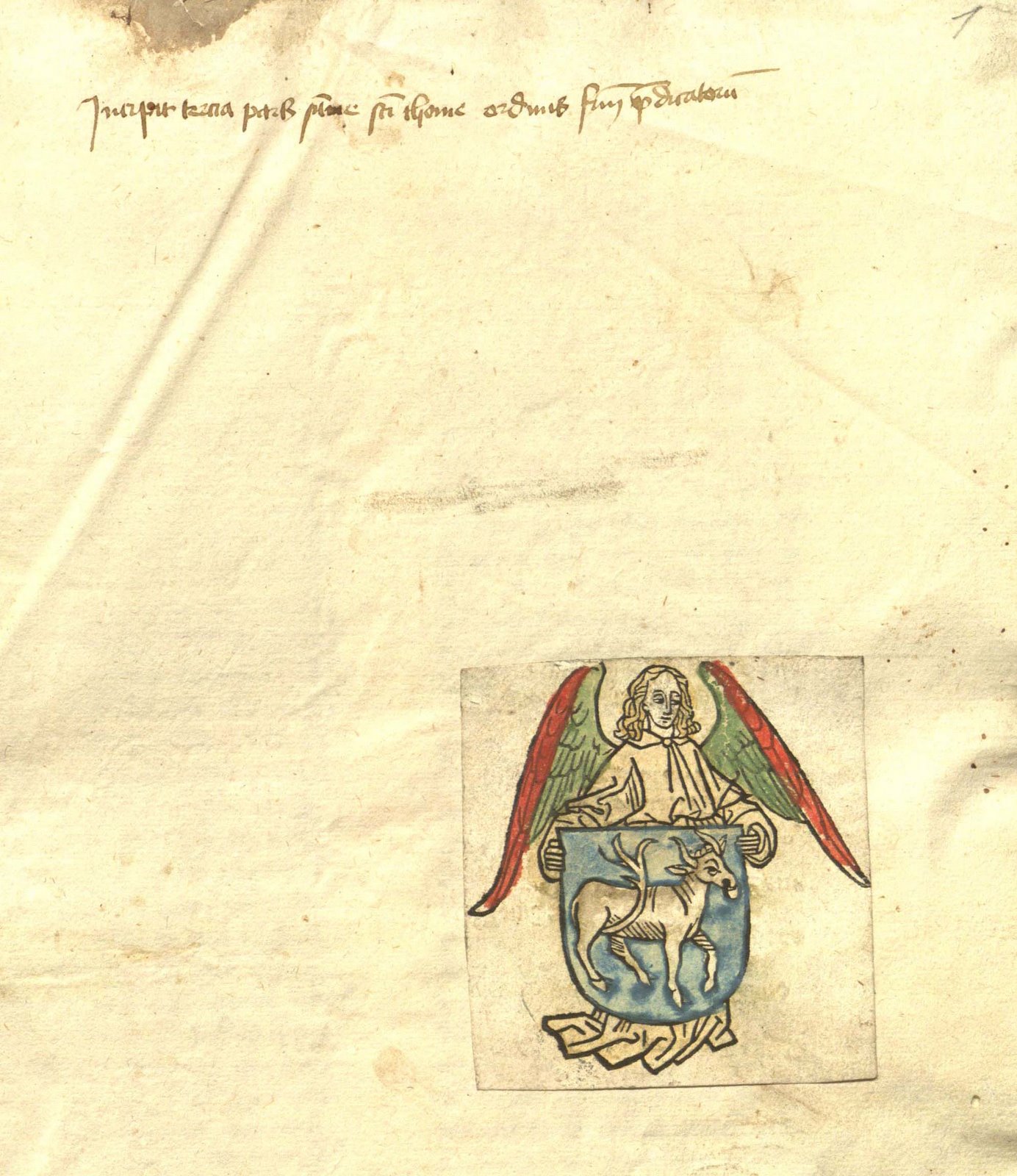

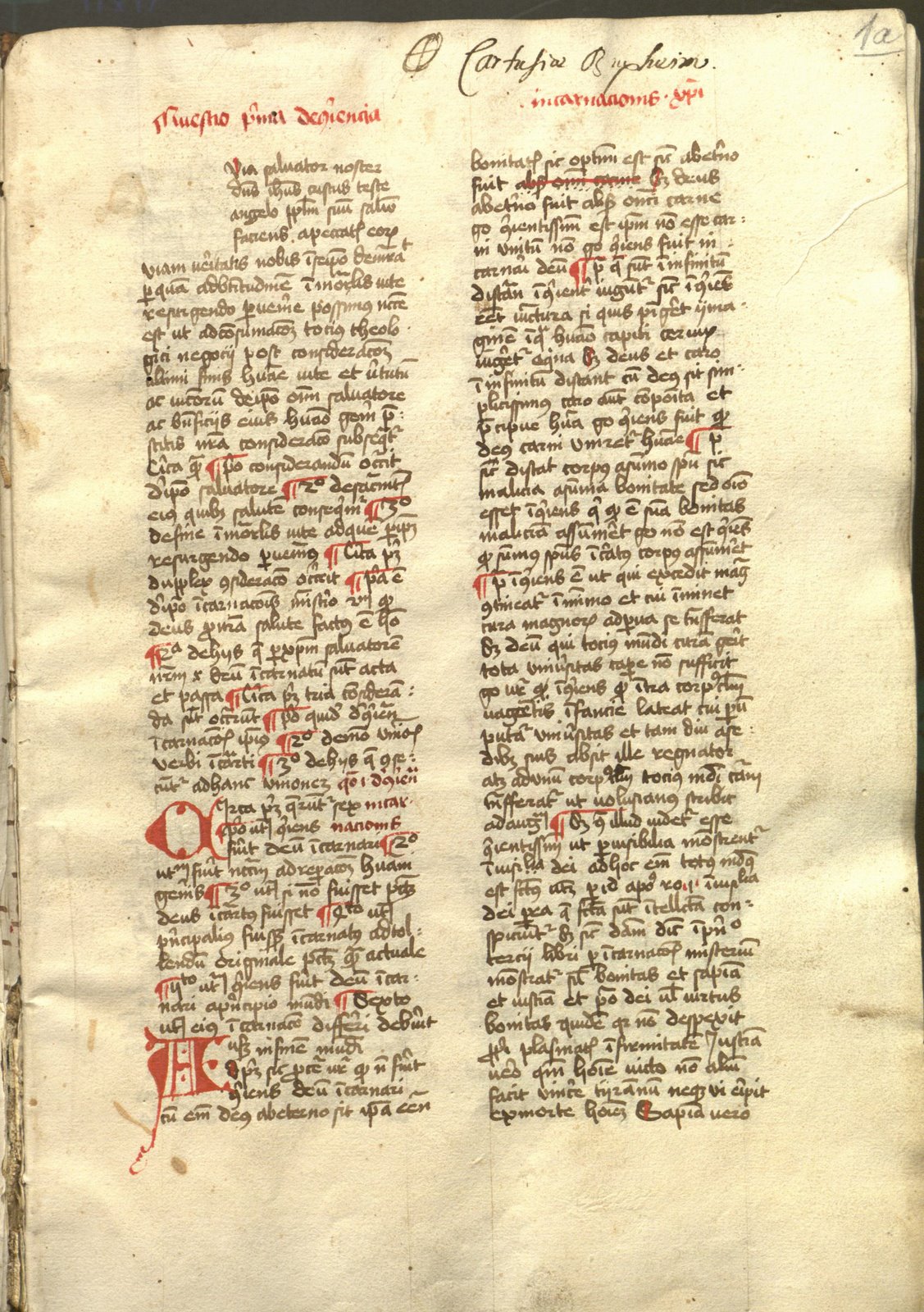

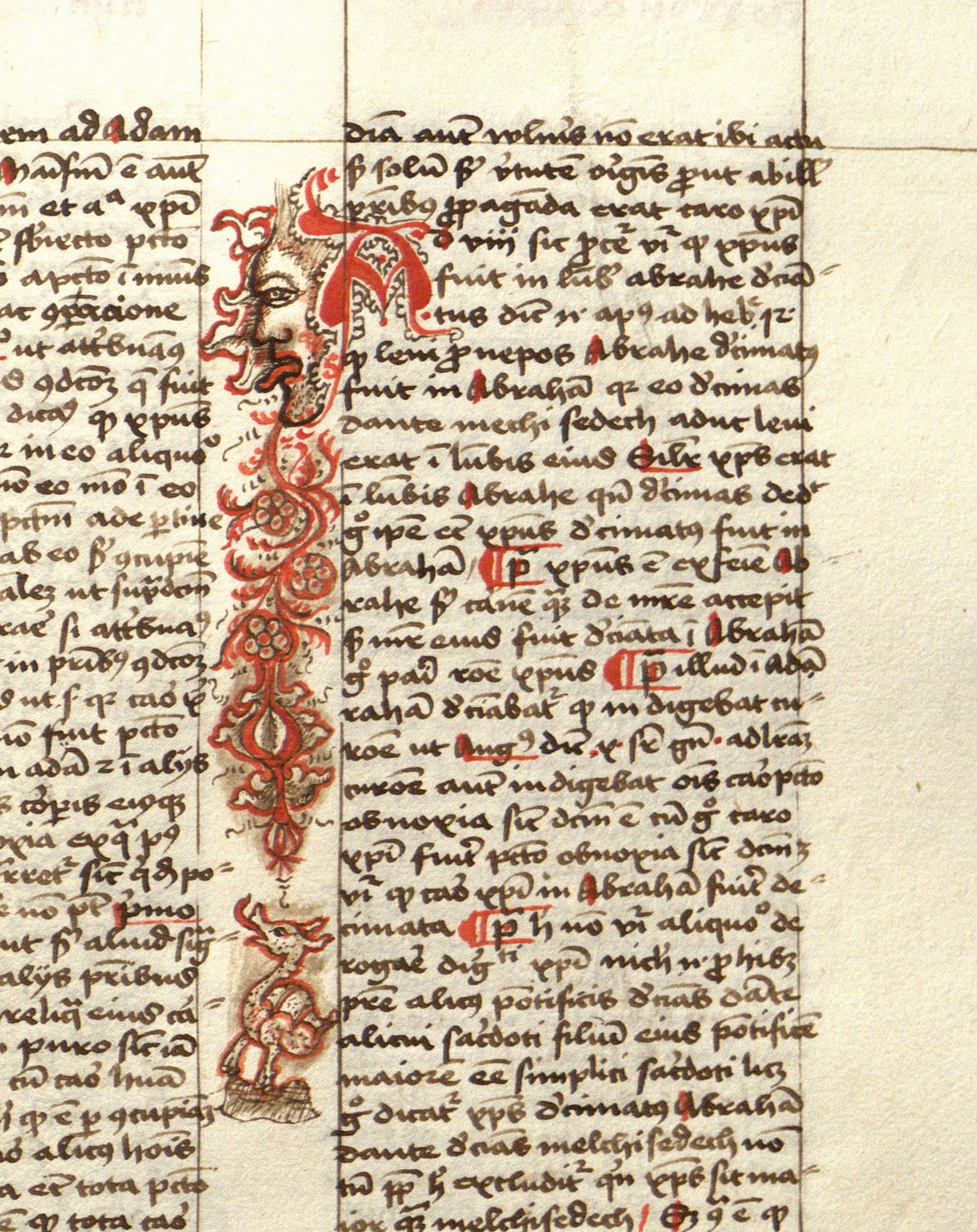

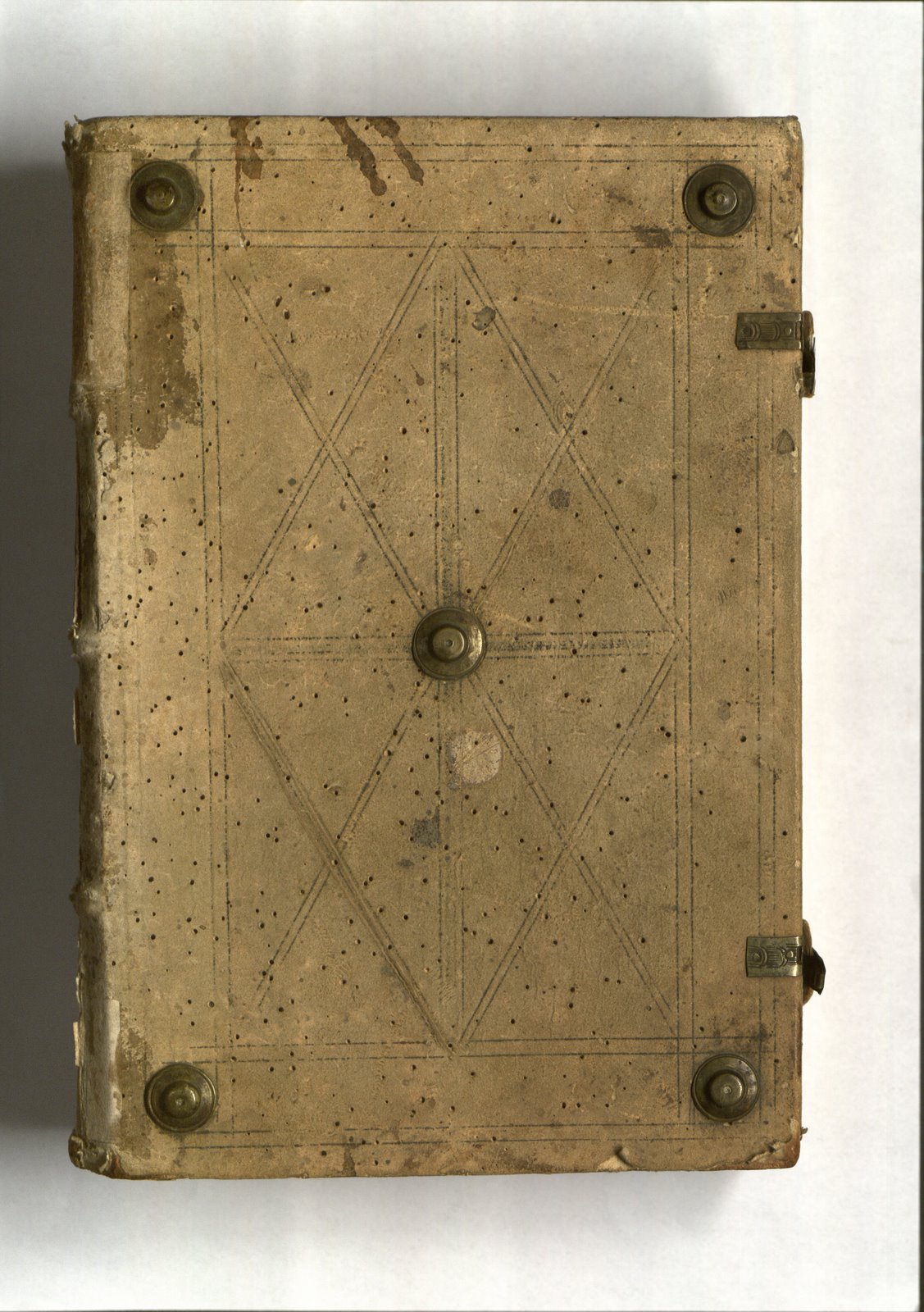

With a famous plate such as that of Hildebrand of Biberach, it is possible to trace the history of the volume nearly from the time of its composition. Our copy of this bookplate is found in a manuscript of Part III of the Summa theologica of Thomas Aquinas, one of the most important texts of the medieval period. This large folio volume (32 x 22 cm.) contains 157 paper leaves with the text written in two columns in a single cursive gothic hand. It is ruled in lead, with running titles and chapter headings, and contains moderate abbreviation and rubrication throughout. The decoration of the manuscript is fairly undistinguished except for a single large historiated initial containing a man’s face, floral decoration and a dragon on f. 85r. The text is bound in its original doeskin (sheepskin?) binding over oak boards, with a vellum label and manuscript title on the spine and brass bosses present on the front and rear covers, along with intact vellum straps with brass hardware. Three of the original bosses are now missing, and there is some significant worm damage to the cover, which is common in doeskin bindings.

With a famous plate such as that of Hildebrand of Biberach, it is possible to trace the history of the volume nearly from the time of its composition. Our copy of this bookplate is found in a manuscript of Part III of the Summa theologica of Thomas Aquinas, one of the most important texts of the medieval period. This large folio volume (32 x 22 cm.) contains 157 paper leaves with the text written in two columns in a single cursive gothic hand. It is ruled in lead, with running titles and chapter headings, and contains moderate abbreviation and rubrication throughout. The decoration of the manuscript is fairly undistinguished except for a single large historiated initial containing a man’s face, floral decoration and a dragon on f. 85r. The text is bound in its original doeskin (sheepskin?) binding over oak boards, with a vellum label and manuscript title on the spine and brass bosses present on the front and rear covers, along with intact vellum straps with brass hardware. Three of the original bosses are now missing, and there is some significant worm damage to the cover, which is common in doeskin bindings.

The manuscript was composed around 1460, and thus Hildebrand or Hilpbrand Brandenburg of Biberach was likely its original owner. From the wealthy Brandenburg family, Hildebrand was a Carthusian monk in a monastery near Buxheim, Germany, who, around the year 1480, donated a number of books, including this one, to the monastery library. Accompanying the donation, in each volume Hildebrand pasted a bookplate or gift plate that indicates him as the donor of the book. It depicts an angel bearing a shield, which displays the Brandenburg crest, “azure charged with an ox argent, ringed sable,” as Egerton Castle describes it in English Bookplates (33). These plates are wood-block prints that he then colored by hand, and in many texts they are accompanied by a short inscription by Hildebrand identifying the contents of the volume.

The manuscript was composed around 1460, and thus Hildebrand or Hilpbrand Brandenburg of Biberach was likely its original owner. From the wealthy Brandenburg family, Hildebrand was a Carthusian monk in a monastery near Buxheim, Germany, who, around the year 1480, donated a number of books, including this one, to the monastery library. Accompanying the donation, in each volume Hildebrand pasted a bookplate or gift plate that indicates him as the donor of the book. It depicts an angel bearing a shield, which displays the Brandenburg crest, “azure charged with an ox argent, ringed sable,” as Egerton Castle describes it in English Bookplates (33). These plates are wood-block prints that he then colored by hand, and in many texts they are accompanied by a short inscription by Hildebrand identifying the contents of the volume.

Much of the life of the manuscript was thus spent in the hands of the Carthusians, for the monastery at Buxheim held the manuscript until the sale of its collection in 1883, more than 400 years after the original donation. This small and austere order is often recognized as being the most rigorous in the Roman Catholic tradition. Carthusian monks discern a particular vocation or charism for solitude, and while living as part of a monastic community, a brother “will pass the greater part of his life in his cell where he prays, works, takes his meals and sleeps,” except at appointed times when he joins the community in praying the divine office or celebrating a communal mass.[1] This solitude is compounded by a vow of silence, such that the brothers speak to one another only at meals and on occasional walks outside of the cloister. There is no television or radio in the monastery, and no visitors are permitted, other than close family members of the brothers, who may come on set days twice a year. The recent highly-acclaimed film Into Great Silence chronicles the lives of the monks of the great monastery of the Carthusians, La Grande Chartreuse, high in the French Alps, where the order was founded in 1084.[2] (Connoisseurs of fine liqueurs may also recognize this monastery as the source of Chartreuse, a spirit distilled from over 130 herbs and flowers, whose early-17th-century recipe is a closely guarded secret, known only to three of the monks at any given time; the sale of this liqueur provides a major source of support for the order.)

Much of the life of the manuscript was thus spent in the hands of the Carthusians, for the monastery at Buxheim held the manuscript until the sale of its collection in 1883, more than 400 years after the original donation. This small and austere order is often recognized as being the most rigorous in the Roman Catholic tradition. Carthusian monks discern a particular vocation or charism for solitude, and while living as part of a monastic community, a brother “will pass the greater part of his life in his cell where he prays, works, takes his meals and sleeps,” except at appointed times when he joins the community in praying the divine office or celebrating a communal mass.[1] This solitude is compounded by a vow of silence, such that the brothers speak to one another only at meals and on occasional walks outside of the cloister. There is no television or radio in the monastery, and no visitors are permitted, other than close family members of the brothers, who may come on set days twice a year. The recent highly-acclaimed film Into Great Silence chronicles the lives of the monks of the great monastery of the Carthusians, La Grande Chartreuse, high in the French Alps, where the order was founded in 1084.[2] (Connoisseurs of fine liqueurs may also recognize this monastery as the source of Chartreuse, a spirit distilled from over 130 herbs and flowers, whose early-17th-century recipe is a closely guarded secret, known only to three of the monks at any given time; the sale of this liqueur provides a major source of support for the order.)

As the original owner of this manuscript and the creator of its bookplate was a Carthusian, the laborious task of hand-coloring each bookplate and writing a description of each volume on the front flyleaf takes on a new light in the context of his monastic vocation. The monastery at Buxheim was an important and influential center of learning in the Carthusian order, and its library became renowned. Several partial lists of the library contents from various time periods are extant, and a recent project sponsored by Yale University is currently attempting to recreate the library in digital form, with links provided to each volume from the collection. The Buxheim shelfmark, number 144, which functioned like a call number to denote this book’s place in the library, is still visible in red at the base of the spine of the manuscript. Its actual location on the shelf at Buxheim is depicted as part of the Yale project. Yale dean and bibliographer William Whobrey, who directs this project, goes so far as to argue that the influence of Hildebrand’s famous bookplate from Buxheim may be seen in the angel that guards the entry to the Arts of the Book collection in Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library.[3]

As the original owner of this manuscript and the creator of its bookplate was a Carthusian, the laborious task of hand-coloring each bookplate and writing a description of each volume on the front flyleaf takes on a new light in the context of his monastic vocation. The monastery at Buxheim was an important and influential center of learning in the Carthusian order, and its library became renowned. Several partial lists of the library contents from various time periods are extant, and a recent project sponsored by Yale University is currently attempting to recreate the library in digital form, with links provided to each volume from the collection. The Buxheim shelfmark, number 144, which functioned like a call number to denote this book’s place in the library, is still visible in red at the base of the spine of the manuscript. Its actual location on the shelf at Buxheim is depicted as part of the Yale project. Yale dean and bibliographer William Whobrey, who directs this project, goes so far as to argue that the influence of Hildebrand’s famous bookplate from Buxheim may be seen in the angel that guards the entry to the Arts of the Book collection in Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library.[3]

While the library at Buxheim provides several important examples of very early bookplates of the late medieval and Renaissance periods, including the Hildebrand plate, the use and importance of bookplates is by no means confined to the early years of printing, but continues to the present day, as new designs constantly grace institutional and personal collections. The Brandeis Library places a simple plate with the Brandeis seal (a gesture, perhaps, to the noble armorial origins of the bookplate) accompanied by a quote by Rashi in each volume it purchases, and students and faculty at the university have quite likely come across this plate in their reading. Those who donate books to the university have the option of including an individualized bookplate in those volumes, which can range from a simple acknowledgement of a gift or a dedication in honor of a family member or friend to elaborate personalized gift plates for important collections—the modern equivalent of Hildebrand’s first plate, which accompanied the donation of his collection to his monastery.

While the library at Buxheim provides several important examples of very early bookplates of the late medieval and Renaissance periods, including the Hildebrand plate, the use and importance of bookplates is by no means confined to the early years of printing, but continues to the present day, as new designs constantly grace institutional and personal collections. The Brandeis Library places a simple plate with the Brandeis seal (a gesture, perhaps, to the noble armorial origins of the bookplate) accompanied by a quote by Rashi in each volume it purchases, and students and faculty at the university have quite likely come across this plate in their reading. Those who donate books to the university have the option of including an individualized bookplate in those volumes, which can range from a simple acknowledgement of a gift or a dedication in honor of a family member or friend to elaborate personalized gift plates for important collections—the modern equivalent of Hildebrand’s first plate, which accompanied the donation of his collection to his monastery.

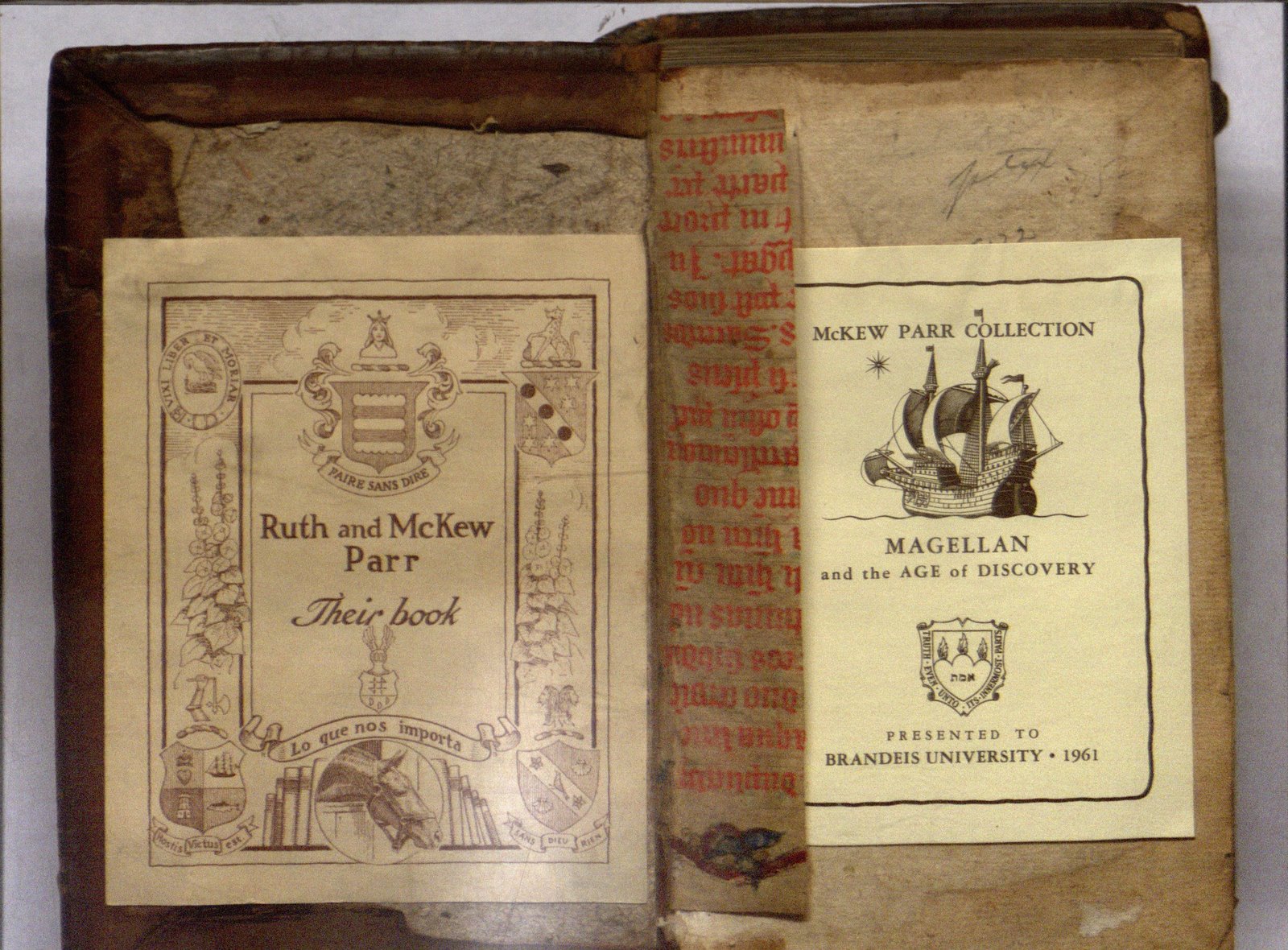

Several of these are quite striking, including that of Charles and Ruth McKew Parr. In one example, from a history of Mexico published in 1554, the McKew Parr personal bookplate appears on the left, pasted inside the front cover, while opposite, on the front flyleaf, is the gift plate recording the presentation of the collection to Brandeis University. Also visible along the hinge is a 13th-century manuscript fragment that has been used to reinforce the binding.

Several of these are quite striking, including that of Charles and Ruth McKew Parr. In one example, from a history of Mexico published in 1554, the McKew Parr personal bookplate appears on the left, pasted inside the front cover, while opposite, on the front flyleaf, is the gift plate recording the presentation of the collection to Brandeis University. Also visible along the hinge is a 13th-century manuscript fragment that has been used to reinforce the binding.

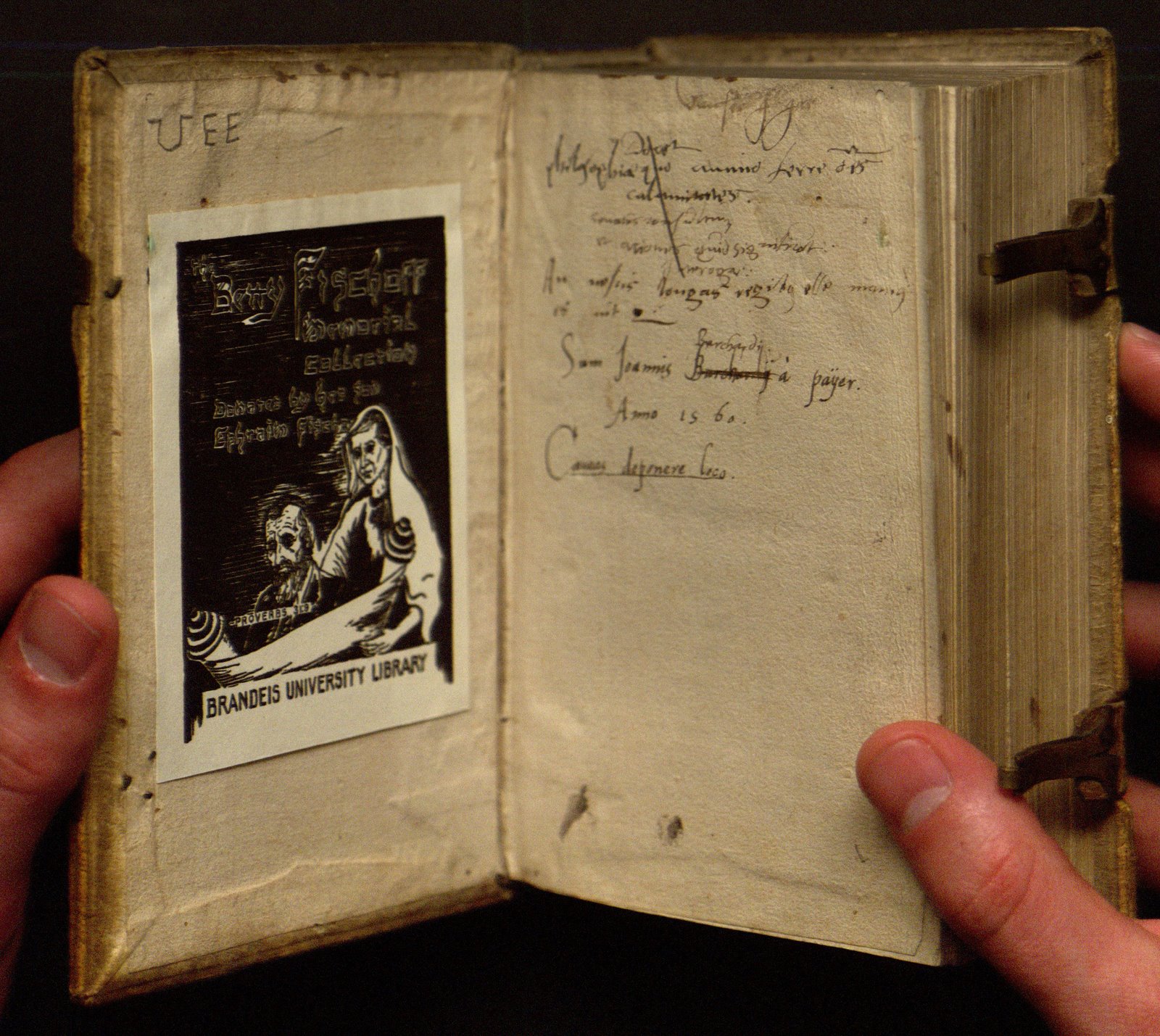

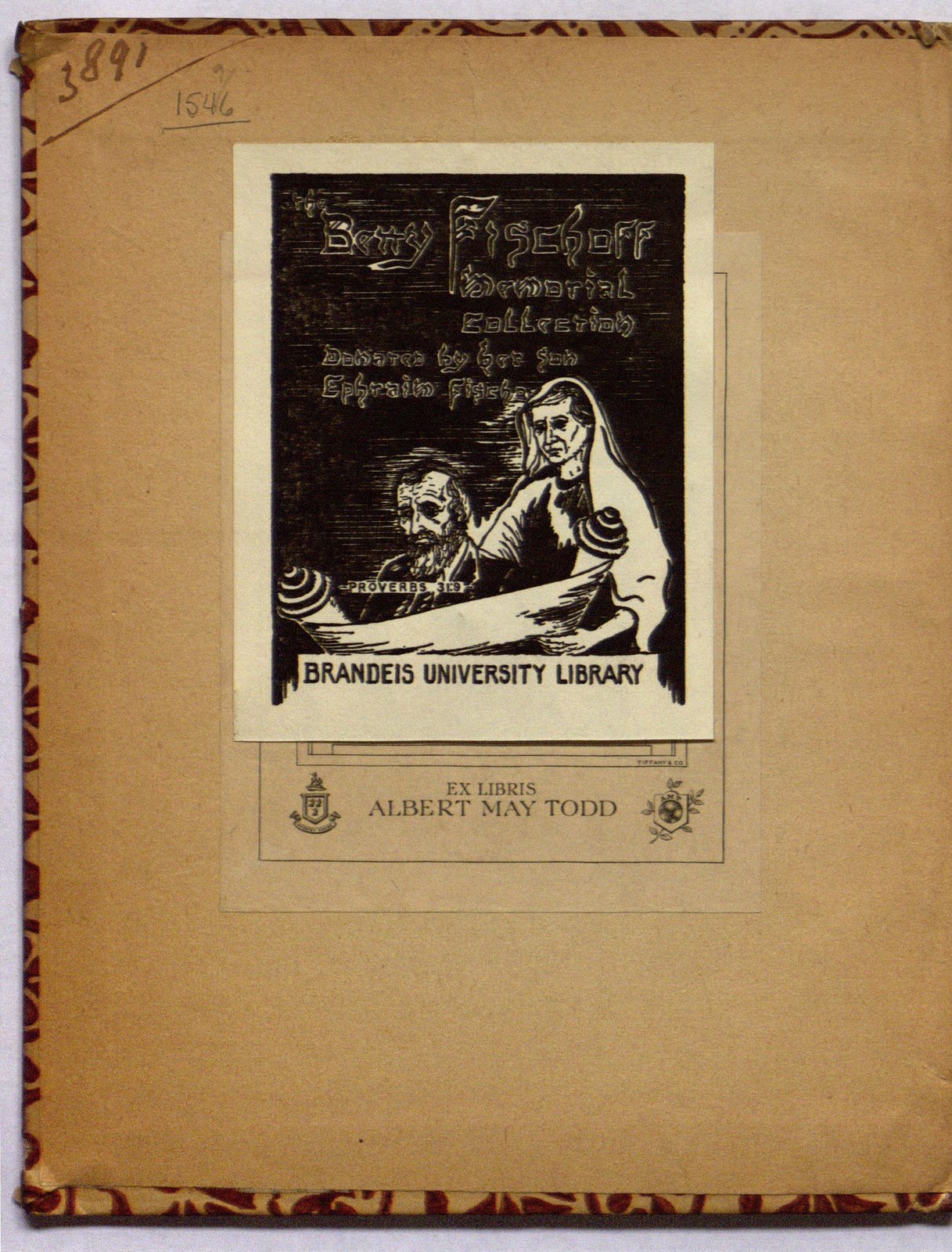

The Fischoff collection also has a very distinctive bookplate that marks the donation of Betty Fischoff’s collection by her son Ephraim to the Brandeis library. As you can see in this example, this plate has been pasted in over an earlier bookplate, an ex libris that records this volume as once part of the collection of Albert May Todd. In another Fischoff book, her plate is present opposite the inscription of an early owner, which reads Sum Joannis Burchardii a payer(?) / Anno 1560 (“I am Johann Burchard…”) followed by the injuction Caveas deponere loco, which, loosely translated, means, “Beware of taking this book from this place.”

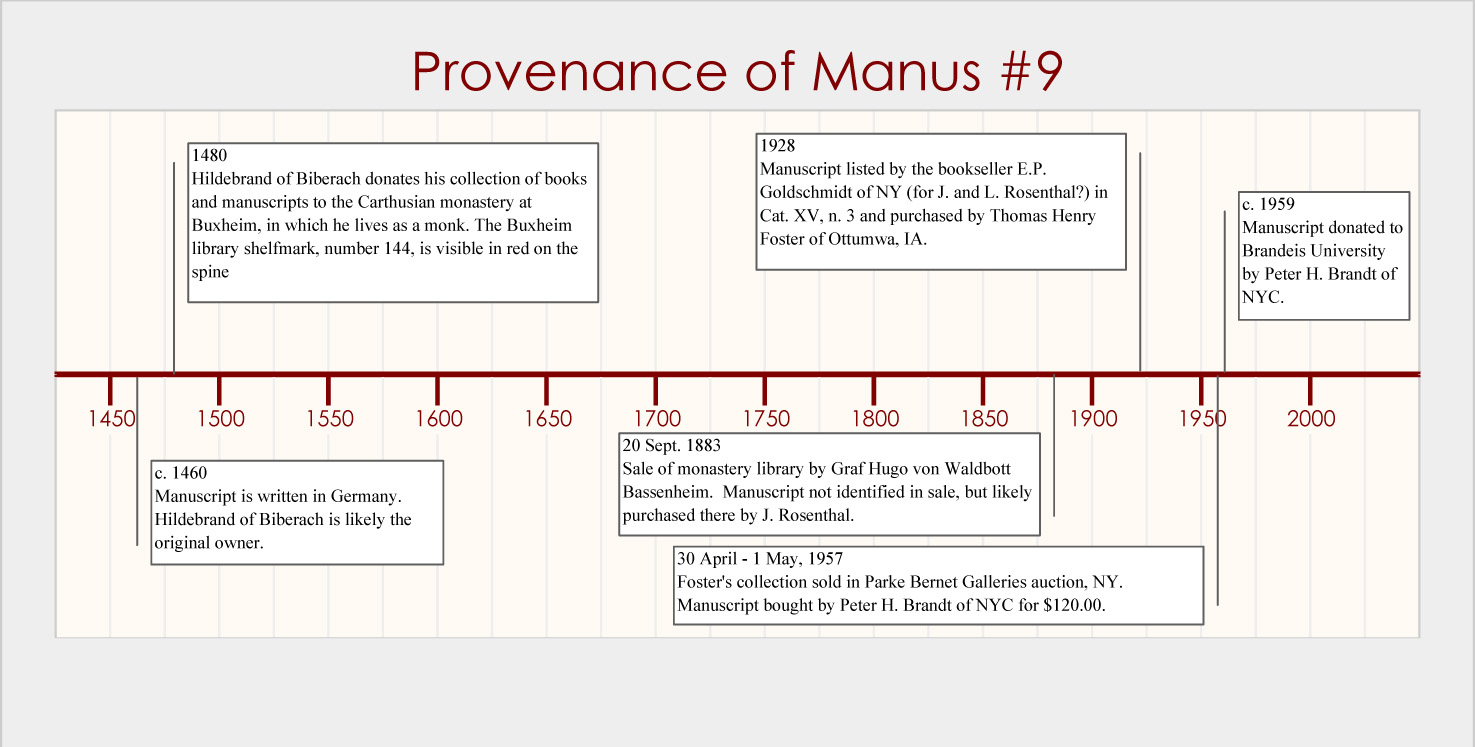

On some occasions, it is possible to compile the full history of a very old manuscript, and the Thomas Aquinas manuscript once owned by Hildebrand of Biberach is one of those rare examples where a complete record of the provenance exists. Tracing a book through the centuries gives some idea of its continual importance—as a valuable piece of scholarship, as an important religious text, as an historical artifact, as a work of art and finally, as a resource for students and scholars, particularly in the Brandeis community, who represent the next entry in the long history of this manuscript.

On some occasions, it is possible to compile the full history of a very old manuscript, and the Thomas Aquinas manuscript once owned by Hildebrand of Biberach is one of those rare examples where a complete record of the provenance exists. Tracing a book through the centuries gives some idea of its continual importance—as a valuable piece of scholarship, as an important religious text, as an historical artifact, as a work of art and finally, as a resource for students and scholars, particularly in the Brandeis community, who represent the next entry in the long history of this manuscript.

Specifications

Language: Latin.

Date: c. 1460.

Title: Summa Theologica : Pars Tertia ; incipit: Questio p[ri]ma de c[onveni]entia incarnationis.

Creator: Aquinas, Thomas, Saint ; Unknown.

Place of creation: Germany.

Physical description: Paper, 157 leaves ; 32 x 22 cm.

Summary: Catholic Church theology. Part three of the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas, perhaps the single most important theological work of the later Middle Ages.

Note: Folio. Written in a single hand in a cursive gothic script ; 2 columns of varying numbers of lines (40-70) ; writing block is 220 x 64 mm. Ruled in lead ; red initials, running titles and chapter headings. One large decorated initial on f. 85 r. (a man’s face, floral decoration and a dragon) ; hand-drawn colored bookplate pasted to front free endpaper. Bound in original blind-stamped doeskin (sheepskin?) over heavy wooden boards ; vellum label and manuscript title to spine ; brass bosses and intact brass and vellum clasps to front and rear cover, 3 of original 10 bosses now missing ; some worm damage to cover (common with doeskin) ; housed in quarter leather box. Originally owned by Hildebrand or Hilpbrand Brandenburg of Biberach (c.1460-1480) ; his bookplate, the first on record, on front flyleaf : an angel bearing an escutcheon displaying the Brandenburg crest, azure charged with an ox argent, ringed sable. Gift of Hildebrand to the Carthusian monastery at Buxheim, Germany. Sold 20 Sept. 1883 in Munich by Graf Hugo von Waldbott-Bassenheim to J. Rosenthal(?) [not identified in sale]. Sale of E.P. Goldschmidt, Cat. XV, n.3 to Thomas Henry Foster of Ottumwa, IA, 1928. Foster collection sold at auction, Parke-Bernet Galleries, NY to Peter H. Brandt of NYC for $120.00, 30 April-1 May, 1957. Gift of Peter H. Brandt, c. 1959. De Ricci I, 723. Faye and Bond, 188.

Note: Folio. Written in a single hand in a cursive gothic script ; 2 columns of varying numbers of lines (40-70) ; writing block is 220 x 64 mm. Ruled in lead ; red initials, running titles and chapter headings. One large decorated initial on f. 85 r. (a man’s face, floral decoration and a dragon) ; hand-drawn colored bookplate pasted to front free endpaper. Bound in original blind-stamped doeskin (sheepskin?) over heavy wooden boards ; vellum label and manuscript title to spine ; brass bosses and intact brass and vellum clasps to front and rear cover, 3 of original 10 bosses now missing ; some worm damage to cover (common with doeskin) ; housed in quarter leather box. Originally owned by Hildebrand or Hilpbrand Brandenburg of Biberach (c.1460-1480) ; his bookplate, the first on record, on front flyleaf : an angel bearing an escutcheon displaying the Brandenburg crest, azure charged with an ox argent, ringed sable. Gift of Hildebrand to the Carthusian monastery at Buxheim, Germany. Sold 20 Sept. 1883 in Munich by Graf Hugo von Waldbott-Bassenheim to J. Rosenthal(?) [not identified in sale]. Sale of E.P. Goldschmidt, Cat. XV, n.3 to Thomas Henry Foster of Ottumwa, IA, 1928. Foster collection sold at auction, Parke-Bernet Galleries, NY to Peter H. Brandt of NYC for $120.00, 30 April-1 May, 1957. Gift of Peter H. Brandt, c. 1959. De Ricci I, 723. Faye and Bond, 188.

Former Call #: Ms. 9

Call #: Manus 9

Notes

- The Carthusian Order, website

- See the New York Times review of the movie “Into Great Silence”

- See Yale Bulletin and Calendar article