Children’s Literature Collection

March 2, 2017

Description by Jonathan Sudholt

Love it or hate it — or, display some more middle-way attitude if it pleases you — popular fiction plays an important role in society. The Brandeis Collection of Children’s Literature contains examples of the genre that date from the fin-de-siècle to the Eisenhower administration. Only four authors get detailed mention on this site, but the collection is much more extensive, including books from Henry Castelmon’s The Sportsman’s Club series, the X Bar X Boys, MacGuffey’s Reader, and Ainsworth Magazine, among others. A broader sample is available online.

Love it or hate it — or, display some more middle-way attitude if it pleases you — popular fiction plays an important role in society. The Brandeis Collection of Children’s Literature contains examples of the genre that date from the fin-de-siècle to the Eisenhower administration. Only four authors get detailed mention on this site, but the collection is much more extensive, including books from Henry Castelmon’s The Sportsman’s Club series, the X Bar X Boys, MacGuffey’s Reader, and Ainsworth Magazine, among others. A broader sample is available online.

Though often caricatured as simple rubber stamps for the dominant social values of their time, these books reflect some of the narrative challenges that come with trying to validate through myth a power structure that undermines its own myth. This is generally expressed as a problem of plotting in the novels discussed in this exhibit. One might ask how an author concludes his story of upward mobility in a satisfying way, if possessing wealth has been marked negatively throughout the story. What kinds of heroes fail in a popular novel? More specifically, what kind of hero fails in, say, a novel by Horatio Alger, who does not fail in a novel by Oliver Optic? If popular fiction serves only to reinforce the status quo, why do the novels in this collection have such different attitudes about wealth, the right way to attain it, and the right way to use it?

In making these books available to a wider audience, this exhibit hopes to encourage further discussion of popular fiction’s social function. A list of the entire collection is available via Brandeis library catalog. For those books out of copyright protection, the catalog offers links to online versions available, for free, through the Internet Archive.

A brief word about provenance: The Collection of Children's Literature is a part of the Dime Novels and Juvenile Literature Collection. The department received these materials from different sources. Large donations came from Charles and Edward Levy, Victor Berch, and Edward T. LeBlanc.

Horatio Alger

Alger’s heroes are working-class adolescent boys who, through hard work, honest dealings, and temperance, rise to live in bourgeois comfort. Herbert Carter’s Legacy (1875) follows one such boy as he struggles to make ends meet until he can overcome his financial straits. Midway through the novel, Alger writes, “To be willing to work, and yet to be unable to find an opportunity, was certainly a hardship.” And indeed, in Alger’s novels, each hero’s metaphysical crisis comes from not being able to use his able body, rather than from being without money. Alger’s villains, rascals, and knaves are pointlessly, infuriatingly wealthy, and his women are either dutiful mothers or triumphantly conscienceless manipulators. They are, in Alger’s world, non-producers. The concept of work as its own end is hardly unique to this novelist, but he does employ it in unexpected ways. In his moralization of President James A. Garfield’s life, From Canal Boy to President, he describes the future president’s introduction to the world of work, in which a farmer offers a job to his older brother, Thomas. “’I need help on my farm, and I guess you will suit me,’

Alger’s heroes are working-class adolescent boys who, through hard work, honest dealings, and temperance, rise to live in bourgeois comfort. Herbert Carter’s Legacy (1875) follows one such boy as he struggles to make ends meet until he can overcome his financial straits. Midway through the novel, Alger writes, “To be willing to work, and yet to be unable to find an opportunity, was certainly a hardship.” And indeed, in Alger’s novels, each hero’s metaphysical crisis comes from not being able to use his able body, rather than from being without money. Alger’s villains, rascals, and knaves are pointlessly, infuriatingly wealthy, and his women are either dutiful mothers or triumphantly conscienceless manipulators. They are, in Alger’s world, non-producers. The concept of work as its own end is hardly unique to this novelist, but he does employ it in unexpected ways. In his moralization of President James A. Garfield’s life, From Canal Boy to President, he describes the future president’s introduction to the world of work, in which a farmer offers a job to his older brother, Thomas. “’I need help on my farm, and I guess you will suit me,’  said Mr. Conrad, though that was not his name. In fact, I don’t know his name, but that will do as well as any other” (page 12). Later, Alger writes that the meeting with Mr. Conrad did not happen at all, and that he will henceforth follow the narrative provided by Edmund Kirke. But in turning to a more reliable history, he does not invalidate the fiction that he has now admitted is fiction. That is the power of work. It is so exciting an idea that facts are secondary.

said Mr. Conrad, though that was not his name. In fact, I don’t know his name, but that will do as well as any other” (page 12). Later, Alger writes that the meeting with Mr. Conrad did not happen at all, and that he will henceforth follow the narrative provided by Edmund Kirke. But in turning to a more reliable history, he does not invalidate the fiction that he has now admitted is fiction. That is the power of work. It is so exciting an idea that facts are secondary.

Oliver Optic

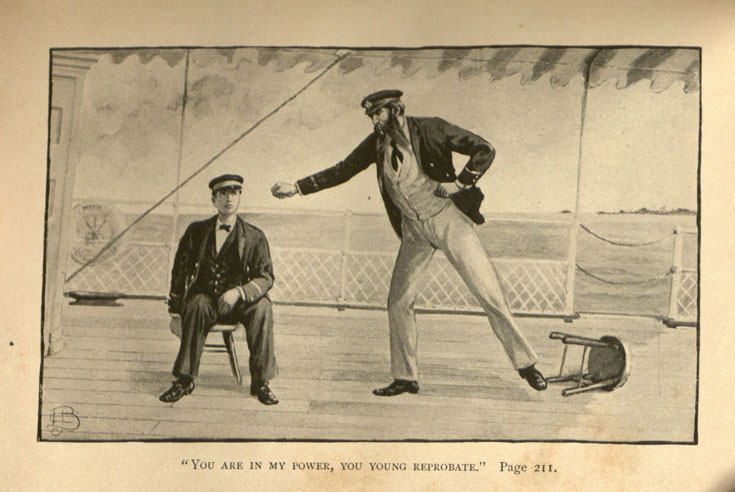

Oliver Optic’s heroes are often allowed to enjoy their financial security. His “All Over the World Library” (1892–1898) follows the heroically wealthy Louis Belgrave, whose adventures depend upon his wealth. Optic acknowledges his debt to Belgrave’s assets in the preface to the second book in the series, A Millionaire at Sixteen (1892), by writing, “Possibly some of my numerous friends may have accused me, after reading the first volume [A Missing Million (1892)], with being unnecessarily liberal to my hero, in supplying him with ‘the missing million,’ even augmented to nearly half as much more, so that he is actually a millionaire and a half; but the present story will assure such critics that even this vast sum was necessary in carrying out the purposes of the writer.” Louis Belgrave would be a smug, obnoxious rich boy in an Alger novel, but Optic caresses him through such difficulties as almost losing some money, very nearly being sued, and having no choice but to shoot a penurious rapscallion in the shoulder. Optic’s novels take comfort in noblesse oblige, even when the results are more complicated than strictly noble.

Oliver Optic’s heroes are often allowed to enjoy their financial security. His “All Over the World Library” (1892–1898) follows the heroically wealthy Louis Belgrave, whose adventures depend upon his wealth. Optic acknowledges his debt to Belgrave’s assets in the preface to the second book in the series, A Millionaire at Sixteen (1892), by writing, “Possibly some of my numerous friends may have accused me, after reading the first volume [A Missing Million (1892)], with being unnecessarily liberal to my hero, in supplying him with ‘the missing million,’ even augmented to nearly half as much more, so that he is actually a millionaire and a half; but the present story will assure such critics that even this vast sum was necessary in carrying out the purposes of the writer.” Louis Belgrave would be a smug, obnoxious rich boy in an Alger novel, but Optic caresses him through such difficulties as almost losing some money, very nearly being sued, and having no choice but to shoot a penurious rapscallion in the shoulder. Optic’s novels take comfort in noblesse oblige, even when the results are more complicated than strictly noble.

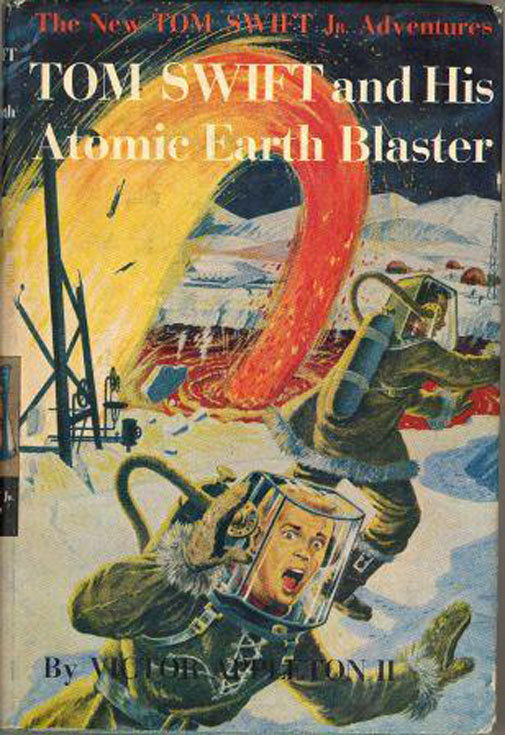

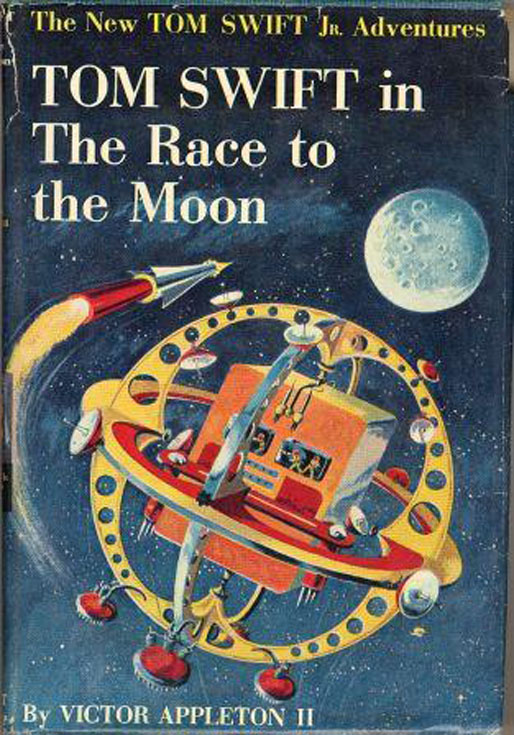

Tom Swift, Jr. by Victor Appleman, Jr.

In Tom Swift, Jr., Victor Appleton, Jr., adds an Eisenhower-era spin to the problem of heroes and money. Swift is an eighteen-year-old inventor-patriot who uses his talents to outfox suggestively-named enemies like the Brungarians and Kranjovians. He decodes a message from outer space in a couple of days, builds an atmosphere spreader (for putting atmosphere where it isn’t) overnight, and troubleshoots a faulty repelatron (his replacement for rocket power) the afternoon before he uses it to fly to the moon. Naturally, he is rewarded for his brilliance with wealth (his father, Tom Swift, Sr., owns an island, about twenty jets, and, if my geography is correct, most of the northern seaboard), but Appleton has a different challenge from either Optic’s or Alger’s: wealth or no wealth, Tom must be middle-class. Appleton therefore introduces red herring villains — American men who have inherited more wealth than Tom and his father have earned — who function as safety valves for the anti-upper-class bias.

In Tom Swift, Jr., Victor Appleton, Jr., adds an Eisenhower-era spin to the problem of heroes and money. Swift is an eighteen-year-old inventor-patriot who uses his talents to outfox suggestively-named enemies like the Brungarians and Kranjovians. He decodes a message from outer space in a couple of days, builds an atmosphere spreader (for putting atmosphere where it isn’t) overnight, and troubleshoots a faulty repelatron (his replacement for rocket power) the afternoon before he uses it to fly to the moon. Naturally, he is rewarded for his brilliance with wealth (his father, Tom Swift, Sr., owns an island, about twenty jets, and, if my geography is correct, most of the northern seaboard), but Appleton has a different challenge from either Optic’s or Alger’s: wealth or no wealth, Tom must be middle-class. Appleton therefore introduces red herring villains — American men who have inherited more wealth than Tom and his father have earned — who function as safety valves for the anti-upper-class bias.  This, then, provides Tom with competitors who, as the sad end of the aristocratic tradition, cannot compete with him. The stories follow him from one success to the next, building suspense not from danger and the threat of violence, but from anticipation about Tom’s next great achievement. But all this success has a noticeable downside for the hero. When, through circumstances beyond his control, he cannot invent, troubleshoot, or produce the next great thing, he gets bored. In Tom Swift, Jr. and the Race to the Moon (1958), he and his best bud, Bud, find themselves marooned in space, with no hope of being found before their oxygen runs out. What is the great problem they face in the interim? How to pass the time. Death by asphyxiation-in-a-few-hours is terribly dull, and it takes all of his formidable imagination to come up with jokes that will get them through it. Unfortunately, we don’t know what any of those jokes are, as the efficient Appleton deals with the entire drama with the following few lines:

This, then, provides Tom with competitors who, as the sad end of the aristocratic tradition, cannot compete with him. The stories follow him from one success to the next, building suspense not from danger and the threat of violence, but from anticipation about Tom’s next great achievement. But all this success has a noticeable downside for the hero. When, through circumstances beyond his control, he cannot invent, troubleshoot, or produce the next great thing, he gets bored. In Tom Swift, Jr. and the Race to the Moon (1958), he and his best bud, Bud, find themselves marooned in space, with no hope of being found before their oxygen runs out. What is the great problem they face in the interim? How to pass the time. Death by asphyxiation-in-a-few-hours is terribly dull, and it takes all of his formidable imagination to come up with jokes that will get them through it. Unfortunately, we don’t know what any of those jokes are, as the efficient Appleton deals with the entire drama with the following few lines:

Time dragged by. Tom and Bud swapped jokes and chattered away to keep up their spirits. From time to time they sipped at their liquid ration, which was the only way of taking nourishment inside the bulky space suits and helmets. Hope waned as their air supply grew stale and sluggish. The two boys lapsed into gloomy silence. It was broken as Bud suddenly cried out: “Tom! A rocket!”

Tom’s adventures triumph over boredom as easily as he triumphs over all that is not as American as apple pie, and teach the hard-earned lesson that the only real threat to happiness is not being able to invent.

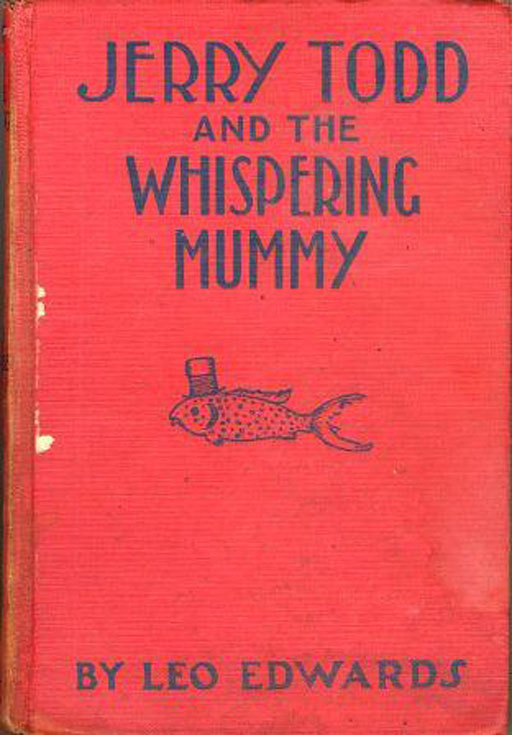

Jerry Todd, by Leo Edwards

The eponymous hero of the Jerry Todd stories (1924–1938) is safely middle-class. His creator, Leo Edwards, is therefore free from the rhetorical problem of a hero with too much money, and can focus all his energies on overcoming boredom. He even manages to give some depth to his characters. Though Jerry Todd and his friends are earnest and well-meaning, they are also irresponsible. And though the novels toe the respect-your-elders-and-love-your-country line, they are not so stuffily orthodox that the authority figures cannot have faults or errors in judgment, or cannot look, at times, a little foolish.  When, for example, Officer Bill Hadley misses his wedding because he’s been knocked unconscious and placed, handcuffed, on a train to the next town by Jerry and the gang — whose overzealous attempts to validate themselves as Junior Jupiter detectives do more to move the plot along than solve the mysteries they investigate — he returns to town with a story of how he fought off upwards of twenty strong men.

When, for example, Officer Bill Hadley misses his wedding because he’s been knocked unconscious and placed, handcuffed, on a train to the next town by Jerry and the gang — whose overzealous attempts to validate themselves as Junior Jupiter detectives do more to move the plot along than solve the mysteries they investigate — he returns to town with a story of how he fought off upwards of twenty strong men.