Helmut Hirsch Collection

February 27, 2009

Description by Karen Adler Abramson, Associate Director for University Archives and Special Collections

Brandeis University houses a number of special collections that focus on anti-Semitism, Jewish resistance to persecution and radical social movements in the United States and Europe. One such collection is the Helmut Hirsch Collection, donated to Brandeis by Hirsch’s surviving sister, Kaete “Katie” Hirsch Sugarman. Comprised of correspondence, notebooks, diaries, artwork, poetry and other writings, photographic scrapbooks and memorial publications, the collection documents the life and trials of a young German Jew who opposed the Nazi regime during the 1930s. Helmut “Helle” Hirsch (1916-1937) was a German Jewish youth executed by the Nazis on June 4, 1937. While the facts surrounding the case remain murky—Hirsch was tried and convicted in secret—what is known is that Helmut Hirsch was involved in a plot to bomb the Nazi headquarters at Nuremberg and possibly the office or printing plant of Der Stürmer, a German anti-Semitic newspaper.

Brandeis University houses a number of special collections that focus on anti-Semitism, Jewish resistance to persecution and radical social movements in the United States and Europe. One such collection is the Helmut Hirsch Collection, donated to Brandeis by Hirsch’s surviving sister, Kaete “Katie” Hirsch Sugarman. Comprised of correspondence, notebooks, diaries, artwork, poetry and other writings, photographic scrapbooks and memorial publications, the collection documents the life and trials of a young German Jew who opposed the Nazi regime during the 1930s. Helmut “Helle” Hirsch (1916-1937) was a German Jewish youth executed by the Nazis on June 4, 1937. While the facts surrounding the case remain murky—Hirsch was tried and convicted in secret—what is known is that Helmut Hirsch was involved in a plot to bomb the Nazi headquarters at Nuremberg and possibly the office or printing plant of Der Stürmer, a German anti-Semitic newspaper.

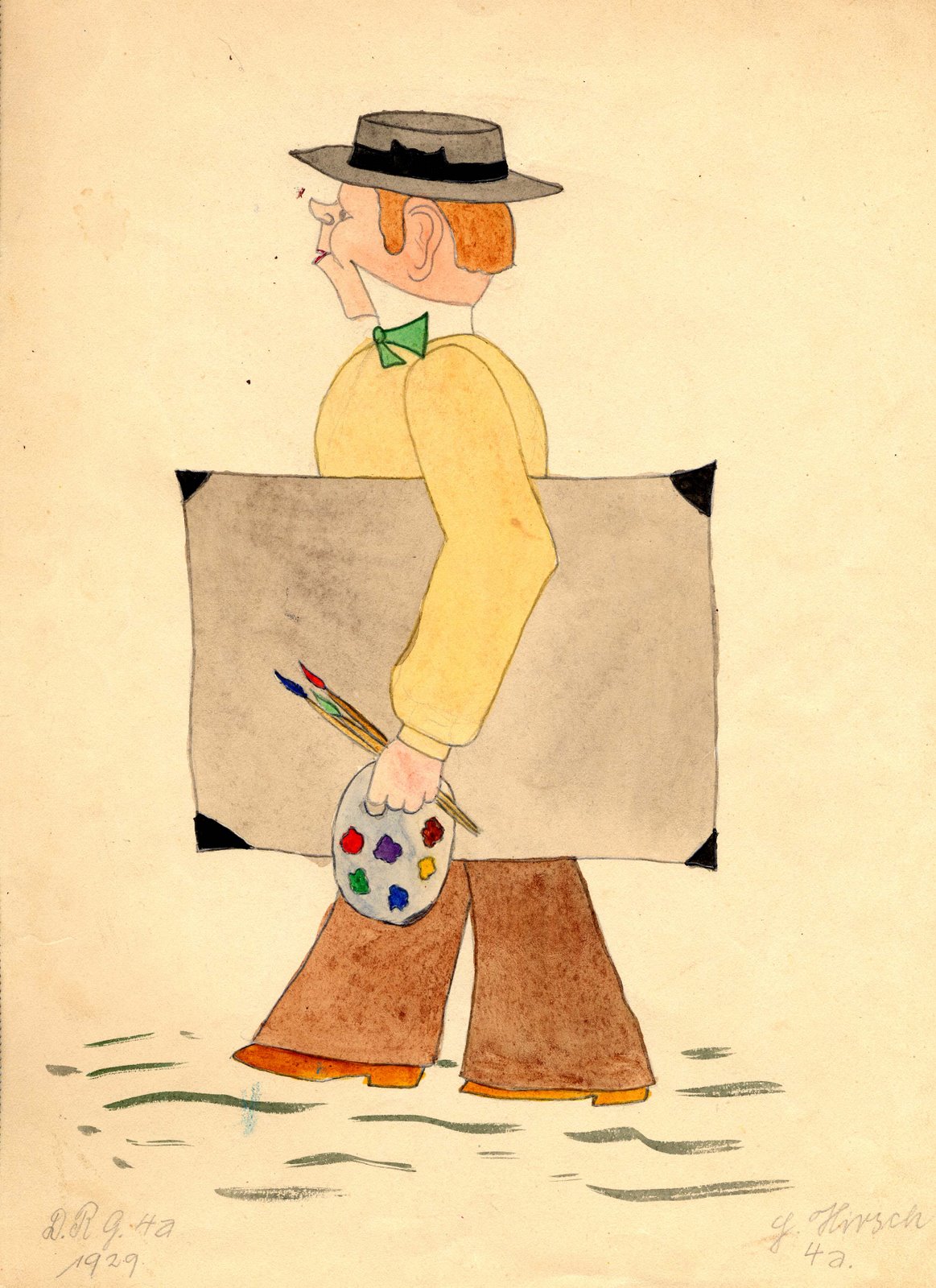

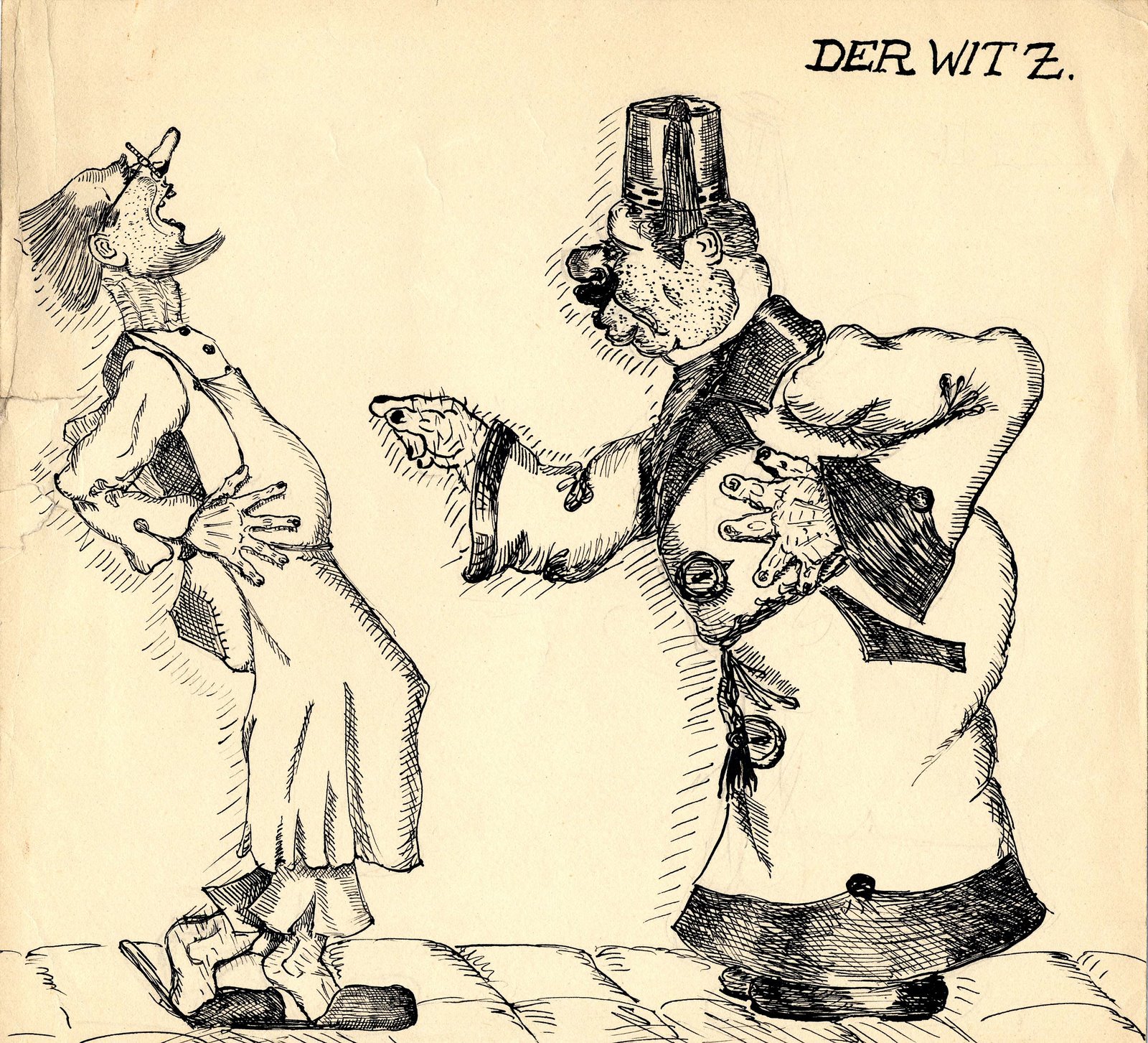

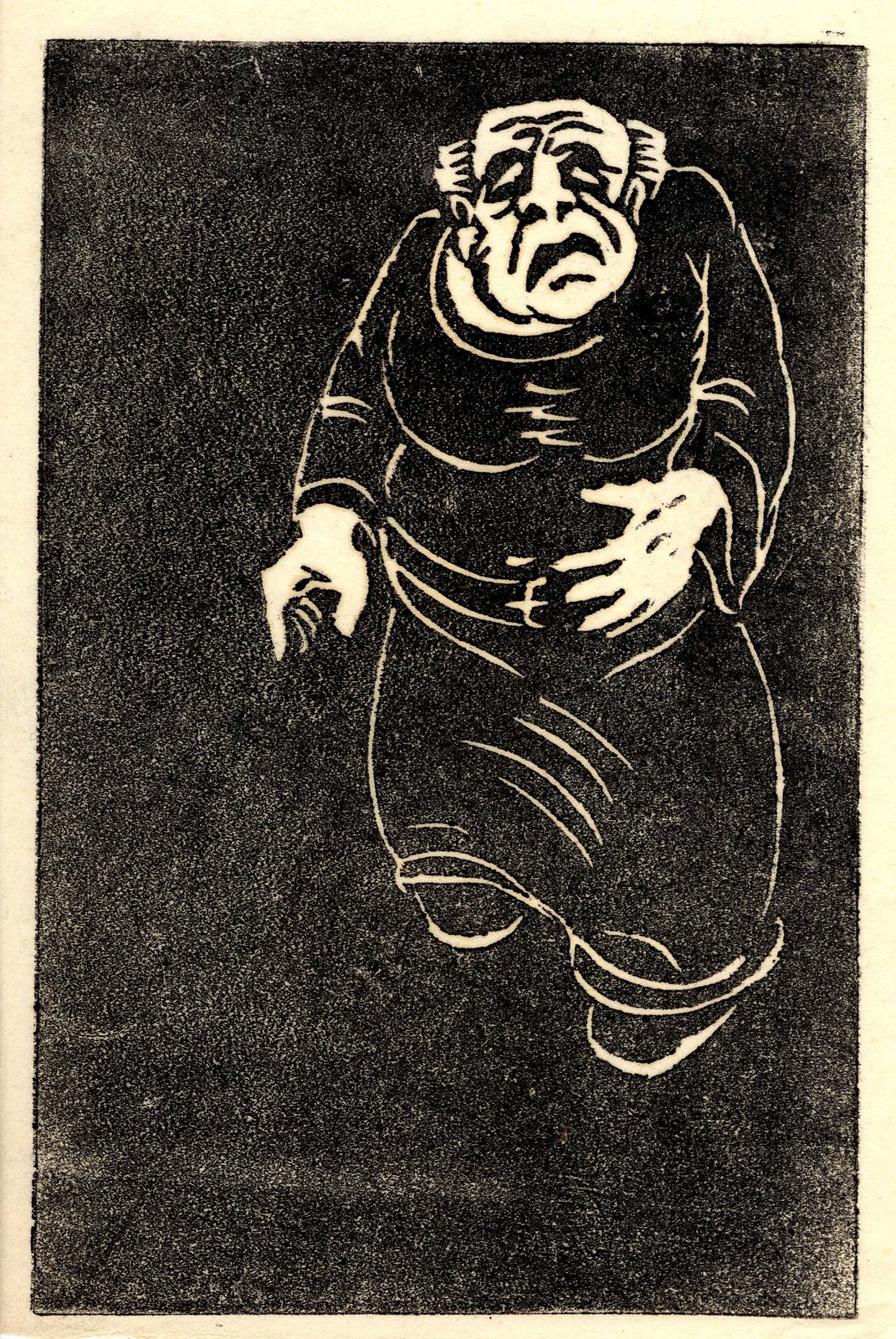

Born and raised in Stuttgart, Germany, Helmut Hirsch was the elder child of Marta Neuburger Hirsch and Siegfried Hirsch; his sister, Kaete, was one year younger. Hirsch demonstrated a precocious creativity at a young age and he was an excellent artist and draughtsman; included in his collection are sketches, paintings, ink drawings, paper cutouts, block prints, comic strips, illustrated poems and art books that he produced as a child and adolescent.

Born and raised in Stuttgart, Germany, Helmut Hirsch was the elder child of Marta Neuburger Hirsch and Siegfried Hirsch; his sister, Kaete, was one year younger. Hirsch demonstrated a precocious creativity at a young age and he was an excellent artist and draughtsman; included in his collection are sketches, paintings, ink drawings, paper cutouts, block prints, comic strips, illustrated poems and art books that he produced as a child and adolescent.

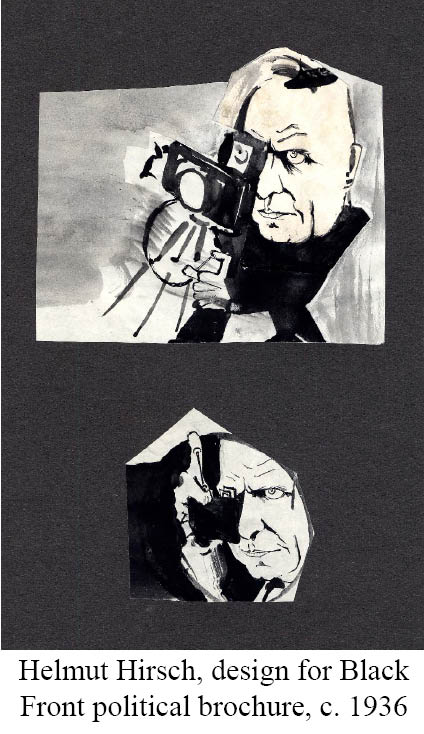

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 prevented Hirsch from attending university in Germany and he moved to Prague at the age of 19 to enroll as an architecture student at the Deutsche Technische Hochschule (German Institute of Technology). While in Prague, Hirsch became involved in the Black Front, a group of German expatriates and former Nazi party members who actively opposed Hitler. Hirsch was introduced to the group’s leader, Otto Strasser, by his mentor, Tusk (Eberhard Köbel), whom he knew from his former youth group, Deutsche Jungenschaft.

By the time Hirsch’s family joined him in Prague in 1936, he was actively involved in the underground activities of the Black Front, a secret he never shared with them. In December of 1936 Hirsch informed his parents that he would be going skiing with a friend; in fact, he was planning on returning to Germany to carry out the bombing of key Nazi targets. It appears that Hirsch may have wavered in his commitment to the plot, for rather than go directly to Nuremberg as planned, he took a detour to Stuttgart to meet a friend. What Hirsch did not know was that German agents had likely been infiltrating the Black Front for some time and the Gestapo was waiting to arrest him when he re-entered Germany. He was captured in Stuttgart.

By the time Hirsch’s family joined him in Prague in 1936, he was actively involved in the underground activities of the Black Front, a secret he never shared with them. In December of 1936 Hirsch informed his parents that he would be going skiing with a friend; in fact, he was planning on returning to Germany to carry out the bombing of key Nazi targets. It appears that Hirsch may have wavered in his commitment to the plot, for rather than go directly to Nuremberg as planned, he took a detour to Stuttgart to meet a friend. What Hirsch did not know was that German agents had likely been infiltrating the Black Front for some time and the Gestapo was waiting to arrest him when he re-entered Germany. He was captured in Stuttgart.

Hirsch was tried in secret before the so-called Volksgericht (People’s Court) in Berlin in March of 1937; he was sentenced to death for “preparation of high treason and criminal use of explosives endangering the public”[1]—despite the fact he was not carrying any explosives when the Gestapo apprehended him. By the time he was sentenced, Hirsch had been missing for three months and his family had no idea what had happened to him. It was only when his family heard his death sentence announced on the radio (March 20, 1937) that they learned of his fate. They immediately began to make appeals for his release and even sought the help of relatives in the United States.

Compounding the tragedy was the fact that Helmut Hirsch was technically an American citizen, because his father—who had lived in the United States as a young man—had been a naturalized American citizen. However, due to a bureaucratic error, Siegfried Hirsch’s American citizenship was revoked some time after he returned to Europe. By the time Helmut was born, he and his family were considered to be “stateless persons.” It was only when Hirsch was imprisoned that his family fought to reinstate his father’s as well as his own American citizenship, which was formally granted in April of 1937. However, neither this action, nor the diplomatic efforts of U.S. Ambassador William E. Dodd, was able to secure Hirsch’s freedom. The day before his execution, Hirsch wrote this final letter to his family from his jail cell [translated from the German]:

Compounding the tragedy was the fact that Helmut Hirsch was technically an American citizen, because his father—who had lived in the United States as a young man—had been a naturalized American citizen. However, due to a bureaucratic error, Siegfried Hirsch’s American citizenship was revoked some time after he returned to Europe. By the time Helmut was born, he and his family were considered to be “stateless persons.” It was only when Hirsch was imprisoned that his family fought to reinstate his father’s as well as his own American citizenship, which was formally granted in April of 1937. However, neither this action, nor the diplomatic efforts of U.S. Ambassador William E. Dodd, was able to secure Hirsch’s freedom. The day before his execution, Hirsch wrote this final letter to his family from his jail cell [translated from the German]:

June 3, 1937

Berlin-Ploetzensee

Dear Mother, dear Father,

I have just been told that my appeal for clemency was turned down. I must die then.

We need not say anything any more to each other. You know that in these last months I have really found the way to myself and to life. Real beauty must stand before unswerving honesty. You know that I have lived every moment fervently and that I have remained true to myself until the end. You must live on. There can be no giving up for you. No becoming soft or sentimental. In these days I have learned to say “yes” to life. Not only to endure it but to love life as it is. It is our own inner gravity, the force by which we have entered life.

It must help you in some way that I know I have finally reached my own inner image and feel complete. And in this feeling is much of our time and our world.

The only way I know how to thank you is by showing you until the last moment that I have used all your love and goodness towards becoming a whole being of my time and my heritage. Do not think of the unused possibilities, but take my life as a whole. A great search, a foolish error, but on its path to finding of final truth, final peace.

Please care for Vally[2] as for a child. I embrace you, dear mother and you, my father, once more for a long, long time. Only now have I realized how much I love you.

Yours forever,

Helmut.[3]

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department is most grateful to Katie Hirsch for donating her brother’s important papers to Brandeis University, and for translating a portion of the materials into English.

The Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department is most grateful to Katie Hirsch for donating her brother’s important papers to Brandeis University, and for translating a portion of the materials into English.

Notes

[1] “Secret Document in the Name of the German People” [photocopy], undated. From the Helmut Hirsch

Collection, Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department, Brandeis University.

[2] Helmut Hirsch’s girlfriend, Valerie Petrova.

[3] From the Helmut Hirsch Collection, Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department, Brandeis University.