T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land

July 7, 2014

Description by Max Goldberg, Archives and Special Collections Reference Assistant.

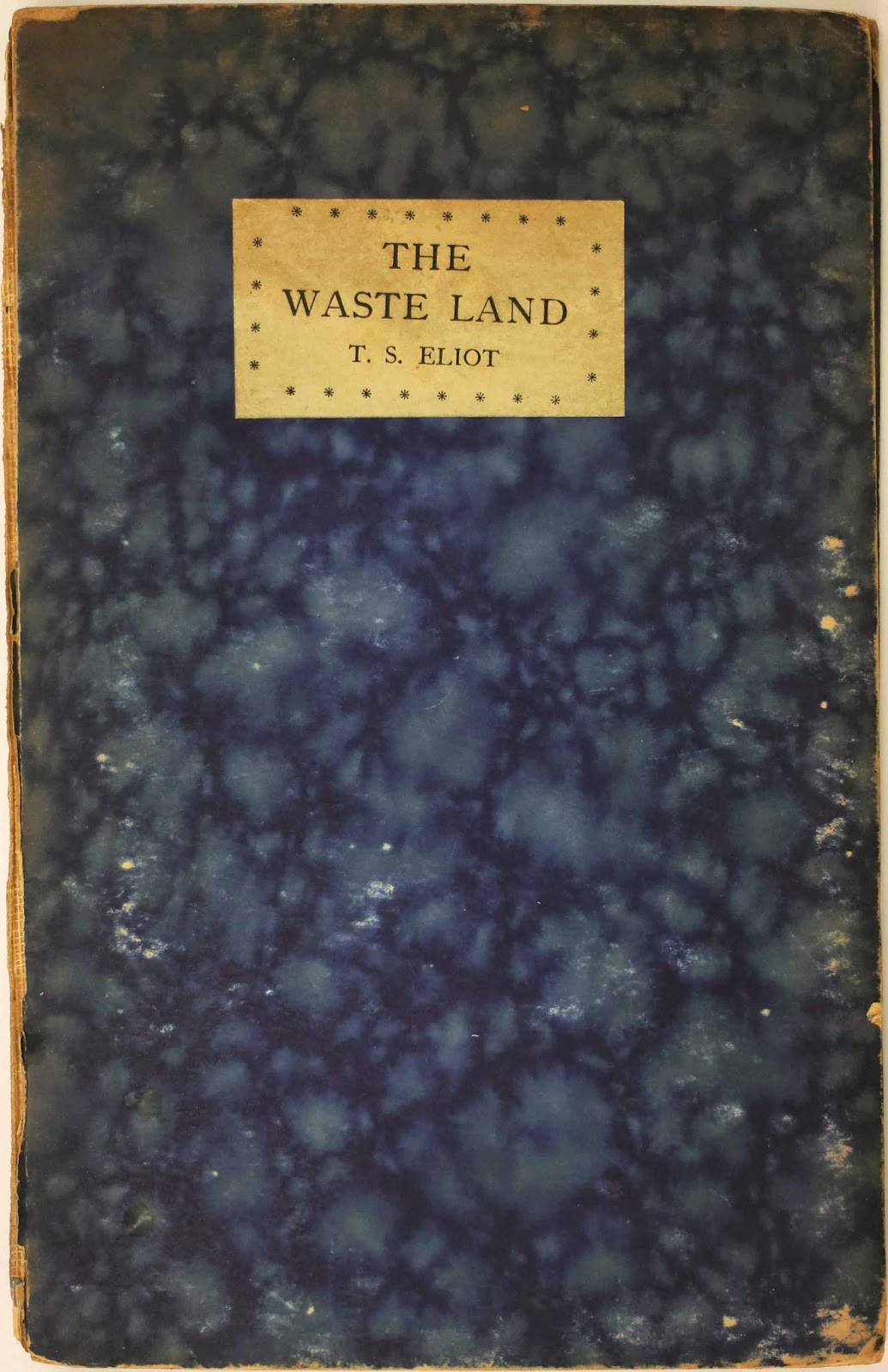

One could hardly hope for a more exquisite emblem of modernist print culture than the Hogarth Press 1923 edition of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” recently acquired by Brandeis University Special Collections. Printed in a run of 460 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s private press, with type set by Virginia herself, the Hogarth “The Waste Land” offers tangible evidence of the interconnectedness of English modernism.

One could hardly hope for a more exquisite emblem of modernist print culture than the Hogarth Press 1923 edition of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” recently acquired by Brandeis University Special Collections. Printed in a run of 460 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s private press, with type set by Virginia herself, the Hogarth “The Waste Land” offers tangible evidence of the interconnectedness of English modernism.

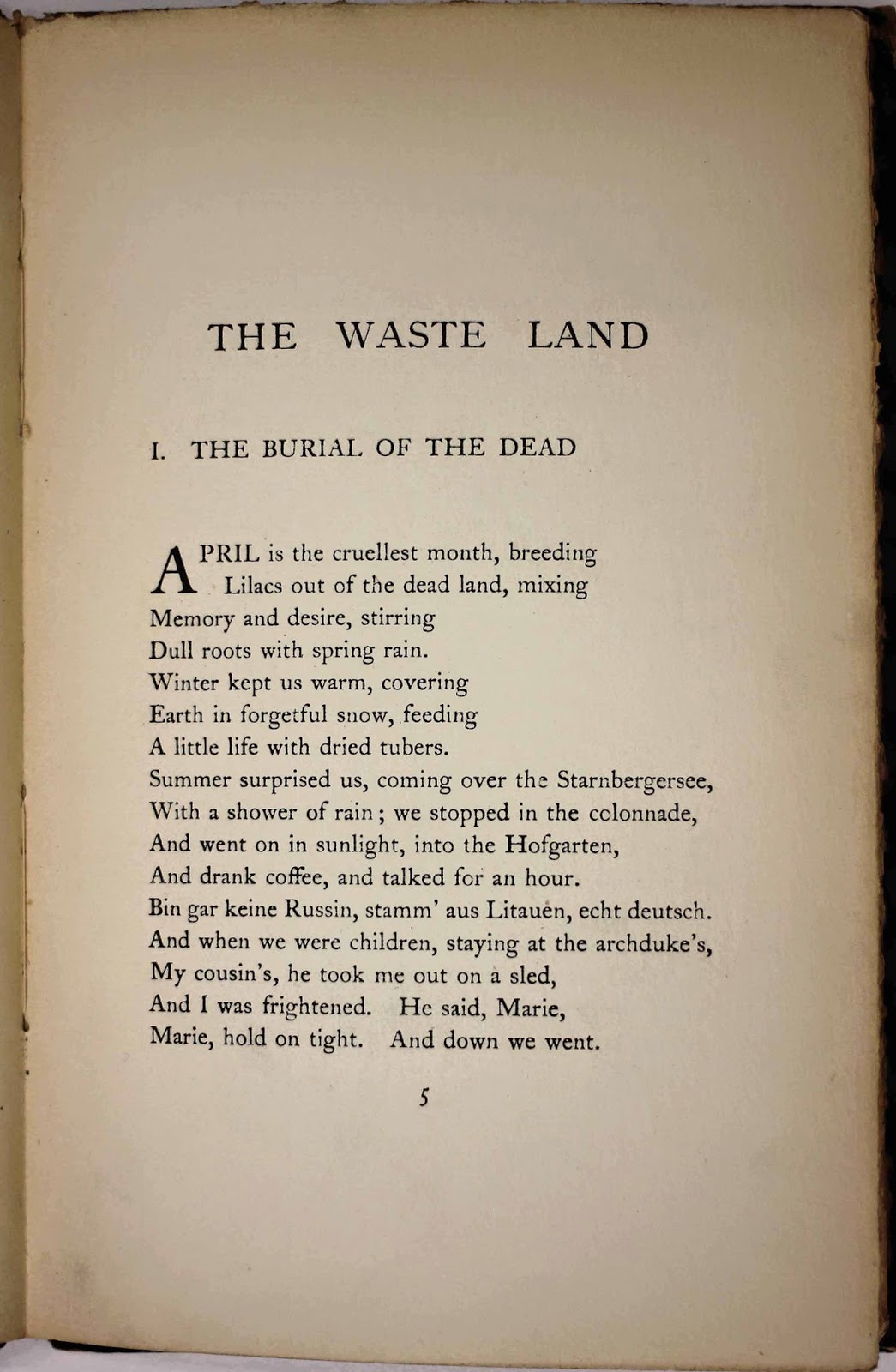

The Woolfs first met the expatriated Eliot through publishing his “Poems” of 1919. Friendship followed, and Eliot promised Hogarth the British publishing rights to his epic in 434 lines. Typically interpreted as an elegy for civilization, “The Waste Land” draws together multiple modes and voices, as well as an erudite command of the poetic tradition, in sounding its themes of loss and decay (“These fragments I have shored against my ruins”). As much a feat of scholarship as poetic imagination, “The Waste Land” is a poem that demands elucidation. Virginia Woolf’s own first impression of the poem, recorded in her diary, was characteristic in its mix of admiration and confusion:

“Eliot dined last Sunday & read his poem. He sang it & chanted it rhythmed it. It has great beauty & force of phrase: symmetry; & tensity. What connects it together, I’m not so sure. But he read till he had to rush… & discussion thus was curtailed. One was left, however, with some strong emotion. The Waste Land, it is called; & Mary Hutch [Hutchinson], who has heard it more quietly, interprets it to be Tom’s autobiography — a melancholy one”[1].

Indeed, Eliot himself would later plead that the poem represented “the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life… just a piece of rhythmical grumbling”[2]. And yet what grumbling! Autobiographical elements notwithstanding, the verses quickly came to be seen as a quintessential expression of modern disillusionment. For all the pessimism between its covers, though, the Hogarth “The Waste Land” is an uncommonly beautiful volume, emblematic of the Woolfs’ idea of literature as a labor of love. Holding the book one is struck above all by its delicacy, the blue marble cover drawing the eye into its recesses (one thinks of William Gass: “Blue is [the] most suitable as the color of interior life”). It reminds us that before “The Waste Land” was crowned by Harold Bloom as “indisputably the most influential poem written in English in [the twentieth] century,” it was a thing to be passed between friends.

Indeed, Eliot himself would later plead that the poem represented “the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life… just a piece of rhythmical grumbling”[2]. And yet what grumbling! Autobiographical elements notwithstanding, the verses quickly came to be seen as a quintessential expression of modern disillusionment. For all the pessimism between its covers, though, the Hogarth “The Waste Land” is an uncommonly beautiful volume, emblematic of the Woolfs’ idea of literature as a labor of love. Holding the book one is struck above all by its delicacy, the blue marble cover drawing the eye into its recesses (one thinks of William Gass: “Blue is [the] most suitable as the color of interior life”). It reminds us that before “The Waste Land” was crowned by Harold Bloom as “indisputably the most influential poem written in English in [the twentieth] century,” it was a thing to be passed between friends.

The Hogarth edition was actually the fourth printing of Eliot’s poem, following appearances in British and American magazines (“The Criterion” and “The Dial,” respectively) as well as a book edition brought out by the American house Boni and Liveright. Eliot was reportedly happiest with the Hogarth edition, which surely owed to Virginia Woolf’s care in preparing the pages. Historians note with characteristic understatement that “The Waste Land” is “typographically challenging.” Woolf put it more vividly in her letter to Barbara Bagenal of July 8, 1923: “I have just finished setting up the whole of Mr Eliots [sic] poem with my own hands: You see how my hand trembles.” The Woolfs were typically more staid in their poetry selections, and it’s tempting to imagine that Virginia’s experience typesetting “The Waste Land” by hand might have influenced her own increasingly experimental approach to language. Reading her later novels, one often has the sense that each discrete word and phrase has been carefully selected not only for its meaning but also for its sound and even its appearance on the page: a degree of attentiveness that is usually the province of poets.

The Woolfs would not be the last publishers to lavish special attention on Eliot’s epochal poem: in 2011, Eliot’s own publishing house, Faber & Faber, released an enriched version for the iPad. With its dazzling web of reference and allusion, “The Waste Land” would seem a natural subject for the electronic environment. It proved a hit in spite of Wired’s amusing complaint that the program “eats up a staggering 951 MB of memory”[3]. One imagines Eliot being disappointed that his erudition didn’t total a gigabyte and Virginia Woolf similarly disconcerted by the name of the app’s production company: Touch Press.

For More Information

See Cassandra N. Berman’s earlier Women in Publishing post for more on the Hogarth Press.

Notes

- Quoted in Willis Jr., J.H. Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers: the Hogarth Press, 1917-1941. (Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 1992), 72.

- Quoted in Pericles Lewis’ article on “The Waste Land”

- Wired review of The Waste Land app