New Documentary Film about Tibetan Dance

By Tenzin Dasel, Brandeis University ’22, and Toni Shapiro-Phim, Program in Peacebuilding and the Arts

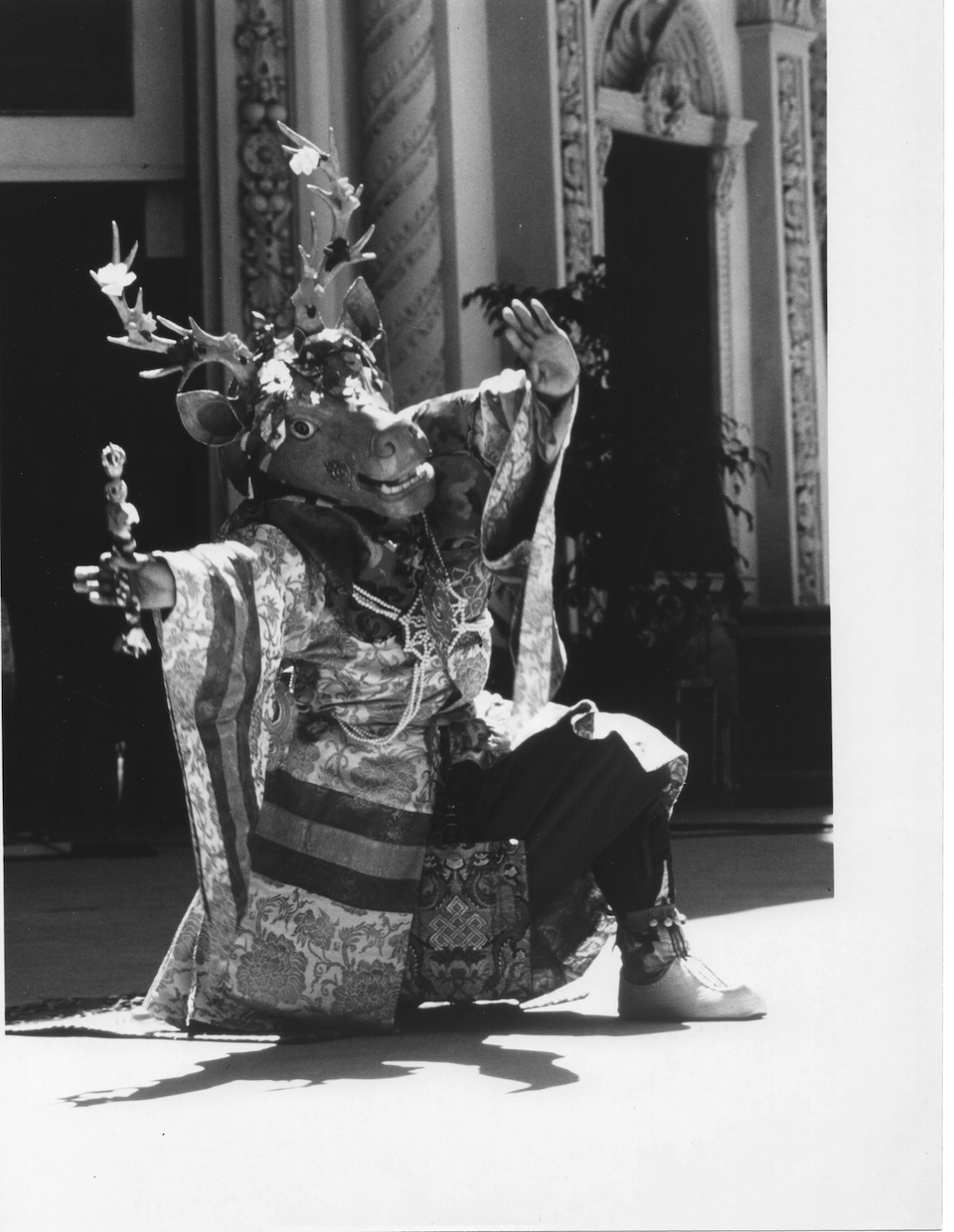

Tibetan ritual dancer Losang Samten – who is also an award-winning visual artist and the spiritual director of the Chenrezig Tibetan Buddhist Center of Philadelphia (USA) – recently worked with filmmaker Aidan Un to craft a documentary film about Tibetan ritual dances and the context of their performance. In particular, the focus was on a series of ritual dances historically performed at Namgyal Monastery, the monastery of the Dalai Lama. Using archival footage and contemporary interviews, they pieced together stories of dances that, among other things, contribute to the elimination of attachment, pride, and ignorance by guiding the metamorphosis of these negative attributes into equanimity and wisdom. Every element of the dances – the elaborate costumes, gestural language, masks and headdresses, musical accompaniment – is infused with layers of symbolism.

The need for this kind of documentation is acute, according to Losang Samten. He fears that knowledge about the dances is being lost as generations in the diaspora are removed from their homeland, and as suppression of Tibetan cultural practices continues in Tibet. “The older generation is already passing on, and I had the chance to study the ritual dances from great masters. So, I thought oh, now if I die due to Covid-19 or whatever, you know, this will truly be lost. Which is why I decided to do this documentary.” In addition, “each monastery has a totally different way of performing the ritual dance… [The monks of] Namgyal Monastery have a very unique ritual dance. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s monastery’s ritual dance has been known to be in existence since the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama… There are a lot of ritual dances that look the same – costumes look the same – but how to dance, and how to dance along with the music and chanting, are very different.”

The Chinese government invaded and then consolidated control of Tibet in the 1950s. Since the brutal quashing of the 1959 national uprising against Chinese domination, and the flight, that same year, of the Dalai Lama (Tibet’s spiritual and, at that time, political leader as well) to safety in India, Tibetans in their homeland have experienced enormous oppression. Thousands of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries have been destroyed; Tibetan language use and spiritual practices have been regulated and restricted, including the teaching and performance of ritual dances.

More than 125,000 Tibetans live in diaspora, mainly in India, but also in Nepal and Bhutan, as well as in Australia, Europe, and North America. The Tibetan Government-in-Exile is in Dharamsala, India, the home of the Dalai Lama. Tibetan monks at the Dalai Lama’s monastery, and at Tibetan Buddhist monasteries throughout India, continue to pass on elements of treasured cultural knowledge through the creation of sand mandalas, thangka paintings, and other ceremonial objects, and through the performance of dances as part of specific ceremonies. “Until 1959, every year in our capital of Lhasa, these ritual dances were performed at Potala Palace,” says Losang Samten. “This is one of the big winter occasions… His Holiness the Dalai Lama and his teacher, his family, all our government officials, and so many people would participate in the ritual dance.” Soon after the Dalai Lama established a new home in India, Losang Samten adds, there was little money for all the elaborate costumes and accoutrements; nowadays, there is funding, but so many of those with the cultural knowledge in their bodies are no longer with us. Out of all “the monks who came to Namgyal Monastery in 1959, only one is left.”

It is Losang Samten’s hope that this documentary film, entitled Tse Gutor [a series of dances that make up a particular ritual of the Dalai Lama’s monastery], narrated in Tibetan with English subtitles, will be a record of a uniquely consequential Tibetan cultural practice. “Almost no monks in the diaspora can do this dance! So, if I don't put this together, no one can. This isn’t because I am special or anything, but because I am in a position to put my knowledge, and that of surviving others, together.”

Losang Samten continues: “Tsawa ne lakpa: Tsawa means root. So tsawa ne lakpa means it is completely lost from the roots. This is what Tibetans will become if this cultural loss, including the loss of these ritual dances, continues… At the end of the documentary, I said “Save Tibet.” That's the message. I have written in big letters SAVE TIBET in Tibetan as well as English… We are trying to preserve our culture, but, if we don't have a Tibet, eventually it is all going to be lost.” For information about screening the movie, please contact Losang Samten.