Marcia Freedman Papers

Joyce Antler on Marcia Freedman

From "Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women's Liberation Movement"

New York: New York University Press, 2018

Marcia Prince Freedman was the daughter of a New Jersey homemaker and labor-organizer father, a Communist Party member who raised her to pay attention to social class and power relationships, lessons that she was later able to translate into a gender analysis. Unusually for a Communist, her father was also an energetic Zionist, proud that his daughter won an American Jewish Congress essay contest that sent her to Israel in 1956 while still in high school, but he opposed her taking up residence there when she fell in love with the country.

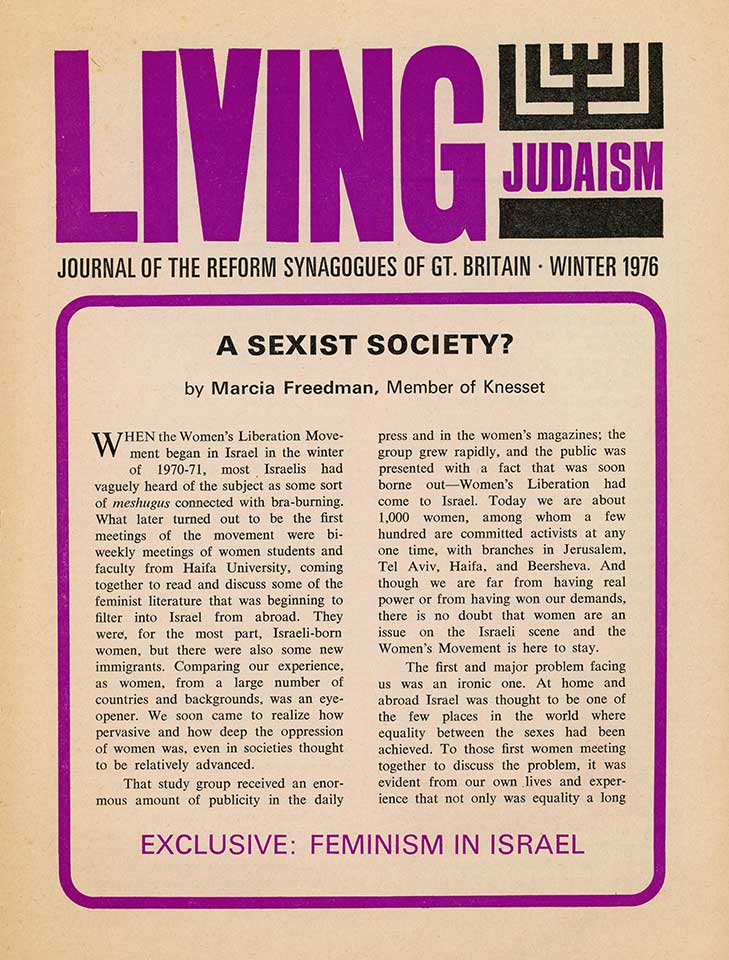

Winter 1976 Living Judaism journal with "A Sexist Society?" by Marcia Freedman

Winter 1976 Living Judaism journal with "A Sexist Society?" by Marcia Freedman

After graduating from Bennington College in 1960, Freedman married and had a child. She earned a Masters degree in philosophy, putting her Ph.D. on hold; instead she typed her husband’s dissertation (“five times”). She accompanied him to Israel in 1967, shortly after the Arab-Israeli War, when her husband received a fellowship from the University of Haifa. She began to read “Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan, Shulamit Firestone, Ellen Willis, Charlotte Bunch, Kate Millett.” Her consciousness raised, she started Israel’s first women’s liberation group after teaching a course at on the subject at Haifa University.

Though ultimately disillusioned with Israeli politics, initially Freedman was exhilarated by the country’s attempts to become a “full-fledged social democracy.” Being part of the dominant group was another attraction. In the U.S., she says, “I had such a minority mentality.” With a “well developed political head” inherited from her father, Freedman grew up alienated from non-Jews, “rich people” — “whoever it was.” The Holocaust loomed large, and in her teenage years, she just “read and read and read and read” about it. Her consciousness of anti-Semitism was strong. If she were in a group of people who didn’t know her, she would “say something that would indicate to them that I was Jewish so that they wouldn’t embarrass themselves by being anti-Semitic.” This consciousness gave her “a certain historical understanding of persecution and therefore of oppression and suppression and domination.” She believes that the awareness of anti-Semitism was “built into our identity as Jews. … The more [identity] we have [as Jews] the more easily that slides into other kinds of activism.”

In Israel, though, “all of this Jewish self-consciousness just fell away.” In a sea of Jews, she no longer felt peculiar. “I stopped being the Jew…” Freedman’s feminist identity now occupied the foreground, and she became an outspoken feminist pioneer in her adopted country. As part of the dominant culture, it was easy for her see the “contradictions between a feminist and being identified as a Jew.” Unlike in the U.S., where many issues raised by radical feminists had already entered the mainstream, in Israel the problems that Freedman raised, especially those connected to a woman’s body — “rape, beatings, incest, teenage prostitution, breast cancer prevention, fertility management, abortions” — were “enveloped in a conspiracy of silence.” She realized that the “first victims of Israeli statehood were Jewish women.” Support offered by American Jewish feminists Letty Pogrebin, Esther Broner, and Phyllis Chesler, who made frequent visits to Israel, proved crucial.

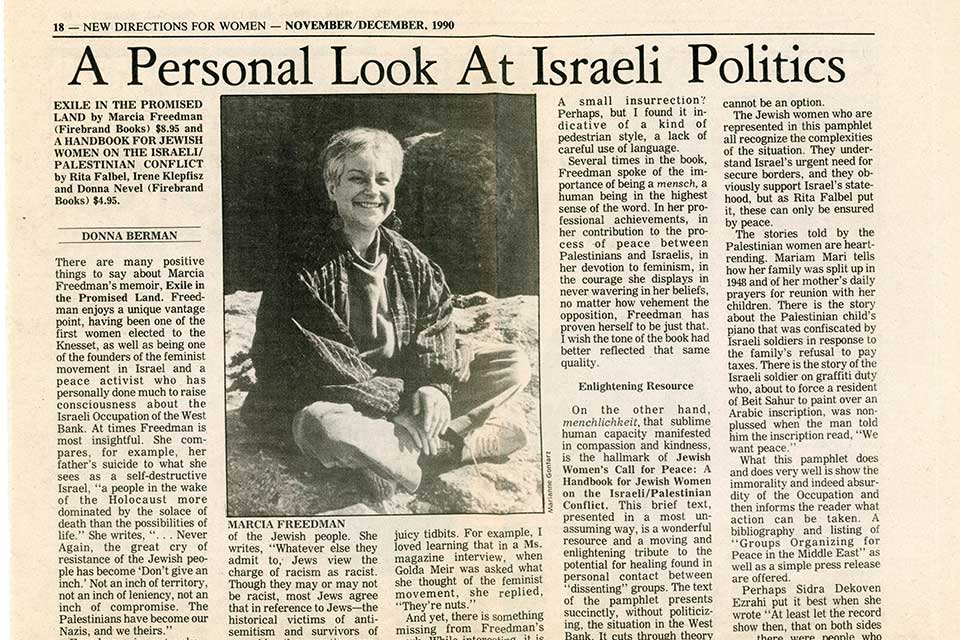

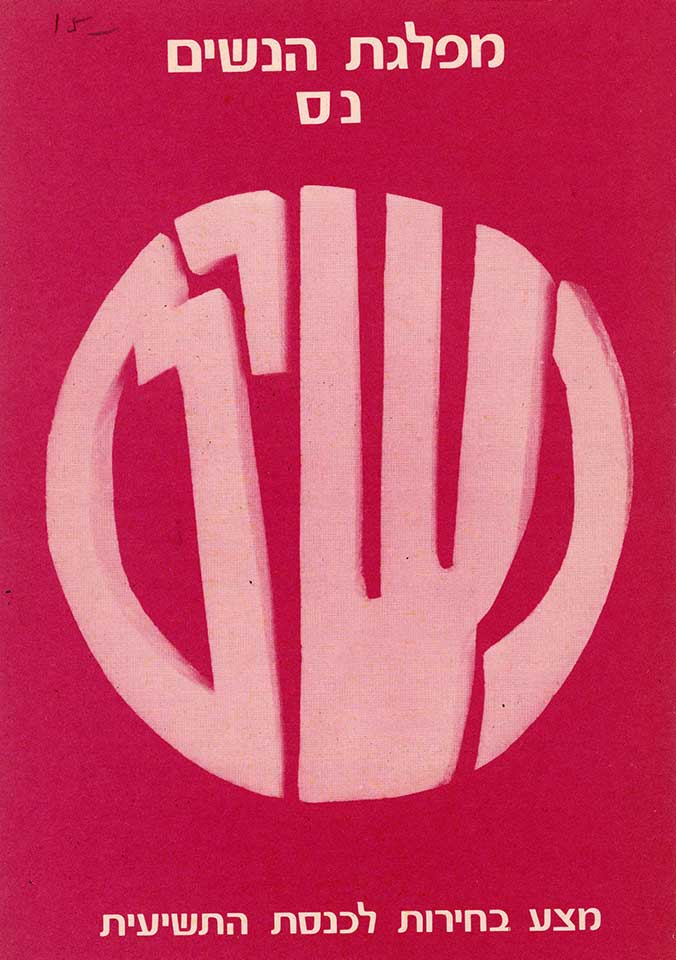

Freedman’s marriage ended, and she became known for her feminist work. To much of Israeli society, however, feminism seemed to be an extremist movement and an “American import.” In the Knesset, to which Freedman was elected on the line of the civil rights party, she was considered a “radical extremist” for her “unseemly subject matter” — women’s and peace issues. When she left the Knesset, she came out as a lesbian.

After her return to the U.S. in 1981, Freedman relearned “what it is to be in the minority, to be self-conscious, vulnerable and somewhat frightened and to relearn about anti-Semitism.” She resided in Berkeley, California, where she worked with Israeli/Palestinian and American women’s peace groups. “As feminists we have an obligation to appreciate the history of the Palestinians and the legitimacy of their drive towards self-determination,” she wrote in 1985. “We have the same right to expect their appreciation of our history as Jews.” In 2002, she became founding president of Brit Tzedek v’shalom, the Jewish peace group that lobbied for a two-state solution. She continued to spend extended periods of time in Israel fighting for women’s rights. But alienated from mainstream politics in both countries, Freedman never felt completely at home there or in the Diaspora

“Most of us, as feminists, find ourselves in an adversary position vis-à-vis our governments, our economies, and our cultures,” Freedman maintained. “We may want to love them, but experience and accumulated wisdom teaches us that we cannot. This is no less true for Jewish feminists vis-à-vis Israel than it is for American feminists vis-à-vis the United States.” Her identity as a Jewish feminist provided her with the greatest sense of community and belonging.