Waters Breathe, Too: An Anthology

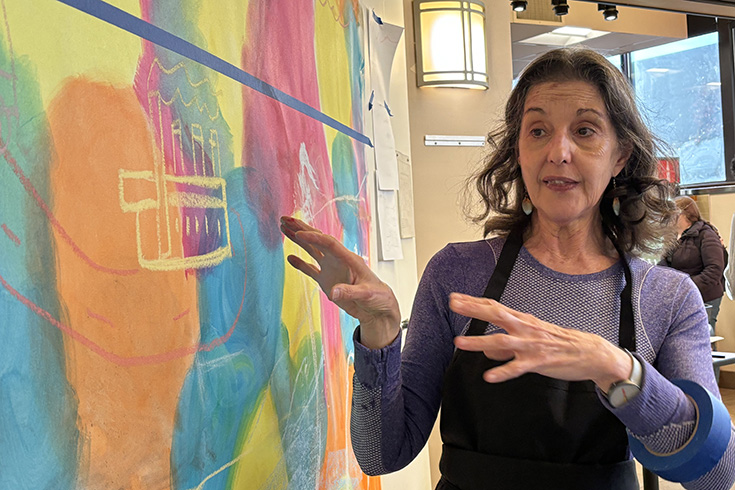

Photo Credit: Toni Shapiro-Phim

Below are notes about interviewees' stories that inspired the creation of images that appear in the mural.

The person that I interviewed has spent time living in Rochester, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Miami, Florida; and Shanghai, China, before moving to Waltham, Massachusetts, holding citizenship in multiple countries. She shared two very moving stories with me during our time together. The first story she shared was regarding the Yellow River in China, one that runs through a city and is filled with pollution. She explained how she walked by it every day in high school, and wondered what the walk would be like if the pollution was not as prominent. She was saddened by the pictures and videos she saw online of clear blue waters, and wished that it was something she could experience. The second story that she shared with me was about hurricanes in Miami. She detailed the mass destruction that they caused, and the panic that they caused within the community. My subject told a beautiful story of Asian Catholic churches with large stained glass windows opening their doors to those in need, providing food, shelter, warmth, and music. In a primarily white and Hispanic area, these churches provided her with a sense of cultural community. She explained that while water is often a beautiful natural resource, it can be very scary and destructive. She has mixed emotions surrounding it, as she has grown up in an environment where it was both something to fear and something that needed improvement.

--Anna Martin--

My interviewee grew up in Glasgow, Scotland—a former industrial powerhouse once renowned as the Second City of the British Empire. He shared stories of family members who worked in shipbuilding in the Firth of Clyde, an inlet close to Glasgow and a hotspot of economic productivity for all of Great Britain in the first half of the 20th century. He pointed out that even one of the country’s most beloved comedians, Billy Connelly, spent some time working in Glasgow’s shipyards—the industry generated not just jobs and wealth but also collective points of cultural memory. He also shared stories of biking out to the Firth of Clyde with his father as a young boy, further demonstrating this body of water’s special place in the hearts of Glaswegians. For my interviewee, the Firth of Clyde symbolizes Glasgow’s historical prosperity—and, by contrast, the city’s decades of economic stagnation (with some exceptions) starting soon after the end of World War II. He hopes for a future in which water is treated, in the UK and beyond, as the necessity for survival, natural treasure, cultural touchstone, and economic boon that it truly is. This hope is represented by the docked ship in the mural’s bottom left.

--Bella Cameron--

In my interview with a woman from Liberia, her vivid recollection of her early years stood out profoundly. Born in Liberia, her first encounter with the ocean was a momentous occasion that left an indelible mark on her life's story. Her connection with water went beyond mere entertainment or sustenance; it symbolized a profound tie to her childhood spent playing in the river near her home. This relationship with water transcended generations, encompassing an annual tradition of replenishing the river with essential resources—a practice emphasizing the interplay between culture, environment, and tradition. As she recounted, an older woman played a pivotal role in her life's journey, highlighting the importance of having mentors. At the same time, her engagement with water speaks volumes about preserving memories and sustaining the environment. Her oral history vividly illustrates the multilayered significance of personal narratives, cultural heritage, and the intricate relationship people have with their surroundings.

-- Audacy Sheffield--

My interviewee is from Jamaica, and currently lives in the US. The story I’d like to share is the one that inspired my main contribution to the mural, which is the story of how she learned how to swim. She told me about how every so often her and her family would load up the car and take trips to the beach. Her uncle was known for throwing the younger ones into the water in an attempt to teach them how to swim. So, on this particular day, she decided that she had had enough of that, and that she was going to teach herself how to swim. It was difficult at first, but eventually she got the hang of it, and the process was very healing and freeing for her, as she was able to take her safety into her own hands.

--Caden Daubon--

The part of the mural that has resonated the most with me is the small section portraying filthy,

polluted water, which was a result of the factory, also depicted in the mural. As someone from

New York City, I have always felt a deep connection with water but found it hard to fully

appreciate the bodies of water I had access to because there was always trash or some kind of

pollution obstructing its natural beauty. My interviewee, who is from Uzbekistan, shared a

similar story. She enjoyed playing in a body of water close to her house, with her family

members and friends. However, the government began to shut off their water access out of greed,

making it harder for her to enjoy the water with her community. I believe that the mural reflects

how human intervention can destroy the natural beauty of water, and can even go as far as to

corrupt the peace and serenity of nature, ruining it for all of its inhabitants, including ourselves.

My main contribution to the mural was the group of protestors next to the factory. My vision was

to convey to viewers that change doesn't just happen but rather is an arduous process that

requires sacrifices from each and every one of us, and if we want to make a difference we must

embrace this process. A key part of that process is standing up against corporations who have the

most significant impact on the environment, whether that means boycotting their products,

rallying awareness, or, as depicted in the mural, acts of public protest. To me, the message of this

mural is that we must try our hardest to preserve the bodies of water we hold dear, and make sure

that we do not interact with them in a way that can cause irreparable harm.

-- Elijah Rabin--

The person I interviewed is from Gujrat, India, and moved to the United States when they were 11. Despite having not been to India in over 10 years their impressions and opinions surrounding the water they grew up around were very image-invoking. In their interviews they recounted stories surrounding several different bodies of water in India, the first being a lake near the village they grew up in. This lake was right next to a temple of the Hindu goddess said to protect the village from the lake. The interviewee described the lake as very dark and murky and voiced their concerns about the possible pollution of the lake. While the interviewee’s concerns about the water were worrying, what I found most interesting was the relationship between the lake and the goddess who protected children from the lake. The interviewee’s focus on the religious connection to the lake helped me to understand how they viewed water. This religious connection to water was especially relevant as the interviewee spoke about the second body of water, the Ganga River. The Ganga River is said to be one of the most important places in Hinduism, as the river is a gift from the god Shiva. Through listening to the interviewee speak about these two bodies of water I gleaned that the person I interviewed held a reverence for water supported by their religious affiliation. When I showed the interviewee the mural after it was completed, they said that the polluted part of the water really reflects how they saw the lake in the village they grew up in.

-- Eliza Bier--

In my interview with Dr. Alex, the critical issue of water scarcity was highlighted. The distribution of water resources worldwide is grossly unequal. While some individuals use water for activities like gardening, others are compelled to drink water even dirtier than that used for gardening solely for survival, with children falling ill after drinking contaminated water. Additionally, the freshwater sources used in our daily lives are not an infinite resource; they are steadily dwindling, and water is one of the most scarce resources in the world that nourishes all life on earth. Unfortunately, the technology to convert seawater into freshwater remains impractical on a large scale due to cost constraints. Moreover, if people resort to excessive groundwater extraction due to water scarcity, it could potentially contaminate entire groundwater systems. I chose to reflect on the mural's depiction of lush greenery juxtaposed against barren landscapes, mirroring Dr. Alex's discussion. On one side, vibrant green grass thrives abundantly, while on the other, there's desolation and lifelessness. This stark contrast serves as a stark reminder that the journey to safeguarding water resources is an immense and ongoing challenge. It highlights the disparities in water availability and underscores the urgency to address this global issue, ensuring equitable access to clean water for all.

--Gloria Feng--

Water is the past, water is the present, water is the future, water is everything all at once. You cannot distinguish from the very different stages that it assumes, as it blends them into a single entity. That’s what I see in our mural, a blending of different things, different stories, coming together as a unity to tell a bigger story of continuity, flow, and growth. And this is exactly what my interviewee said to me: be water, my friend (borrowing the phrase from Bruce Lee, who was in turn influenced by Taoism). Molding ourselves to fit the situation we are experiencing right now is the embodiment of the idea of water as a shapeless, yet completely moldable structure. Because of this property, water can represent various states, from the memories of the past, going through the hardships of the present, to the hope for the future. Our mural represents this amalgamation of stories that end up touching on the moments of the chronology of almost all societies, with emphasis on the future that we envision to create. And just by showing the circle of water, our mural can be a representation of the circle of life itself.

--Gustavo Nascimento--

My interviewee is from Chengdu, China. She has expertise in Environmental Science. She introduced the Tuojiang River to me: it is the “mother river” of her hometown. When she was young, she usually played around in the park near the Tuojiang River, but it was gradually polluted as she grew up, which gave her the thought of protecting the river. The emotional connection between the Tuojiang River and her pushed her to major in Environmental Science. She explained two main types of water pollution: point source pollution, which indicates any one specific, identifiable source of pollution, like a ship, factory smokestack, ditch, or pipe, from which pollutants are released; and non-point source pollution, which is diffuse contamination of water or air that does not originate from a single discrete source. In the mural painting, the mining factory is an example of point source pollution: it causes lots of polluting materials and dumps them into the river; the acid rain is a symbol of non-point source pollution, because it is not the product of a single, distinct source. Through our mural, we can educate people on our campus about these two kinds of pollution.

--Helen Ma--

My interviewee is from Rhode island and is a professional scuba diver who makes his

living by catching the crayfish undersea. One of the perspectives that he shared that resonated with me the most is that he said: I could see some of the most beautiful aspects of this area of water as a professional diver because I’m here all year round. As recreational divers or just visitors around the waters, people might only go around that water area when it’s a holiday season. However, he appreciates the view of the water most from his little boat during autumn, which is the time people don’t really visit there. The special perspective from a diver was the key during our conversation. In the mural, coincidently, there is a metaphor that is present that might have

some similarity with the “special perspective” of the diver. In the “past” section, the diver who jumps from the boat is the only person who is on the river, and all the other characters are either by the sea or on land. I think this little guy who was the only one on the river might have a very different view of those rough blue waves that rolled his ship along than others do.

--Jennifer Zhang--

For our mural project I interviewed a woman from Cyprus. She told me about the river that ran along the village she lived in as a child. Cyprus has an immense lack of water, especially in the summer when it is extremely hot. When late winter and early spring would come back around, the river would be filled with an abundance of life, and she would bring her friends and siblings there to play and catch frogs.

Unfortunately, over time, the river has been corrupted by tourism. Tourism has not only impacted this river alone, but all of the water on the island of Cyprus. In our mural, I painted a factory to represent the impacts that tourism and industrialization have on bodies of water. The run off from the factory is going straight into the river, causing a large amount of pollution. Tourism is a leading cause of water pollution in countries all over the world. Tourism degrades coastal areas by increasing the amount of plastic pollution on both the beaches and in the waters. Water is one the most important natural resources on earth, and it must be protected. Water is necessary for survival, and if we do not start protecting our waters, soon all living things will suffer the consequences.

--Julianna Lapham --

I interviewed a friend of mine from Berlin Germany; she is extremely passionate about combating the climate crisis, especially preserving all bodies of water. She told me a story about a time she went kayaking with her family in the Spree, a small river in Germany, which she said was so fun and relaxing, but she was also quite disturbed by how polluted the water was. She mentioned that she saw multiple dead fish and rats and some plastic in the river and joked with me that if she would have fallen into the water, she might have grown a third eye. And while she laughed at her joke, I could see in her eyes how upset she was with the massive pollution in one of her favorite rivers. She continued to tell me that despite the river’s pollution, being by it was very relaxing. She would hear the birds chirping and look at the nice vegetation surrounding her. The polluted water that is painted on the mural with great detail, showing the dead fish and plastic bottles, reflects my friend’s story really well.

--Maytal Storm--

My interviewee shared stories of tranquility and spirituality. From Quito, Ecuador, he told me about the paramo of the Andes, recalling the beautiful and diverse wildlife that inhabits this area, but also one particular waterfall that he lacked much vocabulary for except to call it incomparably peaceful. He described the water as being crystal clear, the surrounding fauna as complex, and the landscape as serene. In our interview I learned of the folklore that describes this land as being full of fairies and elves, highlighting how wonderous the area truly is. He told me stories of sharing the land and waterfall with friends and family, and the joy it has always brought him; this place is a spiritual experience. My interviewee expressed concern that mining in the Andes would soon lead to severe contamination of water sources just like his favorite waterfall. He also expressed concern that Indigenous communities would be first and most affected by this mining. With a new Ecuadorian president, he was hopeful that environmental issues would gain some traction and his concerns might be addressed. Furthermore, he recently graduated with a degree in environmental studies and has dreams of making significant impact in the field. Despite his worries, there is hope, and I found that to be incredibly powerful.

--Samaria Dellorso--

The woman portrayed in the mural, standing on the cliff and reaching out to the ocean below, is my interviewee, hailing from Japan and presently residing in the Bay Area. She shared that the cliff holds a special significance for her as a hidden retreat, where she can unwind and feel a deep connection with the water, alongside her dog. She even expressed a desire for her ashes to be scattered off the cliff after her passing. In the mural, her open arms convey a posture embodying acceptance and a genuine appreciation for the present moment and the world. Beyond this, her stance serves as a symbolic embrace of the current state, positioned at the mural's center. It signifies the collective dedication to protest against factories and any detrimental actions leading to water contamination. Additionally, this embracing posture holds a deeper meaning, encapsulating the memory of a bygone era when clean water bestowed its benefits, fostering happiness and mindfulness among everyone.

--Shawn Koo--

My interviewee is from Israel. There were three bodies of water that were important to them growing up - the Mediterranean Sea, the Dead Sea, and the Kinneret (Sea of Galilee). The Kinneret was their favorite for a few reasons. They loved the contrast between the smooth lake in the foreground and the tall mountains in the background. The water itself was calm, fresh, and sweet compared to the salty, wave-filled seas that they frequented close to their house. The lake being somewhat far from their home gave them a chance to enjoy a ride on their motorcycle every time they visited. My interviewee holds very fond memories of spending time at the Kinneret with family, friends, pets, and later on their own children. One of their favorite memories is about the first time they brought their dog to the lake. They took him into the water on a swim board, and when they reached the middle of the lake the dog decided he wanted to return to the shore and jumped off. It didn’t take long for the dog to get tired of swimming and he came to my interviewee for help. But he was flapping his paws so wildly that they had to hold him like a lifeguard saving a someone drowning, making this quite the amusing spectacle for any onlookers.

The Kinneret is one of the most important sources of freshwater in Israel, and there are concerns about its survival due to human destruction and the climate crisis. People who visit the Kinneret don’t always treat it respectfully, which ends up harming the water. There have also been some years where the water level in the lake has plummeted and it wasn’t safe to utilize due to contamination by groundwater. If longer and tougher drought seasons continue then this contamination can reach a point of irreversibility. The demise of the Kinneret will not only negatively impact those who rely on it, but it would be a great loss of natural beauty. My interviewee emphasized the hope they have for citizens and governments all over the world to band together and preserve bodies of water, like the Kinneret, as they help sustain the Earth and humanity.

This scene, specifically the characters I circled, remind me of my interviewee’s story. I interpret the little animal to be the dog, and the person diving into the river is my interviewee coming to ‘rescue’ their dog (as a lifeguard would).

-- Shir Talmor--

Drawing inspiration from the oral history of my interviewee, a Fijian who found her life intertwined with water, the mural's future section echoes her journey. My interviewee’s story unfolds in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, a pivotal moment when she was grappling with career decisions post-graduation. With a background in competitive swimming and varied experiences in translation and teaching English, she faced a life-altering decision: whether or not to move to Thailand for a potential swimming opportunity. This decision, made under uncertain and challenging global conditions, mirrored the uncertainty and flux symbolized by the water in both her life and the mural.

The mural's future section, portraying a girl standing on a cliff overlooking a rejuvenated, clean river, resonates deeply with my interviewee’s narrative. This figure, reminiscent of my interviewee, symbolizes hope, resilience, and the pursuit of dreams against all odds. It is a powerful representation of her journey, highlighting her dedication to swimming despite numerous challenges, including balancing academics, work, and her passion for swimming. Her story of relentless pursuit, guided by her faith and a sense of purpose, is captured in the mural's imagery of clean, flowing water, signifying a return to purity and potential.

Moreover, the figures swimming in the river in the mural embody my interviewee’s commitment and joy in swimming. They represent not only her personal journey but also the broader human connection to water as a source of life, challenge, and renewal. This section of the mural, with its optimistic vision of the future, encapsulates my interviewee’s aspirations, particularly her dream of participating in the Olympics. It reflects the transformative power of water in her life, as both a physical element and a metaphorical symbol of her journey towards achieving her goals amidst life's turbulences.

--Sophia Liu--

Hundreds of years ago, complex systems of tunnels were dug throughout Afghanistan to bring water from the mountains to people all over the landlocked country. These tunnels and the reservoirs they feed are known as the Karez, and to this day they provide water for drinking, bathing, and irrigation of crops all across Afghanistan. In my research for this mural project, I interviewed my friend from Afghanistan. My friend told me about nearly drowning in his village’s Karez when he was a young child. He had been sitting on the side, watching his brother and friends swim, but he didn’t know how to swim himself. When another child pushed him in, the water was deep enough to cover his head. He was pulled out of the water after several moments of panic. Despite this rather traumatic formative experience, my friend spoke to me about the Karez system with clear admiration. Along with its innovative original purpose as an irrigation system, I learned that the tunnels of the Karez also served as valuable routes for escape and weapon transportation during the Soviet-Afghan war in the 1980s. Unfortunately, the Karez system is now falling into disrepair. Climate change has caused the water supply in the mountains to dwindle, and as the tunnels have dried up some have begun to cave in. As the Karez has become less reliable, the wealthy have turned to solar-powered wells to pump their water up from deep underground. These wells are depleting the underground water sources faster than deeper wells can be built. My friend proposed a plan of investing in the repair of the Karez system so that the people can use both the Karez and the wells without relying solely on either one, making it easier to avoid overdrawing any one water source. The mural’s depiction of a hopeful future that will take work to achieve reflects the sentiment of this idea.

--Triona Suiter--