Teaching Portfolios

Whether you are a current or future faculty member, and whether you are actively on the job market, compiling a dossier for promotion or a teaching award, or just looking for an opportunity to step back and reflect on your identity and priorities as an instructor, this module will walk you step-by-step through some of the key considerations involved in telling a story about your teaching.

The Cover Letter

If you're on the job market, your dossier generally includes a cover letter that speaks to both your past experience and future potential in research, teaching, and professional service. The discussion of teaching:

-

generally follows your 2–3 paragraph discussion of present and future research, and ideally begins with a transitional sentence showing some connection between them.

-

typically reiterates a couple of the most important points from your teaching statement with regard to your priorities/commitments/distinctive approaches to teaching in general.

How Specific Should I Be in my Cover Letter?

In most fields, it is this portion of the cover letter—rather than your standalone teaching statement—where you are meant to mention specific courses you would hope to teach, with an eye to showing how you would meet the department’s unique curricular needs. That said, there are several fields (e.g. computer science, and other engineering fields) where we hear that it is customary for the teaching statement to also go into this level of particulars.

Some Helpful Resources Re: Cover Letters

-

UPenn's Career Services offers advice and a number of examples of Cover Letters for Faculty Job Applications

-

UNC's Writing Center has a helpful page on Academic Cover Letters

-

Leonard Cassuto's "6 Tips to Improve Your Cover Letter" from The Chronicle of Higher Education

Teaching Statements

The 1–2-page Teaching Statement (sometimes called a "Teaching Philosophy Statement") is arguably the most important item within a teaching portfolio. For one thing, it gives the reader the most comprehensive, unified, narrative sense of your identity, priorities, and approach(es) as an instructor—that is to say, it's the key or legend to understanding all of the other materials (your syllabi, your student feedback, etc.) that come along with it. But it's also unique among all of the documents that you submit to hiring or promotion committees, insofar as it's a great opportunity to humanize yourself. While in your research statement you'll likely want to talk only about the successful aspects of your research record, and to stick to a thoroughly professional tone, in your teaching statement it's customary—even desirable—to be a little bit more honest and down-to-earth about your own growth as a teacher. A capacity for reflection, after all, is one of the best predictors of future growth and success for an instructor, and so it's a great idea to model that capacity in your statement. When you first began teaching, what misapprehension did you have about how students learn, or about how to motivate them? What experience(s) helped you become more astute in giving your students feedback on their work? How do you know that you are a better teacher today than when you started? And how do you bring your own personality—including, perhaps, your hobbies and/or unique life experiences—into your teaching to connect and build rapport with your students?

How to Think About Teaching Statements

It may be helpful to think about two things that effective teaching statements are, and two things they are not.

-

Two things they are:

-

A reflection of your relationship to your scholarly discipline(s). Scholarly fields are distinguished not only by what they study, how they study it, and what kinds of arguments and evidence they find persuasive, but also by how their members tend to believe a student most effectively advances from novice toward expert status—that is to say, by how they believe the curriculum is best organized, and by what kinds of experiences they think it's most important for students to have within that curriculum. How do you feel about those questions? What are the current conventions with which you most agree? Are there teaching practices in your field that you think are ripe for questioning or revision?

-

A window into the kind of relationship you seek to cultivate with your students. Effective teachers are invested in their students' success. But what does it mean to be "invested"? What are the things that you feel it is your job to supply, and how do you communicate to your students the things for which they are responsible? Is there a particular metaphor (or set of metaphors) that capture the relationship you seek to cultivate with your students? Are you a coach? An orchestra conductor? A gardener? A tour guide?

-

-

Two things they are not:

-

A teaching "philosophy" in an abstract or theoretical sense. Many ho-hum statements begin with a quotation from an authority figure in the history of education (e.g. Plato, John Dewey, … ) and never descend any further into the particulars of their writers' classrooms. While we understand the impulse, in fact, this is the opposite direction in which a teaching statement ought to go. What a reader wants to know by the time they put down your statement is what it is really like to be in your classroom. What are students doing? Why are they doing it? How do they experience your activities and assignments? How do you know your teaching is working? In an ideal world, universities would probably relabel "teaching philosophy statements" as "teaching practice statements."

-

A catalogue of all of your teaching experiences. Whether you detail your teaching experience in your CV, a one-page List of Teaching Experiences and Responsibilities, or both, you have plenty of other places to impress a committee with the range and extent of your experience. The value proposition of the teaching statement is what it can tell the reader about what you have learned from those teaching experiences, and how you hope to continue developing your practice. The vast majority of selection committees would prefer to elevate a thoughtful, analytical, reflective candidate with a modest quantity of experience over a candidate with a glut of experience they have not bothered to process very effectively.

-

How to Get Started on Your Own Statement

Here is one way that you might approach trying to draft your own teaching statement:

-

Start by "mapping" the curriculum of your department or program. With pen and paper, look at your department’s undergraduate curriculum as described on its website or in a student handbook. Try to create a visual representation of how a student moves through the major. How easy/hard is it to draw a coherent flowchart?

-

Where are there forking paths? Which courses serve as prerequisites for others? How much of each of your field's major approaches must a student encounter, and when?

-

Stepping back: What assumptions are being made about how students move from novice to expert in your field? What seem to be the key values and goals that (virtually) everyone in your field shares? And where are there opportunities for reframing or innovation?

-

-

Choose ca. three key values or priorities that you express in your own teaching. Ideally:

-

at least one of them connects to those key values and goals mentioned above.

-

at least one of them connects to a common challenge that instructors in your field often encounter.

-

at least one of them relates pretty directly to how you create equitable and inclusive environments.

-

-

Identify 1–2 vivid, concrete examples of how you express each of these values in your teaching. Remember to focus, as much as possible, on the student experience. See how many sentences you can flip from "I have students do X" to "Students have the opportunity to X." And remember as well to show what you have learned. What have you come to understand or appreciate better about how your students learn? What is hard for them? What seems intuitive?

-

If you're trying to figure how to incorporate these vivid examples into your statement in an economical way, we encourage you to practice narrating them with the help of Kurt Vonnegut's "story shapes"—who is the protagonist of your anecdote (you? your students? your academic field?), and what kind of challenge gives your anecdote its dramatic tension? What obstacle is the protagonist trying to overcome?

-

-

Revise. Almost all teaching statements incorporate comparisons into the first draft ("Some people say students are annoying, but I love them!"). We're willing to bet you can lose all of them in the second draft.

List of Positions and Responsibilities

Though your CV may already include a comprehensive list of your teaching positions—in which case you may want to include a copy of your full CV in your teaching portfolio—it’s a good idea to include a list of the teaching roles you’ve held, and a brief summary of the duties they entailed (e.g. “authored weekly problem sets,” “led weekly discussions,” “graded 200 pages of student work,” “designed lab protocols,” etc.), in your teaching portfolio.

Creating Your List

When drafting this list of positions and responsibilities, you may want to begin with a brief header paragraph that frames and summarizes your experience, such as how many classes you’ve taught, how many years you’ve been teaching, the variety of institutions in which you’ve taught, etc. You may want to consider whether there is some general description or clarification that would make all of your individual experiences more intelligible (e.g. explaining the meaning of a job title unique to your institution, or what kinds of teaching roles were available to you as a postdoc or early-career faculty member). Below is an example of how you might go on to describe your experiences:

Courses taught at Blank University

Course head, SAMPLE 101: Introduction to Sampleology - Fall 2021

Designed new introductory survey of Sampleology that enrolled 97 first- and second-year students. Authored and delivered 22 interactive lectures, and developed weekly problem sets, midterm exam, and final project for assessment. Supervised a staff of four Teaching Assistants. Received a score of 4.3/5 on student evaluations.

Courses taught at University of Gradschül

Teaching Assistant, SAMPLE 102: Advanced Sampleology (Prof. Complexity, course head) - Spring 2020

As Teaching Assistant, worked closely with the course head of a lecture course to schedule discussion sections, design the course Canvas site, and create the custom course reader. Resolved student requests for extensions and excused absences, and designed the midterm exam. Taught two weekly discussion sections (totaling 27 students) and led a staff workshop on grading sampleology papers.

Advising and Mentoring

Senior Thesis adviser, Department of Samples - AY 2019–2020

Supervised undergraduate writing a 75-page senior thesis on “The Banality of Lorem Ipsum Text.” Met with student weekly, offering tutorials on research methods and providing detailed feedback on chapter drafts. Participated in department committee evaluating all senior theses, voting on final honors recommendations. Student was awarded the department’s prize for Most Hypothetical Thesis.

Teaching Evaluations

Committees often request that candidates submit some or all of their student evaluations as part of their teaching portfolio; they may describe these evaluations euphemistically as “Evidence of Teaching Effectiveness.” The first thing to say about such requests is: don’t sweat the numbers! Search committees at other universities—even internal committees at your own institution—frankly don't have very strong intuitions about how to compare (say) a 4.0 in one course or semester to a 4.5 in another. Student evaluations are most useful to instructors themselves, as a way to glean additional insight into how students have been experiencing their teaching over the course of a semester. In isolation, they are not very useful to an evaluator standing outside of the course.

The second thing to say about student evaluations is that you should help the committee make sense of what they are seeing by compiling a ca. 1–2-page executive summary of the evaluations (i.e. rather than simply sending an undifferentiated mass of raw, uncollated data downloaded directly from your school's portal). You can then, at the end of this executive summary, provide a link to a DropBox or Google Folder where the committee can access the full, original data, should they so desire.

Displaying the Quantitative Data

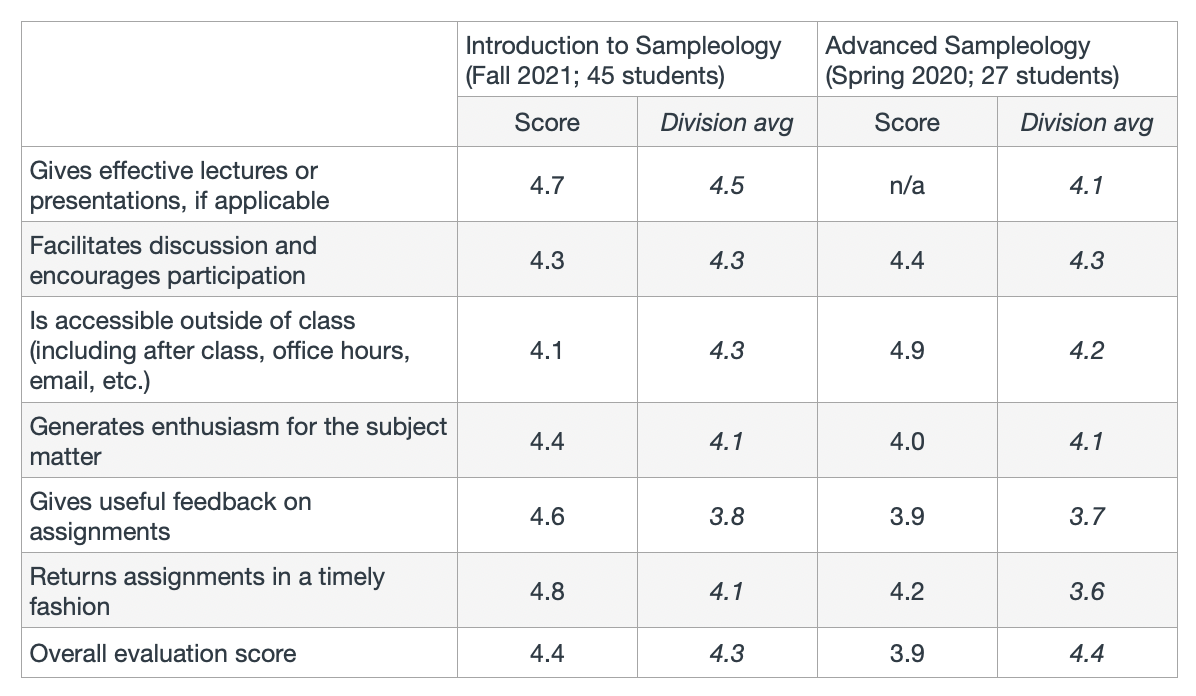

We recommend leading off your executive summary with a clean, tabular presentation summarizing the data, like so:

Quantitative Evaluations [Scale: 1 (unsatisfactory) to 5 (excellent)]

NB: Don’t forget to include some benchmarking (how many students completed the evaluations? What was the average score for the course or department or division?

NB: Don’t forget to include some benchmarking (how many students completed the evaluations? What was the average score for the course or department or division?

Displaying the Qualitative Data

You’ll also want to include a handful of representative qualitative feedback—not just, “___ was a great teacher!” Look for comments that, even if not 100% glowing, reveal that students understood the point of the course and the approach you were taking. For example:

Selected Qualitative Evaluations

“I wouldn’t have had the incredible experience I had in this class without _____. So friendly with students which helps to foster a sense of goodwill towards the subject - what a great ambassador for the department. So genuinely and unironically enthusiastic about the material that the sentiment is contagious. Very clear about expectations in papers which is both impressive, absolutely necessary, and dearly appreciated. Generous with both his time in office hours, his willingness to help in emails, and with his advice with how to approach the course format (lectures can be intimidating at first) and how to think about papers. He should be kept on as long as possible and given a higher teaching position if possible - he is a gem!!!!!!

“_____ always gave solid feedback on assignments, was very willing to look at drafts of my written work, graded in a timely manner, and was highly professional.”

“_____ was one of the highlights of taking this class; I am so glad to have met a kind and smart person like him. He always made me feel comfortable walking into class, and always had a smile/ helpful comment for me outside of the classroom.”

Sample Syllabi

The syllabus (or a collection of 2–3 syllabi) is one of the core components of any teaching portfolio. Alongside the Teaching Statement, the syllabus/syllabi arguably gives a committee the most insight as to a candidate's preferred approach to teaching students of different backgrounds and in different modalities.

Which Syllabi Should I Include?

When considering what kinds of syllabi to prepare and include in a teaching portfolio, we suggest, first of all, that you defer as much as possible to a search or review committee’s stated preferences. That is to say, if they ask for a syllabus for a specific course, make sure to give them a syllabus for that course!

In the absence of specific guidance from the search committee, we suggest preparing/submitting a syllabus for:

-

1 introductory lecture course, or its equivalent in your field or discipline, and

-

1 upper-division seminar on a more tailored topic, perhaps oriented towards demonstrating how you train students in research skills. This could double as a template for a graduate seminar, as needed.

How Detailed Should My Syllabi Be?

In the absence of explicit guidance, we suggest that you submit a full, (at least theoretically) "teachable" syllabus—that is to say, one that includes not only. description of the course, your goals, some assignments, and some readings, but a full schedule of the semester as well as all of the "course policies" language you would be likely to include on a real student-facing document. While you may think of this language as mere "boilerplate"—and may have to omit it if the committee gives you a very constrained length within which to work—we think that the way instructors talk to students about expectations, absences, academic honesty, etc. is often actually the most revealing portion of a syllabus.

Reference(s) that can Speak to your Teaching

Ideally, if you're on the job market and are asked to submit references, your three primary referees already are able to speak to your teaching experience. If so, feel free to disregard the advice below.

If, however, your three most compelling references are not able to speak in great detail about your teaching experience (e.g. you’ve never had the chance to teach with or for your advisor or mentor), you might solicit an additional letter from someone like a course head, department chair, Director of Undergraduate Studies, or Language Program Director with whom you’ve worked closely and include it in your teaching portfolio.

What About Letters from Students?

We generally recommend against including references from students. Not only do they raise the specter of uneven power dynamics, they are also generally not as insightful or helpful as the other materials in your dossier.