Program History

As an academic discipline, American Studies was born at Harvard University shortly before World World II.

In the 1940s, when the United States became the preeminent world power, the republic begged to be understood in a special way. Neither "exceptionalist" smugness nor "Old World" condescension alone would do.

Drawing in particular upon the established disciplines of English and history, the new field took the social institutions and cultural values of this newly powerful nation to be worthy of explanation and analysis in their own right. For more than seven decades, that rationale has continued to embody American sStudies.

Founded in 1948, Brandeis University itself emerged even as American studies was becoming a discipline of its own. But in the first decade of the university, no separate departments were deemed necessary. As a program, American studies soon emerged, and finally became a department in 1970.

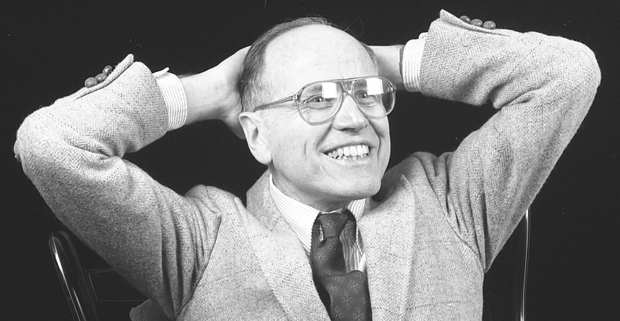

The Influence of Max Lerner

Its key figure was Max Lerner, a public intellectual who taught at Brandeis from 1949-73. The lecture course that Lerner offered was once required of all sophomores at the university and was devoted to "America as a civilization." His magnum opus of that title, published in 1957, is considered by many to be an update of Alexis de Tocqueville's classic "Democracy in America" as an inquiry into the national character.

Its key figure was Max Lerner, a public intellectual who taught at Brandeis from 1949-73. The lecture course that Lerner offered was once required of all sophomores at the university and was devoted to "America as a civilization." His magnum opus of that title, published in 1957, is considered by many to be an update of Alexis de Tocqueville's classic "Democracy in America" as an inquiry into the national character.

Lerner was a liberal magazine editor, a columnist and a polemicist on behalf of progressive causes. He was also a scholar, and his two vocations set the tone for the early phase of American studies at Brandeis.

Fuchs Fused Scholarship, Political Activism

Political activism and scholarship also marked the career of Lawrence H. Fuchs, who taught at Brandeis from 1952 until his retirement a half century later. Fuchs wrote speeches on world peace, self-determination and minority relations for then-U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy. He became the first director of the Peace Corps in the Philippines and, under President Jimmy Carter, served as executive director of the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy.

Political activism and scholarship also marked the career of Lawrence H. Fuchs, who taught at Brandeis from 1952 until his retirement a half century later. Fuchs wrote speeches on world peace, self-determination and minority relations for then-U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy. He became the first director of the Peace Corps in the Philippines and, under President Jimmy Carter, served as executive director of the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy.

Fuchs' first book, "The Political Behavior of American Jews" (1956), remains definitive. His most ambitious work, "The American Kaleidoscope: Race, Ethnicity and the Civic Culture" (1990), won the John Hope Franklin Prize of the American Studies Association for the best book in the field of American studies. It also was given the Saloutos Prize in immigration history.

Fuchs was the key figure in hiring colleagues who also combined a flair for teaching with a proclivity for political activism. Their interests tilted the orientation of the department heavily in the direction of social science, rather than strictly the humanities, which at that time was unusual in the field of American studies.

Other Early Program Pioneers

Pauli Murray was a professor, civil rights activist, pioneering feminist, poet, attorney and Episcopal priest whose amazingly varied career is recounted in her autobiography, "Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage" (1987). In early 21st-century America, Murray's life and career have garnered the attention of a new generation of activists, as evidenced by a profile of her that the New Yorker ran in 2018 and a 2021 documentary by Betsy West.

William Goldsmith had been a labor organizer on behalf of the Textile Workers Union of America before joining the department of politics and, subsequently, the American studies department.

Jacob Cohen joined the history department in 1961 and took a leave of absence from the university from 1964-68 — among the most tumultuous years of the civil rights movement — to serve on the staff of the Congress of Racial Equality. When he returned, he joined the American Studies department.

Along with John Matthews, who joined American Studies from the Theater Arts department, the team of Murray, Goldsmith, Cohen and Fuchs formed a department that worked (and continues to work) exclusively with undergraduate students and introduced courses into the Brandeis curriculum that would later grow into entire other programs and even departments, such as African and Afro-American Studies, Women's and Gender Studies and Environmental Studies.

In recent years, the American Studies program has hosted conferences to mark the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer and the university's acquisition of Lenny Bruce's personal papers. Freedom Summer was a campaign launched in June 1964 to register African American voters in Mississippi; civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were famously murdered during that campaign. Bruce was a comedian and satirist whose routines bumped up against the social and legal mores of America in the 1950s and '60s. He was arrested for "obscenity" on a number of occasions, and his legal challenges to those charges made him a pioneer for free expression and the rights codified in the First Amendment.

Scholarship Comes to the Fore

Scholarly distinction characterizes Brandeis' American Sstudies program. Professor Brian Donahue's "The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord" (2004) won the Marsh Prize from the American Society for Environmental History, the Saloutos Prize from the Agricultural History Society and the Best Book Prize from the New England Historical Association. Professor Thomas Doherty's "Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930-34" (1999) won the Theater Library Association award for excellence in writing on film and broadcasting.

Additionally, Emerita Professor Eileen McNamara was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Commentary in 1997 for her work as a columnist at the Boston Globe.

Three members of the department have won one of the university's highest honors, the Louis D. Brandeis Prize for Excellence in Teaching: Stephen Whitfield in 1993; Mary Davis (also a member of the Legal Studies program), in 2001 and Eileen McNamara (Journalism) in 2011.

In 2010, Richard Gaskins won the Lerman-Neubauer ’69 Prize for Excellence in Teaching and Mentoring, and Maura Jane Farrelly won the Michael L. Walzer Award for Teaching.